The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

España se está muriendo

… su tiempo para salir de la UEM. On Wednesday I was up in freezing Iceland and we saw how the threats of being prevented entry into the EMU had led the Icelandic government into bowing to the unjustifiable bullying of the UK and Dutch governments and violating the wishes of its own populations. A greater authority (the President) intervened and hopefully the Icelanders will tell goliath to take a walk. Today I have travelled south into the EMU – to Spain where the weather is kinder but the economic climate is very harsh indeed. The situation in Spain tells us all that the Euro system was always built on corrupted neo-liberal rhetoric and now it is buckling asunder as the first real test of its logic is causing havoc among ordinary people. I am sure those officials in their warm offices and well-paid jobs in Frankfurt and Brussels are not enduring what a significant minority of Spaniards are now going through. One statistic is enough to tell you the EMU system is a failure – 53 per cent of Spanish youth (16-19 year olds) who want to work are unemployed! So … España se está muriendo … su tiempo para salir de la UEM (Spain is dying … its time to leave the EMU).

Financial Times chief economist Martin Wolf wrote on January 5, 2010 that The eurozone’s next decade will be tough. He initially posed the question:

What would have happened during the financial crisis if the euro had not existed? The short answer is that there would have been currency crises among its members. The currencies of Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain would surely have fallen sharply against the old D-Mark. That is the outcome the creators of the eurozone wished to avoid. They have been successful. But, if the exchange rate cannot adjust, something else must instead. That “something else” is the economies of peripheral eurozone member countries. They are locked into competitive disinflation against Germany, the world’s foremost exporter of very high-quality manufactures. I wish them luck.

And it was in that context that I read the latest news from Spain today which shows that the national unemployment rate in December hit 19.3 per cent (more than double the EMU average).

First, it is useful to just backstep a few years. Prior to 2008, the Spanish economy was held out as the darling of Europe however the reality was quite different when you consider it from the perspective of modern monetary theory (MMT).

Spain was running budget surpluses by 2005 and foreign investment was booming. Most of this investment went into construction which was stimulated by a massive real estate boom.

Using data from Data from the Banco de España (central bank) I graphed the national budget deficit as a percentage of GDP for Spain and the EMU overall from 1989 to 2008 (data for the EMU clearly didn’t start until 1995). You can see the tightening of fiscal positions as the Growth and Stability Pact provisions were forced on the EMU nations. By 2005 Spain was considered to be conducting highly responsible fiscal policy.

The irony is that Germany and France which were most vehement about the deficit rules in the Maastricht Treaty were the worst offenders!

The reality is that the private sector was being squeezed badly by the fiscal drag. The external position was in deficit (current account) which means the public and external balances were draining growth from the economy. Yet it still boomed up into the onset of the crisis. How did that happen?

Consistent with a tightening fiscal position leading to surpluses in 2005, the only way that this boom could continue was for the private sector to go increasingly into debt. That is exactly what happened and because the property boom was so large the debt levels were also very high – average household debt tripled

In this 2005 Banco de España Bulletin – you read (page 59):

In this setting, the volume of financing received by the private sector in Q1 continued to show notable buoyancy. In particular, corporate borrowing accelerated and its year-on-year growth stood at nearly 16%. For their part, the liabilities of households maintained a brisk pace of growth of around 20%. The breakdown of credit from resident institutions by loan purpose indicates that the most noteworthy feature between January and March continued to be the leading role of the property and construction sector.

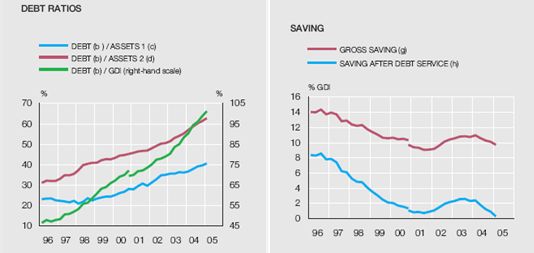

The following graph taken from the Banco de España Bulletin (modified version of their Chart 25) shows debt ratios and saving ratios for households in Spain from the mid-1990s up until 2005. The escalation in debt and declining saving was the hallmark of the period. You will find no warning in the Bulletin about these trends – the only comment made about the debt buildup is that wealth was also rising.

This is the same sort of logic that the RBA used in Australia to justify inaction on the debt buildup and to support the federal government running budget surpluses for over a decade.

And then … the global real estate market collapsed and the excessive vulnerability of the Spanish economy, which from a MMT perspective had been building for some years despite the official rhetoric, was exposed badly and the economy crashed.

Martin Wolf says:

Then came the crash. Inevitably, it hit the most extended private sectors hardest. Between 2006 and 2009, the private sectors of Ireland, Spain and Greece shifted their balances between income and spending by 16 per cent, 15 per cent and 10 per cent of GDP, respectively. The offset was also quite predictable: it was a huge deterioration in the fiscal position. This underlines a point that economists seem amazingly reluctant to take on board: the fiscal position is unsustainable if the financing of the private sector is unsustainable. In these countries, the latter was just that, with dire consequences, as the crisis made evident.

MMT does not use terms like a “huge deterioration in the fiscal position”. The huge deterioration is in the real aggregates that matter – employment and unemployment, GDP growth and the activities that generate real welfare. The change in the budget position from surplus to deficit is just a reflection of the huge swing in private spending – from a binge driven by increasing indebtedness to a rapidly rising saving ratio.

The automatic stabilisers were always going to push the budgets of the Eurozone countries into deficit. For Germany and the Netherlands, their private balances were already in surplus in contradistinction to the real estate boom countries such as Ireland and Spain so their budget swings have been of a lower magnitude.

The problem for Spain is that EMU criteria stop the budget moving sufficiently into deficit to put a floor under its collapsing economy.

It is also worth noting that for Spain the crisis has been confined to the real sector as a result of the banking system being traditionally well regulated by the authorities.

This was the first real test of the EMU system and it is clear that it is incapable of dealing with this sort of event. We will examine the reasons later.

The real damage …

The current unemployment rate for 16 to 19 year olds is 53.4 per cent; for 20 to 24 year olds – 34.7 per cent; for 25 to 29 year olds – 22.2 per cent; and the average for the rest up to 64 years of age is 14 per cent.

Where does it tell you that allowing this amount of wastage which will persist for years is a sensible policy strategy? How could anyone not understand that the losses from this amount of unemployment are so great that future generations will be carrying them in the years to come? How could it not be common sense but to allow the Spanish government to introduce widescale job creation schemes to absorb the jobless?

The following graph shows the age breakdown of that unemployment rate (data from Instituto Nacional de Estadística) from the first quarter 2005 to the third quarter 2009.

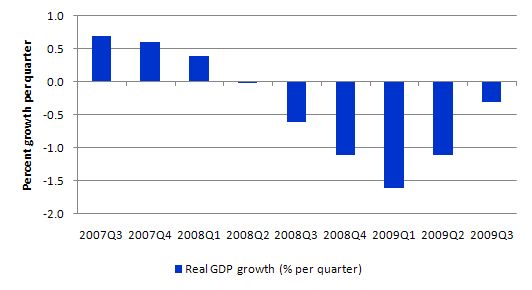

It is easy to see why this is happening. The following graph shows quarterly GDP growth rates since the onset of the recession have plummetted. The economy has had one quarter of zero growth (2008Q2) followed by 5 consecutive quarters of severe negative growth.

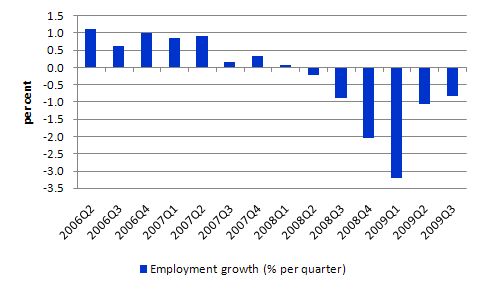

The collapse in output growth has impacted severely on the demand side of the labour market and the following graph shows employment growth (per cent per quarter) from 2006Q2 to 2009Q3, which is the very similar (as you would expect) to the evolution of GDP growth. This also tells you that the major determinant of employment is output growth which, in turn, is driven by aggregate demand (for all those who think real wage levels matter very much).

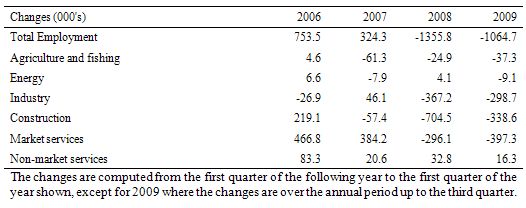

The following table shows the annual changes in employment by industry (in 000s) since 2006. So in 2008 alone a massive 1.3 million jobs were lost in net terms and in the year to September 2009 a further 1.1 million jobs were lost in net terms. The collapse of construction is evident with some 700,000 jobs lost in 2008 alone.

How did this all come about?

So how did they contrive to develop the EMU?

The EMU was justified by the concept of an Optimal Currency Area (OCA) which emerged from the work of Canadian economist Robert Mundell. The theory purports to define the conditions under which several countries should form a monetary union. It was a case of textbook theory, inapplicable to the real world, being applied to suit ideological ambitions. Yet the policy makers used the OCA literature relentlessly to give “authority” to their decisions.

Mundell defined three conditions, which if in existence, would justify the formation of a monetary union as an OCA:

- The countries should face common consequences if hit by a negative shock (no asymmetric shocks). So, for example, unemployment rates should be similar across the countries in the union;

- There should be a high degree of labor mobility and/or wage flexibility within the group of countries.

- There is a common fiscal policy that can transfer resources from better performing to poorly performing countries.

You might like to compare this list of “theoretical conditions” with what emerged out of the Maastricht theory which stipulated five conditions: convergence in interest rates, budget deficits, public debt, inflation rates and stable exchange rates prior to the formation of the union.

These conditions are not remotely like those that Mundell used to define an OCA and reflect more the blind neo-liberal ideology that was gathering pace at the time and was dominating policy makers.

The point is that the EMU countries did not (and do not) satisfy the Mundell criteria for an OCA yet they still went ahead with the common currency which meant that each sovereign nation gave up their monetary policy independence and allowed the SGP to hamstring their fiscal sovereignty.

The ability to absorb external shocks is very different across the Eurozone countries. The stronger industrial countries like Germany (who has a huge external surplus) as do the Netherlands, are in totally different situations to the capital importers such as Spain. The stronger nations can absorb shocks much better than Spain.

Finland, for example retains close cultural and trading ties to Norway and is not linked much in trade with Spain. Ireland maintained strong trading relationships with the UK and less with continental Europe.

The labour mobility criteria is required because if unemployment rises in one country, the workers are able to move within the union to find other work. Given that national identities are still strong in Europe, labour mobility is relatively low.

One of the interesting side effects of the coincidence of a major real crisis and a housing collapse is that labour mobility is now reduced (in all countries). In bad times, those that can move tend to move to chase job opportunities elsewhere. I have done a lot of work on this issue in Australia and the net migration into higher employment growth areas following a downturn is very high. It has the impact of higher skill workers squeezing out low skill workers (who already were living in the region) from jobs that the low skill would typically take. So a “bumping down” effect occurs when there are overall job shortages and regional disparities. Skilled workers are forced to move but also to take jobs that would normally go to low skill workers.

However, when there is a major real estate collapse this mobility doesn’t occur as significantly because people cannot afford to move – especially those with negative equity in their residences.

Mundell claims that this could also happen if there was wage flexibility across the union. So workers in recessed regions would reduce their wage demands and make it easier for firms to hire them. Allegedly, this would also lower prices of final goods and services produced in that region which improves their competitiveness.

So while the EMU is really a fixed exchange rate system imposed on a number of countries and so nominal exchange rate depreciation cannot occur, real terms of trade changes can happen if relative unit labour costs change.

This is how Mundell claimed it would work. The recessed nations could improve their competitive by cutting wages and unit labour costs (a real rather than a nominal depreciation) which would attract firms into that region away from other regions in the union.

Of-course, this assumes that employment is driven by wage levels. If a nation such as Spain tried to cut real wages (engineering this would be difficult in itself) then there would be a huge drop in demand by Spanish workers. It is highly unlikely that the so-called “real depreciation” impacts would offset the local income effects on demand.

One of the other constraints on mobility is that the EMU did not develop a common language. Workers are thus disadvanted when they move into a different language zone.

There is very little wage flexibility across the European economies (which is a good thing) but hardly consisten with the OCA criteria. Unions still play significant roles in wage determination and resist nominal wage cuts, especially in times of hardship.

Further, fiscal policy is unable to perform the functions that Mundell considered essential to maintain uniformity of outcomes within the nations that made up the monetary union. By construction, this reduces the capacity of sovereign governments within each individual country to respond to negative external shocks (like the current crisis).

The OCA also requires a single fiscal authority that can tranfer net spending from one region to another to even out economic performance. This criteria is absolutely essential in defining a theoretical OCA.

However, the real politik that led up to the creation of the EMU was not even remotely consistent with the criteria. Germany (and to a lesser extent France) were paranoid about the possibility that some of its southern neighbours (Italy and Spain) would use fiscal policy in an irresponsible manner. This led to the prohibitive clauses in the Growth and Stability Pact that force all EMU members to limit their budget deficits to 3 per cent of GDP or face penalties.

Only in severe recessions (a contraction of 2 per cent of GDP) could there be some leeway. Of-course, a 1.99 per cent contraction in GDP is massive and very damaging to the economy. Have a look at the GDP chart above for Spain.

If the EMU countries were serious about creating conditions consistent with an OCA they would have handed over their fiscal powers to the European Parliament. That body is relatively weak and plays no significant fiscal role.

Further there is no way that the French citizens will standby and allow its government to net spend into Spain (or even less likely to net spend into Germany).

Is the EMU an OCA? Clearly not.

In this context, Wolf noted that:

The crisis in the eurozone’s periphery is not an accident: it is inherent in the system. The weaker members have to find an escape from the trap they are in. They will receive little help: the zone has no willing spender of last resort; and the euro itself is also very strong. But they must succeed. When the eurozone was created, a huge literature emerged on whether it was an optimal currency union. We know now it was not. We are about to find out whether this matters.

The problem that the EMU system now has it that under the ridiculous rules that constrain fiscal policy, the peripheral nations now face significantly higher borrowing costs (the spreads on the benchmark 10-year German bunds have moved significantly in the last several months). Further, the criminal credit rating agencies are making matters worse by downgrading the ratings of these troubled countries.

So Spain is now trapped in a system that will punish it severely, when prior to its membership it had the fiscal capacity to reduce the damage on its citizens. Spain and the other peripheral countries are now trapped in what Wolf calls (reasonably) a “structural recession”.

The logic of the EMU (and its ridiculous Maastricht Treaty) will force these nations to engage in fiscal austerity. That will be self-defeating because there are no other adjustment mechanisms available to offset the contraction. The central bank cannot lower interest rates because the ECB rules the roost. Further there is not way they can lower their nominal or real exchange rate without inflicting further massive damage on their citizens.

The Euro is not depreciating by any major amount and remains relatively strong so there is not hope in that regard for the peripheral countries.

It is also unlikely that a reduction interest rates or depreciating real exchange rate would go anywhere near offsetting the further demand contraction that will accompany the fiscal austerity.

By construction, the fiscal austerity will cause demand to fail further and the deficit will rise not fall. This is the madness that is built into the EMU system. Discretionary fiscal changes (contractions) will fight against the automatic stabilisers as GDP contracts and the latter will win.

The problem is that the Spanish people will lose badly. But there is still 47 per cent of Spanish teenagers that they can render jobless yet!

Wold summarises the problem for the peripheral countries given the Euro overall is relatively strong like this:

This leaves peripheral countries in a trap: they cannot readily generate an external surplus; they cannot easily restart private sector borrowing; and they cannot easily sustain present fiscal deficits. Mass emigration would be a possibility, but surely not a recommendation. Mass immigration of wealthy foreigners, to live in now-cheap properties, would be far better. Yet, at worst, a lengthy slump might be needed to grind out a reduction in nominal prices and wages. Ireland seems to have accepted such a future. Spain and Greece have not. Moreover, the affected country would also suffer debt deflation: with falling nominal prices and wages, the real burden of debt denominated in euros will rise. A wave of defaults – private and even public – threaten.

I have written about the dilemmas and irrationalities several times before. Please read the following blogs – Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown – A Greek tragedy and One hell of a juxtaposition , as examples.

Conclusion

The theoretical justifications that abounded at the time of the creation of the EMU were never valid. Many professors and PhD students gained a lot of publications and research money exploring the applicability of the OCA to the EMU proposal and many skewed their research to claim that the EMU would be close to an OCA.

The reality is that it was never close and so the “optimal properties” that the literature specified were never going to be applicable. Still you heard the ideologically-driven policy makers claiming that the EMU would generate the advantages that the OCA literature claimed. It was cant of the highest order.

Further, another major problem now facing the Spanish is that “Rodriguez Zapatero and Socialists are trailing the conservative opposition according to the latest opinion polls Rodriguez Zapatero and Socialists are trailing the conservative opposition according to the latest opinion polls” (Source).

The conservatives are pledging tough fiscal policies to “reign in the deficit”. Imagine what will happen if the conservatives get back in there and start a process of fiscal consolidation?

How many more teenagers do they want to be without a job. The Spanish are trashing their future and setting up their youth for a life of disadvantage, drug and alcohol abuse, violence and crime and suicide. That is what the research literature tells us are the consequences of this sort of unemployment.

It beggars belief – the lot of it.

Digression: this is what a Job Guarantee would prevent

I happen to believe that every life is important. I think that a primary role of government is to safeguard its citizens from unnecessary death and use its fiscal powers to ensure there are enough resources devoted to this.

The UK government, in its self-imposed and illusory state of “running out of money” does agree with me. The UK Guardian carried a story yesterday entitled – Christelle and her baby died at the hands of a callous state which documented how a young woman in Britain who because she was pregnant had her income support and housing benefits withdrawn became destitute and finally “killed herself and her child.”

In 2008 she graduated from University and sought work. The jobcentre system denied her claim for jobseeker’s allowance and housing benefit because she did not have records from a cafe job she held for “eight-month period in 2003”. She was also denied access to jobseeker services because she was by then pregnant and was decreed “not in a fit condition to look for work”.

She was also denied child benefit (once it was born) because “she wasn’t on income support”. Hackney council also “demanded that she repay £200 in housing benefit which she had been given just as her jobseeker’s allowance was being taken away.”

She was denied an appeal and:

The next day she took her five-month-old son in her arms and jumped to her death from … [a] … sixth-floor balcony. Her son died in hospital some hours later.

After disovering that the “City and Hackney Safeguarding Children Board” was now conducting an enquiry, the journalist notes that “it is hard not to be struck by the contrast between the state’s reluctance to spend money on keeping Christelle alive, and its readiness to spend money on inquiring into her death.”

The journalist also notes that her concern for this case “may be a minority one”:

On websites there is a striking lack of sympathy for the Christelles of this world, and a marked resentment about the number of people demanding our collective help.

The reality is that budget deficit terrorism kills people. Next time you hear someone railing about government spending and demanding governments cut back to produce surpluses, you might wonder about this case.

The othe reality is that thousands are dying each day in less developed countries because of poverty brought about by failed neo-liberal economic programs that hamstring governments from using their capacities to improve the situation.

With a Job Guarantee in place Christelle would not be without work and would have a living wage provided to her including during the period when she was unable to work due to child-birth (before and after).

I agree with the journalist, who said of the UK system that led to the death of the mother and child:

I don’t believe this is a stance a civilised society can justify.

As an aside: I also find it particularly odd that those who fight (and kill doctors) because they demand that abortion be made illegal (they are mainly in the US) are also among those who call for small government and fiscal austerity without realising that the latter leaves millions starving and dying including innocent children who have no choice or determination in the matter. Two words: mindless hypocracy.

Saturday quiz tomorrow …

Yes, another Saturday another quiz. It will appear sometime tomorrow.

Postscript

I am experimenting with captions on the graphs. If you like or dislike the experimental formatting please let me know. I currently don’t really like it but will work on it some more. For example, I always prefer titles above the graphs so I have some CSS changes to make.

Bill,

could you please elaborate a bit on

“This also tells you that the major determinant of employment is output growth which, in turn, is driven by aggregate demand (for all those who think real wage levels matter very much).”

with regards to real wages?

I can not understand whether you sarcastic or not and what is implied by this comment. My feeling is that you are sarcastic and the story is about “aggregate wages” rather than “real wages per (employed) capita” but I want to be sure I get it right

Dear Sergei

I wasn’t being sarcastic (this time!). I was referring to the argument made by mainstream economists that unemployment arises not because aggregate demand is deficient but because workers demand real wages that exceed their marginal productivity. This issue was central to the Keynes versus the Classics debate during the Great Depression. The mainstream policies makers at the time tried to decrease wages and that made matters worse because demand collapsed even further.

In general as long as there is strong aggregate demand in the economy, if a firm can employ 1 person they can employ 100 (costs are constant in the normal operating ranges).

Hope that helps.

best wishes

bill

Bill, it is a bit different issue but on your “complete blog on one page” I can not distinguish posts (pages) I have already visited. I tried in different browsers and several computers.

It is not a big issue but quite inconvenient behavior. Should also be fixable in css and would be great. Having said it, I find it useful re-reading your posts with your cross-links even if I surely know I have read them already 😉

Bill,

Nice piece, as always. There is another irony inherent in the EMU. The idealism underlying the euro zone was that greater economic convergence would ultimately breed greater political convergence and thereby mitigate the possibility of more destructive and disastrous wars in Europe. A noble sentiment to be sure, but the self-imposed constraints inherent in the system, and their corresponding lack of political legitimacy (Germany, for example, never had the chance via referendum to vote to change the DM for the euro; it was imposed by the government) means that it is creating huge economic dislocation and breeding extremist movements within the continent (witness the rise of more right wing, populist parties, like Jean Marie Le Pen’s National Front). It is also breeding intra-European resentments, particularly anti-German sentiment. Consider the following: http://www.ethnos.gr/article.asp?catid=11378&subid=2&pubid=9304818

That’s in Greek. I’m reliably informed the last paragraph translates as:

“Germany owes us €10.5bn from the 2nd World War, they should give us that back and we can equate it all up, automatically our deficit falls to 5%…”

hmm…

The two graphs juxtaposing changes in GDP growth with changes in employment levels is excellent evidence that the correlation between output growth and employment is stronger than the correlation between wages and employment. Anyone have any ideas where I can find more evidence indicating that increasing production levels by simulating aggregate demand is a better path to take for promoting employment growth than getting workers to take large cuts in their real wages? I ask this because I’ve also seen evidence indicating the opposite is true. I can’t find the link right now, but I seem to recall reading a blog post a while back by Scott Sumner that had some interesting tables showing the NIRA’s policy of maintaining and even increasing real wage levels during the Great Depression lead to massive increases in unemployment. This seems to be contradictory to Professor Mitchell’s position that cutting real wages is not the proper course of action to take. I’m at work now and can’t access Professor Sumner’s website for some reason, but I seem to recall Professor Sumner looked at employment changes month by month over a period of three or four years. He then did some sort of a regression where he showed some of the most predictive independent variables explaining employment changes were NIRA labor policies that promoted high wage levels. When I get home I’ll try to find the link.

Perhaps Sergei could read Chapter 19 of Keynes’ book. Well ahead of its time and in many respects still kicks the pooh out of the neo-liberals lies.

Dear Sergei

I put in an a:visited class in the style sheet and it now will do what you wanted. You may not like the colour though!

best wishes

bill

This post reminded me of a couple of a few year back when ‘globalization’ was all the talk of the ‘elite’, ‘progressives’ and ‘innovators’ of our time. The language appeared to garner support for ideas like the EU and the Euro. It was mostly neo-liberal rhetoric dressed up as ‘economic development theory’ and the like. Some of the more zealous even claimed that nations would become a thing of the past, that the future world would be defined not by culture and nationality but by flows of labour and capital. Borders would cease to exist and even Africa would become happy and prosperous.

Off course that is not how things have turned out. Like most other neo-liberal rhetoric, this talk has now mostly faded into the background; returned to its cave to lick its wounds and occasionally respond emotively and aggressively when someone dares to question the failure of their ideas materialize in reality.

Just on the tragedy of Christelle and her son, the journalist’s observation that the state seemed more interested in investigating her death than in keeping her and her son alive is very acute. It speaks to the ‘media management’ world we find ourselves in today. Politicians don’t want us to hear the stories of these people. They just was us to focus on graphs and statistics that are contrived to give create the impression that we are safer, happier and healthier than we were yesterday, whether or not that is the case. Don’t think or ask questions – we will do that for you.

Dear Bill,

you are talking about colour!? What you write here is much more embarrassing than colour 😉

This is the website that has the table I was talking about earlier:

http://blogsandwikis.bentley.edu/themoneyillusion/?p=48

I can’t find the regression analysis though. Turns out the table by Professor Sumner I was referring to above looked at “industrial production” levels, not employment levels directly. I think Professor Sumner is just assuming that as industrial production decreases employment will decrease as well. Seems like a reasonable enough assumption to me. At first glance this evidence seems to contradict Professor Mitchell’s claim in this post that wage levels don’t matter much. Although, obviously there’s a lot that goes into determining employment levels besides wages. Also, these tables were produced using employment and wage data from an economy that was very different from the the one we have today. It’s too bad I can’t find that regression analysis because doing a multi-variate regression should be able to more accurately quantify which factors have the most influence on employment levels. I’ll keep looking. I’d like to see some more evidence showing the effect of rising or falling wages on employment. Does anyone have any more information besides the two graphs in this post by Professor Mitchell indicating that falling production levels and associated AD have a greater effect on employment than wage rates? Personally, I’d rather believe the falling GDP/AD story because I find it hard to believe that the problem with the U.S. economy is that wages are too high. But I’d like to see some more evidence to that effect.

Sumner appears to be deriving his conclusion by linking wage growth (wage “shocks” as he calls them) to industrial output levels and then concluding that one is the sole cause of the other.

It seems strange that he would overlook or simply disregard the fact that all of this occurred during the great depression. Had this occurred consistently during normal times, it might give me more pause. But during such a massive upheaval, it seems more sensible to first suspect that there were numerous and probably chaotic factors involved.

He disregards the fact that through all of these “wage shocks” the US steadily climbed out of depression and unemployment fell.

Here’s a blog post by Scott Summers that discusses the issue in relation to the present situation.

http://blogsandwikis.bentley.edu/themoneyillusion/?p=3388

“Now it seems like fiscal stimulus has failed, so obviously we need even more fiscal stimulus. I used to argue that every American would need to have their wage cut 8% relative to a trend line from mid-2008 to restore full employment at current levels of NGDP. I’ve never met anyone who has had that big a wage cut. With the new NGDP figures even an 8% cut relative to their normal increase wouldn’t get the job done.With the new NGDP figures even an 8% cut relative to their normal increase wouldn’t get the job done. One of three things must happen:

1. The Fed needs to produce much higher NGDP.

2. Americans need to accept far deeper cuts in their wages. And not just factory workers, not just unemployment workers, everyone needs a deep pay cut.

3. We can endure years more of high unemployment, with many lives being ruined.”

His post and the comments interesting from the MMT perspective in illustrating a contrary approach. Judge for yourself. Seems to me like they have an attitude.

Here is another interesting quote:

“We need more inflation because we need more AD. In that case you might ask; ‘why target inflation then; why not target AD directly, if that is what you are trying to increase?’ That would be a great idea! Does anyone know of a good proxy for total spending on all goods and services in the economy? If we could find such a proxy, we could simply target the growth rate of that variable, and then forget about inflation. After all, it is spending we are trying to boost, not inflation. Any suggestions?”

When I first saw those tables I also thought that something else had to be going on. It would really help if I could find the regression analysis I remember seeing somewhere that quantified the impact different policies had on employment levels. Clicking through the links Professor Sumner provides in his blog post though, I came across a paper written by Professors Harold Cole and Lee Ohanian of UCLA purporting to show that FDR’s labor policies of allowing collusion amongst many of the largest firms in the major manufacturing industries in exchange for promises to maintain high wage levels and allow union negotiated collective bargaining agreements contributed significantly to the slow pace of recovery. According to professors Cole and Ohanian, President Roosevelt’s early New Deal labor policies accounted for about 60% of the weak recovery. What professors Cole and Ohanian did was compare industrial output and associated employment levels of the major industries affected by President Roosevelt’s labor policies with employment levels for industries not covered by President Roosevelt’s policies. They also compare the output and employment levels of firms affected by Roosevelt’s labor policies with what they believe could have been achieved under some sort of a competitive model they created that is way over my head and I don’t understand at all:

http://www.economics.hawaii.edu/research/seminars/02-03/02-21.pdf (Warning: PDF file; the description of the model’s parameters starts on page 14, with a brief description of the findings on pages 12-13 and in the conclusion section on page 32)

Normally I’m skeptical of extremely complicated models that I don’t understand at all, but I will say that the recovery from the Depression did take a very long time and President Roosevelt did significantly reverse course on many of his labor policies during WWII and even slightly before. I would be interested in learning more about what MMT has to say about the relationship between wages and employment. Professor Mitchell says wage inflexibility in the Euro-Zone is a good thing, but assuming prices for goods and services are also flexible I’d think wage flexibility wouldn’t be so bad. I do realize price flexibility is a pretty big assumption though.

Question: how do we boost spending by forcing everyone to take a major pay cut? How do we spend more once we start earning less and can’t keep on borrowing?

And does “everyone” include Wall street executives?

“purporting to show that FDR’s labor policies of allowing collusion amongst many of the largest firms in the major manufacturing industries in exchange for promises to maintain high wage levels and allow union negotiated collective bargaining agreements contributed significantly to the slow pace of recovery”

I don’t have a link but I have veiwed data showing that private debt in the US had reached 240% of GDP at the time of the great crash of 1929 – second only to the level reached in the US at the time of the great crash of 2008 – and that private borrowing subsequently fell off a cliff and continued falling for around 15 consecutive years before stabalising.

Perhaps such huge private deleveraging had more to do with the slow pace of recovery?

I think the Neoclassical conclusion about employment is reached with an assumption of having a “fixed supply of money”. Since M is always M in their equations, they reach all sorts of paradoxical results.

A big problem with wage cuts is that they reduce NAD and are also virtually impossible to implement. Wage and price controls are extremely unpopular politically, for example. This is just idle theorizing that doesn’t connect to present reality. The obvious problem, which Y=C+I+NX+G shows clearly, is with aggregate demand falling short of real output capacity and that G is the only viable means to increase it quickly enough to avoid serious economic and social consequences involving loss of economic potential and waste of human resources. While politically unpopular because it is economically misunderstood, increasing NAD through appropriate fiscal policy is entirely doable, and MMT shows how and why. For example, see Bill’s three posts on deficits in the blog archive. Unfortunately, most neoliberals are still looking to monetary policy even though it has obviously failed. And many are still calling for wage cuts and breaking the unions.

The other big problem with wage cuts now is debt overhang. Neoclassical economists generally overlook this because debt – and the sharp dealing and fraud associated with the Ponzi finance that produced a lot of it – don’t figure into their models, which is why they missed the building financial crisis in the first place. Wage cuts would like accelerate debt deflation as consumers increasingly default on debt (mortgages, credit cards, auto loans, etc.) Much of the consumer debt was securitized, so this implicates the entire financial system through derivatives based on these loans. The major concern now is that debt deflation resulting from Ponzi finance in Minsky’s sense will continue to drag down the real economy with it, perhaps undermining any recovery and even resulting a global depression. Simon Johnson, for example, is now saying that we are only at the beginning of the crisis. Steve Keen and Michael Hudson have been talking about this for some time. Consolidation of power and influence has occurred instead of reform, and the TBTF doctrine has increased moral hazard. The banks are up to their old tricks, since their risk exposure is nil, with the government on the record as standing by to bail them out if needed. Indeed, so far there has been just about zero accountability, political, economic or legal, even though experts like William K. Black have said that this is a crime scene.

Tom,

Good points.

pues digamos lo que dice andrea fabra y su exquisita educación castellonense: que se jodan.