The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The bullies and the bullied

The events continue to get more strange in the Eurozone by the day. Yesterday, Portugal was downgraded, which will worsen their situation, despite the rating agency claiming that the fiscal austerity plan in place was credible. Tomorrow, European leaders meet in Brussels but the German leader doesn’t even want the crisis on the agenda. The Germans only want to discuss imposing even tougher restrictions on the ability of governments to govern in the interest of their citizens. It is like a B-grade horror movie script. But all the intrigues that are playing out in the Eurozone at present demonstrate (albeit tragically so) the dynamics that led to the collapse of the fixed exchange rate system (the Bretton Woods arrangement). Same old story – bullies and the bullied. It means the only viable solution is to abandon the EMU as soon as possible and restore some sanity … and democracy.

The Agence-France Presse release today (March 25, 2010) – Bi-partsian appeal from Portugal – brought home to me how ridiculous the economic and political aspects of human society have become. Perhaps the whole show is crazy but I will only comment on those aspects.

So now we have what I would consider to be an undignified situation where Portugal’s rulers are begging for support “for its austerity program after a downgrade in its creditworthiness shocked Europe” to stop further downgrades of their sovereign debt ratings.

Portugal has a socialist government – recall what that should mean – nationalisation of the material means of production to liberate the workers and expropriate their surplus production for the good of all rather than the benefits of a few via private (capitalist) profit.

So here we have a socialist government (as does Greece) and they want their parliament to support a plan to cause hurt and in some cases irrevocable damage to their workers and poor just because some corrupt ratings agency (Fitch), which should be irrelevant, has pronounced judgement on their fiscal position.

They said that:

Fitch Ratings has downgraded Portugal’s Long-term foreign and local currency IDRs to ‘AA-‘ from ‘AA’. The Rating Outlooks on the Long-term IDRs are Negative. Although Portugal has not been disproportionately affected by the global downturn, prospects for economic recovery are weaker than EU15 peers, which will put pressure on its public finances over the medium term.

In its press release it also claimed that the austerity measures were “credible” but decided to hurt them anyway because its “public deficit exploded in 2009”.

Just a couple of weeks ago, the OECD wrote that it:

… hails … [Portugal’s] … fiscal consolidation plan … [and said] … it will help to support growth … The OECD welcomes the authorities’ consolidation strategy, which goes in the direction of maintaining market confidence, supporting growth and ensuring fiscal sustainability.

The Portuguese government had decided to trash its economy so it could get back within the Stability and Growth Pact limits (a budget deficit below 3 per cent of GDP) by 2013. They recorded 9.3 per cent of GDP in 2009 given that the crisis was deep in Europe.

Anyway, I guess this is what Angela Merkel was aiming for by stalling off assistance talks for Greece. The Euro fell significantly overnight continuing its downward slide and making Germany more competitive by the hour.

The AFP report said that:

The downgrade was the result of “significant budgetary underperformance in 2009” as the public deficit ballooned to 9.3 per cent of output last year, higher than Fitch’s 6.5-per cent estimate.

Which just tells me that Fitch’s economists need to learn some basic skills in forecasting. Further, why is a deficit that moves to 9.3 per cent of GDP at a time the country is facing its biggest negative shock for some decades termed to be “ballooning” as if we should be shocked that the automatic stabilisers and the maintenance of social protections that US workers would love were of this magnitude?

In terms of the relative contribution of the automatic stabilisers and discretionary changes, if you examine Portugal’s response to the crisis you will see that the latter were very modest. This EC document is the sort I love – full of facts and figures.

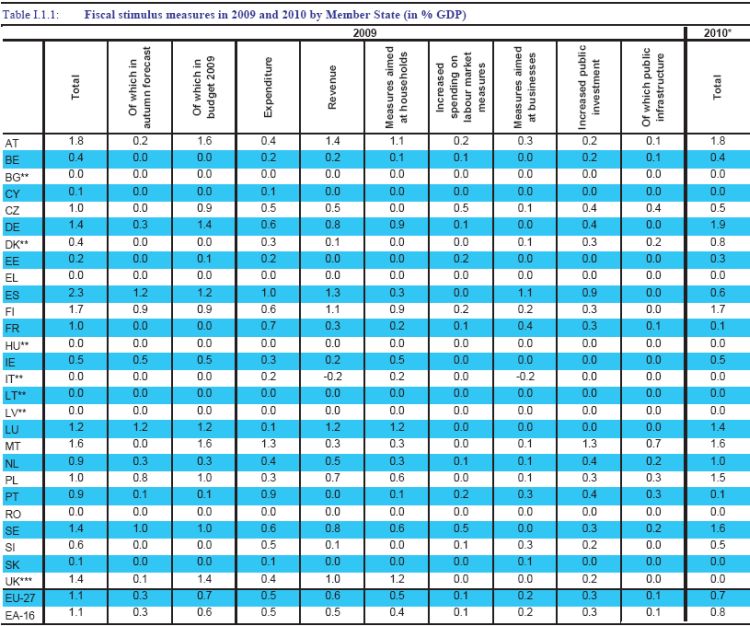

Table 1.1.1. which I reproduce below shows the fiscal stimulus measures for 2009 and 2010 (the 2010 figure in the far right column is the change since 2008).

My reading of this data is that apart from Spain, the other peripheral economies did not provide very much fiscal stimulus to their economies at all. They clearly live in fear breaching the nonsensical SGP rules that they have signed up to.

The EU say that:

In 2009 the largest fiscal stimulus in the euro area is being run in Spain, and is of the order of 2.3% of GDP; other sizeable stimuli are undertaken by Austria (1.8% of GDP), Finland (1.7%), Malta (1.6% of GDP), Germany (1.4% of GDP) and Luxembourg (1.2% of GDP).

The other interesting result they note is:

In total, i.e. also accounting for the effect of automatic stabilisers, fiscal policy is providing support to the economy in the region of 5.0% of GDP over the period 2009 and 2010, equivalent … The largest share of this overall support comes from the operation of automatic stabilisers which are particularly strong in the EU. The estimated impact of the automatic stabilisers is around 3.2% of GDP over 2009-2010.

This result is broadly applicable across the EU. So once again you would have to stretch meaning to claim that those lazy and profligate Southern Europeans have been spending up big. The budget deficits shifts scaled to the size of their economies have been heavily driven by the in-built automatic stabilisers which will go into reverse if growth was to resume.

The longer the Eurozone wallows in stagnant growth the more persistent will the budget deficits be and the larger the public debt to GDP ratios. Trying to work against the automatic stabilisers with austerity programs will be futile unless you start dismantling some of the automatic capacity.

Which is exactly what is happening at present. European countries have stronger automatic stabilisers than most other nations because they have historically given better protection to their workers and retirees etc. The push for austerity is seeking to undermine these provisions in part and in my view that is one of the hidden agendas in all of this.

It is not so much about the SGP rules (Germany and France are serial violators of those rules in the past). What Germany wants is for the other European nations to unwind social and labour protections just like they did under the Hartz reforms. They are dressing this up as a fiscal sustainability issue but the reality is they are pursuing a neo-liberal deregulation strategy that the European citizens have resisted to date.

It is clear that despite not causing the crisis or being profligate leading into the crisis Portugal must now endure an extended period or stagnant growth if not recession and the only adjustment the system will allow them to make is the so-called “competitive” one – that is, trash wages, entitlements, social protections and hand over the economy to the industrial bosses.

It is also clear that the powerhouse of the Eurozone, Germany is not about to make any concessions at all. In yesterday’s (March 24, 2010) UK Guardian – Ian Traynor writes that Eurozone leaders lock horns over whether to rescue Greece’s economy.

This is in the context of the Euro depreciating against the dollar, gold prices falling (go you gold bugs!) and the US dollar strengthening.

In relation to the Brussels summit today where Germany will push their agenda further, Traynor says that:

There were frantic efforts last night to patch up a deal, with Germany insisting on a radical rewriting of the rules for the single currency before helping Athens and chancellor Angela Merkel looking isolated but strong in dictating terms for trying to settle the worst crisis the euro has faced.

Germany now wants “to introduce draconian new conditions for the eurozone, including, in the last resort, expulsion of serially delinquent single currency countries”. The German finance minister was quoted as saying “There must be an automatic system that hurts those who persistently break the rules.”

So you naughty little kids, rulez are rulez.

Apparently:

The German wish list includes depriving fiscal sinners of EU cohesion funds and of votes in eurozone decision making councils, tougher policing of the budgets of suspect countries, and the establishment of a European Monetary Fund as a last-resort rescue vehicle. Germany wants a political commitment to change the euro system before possibly agreeing to rescuing Greece, where the debt crisis could result in a sovereign default.

So even if the deterioration is driven by the automatic stabilisers, Germany still wants to punish the nation. Who won the Second World War? This is almost macabre in its intent.

The former Belgian prime minister, Guy Verhofstadt was quoted by the Guardian as saying:

The proposals by the German chancellor are very disturbing … She declared that solidarity towards a country like Greece is not the right response. Her suggestion that consideration should be given to eventual exclusion from the eurozone is, frankly, shocking.

But even if they are singled out and hated, unchallenged bullies know who has the upper-hand. They want new tougher rules and the rest of the compliant (and begging) EMU governments will sign on the dotted lines. The bullied who don’t stand their ground will always be trodden into the ground.

The alternative view is the EC seems to be that the so-called macroeconomic imbalances have to be addressed and that Germany has to give up its position as head bully and chief exporter to its EMU colonies.

However the dominant view is that further deregulation is required. In the Economist (March 11, 2010) the article – Germany Europe’s engine – is typical of this argument.

After summarising the process of deregulation in Germany over the last 15 years, they say:

Germany is rightly proud of its ability to control costs and keep on exporting. But it also needs to recognise that its success has been won in part at the expense of its European neighbours. Germans like to believe that they made a huge sacrifice in giving up their beloved D-mark ten years ago, but they have in truth benefited more than anyone else from the euro. Almost half of Germany’s exports go to other euro-area countries that can no longer resort to devaluation to counter German competitiveness.

The Economist runs its usual line that all of “Germany’s neighbours have a great deal of work to do. France, Italy and Spain need to follow Germany in loosening up their labour markets; Italy, Spain and Greece need to tighten their public finances”. Okay, an just spread the poverty further.

But it also thinks Germany has “to push ahead with liberalisation”:

Its web of regulations is too constricting; its job protection is too rigid; its health, welfare and education systems still need big doses of change; its service sector is underdeveloped.

This apparently will “boost consumption and investment” in Germany and “would help the euro area to which it is hitched”.

It is the neo-liberal path that the West has been following for some years and resulted in crisis but along the way private indebtedness rose to unsustainable levels and it was this debt-growth that maintained consumption expenditure growth as the neo-liberal distributional shifts (from wages to profits) were being magnified.

When will we ever learn?

The “trash workers’ conditions” position is also clearly stated in the WSJ article today (syndicated in The Australian, March 25, 2010) which asserted it was – Time for eurozone shake-up.

The WSJ article says that:

Its 16 member nations now face a stark choice. They can spur economic growth across the region by following through on long-overdue pledges to trim benefits and free up labor markets. Or, many economists say, they can face a decade of economic stagnation.

So according to this mentality growth is only possible if you distribute national income to profits (by attacking working conditions and pay etc) and maintain low public sector intervention both by way of regulation and actual economic activity (employment etc).

The WSJ claim that the “(h)igher public debts and a surge of retirees will push up taxes and weigh on companies and consumers” while totally false when stated about a nation which is sovereign in its own currency is applicable to an EMU nation. They will have to “finance” their fiscal positions given the Maastricht rules and they will deflate demand.

That should give you a clue on what the appropriate solution is. Abandon the whole EMU structure and restore currency sovereignty with flexible exchange rates.

The exchange rate would address the question of “diverging competitiveness within the region”. The alternative which Germany has followed – cutting labour costs – comes at a price. It not only undermines working conditions in the country pursuing the strategy but then causes demand drains in the importing countries.

The lower wage shares undermine consumption in Germany and living standards there and rely on consumption growth elsewhere to realise the export production. But if the governments in those countries are forced to impart fiscal drag on their own economies then the deflationary vicious circle is complete.

It is totally unsustainable and provides no security against a major cyclical event – as we are now witnessing.

The current crisis and debates about rebalancing echo the type of debates that were rehearsed during the Bretton Woods years. The EMU is the ultimate fixed exchange rate system – a single currency means that parities between nations are 1 for 1 always. There is no adjustment possible. All adjustment has to be in real terms via cost structures.

So when you read politicians and commentators calling for Germany to increase its domestic demand for “its neighbours’ goods” and you read that “German politicians have countered that France and Southern European nations need to make their own industries more competitive” (source: WSJ article cited above) this is just an echo from the past.

During the Bretton Woods conference, Keynes argued that a fixed exchange rate system required nations with external surpluses to spend these surpluses in the deficit economies which ensure that growth is shared across the system. So instead of bailing out Greece, Germany just buys more olives and takes more holidays – and they achieve this by stimulating the German economy.

In a UK Guardian article (February 16, 2010) George Irvin wrote that Keynes can help the eurozone.

The basic proposition is that:

A win-win situation would result if countries such as Germany spent their surpluses in struggling neighbours’ economies

A lot of modern-day progressives still hang onto this dream and advocate fixed exchange rates

But of-course, relying on these process

Under the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate agreement, there were two types of countries – those with external deficits and those with external surpluses. The former faced continual downward pressure on their exchange rate because the supply of their currency was always greater than the demand for it (via trade). As a consequence, the governments of these countries were forced to continually deflate their domestic economies, because monetary policy had to defend the exchange rate. Fiscal policy then had to be passive to avoid the stop-go growth patterns that were common.

The domestic deflation arises because the governments had to purchase the excess supply of currency in the foreign exchange markets to maintain a balance between supply and demand at the level appropriate to hit the agreed parity.

The first problem such a government faced was a shortage of foreign reserves which it required so that it could keep buying up its own currency in the foreign exchange markets. But the domestic impacts – the resulting stagnation (high unemployment) also created massive political problems for the governments.

Taken together the incentive then was to devalue the currency (which was permitted under the Bretton Woods system).

The problem then was that other countries became disadvantaged by the devaluation of one currency and the incentive then existed for what were called “competitive devaluations” – which in net terms were clearly counter-productive.

The point is that under the Bretton Woods system, all the adjustment pressure was on the external deficit countries because they faced continual currency collapse. There was clearly a disincentive for surplus countries (given they had conned their populations into believing shipping away more real goods and services than they received back via imports was a “good thing”) to increase their own imports and restore some balance in world trade.

In the case of the EMU, devaluation is not possible so the adjustment has to be made via the labour costs and other protections. It is a race to the bottom process that these characters are advocating.

Under the Bretton Woods system, the surplus countries also stockpiled foreign currency reserves which insulated them from any currency crises and their central banks would sterilise the domestic impacts of the net exports boom by issuing bonds (to drain the domestic currency expansion that was occurring in the foreign exchange markets as the government kept the parity from rising).

In the case of the EMU, the fiscal austerity is forced on the deficit nations.

Taken together these tensions were unsustainable and that is why the fixed exchange rate system collapsed in 1971. The clear aim of Keynes’s plan was to stabilise exchange parities by redistributing the adjustment burden when trade imbalances arose.

Keynes’ plan for an international currency unit – the Bancor – is applicable to the EMU (because it has a common currency). Keynes advocated the creation of an International Clearing Union (ICU) which would hold bancor accounts for member nations and provide an overdraft facility. At the outset, the ICU would allocate bancors to each country in proportion to their trade volumes (exports and imports). The bancors would not be convertible back into gold and so would become the reserve currency.

A deficit nation would be penalised if its overdraft reached 50 per cent of its allowance. If the problem persisted then it would eventually have to devalue to head off any capital flight.

But surplus nations would lose their stock of bancors above the overdraft limit at the end of each year which would force them to shed the accumulation – presumably by increasing their demand for imports. More modern versions of the scheme suggest that a nation could provide international aid as a way of expending the surplus bancors.

The essential point is that both deficit and surplus nations would have to make adjustments in goods and services flows.

But note this is all about goods and services trading against goods and services. There is clearly separate movements in financial assets. For example, a determined speculative attack would destroy the peg very quickly just as they can undermine a flexible exchange rate. The bancor system will not improve things in this case. And it is largely these financial flows which we consider to be the dangers in a flexible exchange rate system.

History however tells us that the system was not adopted and instead Bretton Woods was introduced with the IMF becoming the main international agency and subsequently managing the SDRs.

But it is this sort of idea that is now behind the demands that Germany spends its surpluses in deficit nations.

Is it possible? Yes. Is it likely? No? The fixed-exchange rate system broke down for the same reasons – all the harsh deflationary adjustments were forced onto deficit nations and they were ultimately politically unpalatable and socially unacceptable.

Germany is clearly wanting to force these sorts of adjustments onto its partners.

But the Keynes plan was flawed anyway. Please read my blog – An international currency? Hopefully not! – for more discussion on this point.

No nation should ever surrender its capacity to issue its own currency under monopoly conditions or peg their currency to that of another.

While the ICU plan was designed to overcome the forced deflationary forces which accompany persistent external deficits, it actually cannot do that without considerable loss of sovereignty. Unless you could have one treasury and one central bank then national units are always forced to sacrifice domestic policy to maintain the value of its currency against the supra-national settlement unit.

The political point is also not to be understated. Why should a sovereign national government (and its citizens) allow an international body – like the ECB (bullied by Germany) – to implement policy that will affect its electoral appeal?

It is bad enough that we allow central bank boards who are unelected to motivate the direction of interest rates. It would be unthinkable to devolve the total fiscal and monetary authority to a supra-national body.

The other point is that the idea of a fixed exchange rate is rather illusory – speculative flows can break the peg very quickly anyway. Only countries such as China with enormous stockpiles of foreign reserves can resist these speculative attacks and run a peg against say the US dollar. But remember they have been able to build that stockpile by denying its citizens access to resources and thus keeping them poorer than they would otherwise have to be.

Finally, a deficit nation under a Bancor will still face deflationary prospects to maintain the value of its currency against the Bancor.

So the solution for the EMU remains clear to me. Disband it as soon as possible and allow the exchange rate adjustments to fix Germany up. They will never take the leadership role that Keynes envisaged at Bretton Woods.

Aside: some work I am doing at present

Some of you might know about Second Life. I toyed with the idea of starting a new economy within it to demonstrate basic Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) principles. But unfortunately, there is no flexibility with respect to currency units (you have to use their currency) and it costs quite a lot to maintain islands there.

Fortunately, there is now an open source framework (OpenSim) available which does the same thing and allows you develop a virtual world with your own currency. We are working on it now and will encourage people to migrate to our MMT Paradise in due course – if we can get it all working in a satisfactory manner.

Austrian gold bugs can come along and see whether appropriate fiscal and monetary policy settings cause hyperinflation. We will make land available at competitive prices (like free) and the second policy the Treasury will introduce is an offer of a job at a minimum wage to anyone who wants one. This policy announcement will follow immediately on from the announcement of a tax structure in the currency unit we create.

I don’t know how long it will get to create the basis infrastructure – I succeeded in creating the regional grid today on one of my test servers. But once we have some terrain and some basic infrastructure I will form a government (with a central bank and treasury) and invite people to migrate and help build our economy. Some suckers will also have to locate to the EMU zone we are creating. Others can set up residency in our version of China.

Volunteers in the development phase are also invited – let me know if you are interested.

That is enough for today!

It is time that we recognize the following.

A drive for net exports and net foreign capital inflows represent an involuntary pressure upon unit prime cost and real wages/benefits in order to mantain relative competitiveness. It becomes a mechanism to redistribute income towards profits. Thus efforts, even if they do not succeed, towards a current account surplus is another involuntary mechanism to mantain a higher profit share.

Dear Bill, What do you think of Warren Mosler’s suggestion that the ECB print and distribute one trillion Euros to each country on a per capita basis – and perhaps do this annually? Strikes me it would buy time, but doesn’t solve the basic problem, namely the different export performance as between different countries. – Ralph.

Dear Bill,

The virtual MMT world is a great idea! I am very interested and would do anything to support it!

Bill, do you have a theory as to what influences the yield curve? Seems MMT postulates that govt deficits don’t matter since the new money created (via credit from US Treasury) must eventually find its way back to the financial markets in some duration- either short-term (cash) or longer term (1yr, 5yr, 10yr, 30yr bonds) $ assets. So when money is being created and sterilized in an equal amount by the govt shouldn’t that mean that the yield curve will change in slope but never shift?

But what happens when you consider the commercial bank credit creation process- when the commercial banking sector is creating more money (via credit) that money too should eventually find its way into US govt financial assets (cash, bills, bonds). So under MMT is it not correct that a commercial bank led monetary expansion also does not lead to higher interest rates? Does that mean that money creation by both the Federal government and the commercial/shadow banking sector has no bearing on interest rates? If this is the case what do interest rates no longer indicate the degree of resource/capital scarcity? How is one to gauge the purchasing power of their money (or the erosion thereof)? Thx…

Dear Bill,

I’m interested in being involved in OpenSim in some way but at this stage not sure what possible activities might become available. It would be good if you could list a few possible activities

BTW Angela Merkel is being referred to in the latest Spiegel Online as “Maggie Merkel” – rather telling, don’t you think?

Cheers

Graham

Bill

Are there legitimate reasons for currency speculation in a fiat floating exchange rate world? I understand the legitimate uses of commodity speculation when done by producers and those that convert the commodity to an end product but I cant seem to think of “helpful” uses of currency speculation. It all seems predatory in nature. SInce fiat currency itself is not a commodity but that which all commodities are priced in, I am having a time coming up with “uses” of the currency market other than another type of casino.

Thanks

oh cool! competing economic camps setting up in virtual worlds.

I thought you didn’t go in for simulations?

Dear Scepticus

Which other economic “camp” has created a virtual world?

When have I ever said that? I do simulations often.

What you are referring to is my statement that I would not conclude anything about government policy from a highly stylised pure credit model without a government sector and which doesn’t obey fundamental rules of accounting. I would rather base conclusions of those sort on real world complex non-linear models such as Japan which has been doing every that the mainstream say you cannot do for 2 decades now with none of the mainstream outcomes.

best wishes

bill

The issues with the virtual world is that it leaves open what type of economy you are modeling.

As long as there is no mass production, or endogenous creation of capital, or invention, then you are going to be modeling a corn economy. The only asset will be real estate, and labor will be transformed into output according each person’s productivity. This won’t be a good model for an industrial economy.

To model the latter, you need not only the ability to create widgets that mass produce other widgets, given some commodity input and energy, but also the notion of invention and substitution to replace commodity inputs when they run out. E.g. as your stock of iron runs out and becomes more expensive, you can invent some alloy that uses less of it when you mass produce cars. And as your stock of coal runs out, you invent solar power or nuclear power, to power your car manufacturing plants, etc. Not to mention coming up with techniques that mass produce the cars more quickly over time.

I actually think that you could do something like this, at least to a rough degree, and it poses some interesting development challenges. It’s an exciting project. But the choices you make in how much you allow mass production and invention will determine the broad outcomes of your model, so I would be careful when drawing conclusions about the real world.

The second life economy is a perfect example — it is the Austrian’s wet dream: no government, property rights are absolute, and wages are almost solely determined by your productivity. And the gini index is about 0.9. There are no general gluts in Second Life, nor are there credit bubbles and deflation. A different currency issuance policy is not going to change the fundamental inapplicability of this model.

Are you going to add wealth/income inequality and changes in retirement dates to your simulation?

“The other point is that the idea of a fixed exchange rate is rather illusory – speculative flows can break the peg very quickly anyway. Only countries such as China with enormous stockpiles of foreign reserves can resist these speculative attacks and run a peg against say the US dollar. But remember they have been able to build that stockpile by denying its citizens access to resources and thus keeping them poorer than they would otherwise have to be.”

How about denying MOST citizens access to resources and thus keeping them poorer than they would otherwise have to be while a few have plenty? Is that happening in a lot of other countries too?

Well if the debt slaves (sorry I mean citizens) would just go into debt to the rich and the bankers, they could have more resources ~sarcasm intended~

i’m interested in mmt second life.

First time post Bill, I’ve come through Steven Keen’s website as I can’t reconcile with all he says, some of yours make me ponder and I enter your site with this one.

You said…

“We will make land available at competitive prices (like free) and the second policy the Treasury will introduce is an offer of a job at a minimum wage to anyone who wants one.”

Can I ask two questions relating to this statment?

i) How is the minimum wage determined?

ii) Does a certain and/or agreed level of (productive) output have to be acheived in obtaining this income?

Aaron, welcome. I got here from Steve’s, too. I suggest you check out complete billy blog on one page and also use the search feature. There’s a whole lot of stuff in the archive. For example, here is a post that deals with the job guarantee. Bill usually provides link within each post to other relevant posts, so the site is interlinked that way, too. Eventually, it all fits together if you follow up.

hi bill,

just a question re bank overseas borrowing. are their borrowings denominated in source country currency , and if not how does the transaction work ,accounts wise.

could you lead me to any sources looking at this process

i’m curious about our foreign debt position, and our vulnerabilities re this.

i got thinking about it, when posting on a another blog , defending mmt’s position on government deficits, of which im in broad agreement. i know , i know, your thinking with friends like these who needs enemies.

but it did get me wondering what mmt’s postion was on our foreign debt.

would be great if you could do a piece on it, if you havnt done one allready.

I agree with this post and I wrote at http://mgiannini.blogspot.com/2010/03/money-creation-for-nothing-or-let.html

– that default is the only option and at http://mgiannini.blogspot.com/2010/03/naked-gun-smell-of-fear.html

– that the plan is a naked gun put on the table by EU leaders smelling the fear and just to buy time.