Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – April 29-30, 2017 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

In the absence of exchange rate flexibility, the Eurozone member states have to use painful internal devaluation designed to deflate nominal wages and prices in order to facilitate increased external competitiveness. If wages and prices fall at the same rate, then, for the logic to follow, labour productivity has to rise and employment has to fall.

The answer is False.

The correct answer is that if wages and prices fall at the same rate, then labour productivity has to rise but what happens to employment is irrelevant.

The EMU countries cannot improve their international competitiveness by exchange rate depreciation, which is the option always available to a fully sovereign nation issuing its own currency and floating it in foreign exchange markets.

Thus, to improve their international competitiveness, the EMU countries have to engage in “internal devaluation” which means they have to cut real unit labour costs – which are the real cost of producing goods and services. Governments setting out on this policy path have to engineer cuts in the wage and price levels (the latter following the former as unit costs fall).

But the question demonstrates that it takes more than just a nominal deflation. The strategy hinges on whether you can also engineer productivity growth (typically).

Some explanatory notes to accompany the analysis that follows:

- Employment is measured in persons (averaged over the period).

- Labour productivity is the units of output per person employment per period.

- The wage and price level are in nominal units; the real wage is the wage level divided by the price level and tells us the real purchasing power of that nominal wage level.

- The wage bill is employment times the wage level and is the total labour costs in production for each period.

- Real GDP is thus employment times labour productivity and represents a flow of actual output per period; Nominal GDP is Real GDP at market value – that is, multiplied by the price level. So real GDP can grow while nominal GDP can fall if the price level is deflating and productivity growth and/or employment growth is positive.

- The wage share is the share of total wages in nominal GDP and is thus a guide to the distribution of national income between wages and profits.

- Unit labour costs are in nominal terms and are calculated as total labour costs divided by nominal GDP. So they tell you what each unit of output is costing in labour outlays; Real unit labour costs just divide this by the price level to give a real measure of what each unit of output is costing. RULC is also the ratio of the real wage to labour productivity and through algebra I would be able to show you (trust me) that it is equivalent to the Wage share measure (although I have expressed the latter in percentage terms and left the RULC measure in raw units).

The following table models the constant and growing productivity cases but holds employment constant for five periods. We assume that the nominal wage and the price level deflate by 10 per cent per period over Period 2 to 5. In the productivity growth case, we assume it grows by 10 per cent per period over Period 2 to 5.

It is quite clear that under the assumptions employed, RULC cannot fall without productivity growth. The only other way to accomplish this is to ensure that nominal wages fall faster than the price level falls. In the historical debate, this was a major contention between Keynes and Pigou (an economist in the neo-classical tradition who best represented the so-called “British Treasury View” in the 1930s. The Treasury View thought the cure to the Great Depression was to cut the real wage because according to their erroneous logic, unemployment could only occur if the real wage was too high.

Keynes argued that if you tried to cut nominal wages as a way of cutting the real wage (given there is no such thing as a real wage that policy can directly manipulate), firms will be forced by competition to cut prices to because unit labour costs would be lower. He hypothesised that there is no reason not to believe that the rate of deflation in nominal wage and price level would be similar and so the real wage would be constant over the period of the deflation. So that is the operating assumption here.

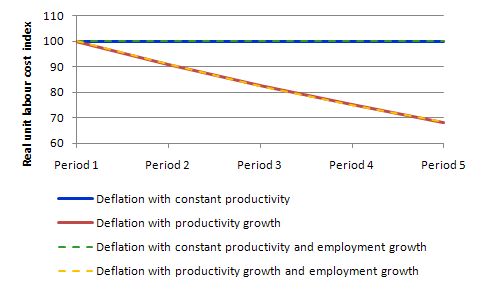

The following table models the constant and growing productivity cases as above but allows employment to grow by 10 per cent per period. All four scenarios in the Table are them modelled in the following graph with the Real Unit Labour Costs converted into index number form equal to 100 in Period 1. As you can see what happens to employment makes no difference at all.

I could have also modelled employment falling with the same results.

The following graph shows the four scenarios shown in the last two tables. I have dashed some scenarios to make the lines visible (given that Case A and Case C) are equivalent as are Case B and Case D. What you learn is that if wages and prices fall at the same rate and labour productivity does not rise there can be no reduction in unit or real unit labour costs.

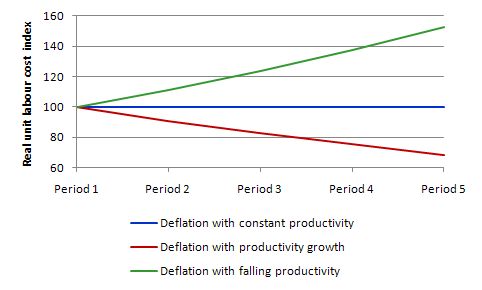

So the internal devaluation strategy relies heavily on productivity growth occurring. The literature on organisational psychology and industrial relations is replete of examples where worker morale is an important ingredient in accomplishing productivity growth. In a climate of austerity characteristic of an internal devaluation strategy it is highly likely that productivity will not grow and may even fall over time. Then the internal devaluation strategy is useless.

This graph compares the two scenarios in the first Table with the more realistic one that labour productivity actually falls as the government ravages the economy in pursuit of its internal devaluation. As you can see real unit labour costs rise as labour productivity falls and the economy’s competitiveness (given the exchange rate is fixed) falls.

Of-course, this “supply-side” scenario does not take into account the overwhelming reality that for an economy to realise this level of output over an extended period aggregate demand would have to be supportive. The internal devaluation strategy relies heavily on the external sector providing the demand impetus.

Given that Eurozone trade is heavily internal, it seems far fetched to assume that the trade impact arising from any successful internal devaluation will be sufficient to overcome the devastating domestic contraction in demand that will almost certainly occur. This is why commentators are calling for a domestic expansion in Germany to boost aggregate demand throughout the EMU, given the dominance of the German economy in the overall European trade.

That is clearly unlikely to happen given Germany has been engaged in a lengthy process of internal devaluation itself and the Government is resistant to any stimulus packages that might improve things within Germany and beyond via the trade impacts.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

- EMU posturing provides no durable solution

- Protect your workers for the sake of the nation

- The bullies and the bullied

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

Question 2:

To ensure that the financial system is stable, the central bank has to allow movements in the money supply to be driven by the movements in the monetary base.

The answer is False.

The question relates to the money multiplier. Mainstream macroeconomics textbooks are incorrect when they discuss the credit-creation capacity of commercial banks. The concept of the money multiplier is at the centre of this analysis and posits that the multiplier m transmits changes in the so-called monetary base (MB) (the sum of bank reserves and currency at issue) into changes in the money supply (M). The chapters on money usually present some arcane algebra which is deliberately designed to impart a sense of gravitas or authority to the students who then mindlessly ape what is in the textbook.

In their undergraduate courses (introductory and intermediate macroeconomics; money and banking; monetary economics etc) the money multiplier is usually expressed as the inverse of the required reserve ratio plus some other novelties relating to preferences for cash versus deposits by the public.

Accordingly, the students learn that if the central bank told private banks that they had to keep 10 per cent of total deposits as reserves then the required reserve ratio (RRR) would be 0.10 and m would equal 1/0.10 = 10. More complicated formulae are derived when you consider that people also will want to hold some of their deposits as cash. But these complications do not add anything to the story.

The formula for the determination of the money supply is: M = m x MB. So if a $1 is newly deposited in a bank, the money supply will rise (be multiplied) by $10 (if the RRR = 0.10). The way this multiplier is alleged to work is explained as follows (assuming the bank is required to hold 10 per cent of all deposits as reserves):

- A person deposits say $100 in a bank.

- To make money, the bank then loans the remaining $90 to a customer.

- They spend the money and the recipient of the funds deposits it with their bank.

- That bank then lends 0.9 times $90 = $81 (keeping 0.10 in reserve as required).

- And so on until the loans become so small that they dissolve to zero

None of this is remotely accurate in terms of depicting how the banks make loans. It is an important device for the mainstream because it implies that banks take deposits to get funds which they can then on-lend. But prudential regulations require they keep a little in reserve. So we get this credit creation process ballooning out due to the fractional reserve requirements.

The money multiplier myth also leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted hometo the “government”. This leads to claims that if the government runs a fiscal deficit then it has to issue bonds to avoid causing hyperinflation. Nothing could be further from the truth.

That is nothing like the way the banking system operates in the real world. The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates.

First, the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply in a modern monetary system. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank. The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

Second, this suggests that the decisions by banks to lend may be influenced by the price of reserves rather than whether they have sufficient reserves. They can always get the reserves that are required at any point in time at a price, which may be prohibitive.

Third, the money multiplier story has the central bank manipulating the money supply via open market operations. So they would argue that the central bank might buy bonds to the public to increase the money base and then allow the fractional reserve system to expand the money supply. But a moment’s thought will lead you to conclude this would be futile unless (as in Question 3 a support rate on excess reserves equal to the current policy rate was being paid).

Why? The open market purchase would increase bank reserves and the commercial banks, in lieu of any market return on the overnight funds, would try to place them in the interbank market. Of-course, any transactions at this level (they are horizontal) net to zero so all that happens is that the excess reserve position of the system is shuffled between banks. But in the process the interbank return would start to fall and if the process was left to resolve, the overnight rate would fall to zero and the central bank would lose control of its monetary policy position (unless it was targetting a zero interest rate).

In lieu of a support rate equal to the target rate, the central bank would have to sell bonds to drain the excess reserves. The same futility would occur if the central bank attempted to reduce the money supply by instigating an open market sale of bonds.

In all cases, the central bank cannot influence the money supply in this way.

Fourth, given that the central bank adds reserves on demand to maintain financial stability and this process is driven by changes in the money supply as banks make loans which create deposits.

So the operational reality is that the dynamics of the monetary base (MB) are driven by the changes in the money supply which is exactly the reverse of the causality presented by the monetary multiplier.

So in fact we might write MB = M/m.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

- Teaching macroeconomics students the facts

- Lost in a macroeconomics textbook again

- Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained

- Oh no … Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- 100-percent reserve banking and state banks

- Money multiplier and other myths

Question 3:

The cost of spending by a sovereign government increases when the bond markets push yields on new government bond issues up.

The answer is False.

Note we are excluding non-sovereign governments such as the member states in the EMU which use a foreign currency.

For a sovereign government that issues its own currency there is no binding revenue constraint on government spending. The interest servicing payments come from the same source as all government spending – its infinite (minus one cent!) capacity to issue fiat currency. There is no “cost” – in real terms to the government doing this.

The concept of more or less expensive is therefore inapplicable to government spending.

The cost of government spending is the real resources that are deployed in the production of the goods and services being purchased rather than the fiscal transaction entry in the Treasury books.

Rising bond yields do not measure these opportunity costs.

In macroeconomics, we summarise the plethora of public debt instruments with the concept of a bond. The standard bond has a face value – say $A1000 and a coupon rate – say 5 per cent and a maturity – say 10 years. This means that the bond holder will will get $50 dollar per annum (interest) for 10 years and when the maturity is reached they would get $1000 back.

Bonds are issued by government into the primary market, which is simply the institutional machinery via which the government sells debt to “raise funds”. In a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates it is clear the government does not have to finance its spending so the the institutional machinery is voluntary and reflects the prevailing neo-liberal ideology – which emphasises a fear of fiscal excesses rather than any intrinsic need.

Once bonds are issued they are traded in the secondary market between interested parties. Clearly secondary market trading has no impact at all on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders. In the context of public debt issuance – the transactions in the primary market are vertical (net financial assets are created or destroyed) and the secondary market transactions are all horizontal (no new financial assets are created). Please read my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

Further, most primary market issuance is now done via auction. Accordingly, the government would determine the maturity of the bond (how long the bond would exist for), the coupon rate (the interest return on the bond) and the volume (how many bonds) being specified.

The issue would then be put out for tender and the market then would determine the final price of the bonds issued. Imagine a $1000 bond had a coupon of 5 per cent, meaning that you would get $50 dollar per annum until the bond matured at which time you would get $1000 back.

Imagine that the market wanted a yield of 6 per cent to accommodate risk expectations (inflation or something else). So for them the bond is unattractive and they would avoid it under the tap system. But under the tender or auction system they would put in a purchase bid lower than the $1000 to ensure they get the 6 per cent return they sought.

The mathematical formulae to compute the desired (lower) price is quite tricky and you can look it up in a finance book.

The general rule for fixed-income bonds is that when the prices rise, the yield falls and vice versa. Thus, the price of a bond can change in the market place according to interest rate fluctuations.

When interest rates rise, the price of previously issued bonds fall because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering a higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increase, becoming more attractive as newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

Further, rising yields may indicate a rising sense of risk (mostly from future inflation although sovereign credit ratings will influence this). But they may also indicated a recovering economy where people are more confidence investing in commercial paper (for higher returns) and so they demand less of the “risk free” government paper.

So you see how an event (yield rises) that signifies growing confidence in the real economy is reinterpreted (and trumpeted) by the conservatives to signal something bad (crowding out). In this case, the reason long-term yields would be rising is because investors were diversifying their portfolios and moving back into private financial assets. The yield reflects the last auction bid in the bond issue. So if diversification is occurring reflecting confidence and the demand for public debt weakens and yields rise this has nothing at all to do with a declining pool of funds being soaked up by the binging government!

But all of that has nothing to do with the real resource costs embodied in goods and services that governments purchase.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Is the UK still “monetary sovereign”? It has its own currency, but it signed the Lisbon Treaty which restricts it right to be unrestricted in spending. I believe it can deficit spend as long as it sells gilts to match. That sounds simple to work around.

Your question 3.

Thanks

John Doyle.

It depends what you mean by “monetarily sovereign” I suppose. Yes it still issues its own currency, but my understanding is paragraph 1 prohibits overdraft facilities for member states at either the ECB or their national central banks. As that’s how money creation actually works (though the article misunderstands the whole money creation process anyway) it effectively could be argued that a member country has given up its monetary sovereignty by signing the Treaty because it no longer has the mechanism for creating money.

The question of deficits is covered by the Stability and Growth Pact that limits signatories to a deficit of 3% of GDP. Article 123, paragraph 2 allows governments to borrow from “publicly owned credit institutions” – ie commercial banks – so it can deficit spend by borrowing from such institutions but still only within 3% of GDP. There is a mechanism through which a member state can apply to the Commission for a temporary increase in this limit.

As these “publically owned credit institutions” stand to profit from this arrangement, I feel pretty sure that the government will agree to adhere to that requirement in their exit negotiations. Brexit is highly unlikely to mean Brexit, I’m afraid, especially as our “strong and stable” leaders don’t understand how the monetary system works.

Nigel,

‘so it can deficit spend by borrowing from such institutions but still only within 3% of GDP. ‘ Spain France and Belgium are all over the 3% mark at present with Spain at 4.42% -Bill has written about Spain being given special ‘dispensation’ in order to prop up the Conservative administration.

The debt to GDP ratio is supposedly limited at 60% -the debt Ranges fro 9.5 (Estonia) to 170% (Greece) according to 2016 figures.

It’s a completely absurd set up. The government created the pound, yet it has to borrow its own money?!

How it ever agreed to that is a sure sign their understanding of economics etc is woeful.

Re Simon, I read recently the EU has blown all those checks out the window as there are noises about a Trillion euro bailout for paying down all those unpayable debts in Greece etc? Is that true?