When I was just coming into adulthood (1972), the - Club of Rome - published…

Productivity growth is not the only source of increases in material well-being for the majority

One of the issues that emerges when one is studying undergraduate macroeconomics is that there is a curious disregard for the role that income and wealth distribution play in determining the aggregate outcomes, that are at the centre of the study. Most students in my cohort didn’t think about that and the curriculum certainly didn’t encourage such digressions. For me, a student of Marx basically, I was extremely interested in the topic and read a lot outside the standard curriculum, which took me into the work of Sidney Weintraub and others, for example, who demonstrated how aggregate spending was not just influenced by income but also how that income was distributed. I have been thinking about this issue in relation to the way the Australian debate at present is being dominated by the productivity question and the imperative for a degrowth strategy to emerge. This thinking is also in relation to the Federal government’s – Economic Reform Roundtable – which they are running in Canberra this week, led by the Treasurer. The overarching theme is ‘Making our economy more productive’ so we can grow faster. Exactly the opposite of a discussion about degrowth.

With the ‘Economic Reform Roundtable’ starting tomorrow the talk in the media etc is ‘growth, growth, growth’.

People typically conflate more output growth and higher productivity growth, even though the two concepts are quite distinct.

But the motivation for increasing productivity growth is to push the overall GDP growth rate up.

The mainstream economists that are getting a lot of media attention in the lead up to the event are claiming that the only way our material living standards can increase is through productivity growth which will allow GDP growth to accelerate.

And, of course, they are joined by the throng of corporate shills who demand less regulation to ‘speed things up’, which is code for making jobs less secure and allowing things like construction codes to be watered down.

The problem is clear – there is no recognition at all in the public debate surrounding the Roundtable of the fact that Australia’s – Ecological footprint – is well above the global average of 1.7, which in itself is unsustainable.

In per capita terms, Australia’s 2024 footprint was 6.1 (within the top 10), which means that the imperative is not to find how to grow faster, but, rather, how we can still function with a degrowth strategy.

Which leads me to think about income and wealth distributions, another issue that won’t get a look in at this week’s event in Canberra.

When we talk about improving material living standards, the usual mainstream solution is that productivity growth – that is, growth in output per unit of input – must rise.

This means that a given set of productive resources is able to produce more and that increased real demands on the income distribution by the owners of those productive resources can be accommodated without inflationary pressures.

And as it stands, that proposition is correct.

The more we can produce with less the more is available for distribution to each person in the society.

Note also that I am not wanting to have a discussion here about what constitutes productivity growth – given I have a much broader view of the concept than the mainstream position that eschews a lot of social activity as being a waste of productive time.

So I am just accepting the standard approach here.

However, that proposition doesn’t really factor in the biosphere, unless the claims on that resource are explicitly included in the output and input estimates.

And, of course, the mainstream approach never really includes the negative consequences for our biosphere of expanding output growth, which means the figures they chase in terms of productivity growth are biased towards non-sustainability.

But there is another way that material living standards for the majority of people can be improved while pursuing a degrowth strategy.

And that involves policy shifts oriented towards changing the income and wealth distributions, which are linked.

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data on – Household Income and Wealth, Australia – was released on April 28, 2022 and is based on information gathered in the Survey of Income and Housing 2019-20.

So it is now somewhat dated but the situation will not have changed that much as time has elapsed.

The income distribution in Australia has, in fact, been very stable over the decade to 2019-20.

The quintile shares have barely changed, the lowest 20 per cent had 7.4 per cent of total disposable income, the second 20 per cent had 12.6 per cent, the third quintile had 17.2 per cent, the fourth quintile had 23 per cent and the top 20 per cent had 39.8 per cent.

That data alone tells us how unequal the distribution is even if the level of inequality is mostly unchanged.

However, over the decade to 2019-20 there was a slight deterioration in the Gini coefficient for disposable income which means the distribution became somewhat more unequal, but the shift is very marginal, suggesting there is some stability in the indicator.

In 2009-10, the P90/P10 ratio was 4.35, which means that those at the 90th percentile of the income distribution had just over 4.35 times the weekly income of households at the 10th percentile.

By 2019-20, that ratio was 4.0, a slight decline but still indicative of a huge disparity in weekly nominal outcomes.

I haven’t got time today to model what changes would keep the ‘All households’ average constant yet redistribute significant income to the lower quintiles to reduce ratios like that.

But given the disparity that exists there is massive scope to reduce the disposable income at the top end and increase the disposable income for the low-paid without the economy generating any more overall national income.

Such a strategy would dramatically increase the material well-being of the larger proportion of citizens while a degrowth strategy could be pursued.

So it is not true that we need more output growth via productivity growth to improve material living standards.

The ABS also publishes “financial stress indicators” which are computed based on responses to the Survey.

The list of selected indicators is:

Unable to raise $2,000 in a week for something important

Unable to raise $500 in a week for something important

Spend more money than received

Could not pay electricity, gas or telephone bill on time

Could not pay mortgage or rent payments on time

Could not pay car registration or insurance on time

Could not pay home or contents insurances on time

Could not make minimum payment on credit card on time

Pawned or sold something

Went without meals

Went without dental treatment

Were unable to heat or cool home

Sought financial assistance from friends or family

Sought assistance from welfare/community organisations

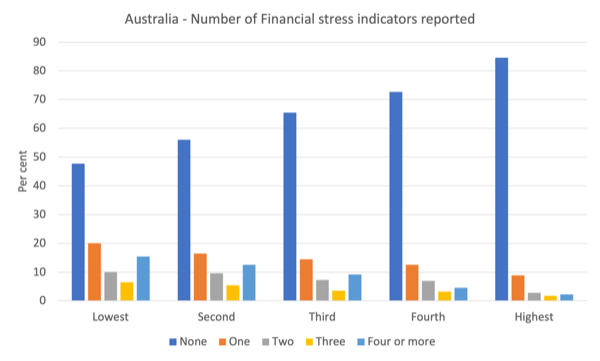

In 2019-20, the distributional biases are clear for this indicator.

The following graph shows the ‘number of financial stress indicators’ reported for each of the quintiles.

For the lowest quintile, the highest six indicators were:

1. Unable to raise $2,000 in a week for something important: 32.8 per cent

2. Unable to raise $500 in a week for something important: 16.1 per cent

3. Spend more money than received: 15.2 per cent

4. Could not pay electricity, gas or telephone bill on time: 15.0 per cent

5. Sought financial assistance from friends or family: 14.4 per cent

6. Went without dental treatment: 13.4 per cent

20.3 per cent of households in the lowest quintile said they were ‘Unable to raise $500 in a week for something important’ – which means they are very exposed to the usual calamities that arise that need immediate attention.

The wealth distribution is much more unequal than that the income distribution, in part, because the fiscal system helps reduce the ‘market-based’ income outcomes via taxation and transfers, whereas the system reinforces the wealth disparities by giving massive concessions, for example, to property investors (the so-called negative gearing policy).

Further, the dominance of monetary policy as the principle counterstabilisation macroeconomic policy typically works for the rich.

The recent interest rate hikes (up to November 2022) redistributed massive amounts of income from low-income mortgage holders into the hands of those with financial assets (wealth), which allowed the latter cohort to expand their wealth holdings at the expense of the former.

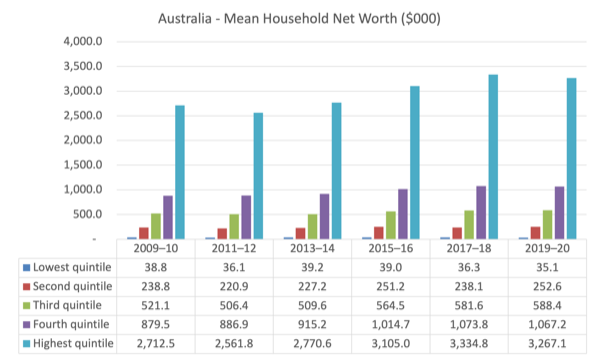

In terms of the Wealth distribution, the following graphs tell the story.

First, the ‘Mean household net worth between 2009-10 and 2019-20’ are shown by quintile.

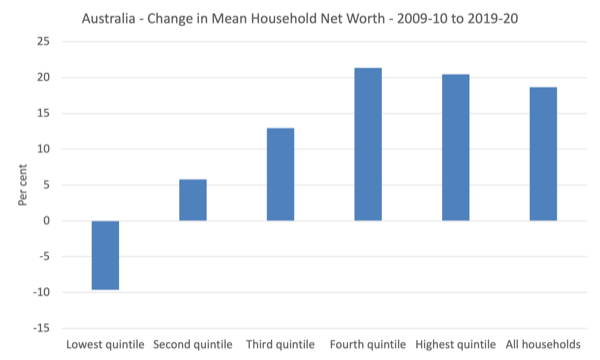

Second, the percentage change in mean net worth over that period is shown in the next graph.

The lowest quintile has gone backwards while the top two quintiles have moved further ahead.

In 2009-10, the P90/P10 ratio was 49.16, which means that those at the 90th percentile of the wealth distribution had just over 49 times the net worth of households at the 10th percentile.

By 2019-20, that ratio had grown to 61.13, which reveals a massive wealth disparity and a huge capacity to redistribute wealth to improve the material fortunes of those at the bottom end of the distribution.

Is this a tax the rich argument?

It is but with a nuance.

And to be clear once again, we are not advocating taxing the rich so that the government can gain funds to spend on low-income families.

Clearly, that is what will be the result.

The government could easily boost the weekly incomes of the low-income families without doing anything to the higher-income families by simply introducing some cash stipend or other interventions, such as free child care etc.

But the point is that it must achieve more equity without adding any extra spending pressure to the economy if it wanted to pursue a degrowth strategy.

In that case it has to take purchasing power off the higher income earners and transfer it to the lower income earners understanding that their spending propensities (for each extra dollar) are different.

So we need to tax the rich to deprive them of spending capacity to create the resource space for the lower income cohorts to enjoy a higher material standard of living through their extra spending.

There are other reasons to tax the rich – for example, to reduce their capacity to influence the political process and control the media.

But today I consider a quite separate reason.

Conclusion

While productivity growth is clearly a way to expand output and national income for a given set of productive resources, blindly pursuing real GDP growth will worsen our already unsustainable demands on the biosphere.

A degrowth-consistent strategy to improve material living standards must include significant redistribution of wealth and income, which will make it even more difficult to achieve, given all the other aspects that need to be put in place as well.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“So we need to tax the rich to deprive them of spending capacity to create the resource space for the lower income cohorts to enjoy a higher material standard of living through their extra spending.”

The trouble is it is remarkably difficult to achieve that outcome.

The rich have power in the current institutional arrangements and they will simply markup the charge and pass it on like any other business cost. That will increases prices throughout the structure, all of which will be validated by providing extra government income to other people, as well as extra government income via the effect of index-linking clauses in government contracts, and of course the usual interest rate mechanism responding to the ‘inflation’.

The economic incidence of taxation is unlikely to be the same as the legal incidence of taxation. There is always a push back within the pricing structure. Hence we get ‘patriotic millionaires’ demanding tax rises, so they can gather value-signalling brownie points, safe in the knowledge that their net-trouser won’t get touched at all.

Lower income cohorts need a material increase in their bargaining power if they are to resist having to stand the economic loss of tax rises, regardless of where those taxes are legally applied in the currency area. It’s that increase in bargaining power where the best chance for effective redistribution lies.

Hi Bill. I think you intended to write ‘without’ rather than ‘with’ in the two paras: ‘But given the disparity that exists …with the economy …’ and ‘But the point is that must achieve more equity with adding any extra spending pressure to the economy if it wanted to pursue a degrowth strategy.’

Anyone wanting a wider perspective on wealth and sustainability etc., might wish to digress in turning to Frederick Soddy for an early ‘heterodox’ discussion of the limits of growth economics from a scientific perspective, and hence degrowth.

Soddy also was the clear foreunner of Galbraith’s Entropy Economics, as well as providing a fairly blistering critique of much, if not all, classical economic theory in “Wealth, Virtual Wealth, and Debt”.

Even writing just before the 1926 crash he wrote, not entirely rhetorically :-

” Is our civilisation to end in breeding the Robot and the rentier, and to go down under class conflicts at home and fratricidal wars abroad ? “

Regarding wealth distribution- I’m in favour of building more,lots more so that housing supply significantly exceeds demand.This would lower housing costs for everyone and improve financial stability for the poorest; enable the bottom half to save.This would also adversely affect the wealth of those who own Property.

Really its an indirect wealth tax which improves living standards for the bottom half of society.

Jim Chalmers (recommended reading for the Ministry), Andrew Leigh, Danielle “the growth of regulatory burden” Wood of the Productivity Commission, the BCA and all the rest are besotted by Ezra Klein’s Abundance to give them cover. They’re all singing from the same songsheet. Keep up everyone – Treasurer reads a book and finds productivity solution then calls a Roundtable!

The employers, their captive politicians and corporate media propagandists all talk productivity but never distribution. But then, of course, that trickles down from profits, doesn’t it? Somewhat like never talking of money, per se, or to quote Soddy “Politicians of all parties…seem anxious to discus anything and everything rather than money.”. He could have also included income and wealth distribution.

There are folks at the bottom of the financial heap whose lives could be virtually instantly improved by being raised above the poverty line. Politicians, while being theologically inclined, fear the backlash from their masters if they show their power via public spending to raise people up (how quick was Morrison to ‘snapback’ the increase in JobSeeker early in the pandemic). It may give the hoi polloi bolshie ideas. Politicians can always spend up big when it comes to war toys, that most would like to see remain unused, but little spending for an ongoing improvement in the well being of the citizens.

The Roundtable should have been an opportunity to plan to reduce working hours, stomp on price gouging and ensure an improving equity in distribution. That sounds like real work so they’ll go for the usual neoliberal solution spelled out in Abundance.

Australia no longer produces much “stuff” but is mostly a services based society today, apart from the dig it up and ship it out of mining and its associated methane gas extraction give-away activities. Both with minimum value add and using skeleton employment. Services, being a personal exertion activity, are limited by us as being human with the serfs, sorry workers, only having a fixed and limited time in a day to be usefully productive; many in David Graeber’s bullshit jobs. Taylorism isn’t going to do it for services past a human limitation point in the process after which breakdown and collapse of a workforce is in prospect. Well, we can have autonomous tech to replace those difficult to deal with humans and that is the path that urgers of western financialised capitalist economies are on. On top of all that, services, in a capitalist economy, are essentially parasitically extractive of the productive economy while capital fools the dim politicians, and their fellow travelers, supported by finance, into including profits gleaned by finance as adding to the sacred GDP metric in various jurisdictions (USA being most prominent). Dare not see finance as an overhead to be borne by production. Having elevated the FIRE sector above a mere utility, its beneficiaries aren’t going to acquiesce in reversing their position.

Continuing the race to the bottom and failing to transform income and wealth distribution to improve the lives of the many sounds like a recipe for disaster to me. Tack on unaffordable housing and all they want to do is distract us with is a gabfest on unexamined bases for productivity? Doing nothing or the wrong thing to give an appearance of doing something. Very Albanese 2.0.

There are reasons to push back against the idea that housing prices are high because of insufficient supply. In his blog _Economics from the Top Down_, Blair Fix published a couple of articles last year:

* _The American Housing Crisis: A Theft, Not a Shortage_

and before tat,

* _From Commodity to Asset: The Truth Behind Rising House Prices_

The core of “A Theft” is the erosion of wages in America over the last 50 years. The core of “Commodity to Asset” are the structural reasons (to my dismay) that drove the shift in basis for house prices.

The analysis is based on the American situation, so it might have to be altered to fit Australia, or it perhaps might not fit Australia at all.

Bill, thanks for the effort in educating us.

Two questions:

1 – Have you been reading the Guardian opinion pieces in the lead-up to the roundtable?

I have been, and have not been surprised, but have been appalled at how mediocre they have been and the absence of the biosphere in 99.99% of the verbiage.

2 – I am serious here: why the hell wasn’t a seat reserved for your goodself.

Having just completed Andreas Malm and Wim Carton, Overshoot: How the World Surrendered to Climate Breakdown (Verso, 2024) I am wondering if there is not another reason to tax the rich: to constrain the amount of money they can spend on destroying the Earth?

A music recommendation: https://sandshypno.bandcamp.com/track/sands

best wishes

Growth is required in the mainstream paradigm because only a “bigger pie” can address economic scarcity (poverty) given that Pareto optimality is the assumed “social welfare function” (SWF).

Growth is required because redistribution (“slicing the pie differently”) would impinge on free markets through taxation and/or regulation. Any impingement on free markets would inhibit achievement of Pareto optimality and thereby reduce social welfare under the mainstream model.

Given the chosen social welfare function of Pareto optimality (“that’s the best we can do”), and that Pareto optimality is seen to be achieved through free markets (minimizing taxation and regulation), redistribution is off-limits: The only answer to economic scarcity is growth.

Change the social welfare function to, say, sum of utilities (Harsanyi) or maximin (Rawls), and redistribution becomes a viable alternative.

The difficulty here is the one you allude to: The assumption of Pareto optimality has become so embedded in the west that it is seen as “natural” and is therefore barely mentioned, much less questioned, in undergrad econ., even today.

Establishment of an SWF that begins with a minimum of natural resource and service stocks and then (and only then) proceeds to a sum of utilities SWF is a bridge too far for mainstream econ.

Guess where the gains from increased productivity have been going (cf Wolff)?

Instead of productivity, we should be discussing economic well-being.