Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – April 17, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Mainstream economists use the notion of “crowding out” to argue that public spending squeezes out private spending and results in a less efficient allocation of resources overall. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) argues that the mainstream economists do not understand that the government only borrows what it has already spent. But MMT still recognise that crowding out can occur.

The answer is True.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called “financial crowding out”.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory. Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

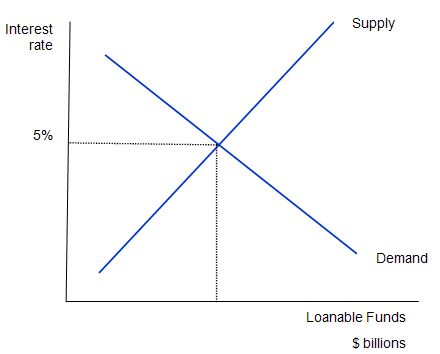

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment. Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that budget surpluses are akin to this. They are not even remotely like private saving. They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consquences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a budget deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

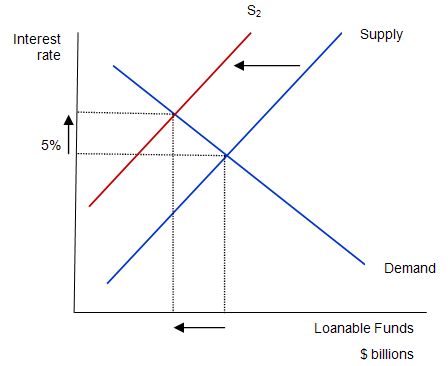

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2. Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible. In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government budgets all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these “financial” arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently. The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise budget surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios. So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues. If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

Question 2:

One interpretation of the sectoral balances decomposition of the national accounts, is that it is impossible for all governments (in all nations) to run public surpluses without impairing growth because it is likely that the private domestic sector in some countries will desire to save overall.

The answer is False.

The question has one true statement in it which if not considered in relation to the rationale for the true statement would lead one to answer True. But the rationale presented in the question is false and so the overall question is false.

The true statement is that “it is impossible for all governments (in all nations) to run public surpluses without impairing growth”. The false rationale then is that the reason the first statement is true is “because it is likely that the private domestic sector in some countries will desire to save overall”.

The question thus tests a knowledge of the sectoral balances and their interactions, the behavioural relationships that generate the flows which are summarised by decomposing the national accounts into these balances, and the constraints that is placed on the behaviour within the three sectors that is evident in the requirement that the balances must add up to zero as a matter of accounting.

Once again, here are the sectoral balances approach to the national accounts.

We can view the basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics in two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So you might have been thinking that because the private domestic sector desired to save, then the government would have to be in deficit and hence the answer was true. But, of-course, the private domestic sector is only one part of the non-government sector – the other being the external sector.

Most countries currently run external deficits. This means that if the government sector is in surplus the private domestic sector has to be in deficit.

However, some countries have to run external surpluses if there is at least one country running an external deficit. That country can depending on the relative magnitudes of the external balance and private domestic balance, run a public surplus while maintaining strong economic growth. For example, Norway.

In this case an increasing desire to save by the private domestic sector in the face of fiscal drag coming from the budget surplus can be offset by a rising external surplus with growth unimpaired. So the decline in domestic spending is compensated for by a rise in net export income.

So it becomes obvious why the rationale is false and the overall answer to the question is false.

It is impossible for all governments (in all nations) to run public surpluses without impairing growth because not all nations can run external surpluses. For nations running external deficits (the majority), public surpluses have to be associated (given the underlying behaviour that generates these aggregates) with private domestic deficits.

These deficits can keep spending going for a time but the increasing indebtedness ultimately unwinds and households and firms (whoever is carrying the debt) start to reduce their spending growth to try to manage the debt exposure. The consequence is a widening spending gap which pushes the economy into recession and, ultimately, pushes the budget into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

Please read my blogs – Stock-flow consistent macro models – Barnaby, better to walk before we run – Norway and sectoral balances – The OECD is at it again! – for more discussion on the sectoral balances.

So you can sustain economic growth with a private domestic surplus and government surplus if the external surplus is large enough. So a growth strategy can still be consistent with a public surplus. Clearly not every country can adopt this strategy given that the external positions net out to zero themselves across all trading nations. So for every external surplus recorded there has to be equal deficits spread across other nations.

Question 3:

A rising government deficit will always allow the private domestic sector to increase its saving in nominal terms.

The answer is False.

This answer should be read as a complement to the discussion in Question 2 as it also can be considered in terms of the sectoral balances.

If the external balance is zero (that is, net exports equal zero) the there is a one-to-one correspondence between the government balance and the private domestic sector balance such that, for example, a 2 per cent budget deficit must be associated with a 2 per cent private domestic sector balance surplus.

So in this circumstance the answer would be true.

But things get complicated when we introduce positive or negative external balances. Then a 2 per cent budget deficit might be associated with a 3 per cent external deficit and so the private domestic sector balance will be in deficit.

So the answer is only true if the budget deficit is larger (as a percent of GDP) than the external balance and growing faster.

Question 4:

A rising government deficit indicates an expansionary shift in policy and the challenge is to calibrate that expansion to ensure nominal demand growth does not exceed the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output.

The answer is False.

Again this question has two premises – a statement and a related consequence. In this case the statement that “rising government deficit indicates an expansionary shift in policy” is false and the related consequence that “the challenge is to calibrate that expansion to ensure nominal demand growth does not exceed the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output” is true.

Taken together the answer is false.

First, it is clearly central to the concept of fiscal sustainability that governments attempt to manage aggregate demand so that nominal growth in spending is consistent with the ability of the economy to respond to it in real terms. So full employment and price stability are connected goals and MMT demonstrates how a government can achieve both with some help from a buffer stock of jobs (the Job Guarantee).

Second, the statement that a “rising government deficit indicates an expansionary shift in policy” is exploring the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 5:

The lack of a close correspondence between the growth of bank reserves and the growth in the stock of money is evidence that credit creation has been tightly constrained by the recession.

The answer is True.

It has been demonstrated beyond doubt that there is no unique relationship of the sort characterised by the erroneous money multiplier model in mainstream economics textbooks between bank reserves and the “stock of money”.

You will note that in MMT there is very little spoken about the money supply. In an endogenous money world there is very little meaning in the aggregate.

Central banks do still publish data on various measures of “money”. The RBA, for example, provides data for:

- Currency – Private non-bank sector’s holdings of notes and coins.

- Current deposits with banks (which exclude Australian and State Government and inter-bank deposits).

- The M1 measure – Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector.

- The M3 measure – M1 plus all other ADI deposits of the private non-ADI sector. So a broader measure than M1.

- Broad money – M3 plus non-deposit borrowings from the private sector by AFIs, less the holdings of currency and bank deposits by RFCs and cash management trusts.

- Money base – Holdings of notes and coins by the private sector, plus deposits of banks with the Reserve Bank and other Reserve Bank liabilities to the private non-bank sector.

Note that ADI are Australian deposit-taking institutions; AFI are Australian financial intermediaries; and the RFCs are Registered Financial Corporations. Here is the RBA’s excellent glossary for future reference.

The mainstream theory of money and monetary policy asserts that the money supply (volume) is determined exogenously by the central bank. That is, they have the capacity to set this volume independent of the market. The monetarist portfolio approach claims that the money supply will reflect the central bank injection of high-powered (base) money and the preferences of private agents to hold that money. This is the so-called money multiplier.

So the central bank is alleged to exploit this multiplier (based on private portfolio preferences for cash and the reserve ratio of banks) and manipulate its control over base money to control the money supply.

To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in MMT. When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

A leading contributor to the endogeneous money literature is Canadian Marc Lavoie. In his 1984 article (‘The endogeneous flow of credit and the Post Keynesian theory of money’, Journal of Economic Issues, 18, 771-797) he wrote(page 774):

When entrepreneurs determine the effective demand, they must plan the level of production, prices, distributed dividends, and the average wage rate. Any production in a modern or in an “entrepreneur” economy is of a monetary nature and must involve some monetary outlays. When production is at a stationary level, it can be assumed that firms have at their disposal sufficient cash to finance their outlays. This working capital, in the aggregate, constitutes credits that have never been repaid. When firms want to increase their outlays, however, they clearly have to obtain extended credit lines or else additional loans from the banks. These flows of credit then reappear as deposits on the liability side of the balance sheets of banks when firms use these loans to remunerate their factors of production.

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply. As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans.

The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves. Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

So a rising ratio of bank reserves to some measure like M3 is consistent with the view that credit creation is being constrained by some factor – such as a recession.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

- Lost in a macroeconomics textbook again

- Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained

- Oh no … Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- 100-percent reserve banking and state banks

- Money multiplier and other myths

Bill:

Thanks for the reference to Lavoie. I found the following presentations v. helpful:

http://aix1.uottawa.ca/~robinson/Lavoie/presentations_e.html

I am having computer trouble, so I will be brief. I actually got Q. 2, right but I have a question about the explanation. To be brief, the sectoral equation,

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

does not have GDP in it. Assuming that GDP is the indicator of growth, what is the relevance of that equation to growth?

Min,

As there are no behavioral parameters given it is an identity not an equation.

With respect to growth if governments run surpluses then households will be forced into deficit and that will negatively impact upon the groth potential of the nation.

As Bill said:

“… the increasing indebtedness ultimately unwinds and households and firms (whoever is carrying the debt) start to reduce their spending growth to try to manage the debt exposure. The consequence is a widening spending gap which pushes the economy into recession and, ultimately, pushes the budget into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.”

Recessions are ultimately defined by a fall in GDP and that is why the sectorial balances identities are relevant to growth.

cheers

The lack of a close correspondence between the growth of bank reserves and the growth in the stock of money is evidence that credit creation has been tightly constrained by the recession.

SEEMS IT COULD ALSO BE THE CASE DURING AN EXPANSION THAT BANK RESERVES AND GROWTH IN ANY OF THE AGGREGATES DOESN’T ‘CORRESPOND’?

Dear Warren

It is clear that the two aggregates do not corresponde very much at the best of times. But the overwhelming reason this time can be traced to the lack of credit creation.

best wishes

bill

Dear Alan,

Thanks for your response. 🙂

The behavioral dynamics are not all that clear to me. For instance, the current embarrassment follows years of high gov’t deficits in the U. S. The connection between sectoral balances and growth does not seem all that strong.

Since my computer is behaving better, please allow me to share some of my thinking.

Before I had heard of MMT, I had reached the tentative conclusion that a fiat money system in which money is created by borrowing and lending is unstable. Why? Because it tries to extract more money out of the system than it puts in. Suppose that all debts become due on the same day (as, I have heard, in feudal Japan, where debts were due by the end of the year). Because of interest, more money has to be paid back than was lent. Some debts will not be repaid. (If there were surplus money, some of it could be passed around at the end, but we are assuming that all money is in bank accounts.) OC, in real life due dates are spread out, which masks the instability. But it seems to me that such a system has to create more and more debt, just to keep going, or debt has to be written off. In such a system, all money is not only temporary, but it cannibalizes itself. The system seems to be a machine to generate bankruptcies. Or, as some claim, a giant Ponzi scheme, where new debt is created to pay off old debt. Until, as they say, the music stops.

Occasionally, on economics blogs, I would talk about this, mostly without response. Then a remark by Bruce Wilder opened my eyes to another possibility. The government that issues the currency can run up increasing debt, which it never has to pay back. 🙂 Unlike citizens or businesses, it does not go bankrupt. The increasing government debt provides a more or less permanent supply of money, so that fewer people need to go bankrupt to feed the money machine. OC, to keep the debt growing the gov’t must run deficits.

Now, the connection between money and growth is apparent to me by what I heard in my youth: “Money is like manure. If you pile it up, it stinks, but if you spread it around it makes things grow.” 🙂

If all this is so, then there is a fairly direct connection between gov’t surpluses and impairment of growth. Government surpluses sacrifice people to the money machine.

While I do not subscribe to the Ponzi scheme view, I still have the feeling that the system is less stable than it needs to be. Consider the feudal Japanese debtors on New Year’s Eve. They could pass money around to pay debts, because it was tangible. It was not just created by entries in bank accounts. Their ability to do that provided a measure of stability to the system. The U. S. used to have tangible money, too. (We still do, but not much. ;)) We kept our gold reserves under guard at Fort Knox. We do not do that, anymore. But I think that it might add stability to the system to have a good bit of money that is not debt that has to be paid back. It would be left over when other money disappeared, and could be passed around to lubricate the system. (There are also political benefits, since people do worry about government debt.) We would still need deficits, OC, but maybe not to as great a degree as we do now.

Now, this view is rather simple, and does not get into sectoral balances. I know that many cognoscenti read this blog. I would appreciate any comments and criticism. 🙂

Min,

“The behavioral dynamics are not all that clear to me. For instance, the current embarrassment follows years of high gov’t deficits in the U. S. The connection between sectoral balances and growth does not seem all that strong.”

Government surpluses destroy high powered money and eventually force the non-government sector to spend on credit. While an economy can grow under these conditions this growth wont last forever because unlike a government who is sovereign in its own money( not to mention the ability to tax), the non-government sector will hit a credit barrier much sooner and be forced to either pay up or cease borrowing.

The non-government sector being forced to live on credit is the problem. The reason you cannot see the connection between the sectoral balances and growth is that you are forgetting that non-government spending on credit in the short was fuelling a lot of the growth.

The fact that a lot of the USA’s spending was about filling the coffers of their Military Hardware selling mates probably didn’t help either. But that’s a completely different issue.

You seem to be clutching onto the false notion that a government who taxes and is sovereign in it’s own money operates like a household.

Rather than measure debt in terms of dollars I’d prefer we measured debt in terms of people who want jobs but cannot find them.

You mentioned:

” But I think that it might add stability to the system to have a good bit of money that is not debt that has to be paid back. It would be left over when other money disappeared, and could be passed around to lubricate the system. \”

You are assuming that the government has a budget constraint in terms of it’s own money which is wrong. Hence, it\’s pretty much pointless wasting a useful commodity like gold to satisfy the whims of a few Rothbardian dinosaurs masquerading as economists.

The only reason not to run deficits would be if we already had full employment or if we wanted to subject a few million people to a dose of poverty and suffering.

Rather than measure debt in terms of dollars I’d prefer we measured debt in terms of people who want jobs but cannot find them.

Cheers, Alan

Dear Alan,

Thanks again for your response. 🙂

I see that in a number of places I have not been clear. 🙁

Alan: “Government surpluses destroy high powered money and eventually force the non-government sector to spend on credit.”

If *all* money is created by borrowing and lending, they spend on credit, anyway. Maybe not their credit, but someone’s.

Alan: “While an economy can grow under these conditions this growth wont last forever because unlike a government who is sovereign in its own money( not to mention the ability to tax), the non-government sector will hit a credit barrier much sooner and be forced to either pay up or cease borrowing.”

That is what I intended by the phrase, “until the music stops.”

Alan: “The reason you cannot see the connection between the sectoral balances and growth is that you are forgetting that non-government spending on credit in the short was fuelling a lot of the growth.”

The reason is that non-government spending on credit seems to be a feature of the system, even when the government runs a deficit. Empirically, you have the same result, even when the supposed causal condition is the opposite.

Alan: “You seem to be clutching onto the false notion that a government who taxes and is sovereign in it’s own money operates like a household.”

I have no idea why you think that. 🙁

Moi: ” But I think that it might add stability to the system to have a good bit of money that is not debt that has to be paid back. It would be left over when other money disappeared, and could be passed around to lubricate the system.”

Alan: “You are assuming that the government has a budget constraint in terms of it’s own money which is wrong.”

What constraint is that? I was obviously not clear. Here is what I had in mind:

Instead of increasing the debt when running a deficit, the government could just create money. That way you would have money that is not debt. That way, even when debts are paid back, people would have the use of that money.

Alan: “The only reason not to run deficits would be if we already had full employment or if we wanted to subject a few million people to a dose of poverty and suffering.”

As I said, not to run deficits sacrifices people to the money machine. 🙂

Min:

Instead of increasing the debt when running a deficit, the government could just create money. That way you would have money that is not debt. That way, even when debts are paid back, people would have the use of that money.

That is still debt, all money is debt. It is allways someones liability, in this case the government’s liability. Someone, has to issue liabilities.

Min: “The reason is that non-government spending on credit seems to be a feature of the system, even when the government runs a deficit. Empirically, you have the same result, even when the supposed causal condition is the opposite.”

Alan: There is a huge difference between choosing to spend on credit and being forced into it because your savings have been eroded by the fiscal consolidation fixations of the government.

In Australia non-government savings have been in rapid decline since 1996 and a large chunk of economic growth has been from consumption spending on credit.

I have no idea about other countries so what I have said may not be applicable elsewhere.

Cheers, Alan

Dear BFG,

“All money is debt.”

Mebbe so. But the money I am talking about is payable in — its equivalent.

“Here’s $10,000. Pay me what you owe me.”

“Sure. Here’s $10,000. Have a nice day. :)”

Min

Mebbe so. But the money I am talking about is payable in – its equivalent.

“Here’s $10,000. Pay me what you owe me.”

“Sure. Here’s $10,000. Have a nice day. ”

I think you have to look at it from the point of view of whose liability is attached to it. If the debt is paid back, would that not extinguish the liability attached to it, and hence destroy money. When the government credits your account, you are giving up real resources, time and effort for the governments liability, but to you that is an asset. Money is just a unit of account, it is not a thing. Now, does that mean that for profits to be made balance sheets have to keep expanding, and once they stop expanding, people pay down their debts balance sheets shrink and profits are falling? So, the government steps in to expand their balance sheets again consequently increasing profits for business.

Dear BFG,

I am afraid we’re getting off on a tangent. What I am saying is that the government does not have to issue debt to cover its deficit spending. This is what Bill Mitchell says in the “huge pack of lies” article:

“Further, sovereign governments can always decline to issue debt. While this might require some changes in regulations/laws etc, the fact is that their net spending capacity would be unaffected. The laws and institutions they have erected to force themselves to issue debt $-for-$ with net spending are all voluntary and have no economic meaning.”

That’s what I am saying, except for the part about no economic meaning. I am not sure about that. 😉 I suspect that declining to issue debt tends to produce a more stable system, but I cannot prove that.

Well, I probably am going off on a tangent. If the government didn’t issue debt to match it’s spending $-for-$, it would still count as a liability of the government for accounting purposes. But since the government is the issuer of the currency I’m sure you could look at it as a credit instrument as opposed to a debt instrument. Its not a real liability because the government is monoply issuer.