I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Teaching macroeconomics students the facts

Yesterday, I was walking over to the library and I ran into an old colleague who has been dragooned back into teaching macroeconomics on a casual basis. The person was telling me that they were dreading taking the class next week because the topic was banking and the relationship between reserves and the money supply. Accordingly, the person said the chapter in the textbook specified by the lecturer-in-charge was about the money multiplier. The person I met is familiar and sympathetic to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and posed the question “how can I do it?”. My answer was that students deserved better and that the lecture should develop the multiplier from a critical perspective so that students know about it but realise how far-fetched it is as a depiction of how the banking system actually operates.

As background, I should add that I am no longer associated with the teaching faculty at the University and hold a research chair outside of the teaching and faculty structure. The research centre I direct is within the Research Division of the University. Soon after I left what was then the Economics Department, the neo-liberal managerial onslaught that is rife within Australian universities collapsed the economics discipline into a business school and wiped out a lot of the “social science” component of the program. The strongly Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and Post Keynesian teaching emphasis of the past has been largely lost and those in charge of teaching macroeconomics here are mostly mainstream (using Dornbusch of all things as the textbook – its about as bad as Mankiw!). It is a very sad outcome for students.

Anyway, I also mentioned to the person that I had just that morning been reading a rarely cited 1963 paper Commercial Banks as Creators of “Money” – by Nobel Prize winning economist (the late) James Tobin. I had read it a long-time ago while I was doing my PhD and was alerted to it again by one of the regular billy blog readers (thanks Jeff).

The article considers the money multiplier by juxtaposing the “Old View” and the “New View” of banking. I went back into my database to see the notes I took when I read the article originally (in 1983!). It is quite amazing that articles like this get lost in the mainstream literature. Despite obvious flaws they categorically demonstrate that the material that is presented in macroeconomics textbooks and which students subsequently take away from their studies as “truth” is typically misleading and often totally wrong.

Tobin begins:

Perhaps the greatest moment of triumph for the elementary economics teacher is his exposition of the multiple creation of bank and credit deposits. Before the admiring eyes of freshmen he puts to rout the practical banker who is so sure he “lends only the money depositors entrust to him.” … [in fact] … depositors entrust to bankers whatever amounts the bankers lend … [for] … the banking system as a whole …. a long line of financial heretics have been right in speaking of “fountain pen money” – money created by the stroke of the bank president’s pen when he approves a loan and credits the proceeds to the borrower’s checking account.

In the blog – Money multiplier and other myths – I provide an elementary account of the money multiplier that is taught to students. This is a central mainstream concept which underpins its view that inflation results from budget deficits and that the central bank can control the money supply.

The mainstream macroeconomics textbooks tell students that monetary policy describes the processes by which the central bank determines the money supply. In Mankiw’s Principles of Economics (Chapter 27 First Edition) he says that the central bank has “two related jobs”. The first is to “regulate the banks and ensure the health of the financial system” and the second “and more important job”:

… is to control the quantity of money that is made available to the economy, called the money supply. Decisions by policymakers concerning the money supply constitute monetary policy (emphasis in original).

They link this alleged capacity to control the money supply to inflation via the belief in the now-discredited but still prominent Quantity Theory of Money.

Textbooks like that of Mankiw mislead their students into thinking that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. They claim that the central bank “controls the money supply by buying and selling government bonds in open-market operations” and that the private banks then create multiples of the base via credit-creation.

Students are familiar with the pages of textbook space wasted on explaining the erroneous concept of the money multiplier where a banks are alleged (according to Mankiw) to “loan out some of its reserves and create money”. As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations.

Allegedly, the money multiplier m transmits changes in the so-called monetary base (MB) (the sum of bank reserves and currency at issue) into changes in the money supply (M).

Students then labour through algebra of varying complexity depending on their level of study (they get bombarded with this nonsense several times throughout a typical economics degree) to derive the m, which is most simply expressed as the inverse of the required reserve ratio.

So if the central bank told private banks that they had to keep 10 per cent of total deposits as reserves then the required reserve ratio (RRR) would be 0.10 and m would equal 1/0.10 = 10. More complicated formulae are derived when you consider that people also will want to hold some of their deposits as cash. But these complications do not add anything to the story.

The formula for the determination of the money supply is: M = m x MB. So if a $1 is newly deposited in a bank, the money supply will rise (be multiplied) by $10 (if the RRR = 0.10). The way this multiplier is alleged to work is explained as follows (assuming the bank is required to hold 10 per cent of all deposits as reserves):

- A person deposits say $100 in a bank.

- To make money, the bank then loans the remaining $90 to a customer.

- They spend the money and the recipient of the funds deposits it with their bank.

- That bank then lends 0.9 times $90 = $81 (keeping 0.10 in reserve as required).

- And so on until the loans become so small that they dissolve to zero

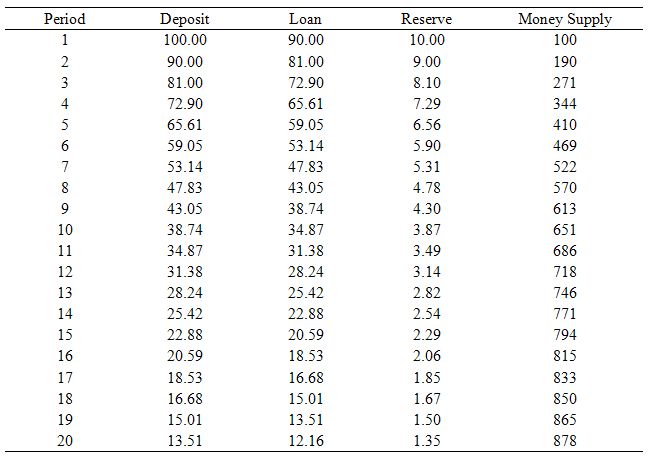

The following table shows you what the pattern involved is. The results are self-explanatory. In this particular case, I have shown only 20 sequences. In fact, this example would resolve at around 94 iterations where the successive loans, then fractional deposits get smaller and smaller and eventually become zero.

The conception of the money multiplier is really as simple as that. But while simple it is also wrong to the core! What it implies is that banks first of all take deposits to get funds which they can then on-lend. But prudential regulations require they keep a little in reserve. So we get this credit creation process ballooning out due to the fractional reserve requirements.

That is nothing like the way the banking system operates in the real world. The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government”.

This leads to claims that if the government runs a budget deficit then it has to issue bonds to avoid causing hyperinflation. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Further, the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply in a modern monetary system. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank. The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

Tobin clearly knew this in 1963. After presenting the mainstream view of the money multiplier he said:

The foregoing is admittedly a caricature, but I believe it is not a great exaggeration of the impressions conveyed by economics teaching concerning the role of commercial banks … in the monetary system. In conveying this melange of propositions, economics has replace the naive fallacy of composition of the banker with other half-truths perhaps equally misleading.

Tobin then argues that this old way of thinking – which links the behaviour of the financial and monetary institutions with the real economy – ultimately via the Quantity Theory of Money – is inferior to a “new view” which is more ground in the world of the “practical banker”. The new view:

tends to blur the sharp traditional distinctions between money and other assets and between commercial banks and other financial intermediaries; to focus on demands for and supplies of the whole spectrum of assets rather than on the quantity and velocity of “money”; and to regard the structure of interest rates, asset yields, and credit availabilities rather than the quantity of money as the linkage between monetary and financial institutions and the policies on the one hand and the real economy on the other.

So financial intermediaries including banks aim to bring together borrowers “who wish to expand their holdings of real assets … beyond the limits of their own net worth” and lenders “who wish to hold part or all of their net worth in assets of stable monetary value with negligible risk of default”. The assets of the banks are the obligations of the borrowers (loans etc) while the liabilities are the assets of the lenders (deposits etc).

Interestingly – and gold bugs take note – Tobin says that:

Neither individually nor collectively do commercial banks possess a widow’s cruse. Quite apart from legal reserve requirements, commercial banks are limited in scale by the same kinds of economic processes that determine the size of other intermediaries.

The way banks actually operate is to seek to attract credit-worthy customers to which they can loan funds to and thereby make profit. What constitutes credit-worthiness varies over the business cycle and so lending standards become more lax at boom times as banks chase market share.

So there is a limit on bank lending imposed by the opportunities to profit and the availability of credit-worthy customers.

His Section V entitled – Fountain Pens and Printing Presses is especially interesting although I would use different terminology (especially with respect to the “printing press” characterisation).

Tobin says:

Evidently the fountain pens of commercial bankers are essentially different from the printing presses of governments. Confusion results from concluding that because bank deposits are like currency in one respect – both serve as media of exchange – they are like currency in every respect. Unlike governments, bankers cannot create means of payment to finance their own purchases of goods and services. Bank-created “money” is a liability, which must be matched on the other side of the balance sheet.

This goes to the heart of the difference between vertical and horizontal transactions which define the relationship, in the first instance (vertical), between the government and non-government sector and, in the second instance (horizontal) between transactors within the non-government sector.

I cover these concepts in some detail in the suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The following diagram is taken from Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 and allows you to understand the difference between vertical and horizontal transactions within a modern monetary system.

In terms of the vertical transactions between the government and non-government sector, the tax liability is characterised as being at the bottom of the vertical, exogenous, component of the currency. The consolidated government sector (the Treasury and RBA) is at the top of the vertical chain because it is the sole issuer of currency.

The middle section of the graph is occupied by the private (non-government) sector. It exchanges goods and services for the currency units of the state, pays taxes, and accumulates the residual (which is in an accounting sense the federal deficit spending) in the form of cash in circulation, reserves (bank balances held by the commercial banks at the central bank) or government (Treasury) bonds or securities (deposits; offered by the central bank).

The currency units used for the payment of taxes are consumed (destroyed) in the process of payment. Given the national government can issue paper currency units or accounting information at the central bank at will, tax payments do not provide the state with any additional capacity (reflux) to spend.

The two arms of government (treasury and central bank) have an impact on the stock of accumulated financial assets in the non-government sector and the composition of the assets. The government deficit (treasury operation) determines the cumulative stock of financial assets in the private sector. Central bank decisions then determine the composition of this stock in terms of notes and coins (cash), bank reserves (clearing balances) and government bonds.

Tobin says in this regard:

Once created, printing press money cannot be extinguished, except by reversal of the budget policies which led to its birth. The community cannot get rid of its currency supply; the economy must adjust until it is willingly absorbed. The “hot potato” analogy truly applies.

To further understand what happens at the macro level he observes that the “preferences of the public normally play no role in determining the total volume of deposits or the total quantity of money. For it is the beginning of wisdom in monetary economics to observe that money is like the “hot potato” of a children’s game: one individual may pass it to another, but the group as a whole cannot get rid of it. This is as true, evidently, of money created by banker’s fountain pens as of money created by public printing presses.

But the important point is that portfolio preferences may be disturbed when, for example, a budget deficit adds bank reserves (high powered money) to the non-government sector. Economic adjustments then occur to resolve the desires of the private sector to hold different financial assets according to their yields and risks.

The diagram shows how the cumulative stock is held in what we term the Non-government Tin Shed which stores fiat currency stocks, bank reserves and government bonds. I invented this Tin Shed analogy to disabuse the public of the notion that somewhere within a nation there is a store where the national government puts its surpluses away for later use. There is actually no storage (that is, saving) because when a surplus is run, the purchasing power is destroyed forever. However, the non-government sector certainly does have a Tin Shed within the banking system and elsewhere.

Any payment flows from the Government sector to the Non-government sector that do not finance the taxation liabilities remain in the Non-government sector as cash, reserves or bonds. So we can understand any storage of financial assets in the Tin Shed as being the reflection of the cumulative budget deficits.

Taxes are at the bottom of the exogenous vertical chain and go to rubbish, which emphasises that they do not finance anything. While taxes reduce balances in private sector bank accounts, the Government doesn’t actually get anything – the reductions are accounted for but go nowhere. Thus the concept of a fiat-issuing Government saving in its own currency is of no relevance.

Finally, payments for bond sales are also accounted for as a drain on liquidity but then also scrapped.

The US government regularly trashes US currency notes that it collects as taxes which suggests that the “revenue” goes into the trash bin rather than is used to underpin spending!

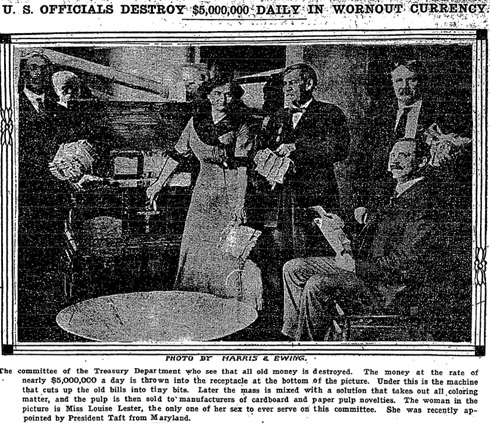

As an aside, in the following news story you learn that the revenue also might go into recycled paper and cardboard products. The US Government was looking green in 1912!

My friend and some-time co-author Randy Wray sent me a link to a photo the other day. I did some further research and determined that the photo was part of the famous Harris and Ewing Inc. collection which was donated to the US Library of Congress in 1955.

The photo appeared in an article published by the Washington Post on June 2, 1912 and it shows officials from the “US Treasury Department, Bureau of Printing and Engraving. Destruction Committee” destroying old US currency notes. The woman is one Mrs. Louise Lester who was apparently “in charge of mutilation” and the only woman to have served in this role up to that point in history.

Here is the image from the original Washington Post story from 1912. If you want to see a clearer image of the original photo used in the story then click the photo.

Anyway, back to the story.

The private credit markets represent relationships (depicted by horizontal arrows) and house the leveraging of credit activity by commercial banks, business firms, and households (including foreigners), which many economists in the Post Keynesian tradition consider to be endogenous circuits of money. The crucial distinction is that the horizontal transactions do not create net financial assets – all assets created are matched by a liability of equivalent magnitude so all transactions net to zero.

This is the sense that Tobin says that every banking asset is matched by an offsetting liability. While the non-government sector cannot create or destroy net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue, Tobin says of “bank-created money” that:

… there is an economic mechanism of extinction as well as creation, contraction as well as expansion. If bank deposits are excessive relative to public preferences, they will tend to decline; otherwise banks will lose income. The burden of adaption is not placed entirely on the rest of the economy.

So when a loan is paid off the liability and asset is extinguished and the broad measure of the “money supply” shrinks. However, transactions within the non-government cannot reduce the level of bank reserves. They can redistribute them but not alter the net cash position of the economy. Only vertical transactions can change the net cash position.

Tobin then considers the textbook treatment of monetary expansion. He says that according to this mainstream view, “additional reserves make it possible and profitable for banks to acquire additional earning assets. The expansion process lowers interest rates generally – enough to induce the public to hold additional deposits but … not enough to wipe out the banks’ margin between the value and cost of additional deposits.”

He concludes:

But the textbook description of multiple expansion of credit and deposits on a given reserve base is misleading even for a regime of reserve requirements. There is more to the determination of the volume of bank deposits than the arithmetic of reserve supplies and reserve ratios. The redundant reserves of the thirties are a dramatic reminder that economic opportunities sometimes prevail over reserve calculations.

Again, the terminology is mainstream. But the importance of this point is that it undermines the notion that reserves are loaned on a fractional basis and are thus “multiplied” into the money supply.

What determines banks’ willingness to extend loans is not the volume of reserves in the system but rather the demand by credit-worthy borrowers (“economic opportunities”) who the banks’ estimate will deliver a risk-tolerant return on their capital.

In relation to the diagram above, private leveraging activity, which nets to zero, is not an operative part of the “Tin Shed” stores of currency, reserves or government bonds. The commercial banks do not need reserves to generate credit, contrary to the popular representation in standard textbooks.

Tobin continued to argue that the mainstream textbook approach dismissed the 1930s build-up of “redundant reserves” (while the broader money aggregates collapsed) “simply as an aberration from the normal state of affairs in which banks are fully ‘loaned up’ and total deposits are linked to the volume of reserves”.

The same point is being made in the current period after the rather dramatic balance sheet expansions of the central banks via quantitative easing. The broad money aggregates are static or shrinking yet the major central banks are holding massive increases in bank reserves.

Tobin correctly says:

The thirties exemplify in extreme form a phenomenon which is always in some degree present … An individual bank is not constrained by any fixed quantum of reserves. It can obtain additional reserves to meet requirements by borrowing from the Federal Reserve, by buying “Federal Funds” from other banks, by selling or ‘running off’ short-term securities. In short, reserves are available at the discount window and in the money market, at a price. This cost the bank must compare with available yields on loans and investments. If those yields are low relative to the cost of reserves, the bank will seek to avoid borrowing reserves and perhaps hold excess reserves instead. If those yields are high relative to the cost of borrowing reserves, the banks will shun excess reserves and borrow reserves occasionally or even regularly.

Thus, the extent to which the central bank supply of reserves is used “depends on the economic circumstances confronting the banks – on available lending opportunities and on the whole structure of interest rates from the Fed’s discount rate through the rates on mortgages and long-term securities.”

The upshot of these insights is that there is a “much looser linkage between reserves and deposits than is suggested by the textbook exposition of multiple expansion for a system which is always precisely and fully ‘loaned up'”.

So Tobin clearly understood that a growth in the supply of reserves will not necessarily be related in any particular way to the growth in broader monetary aggregates, as is assumed by the mainstream and taught day-in-day-out to students studying macroeconomics.

He also notes that “loans and deposits will expand by less than their textbook multiples” because the “open-market operations which bring about the increased supply of reserves tend to lower interest rates” which “diminish the incentives of banks to keep fully loaned up or to borrow reserves”.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

So the way the monetary system actually works is that bank reserves are not required to make loans and there is no monetary multiplier mechanism at work as described in the text books.

Loans create deposits which can then be drawn upon by the borrower. No reserves are needed at that stage. The loan desk of commercial banks has no interaction with the reserve management desk as part of their daily tasks. They just take applications from credit worthy customers who seek loans and assess them accordingly and then approve or reject the loans. In approving a loan they instantly create a deposit.

The only thing that constrains the bank loan desks from expanding credit is a lack of credit-worthy applicants, which can originate from the supply side if banks adopt pessimistic assessments or the demand side if credit-worthy customers are loathe to seek loans.

It is also possible that the price that the central bank sets at the discount window may influence the profitability of certain loan opportunities for banks and curtail lending.

Conclusion

I hope my former colleague, who I bumped into yesterday, doesn’t follow the textbook and force the monetary multiplier as presented onto the students. I hope that instead, the students are exposed to the concept as a classic example of the way the mainstream profession misleads the students.

I also hope that by the end of the lecture they are thoroughly dis-abused of the concept.

I also hope that my former colleague then traces out how the mainstream uses these erroneous concepts to mount ideological attacks on governments and force them to introduce macroeconomic policy settings that are not consistent with the pursuit of public purpose. Specifically, I hope the students realise after the lecture that the claims that budget deficits will lead to hyperinflation if the government stopped placing debt into the private markets when they net spend are totally without theoretical foundation.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

Hey Bill

This is off the topic of your post today but I was wondering if you might not take your story telling skills and create a story around a family who tries to have a gold standard, or some fixed exchange rate system, instead of the fiat business card economy. That business card economy has served very well as an illustration of the basics of MMT operations when I talk to friends but many still dont see the advantage relative to a money system based on a gold standard. I feel like I’m fighting out of my weight class when I try to really compare the strengths and weaknesses of the two. I know

what you say feels and sounds right to me but I’m not versed enough to really deliver the proper critique to the gold standard system and I need an illustration.

Thanks

I second Wally on that. It would be really useful to have a simple but correct model comparing and contrasting convertible fixed rate systems and non-convertible flexible rate ones, both for personal understanding of the essentials and also to refer people to.

The most straightforward way to destroy the money multiplier from within is to have one “small, local bank in the system” come up with the “brilliant idea (perhaps they read the foreign newspapers about how banks do things over the border from Textbooklandistan in Realworldia)” to add a second class of deposit with different reserve ratios, eg Certificates of Deposit. Then (waving hands that they are one bank among many, so the multiplier “wouldn’t change much”), how much of their deposits do they need to shift from ordinary deposits to CD’s to “free up” the reserves to lend $200,000.

Then, “of course, if every bank does this (as every bank does in Australia, the US, Japan and Europe, for some minor examples)”, then the money multiplier itself will increase when banks pull deposits into lower reserve accounts with interest rate premiums, and decrease when banks drop premiums and allow deposits to slide back toward higher reserve accounts”.

Then if the size of the multiplier is the bank’s plaything, the FRB can’t control the money supply via the MB, but can, of course, control the underlying cost of funds by draining or injecting reserves into the system.

That covers the mechanics, while poisoning the well on the neolib indoctrination into a false model of the monetary system.

I also second Wally. 🙂 I would also like it if you would address this impression that I have about the gold standard, that it enforces discipline, but discipline of the wrong sort, namely pro-cyclical discipline. Thanks. 🙂

When I was starting out trying to understand this business of money, resolving the apparent contradiction between ‘banks create money’ and ‘banks have to raise money to lend’ was one of the hardest things to get right. Both seem, on the face of it, to be completely accurate, yet in complete contradiction. (This is probably very basic for many readers of Bill’s blog, but I think not for all of us). So here is how I resolved them.

Banks do indeed create the ‘money’ they lend, but they also have to borrow the money they lend. The apparent contradiction comes from misunderstanding what money is.

Firstly, banks do not create ‘money’ per se : they create deposits. Deposits look like money to us mere mortals; after all, that’s what we do virtually all our shopping with. But a deposit is nothing more than an IOU from a bank – a promise to pay you – and banks happens to be very reliable. To say ‘banks can create money’ is really just to say that anyone can write an IOU, and if the person writing an IOU is reliable and well-known enough then that IOU is as good as cash.

But if deposits are really IOUs, it is obvious that banks need to pay them back, like any IOU. In practice, they get the money to ‘pay them back’ by borrowing off other people, in the form of accepting deposits or directly raising funds in financial markets. The fact that the ‘money’ the banks raise is mainly just IOUs from themselves or other banks is irrelevant – the ‘money’ is just as good for the bank as it is for you or anyone else. Of course, all the money the bank borrows has to be paid for with interest (‘cost of funds’) and is subject to the real constraints of capital requirements (the Basel Accords) – hence banks have no ‘widows cruse’ (awesome reference by Tobin there).

Taking it one step further, ‘real money’ – cash and bank reserves – is just a form of IOU as well; it is an IOU from a government, who are the most reliable and well-known issuers of all. Similarly, bonds and other financial instruments are IOUs, just on slightly different terms and with varying degrees of reliability. In fact, the whole ‘financial industry’, when you get down to it, consists of people writing promises and exchanging them for other promises.

The key idea is to stop thinking of money (and all other financial instruments) as being a sort of ‘commodity’ and to start thinking of them as exchangeable promises (IOUs). These promises behave somewhat like commodities for individuals and firms, but in aggregate they are no such thing. Once you do this, the apparent contradictions resolve themselves. Results like ‘the money supply expands based on banks ability to find worthwhile creditors’ and ‘private sector – horizontal – transactions do not create net financial assets’ fall out naturally.

Anyway, here’s hoping that this description is a) useful to other newbies like myself and b) not totally off the money in the eyes of those more knowledgeable (of which this blog is a rich source) 🙂

Dear Wally, Min and Tom

I will see what I can do. Stay tuned.

It is immediately quite difficult because there has to be a foreign sector (some neighbours) from the outset which adds complexity. But I will do some musing on it and we will see what comes out of that.

best wishes

bill

“So the way the monetary system actually works is that bank reserves are not required to make loans and there is no monetary multiplier mechanism at work as described in the text books.”

So if banks do not require reserves to make loans, does it follow that giving Goldman Sachs and other large investment banks access to the federal reserve discount window is not such a big deal? Many progressive commentators like to make the argument that banks are able to borrow extremely cheaply from the Federal Reserve and then turn around and lend to consumers at exorbitantly high rates. This constitutes a huge subsidy to the banking community. See for example Arjun Jayadev writing at New Deal 2.0:

http://www.newdeal20.org/2010/04/30/the-gift-from-borrowers-to-banks-10290/

“Citi and many other banks now operate a relatively riskless operation-borrowing from the Fed and savers at sharply lower interest rates but lending out to the government, consumers and corporations at rates that have not fallen in tandem…Note that since the last quarter, they’ve [large investment banks] ramped up short-term borrowings by 40% on their liabilities side from $131 to $180 billion, or a difference of $51 billion. They are paying less interest on this than before-a difference of 28 basis points (0.9-0.62) on average. Now, look at their investments. Citi ramped up consumer loans by $95 billion (from $442 to $538 billion). The interest rate on consumer loans has, rather than coming down, actually increased by 160 basis points, from 8.13% to 9.73%…”

But if the reserves banks can obtain through the discount window are not in fact “lent out,” that seems to me to render Mr. Jayadev’s argument ineffective. If banks don’t lend out the reserves they borrow from the fed, then who cares how cheaply they can borrow? This seems to imply there is no subsidy. On the other hand, the financial sector, or at least the upper echelons of the financial sector, certainly has been able to maintain its profitability through these difficult economic times. If the borrow short at cheap rates, lend long at much higher rates (what I’ve seen some economists refer to as “maturity transformation”) subsidy doesn’t exist, how are the banks able to make so much money?

begruntled,

You should read the following if you haven’t already, by Mitchell Innes that was published in The Banking Law Journal, May 1913 on that question WHAT IS MONEY?. Warren, also has it posted on his mandatory reading list. It’s a bit longer than Bill’s posts but it’s worth the read.

capital vs. reserves

I recommend JKH’s 5:32 comment at this link:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2009/11/money-banks-loans-reserves-capital-and-loan-officers.html

Press CTRL + F on the keyboard and then type 4:50 is the easiest way to get there.

It starts with “Nick,

A thought provoking post, thanks. It prompted me to flesh out a model of my own. Apologies for the length of this “comment”; it will require someone to have an unusual level of interest in order to read it.”

“Teaching macroeconomics students the facts”

I think it would be quite helpful if students were correctly taught the difference between spending with currency and spending with debt.

NKlein1553,

You skipped right past a key distinction … giving Investment Banks access to the Federal reserve discount window.

Commercial banks clear payments, and so provided they can continue to clear payments, their account liabilities are money (Bill Mitchell’s “horizontal” money). Investment Banks, by contrast, specialize in the operations requires to create new financial assets to be sold (and resold and resold and resold – sometimes within a fraction of a second, as we saw on Thursday) on capital markets.

An intrinsic part of underwriting corporate debentures and issues of corporate shares is that the underwriter must be able to hold some of the assets and, indeed, ought to hold some of the assets that they are underwriting. And from hard experience, commercial banks ought not be involved in that.

The separation of Investment Banking and Commercial Banking means that Investment Banks cannot create the money to lend to buyers of new financial assets being underwritten. Given the fact that this activity generates immediate underwriting income while a substantial share of the risk of the lending is systemic risks that can be undervalued during a bull market, allowing this creates a substantial bias toward bubbles in capital markets.

It was not only a mistake to eliminate the firewall between commercial and investment banking, it was a mistake to allow investment banks to incorporate and go public.

Dear Bill,

I just wanted to tell you how shocked I am that your University is not utilizing your great teaching skills shown in all of your blog posts and your regular Weekend questions/answers. I know that this probably better for you because it gives you more time for your research but is a disgrace for your University to deny its students the opportynity to learn from you. I wanted you to know that which I hope you allow me to share it in your blog!

Regards,

Panayotis

@bfg

Thanks for that awesome article. The historical view – that it has always been thus, and the idea of commodity money is a recent insanity that has never really worked – had not occurred to me.

I don’t know whether to be pleased to find this perspective to be as old as 1913 (or indeed earlier) or horrified that one hundred years later governments and economists still don’t seem to get it.

Dear Panayotis

Thanks very much for your kind comments. The decision was mine to leave the teaching faculty and concentrate on running my research centre – CofFEE. At the time, I made the decision I still planned to teach the macroeconomic courses within the department. But events overtook that idea and the neo-liberals have taken over the very progressive program which I had helped set in place. Economics is under attack here as elsewhere by the conservatives and the growth of so-called business education, which is in fact a non-education and would be better called an indoctrination.

For me, the choice was to build a MMT haven (CofFEE) and maintain my PhD supervision within that structure or get involved in endless warfare with mindless managers. I chose the option that gave our research group the most freedom and the most peace. I think I made the correct choice as I am not bound by any of the mindless rules that are now imposed on academics in the name of efficiency. It is such a joke that anyone from outer space who looked in on our system would just think humanity just crawled out of the slime.

My blog is in part my offering to students everywhere who are forced to endure the endless lies that are offered up by mainstream economics programs everywhere. You and I have both endured those programs in the past and wasted hours of our lives reading the tripe that is served up in the name of education.

Randy Wray and I are also finishing off a MMT textbook which we hope will provide students with a viable alternative to the mainstream textbooks that they are forced to use.

best wishes

bill

NKlein1553’s post said:

“”Citi and many other banks now operate a relatively riskless operation-borrowing from the Fed and savers at sharply lower interest rates but lending out to the government, consumers and corporations at rates that have not fallen in tandem…Note that since the last quarter, they’ve [large investment banks] ramped up short-term borrowings by 40% on their liabilities side from $131 to $180 billion, or a difference of $51 billion. They are paying less interest on this than before-a difference of 28 basis points (0.9-0.62) on average. Now, look at their investments. Citi ramped up consumer loans by $95 billion (from $442 to $538 billion). The interest rate on consumer loans has, rather than coming down, actually increased by 160 basis points, from 8.13% to 9.73%…”

But if the reserves banks can obtain through the discount window are not in fact “lent out,” that seems to me to render Mr. Jayadev’s argument ineffective. If banks don’t lend out the reserves they borrow from the fed, then who cares how cheaply they can borrow? This seems to imply there is no subsidy. On the other hand, the financial sector, or at least the upper echelons of the financial sector, certainly has been able to maintain its profitability through these difficult economic times. If the borrow short at cheap rates, lend long at much higher rates (what I’ve seen some economists refer to as “maturity transformation”) subsidy doesn’t exist, how are the banks able to make so much money?”

I’m not sure this is correct, but from what I have read at various places, here is my explanation.

You need to take capital and losses into account. Let’s assume the “bank” has enough capital (if it didn’t rates for risky lending should go up to the point no entity can borrow) for some risky loans. Next, the asset for the “bank” (the loan) and the liability for the “bank” (the demand deposit) are created at the same time “out of thin air”. The demand deposit is given to the borrower who usually spends it. The demand deposit moves all around the economy. Eventually, it could end up at another “bank”. The first “bank” needs some type of demand deposit for its liability side of the balance sheet. If the second “bank” believes the first “bank” is solvent, I think it should somehow let the first “bank” have its demand deposit back. This completes the balance sheet of the first “bank”. The first “bank” makes some of its earnings based on the spread between the interest rate of the loan and the interest rate of the deposit. It seems to me that the fed funds rate influences the rate paid on the demand deposit. A lower rate paid on the demand deposit widens the spread meaning more profitability on the loan. I would say there is your “subsidy”, the lower rate paid on the demand deposit, which hits people who are looking for a riskless interest rate.

I believe the earnings on the spread between the loan interest rate and the demand deposit interest rate can then be used as capital if the “bank” so desires.

There is a difference between a “bank” lending out in the “riskless” overnight market and other types of lending.

For anyone, feel free to correct my model and/or terminology.

NKlein1553’s post said:

“Citi and many other banks now operate a relatively riskless operation-borrowing from the Fed and savers at sharply lower interest rates but lending out to the government, consumers and corporations at rates that have not fallen in tandem…”

I would say relative riskless depends on the size and number of debt defaults on the loans.

Let’s say an economy has about 1 trillion in currency and very little gold. This economy then experiences loan losses of 2 to 3 trillion. What happens?

I think I heard JKH once say that the reserve multiplier is actually a capital multiplier. Is that correct?

Dear Fed Up

Who holds the currency?

Who experiences the losses?

Who is the counterparty?

best wishes

bill

Who holds the currency? ******* as bank capital at various banks

Who experiences the losses? *** the banks or originators

Who is the counterparty? ****** not sure

Bruce,

So are you saying commercial banks do not use reserves obtained from the federal reserve to make loans, but investment banks do use these reserves to create new financial assets? Also, just to be clear, I absolutely agree that commercial and investment banking should be separated. I’m just trying to get straight in my head what some of the implications are for the fact that reserve balances don’t seem to matter very much at all. It seems to me that if banks aren’t reserve constrained then all this talk by progressive economists about how the ZIRP policy also amounts to a huge subsidy for the big banks is so much nonsense. The title of Mr. Jayadev’s post was “The Gift from Borrowers to Banks.” In the article Mr. Jaydev explicitly claims that banks are using funds acquired cheaply from savers and eventually from the Fed to increase their lending, but at much higher rates:

“We can even make a very rough estimate of the value of this subsidy over the last year for the overall banking system. First, take the total stock of savings and small time deposits, overnight repos at commercial banks, and non-institutional money market accounts in the US, or in other words M2-M1. This works out to approximately $6.8 trillion on average over the period. Take the difference in the rate of interest on a one year CD at the beginning of 2008 (3.9%) and now (0.7%) as a rough proxy for the lowered short term borrowing rate for banks in short term markets (3.9%-0.7%=3.2%). By contrast, the rate of interest charged by commercial banks for car loans, personal loans and credit cards has hardly changed between early 2008 and February 2010, and has fallen in the first two cases by only about 0.5%. Even if we are generous and double that figure, and say that lending rates on average fell by 1%, this means a gift of (3.2%-1%)*6.8 trillion, or about $150 billion, from savers to banks.”

But if banks aren’t reserve constrained, then is there really any gift?

I guess the love affair with the multiplier theory is due to the illusion that it gives technocrats precise measure and control over credit growth. i.e, put reserve requirement at this level to get this much multiplier effect. The MMT alternative shows that they can never have this precise a control. What policymaker can tweak over-all credit demand, or system-wide bank capital adequacy, to arrive at the precise level of credit activity that the multiplier model alludes they can? Let alone that the policymaker can match the existing credit demander with the appropriate bank that has the capital, or appetite, for that sort of credit demander.

It’s probably similar to the early reluctance of medieval philosophers to abandon the earth-centric view of the universe. It just took out people’s comfort that the place they knew had to be the center of everything.

@Fed Up

Sorry, didn’t see your explanation when I posted my second comment. I think I understand what you mean by the subsidy, but I’m not sure what you describe is the what the economists I am reading have in mind. To put it a little more succinctly:

1) Bank A originates loan to Customer A

2) Customer A deposits loan in Bank B.

3) Bank A is now short reserves and because of capital requirement laws (maybe reserve requirement laws too?) it has to borrow from either another bank in the interbank market or, if the system overall is short reserves, from the federal reserve discount window. This involves paying a penalty rate. Not having to pay that rate is the “subsidy.”

I would also note that if Customer A simply deposited his/her loan at the same bank that originated the loan there would be no net change in reserves and hence no need to pay a penalty rate.

NKlein1553 said: \”I would also note that if Customer A simply deposited his/her loan at the same bank that originated the loan there would be no net change in reserves and hence no need to pay a penalty rate.\”

I think that is correct up to the \”and hence\”. I believe that assumes a zero reserve requirement.

I would not say no need to pay a penalty rate.

NKlein1553, I would say

1) Bank A originates loan to Customer A

1a) Customer A gets check (demand deposit) from Bank A

2) Customer A deposits check (demand deposit) in Bank B.

NKlein1553 said: “Bank A is now short reserves and because of capital requirement laws (maybe reserve requirement laws too?)”

I believe reserve requirements ONLY apply to reserves and capital requirements ONLY apply to capital.

NKlein1553 said: “This involves paying a penalty rate. Not having to pay that rate is the “subsidy.””

The way I read it is … the subsidy is NOT the penalty rate. The subsidy is the low rate paid on the deposit.

NKlein1553, this is from the worthwhile link above:

“Banks A and B start out the day “in balance” from all perspectives. Their assets equal their liabilities plus equity. And their world resembles Canada in that required reserves are zero. Both banks are at zero reserves.

There is one transaction to start. Bank A’s loan manager wants to make a loan of $ 10 million to customer X. (Think of X as a large blue chip corporation, or perhaps a wildly leveraged but fully prescient Canadian university professor betting the farm and all of his family’s and friends’ collateral on gold.) The loan manager does the credit analysis and approves it. Suppose the capital manager has an existing surplus capital position due to prior retained earnings that have not yet been allocated to risk assets. Assume that surplus capital is temporarily invested in treasury bills, which have a zero risk weight for capital purposes. The capital manager decides on the amount of capital required to support the loan risk, and allocates it accordingly as capital underpinning for the loan, in the event the loan transaction is completed. He allocates $ 1 million.

The reserve manager is notified of the pending loan drawdown. He assumes an outflow of reserves when the loan is draw down. He wants to attract an offsetting reserve inflow somehow in order to square his reserve account by the end of the day. Assume he has treasury bills in a liquid asset portfolio that represent the investment of capital funds that have so far been in surplus – i.e. not previously used to support risk assets. He plans to sell those bills for cash and redirect that internal capital to the new risk asset of $ 10 million. He needs additional funding of $ 9 million. He advises the deposit manager than he will require that funding.

The loan manager prices the loan. His inputs are the cost of capital, which he obtains from the capital manager, the benchmark cost of deposits, the cost required to cover expected credit losses, and other expenses assumed in pricing the loan such as related administrative salaries, etc. All of these costs can then be translated to an equivalent all in credit spread over a benchmark cost of funds. The loan is priced at that cost plus the credit spread.

I use “benchmark cost” here because the actual source of new funds in a “universal” bank can be wholesale or retail. New retail funds are “sold” internally into a central collection point at such a benchmark rate, providing retail bankers with a deposit spread to cover their own administrative and other costs. In the case of this simplified example, I’ll just assume now that the benchmark cost is the same as the actual wholesale cost of funds that the bank will end up paying in the market to fund this loan.

The loan manager goes to the deposit manager for a quote on the cost of funds – i.e. the expected wholesale deposit rate. The deposit manager may build in an additional small spread to allow for risk that the market price may “move” while the transaction is in progress.

The loan manager advises the customer of the all in cost based on the quoted market rate plus the credit spread. The customer accepts.

The loan manager completes the loan and advises the reserve manager and the deposit manager jointly.

Knowing that the lending transaction has been priced and accepted, the reserve manager then sells $ 1 million in treasury bills (previously funded by excess capital). The deposit manager puts out a bid for $ 9 million in additional funds.

Meanwhile, customer X has drawn down the $ 10 million in funds (in the form of a cheque drawn on A) and places them on deposit with his bank B.

Similar communications starting happening in bank B, and the reserve manager there is soon informed of the inflow of funds from bank A. He will now have an excess reserve position that he doesn’t want. At the same time he knows from market gathered information that bank A is looking for funds. He’s been informed by his loan manager that bank A continues to be a good credit risk. And his capital manager is comfortable in allocating capital to an interbank deposit transaction.

Away from the two transacting banks, the CB reserve manager observes that the market interest rate for interbank funds is quoted slightly above the interest rate he pays to banks for excess reserves. He’s satisfied with market conditions and leaves the system excess reserve setting alone.

The deposit manager in bank A has a bid out for $ 9 million in funds. Bank B’s reserve manager accepts that bid and places a $ 9 million interbank deposit with bank A.

Bank B also buys the $ 1 million in treasury bills sold by A through an investment dealer.

After the transaction, reserve accounts are flat again.

Had bank A been unable to attract funds from bank B for any reason in this example, A’s reserve manager could have gone to the central bank to borrow funds.

Additional internal activity within Bank B:

The balance sheet has increased with X’s $ 10 million deposit, $ 1 million in treasury bill assets, and the $ 9 million interbank loan to bank A. Bank B’s capital manager allocates $ 250,000 from his bank’s own pre-existing surplus capital to the interbank loan. This is a lower proportionate amount than Bank A allocated for X’s loan, because Bank A is itself a higher quality credit than A’s customer X. Again, B was in a surplus capital position prior to placing money with A. The assets in which this capital was previously invested (e.g. existing treasury bills) are now in a sense funded instead by $ 250,000 from the new deposit funding just raised. This is just internal book keeping reconciliation in order to keep track of the new allocation of risk capital and the corresponding depletion in surplus capital.

We assumed the CB reserve requirement was zero, so the new deposits for both banks have no impact on the CB’s strategy for the system reserve setting. In a system with positive reserve requirements, the CB would have supplied new reserves, perhaps through system repos with non bank dealers who took on new collateral purchased from non banks. The two banks would have competed for new deposits that had been created in conjunction with that reserve injection sequence, in order to attract their share of additional newly required reserves. And the process would compound from there. This is actually the textbook multiplier working in reverse, whereby the central bank responds to system deposit expansion by supplying any reserve requirement that follows from that. This is the actual mechanism when there are positive reserve requirements. The textbook description with the reverse causality is wrong. (See further discussion below.)”

Fed Up,

God created hyperlinks for a reason 🙂

Bill,

I wonder how CofFEE is treated within the department, and whether this crisis has opened more doors for you. Do your grad students graduate with an economics PhD?

A marxist friend of mine was a grad student in the econ department at Stanford and his advisor basically told him it would be better to leave for Harvard, where they are more open-minded. At that time — way back when — all his colleagues were studying game theory and other things that seemed really, really boring and involved a lot of square matrices. He told me that he felt unwelcome and disrespected, and I couldn’t imagine such a thing happening to a grad student, but now I have a better idea.

Bill it is ontologically not true that the currency notes are destroyed. Only the “unfit” ones are. In the US, the Fed keeps the notes which can be circulated again. The Financial Accounting Manual For Federal Reserve Banks that. I understand you mean that it can be considered that tax payments have gone into a tin shed, I just wanted to point the ontology.

Hmmm! Germany and France can’t let Greece default as they will then have to bailout their own banks again, as that’s where most Greek debt is. This is another facet of the bad, nay appalling, bank regulation we saw in those two countries, amongst others. So why not have G&F buy the debt from their banks and quietly tell (in a stage whisper) the Greeks that they’ll roll over the debt and interest when it’s due – in essence it’s debt forgiveness but with an accounting record. This is a horizontal transaction, so credit creation goes on but no high powered money. Meanwhile, Greece gradually moves its social security and taxation systems into line with their major creditors. What have I missed, apart from the impossible political problems?

Bill,

This is regarding your answer to Wally’s query (thanks Wally, I’ve had the same “block”).

Are you saying that gold standard systems really only become problematic when dealing with trade? Would they “work” in a pure domestic currency?

Ramanan says

In Sweden it works like this:

“The Riksbank (Central Bank) has two offices and via these supplies the banks with cash. The banks, or their agents, then distribute the cash to the retail trade and the general public.

The Riksbank does not determine how much cash is in circulation; instead this is determined by demand from the general public.

Swedish cash management has undergone major change in recent years. The new structure for cash management entered into full force in 2007. The banks and the bank depot companies are thus able to trade cash without the involvement of the Riksbank. Should a depot have a deficit of banknotes it is able to purchase notes from another depot that has a surplus. In this way there is now a market for trading in cash. The Riksbank’s role in this chain is solely to supply cash and to destroy banknotes and coins that can no longer be used. Three times a year the Riksbank will also accept any cash surplus. At present (January 2010) there are 12 bank-owned cash depots in operation.”

http://www.riksbank.se/templates/Page.aspx?id=24378

Fed Up,

The constraint is always from the demand side. So the theoretical multiplier because of capital adequacy doesn’t apply. It affects the interest rates though.

Useful to think of it dynamically. A privately held bank is safely satisfying capital adequacy. It makes loans and more loans. While doing so, it also receives interest payments. At the same time, there are interest costs on deposits, CDs. It also pays dividends to its owners and the rest goes as retained earnings. If the demand for loans increases, it may have to increase the loan rates. However, it is just temporary. As time passes, it receives higher interest payments. This puts the banks in a better capitalized position! Of course, in the recent crisis, there were all kinds of problems but the US Treasury says that banks still were well capitalized and TARP was merely to increase investors’ confidence. Of course I am talking here of the aggregated banking sector – one keeps hearing about banks shutting down.

Basil Moore’s book Horizontalists and Verticalists starts with (quoting with permission):

This book is out of print but I recommend Moore’s book Shaking The Invisible Hand which goes into details about banks and customers and gives sufficient emperical evidence that there is always a creditworthy demand shortage.

Dear Greg

No, the gold standard system even in a domestic setting would be dysfunctional. It means that economic growth is always tied to the stock of gold which may not be adequate to advance living standards. A gold standard is just an artificial policy rule and like all such rules which are divorced from the real context of the economy they will typically deliver sup-optimal outcomes – usually stagnation.

The point I was making to Wally and others is that to really understand the dynamics of a gold standard you have to allow specie flows. That requires a more complicated model than just the simple domestic economy model.

best wishes

bill

Hi all,

When this article is discussing the way the money suppy is not suppose to work, what so you mean on your last point when you say that the loan becomes so small it becomes zero. I don’t relly understand.

thanks,

Miffy

“The only thing that constrains the bank loan desks from expanding credit is a lack of credit-worthy applicants, which can originate from the supply side if banks adopt pessimistic assessments or the demand side if credit-worthy customers are loathe to seek loans.”

Bill,

So you believe that the APRA solvency and liquidity requirements have NO effect on bank lending?

Tobin says: “Unlike governments, bankers cannot create means of payment to finance their own purchases of goods and services. Bank-created “money” is a liability, which must be matched on the other side of the balance sheet. ”

I think I see what he is saying here, but it nevertheless seems to me that banks can, and do, purchase goods and services by creating deposit liabilities, which would appear to act as means of payment for such. If a bank credits your account for services rendered, then it has effectively paid you with something it has created de novo. The bank IOU (deposit liability) created, however, is, unlike government created IOUs, an IOU for something (government money) that the bank cannot itself create, which seems to be the distinction Tobin is making.

Food for thought.

The cost of unemployment is usually considered as the loss of income, skill and well being during unemployment. However, there is more than that. During unemployment there is a reduction/elimination in pension, employment insurance and retirement contributions. The result is lower benefits during retirement whose present value is a cost to be considered for a labor unit.

ParadigmShift,

Something I have always wondered is do banks \’create\’ money when paying interest on deposits and other liabilities? or do they pay it out of there existing pool of funds?

Gamma,

I believe that capital requirements are obviously in place and may throttle credit expansion in the short run.

“Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained”

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=9075

In regards to liquidity requirements – they are not exactly reserve requirements limiting lending and banks can always borrow money from the RBA (they obviously may prefer to seek deposits from elsewhere when this is cheaper).

This in fact will directly lead to M0 expansion as shown in the paper linked below.

As some people already know I am trying to get to the bottom of the money creation process and demonstrate in a clear way that “credit money” is destroyed when the debt is repaid.

(Dear Bill yes I know … please do not discard dynamic models, they can be fixed)

I found an interesting paper analysing the process of money creation explaining it from the accounting prespective in the context of “Property Economics” – tracing down the actual process of creating bank notes to the initial asset owned by the debtor issuing a “bill of exchange”

wwwm.htwk-leipzig.de/~m6bast/rvlmoney/UH-MonCreat.pdf

“The money which is needed for the fulfillment of the incurred contracts is created,

that means lent, on the basis of debt instruments which the contractors (here A, B

and the commercial bank) created themselves. So not the bank of issue discretionari-

ly determines the money supply (exogenous money supply [exogene Bestimmung der

Geldmenge]) but the proprietors determine the money supply out of their economic

activity reflected in the eligible assets, here the bill of exchange (endogenous determi-

nation of the money supply [endogene Bestimmung der Geldmenge]). The bank of is-

sue depends on the contractors’ readiness, willingness and creditworthiness to create

the eligible assets which back the issued banknotes.”

“whenever there seems to be elsehow no access to money credits, bills of exchange can be rediscounted

at the bank of issue in return for a credit of freshly issued money”

I spent 15 minutes Googling and I finally found the author and the master page to which the document was originally linked.

http://wwwm.htwk-leipzig.de/~m6bast/rvlmoney/rvlmoney.htm

Dr. Ulf Heinsohn (Fachhochschule für Wirtschaft Berlin)

To what extent is this consistent with MMT?

@mdm

Banks pay interest the same way they make loans and pay their worker’s salaries : by writing IOUs, which they call deposits. We then use those IOUs as if they were money.

Banks never ‘use’ a ‘stock of funds’ for anything. What they do do is, in effect, settle up all those IOUs with each other each night (no particular reason except bean-counting precision to do it every night; in theory it would work fine to do it once a year). This lead to reserves moving from one bank to another which is basically what reserves are for. If a bank is running out of reserves it needs to borrow money or raise capital.

Adam (ak),

The questions you are asking were considered and tackled by Marc Lavoie and Wynne Godley in their fantastic book Monetary Economics. See pages 400-404.

Banks make sure they are in a capitalized position by setting the lending rates, making projections about non-performing loans, targets for retained earnings and dividends. They maintain a target of capital adequacy and increase rates when they are below the target. However, this is temporary. While they start receiving interest payments, they will end up in a better capitalized position – allowing them to set the interest rates a bit lower than previous period(s). Of course, there are so many other things going on in the economy, so you may want to read the full dynamic model. In a more general case, banks may issue equities as well to increase their capital.

To get an idea of whats going on I refer you to Marc Lavoie’s chapter A Primer On Endogenous Credit-Money in this Google Books link pages 513 onward. You can find the draft version of the primer here

Quoting:

@begruntled,

I thought that would be the case. So in effect any form of bank spending will increase the money supply.

How does raising capital negate a bank running out of reserves? Is it because if it increases its capital it will be perceived as being a good credit risk and therefore seeing an inflow or reduction in outflow of deposits, meaning an increase in reserves or a lower rate of decreasing reserves, respectively?

Ramanan,

Thank you for the link.

Buying bank equities by the central bank is a nice little trick… Austrians would call it the ultimate moral hazard.

Believe me or not but I actually purchased the hardcopy of Monetary Economics book and I will read it fully in the right time – I only have had enough time to skim through it. I agree with the modeling approach and it’s not me who has a problem with credit destruction. My problem is to present arguments in such a way that there is no escape – to somebody who has no software engineering experience (as I know how to deal with the IT guys). This is difficult but possible. In the case of IT managers crashing the system a few times will usually do but with economists the task is a bit more complicated. I cannot crash the model it even if I know which element is incorrect.

I can tell you what’s wrong. Bank relending Bv/tauM doesn’t exist as the revolving fund in the Keynesian sense is maintained by constant process of new credit creation and old credit destruction. Bank relending is not a function of imaginary “bank reserves” as these simply do not exist in the real ledger. Banks cannot push credit on unsuspecting clients even if the cash vaults (on the assets side) are busting. Banks can lend to creditworthy clients and this depends on the capital (real assets) already owned by the debtor and on the future stream of income.

This is mentioned on page 51 of Monetary Economics “While the loan-granting activity created an efflux of money into the economy, the purchase of goods byh ouseholds creates a reflux – the destruction of money. Thus, any series of transactions can be conceived as the creation, circulation and destruction of money.”

The private money circuit is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7 and the model bears resemblance to the well-known to both of us continous-time models – with the exception of the absence of the infamous “bank relending” item. I believe that Godley and Lavoie are right. The models are developed further in the following chapters.

The real reason why I bother is because I think that only by combining the MMT (the Chartalist approach) with some elements taken from “debt-deflationists” we may finally get a dynamic macro model useful for experimenting with different policies. This will be useful to show to decision makers and academics why current European policies of maintaining low budget deficits are suicidal if private debt deleveraging takes place.

I do believe that the actual macroeconomic instability develops in the private sector due to excessive borrowing for speculation and overinvestment (I would not call it “saving”, it is much worse…). Government spending may help to plug the gap in the aggregate demand when the bubble bursts but the actual goal would be to make speculative bubbles less likely to develop. Are we condemned to blowing bubbles until we finally destroy our environment and run out of natural resources?

I have absolutely no problem with understanding the basics of MMT but the reason why I insist so much on including “debt-deflationist” elements in the models is that certain critically important phenomena are removed from the picture if we operate at the highest level of macro modelling. In regards to “Monetary Economics” the book contains one prediction which turned out to be false. On page 27 it is stated that: ” if equity prices (or housing prices) were to fall below the value at which they were purchased with the help of loans taken for pure speculative purposes (…) the net worth of households taken overall could become negative (…) In the case of American households, this is not likely to happen, based on the figures presented in Table 2.1 (…) Loans represent less than 20% of net worth”

Well it did happen – not for all the households of course. It also happened in other countries. I believe it is likely to happen in Australia as well unless some very onerous conditions are met all the time or the framework within which our economy operates changes dramatically in the direction advocated by the MMT scholars (well we currently have only one – in Newcastle…)

This is unlikely so I think that the “debt-deflationist” intuitions even if expressed with minor mistakes still have a lot of value. Let’s wait a few months or a year and see what happens when the real estate bubble in China bursts…

An alternative (and complementary) modelling approach would involve distributed agents. What is really sad I can only spend less that an hour a day studying as I have to work full time.

Hi ak,

Actually that was what TARP was! However, it was the US Treasury purchasing newly issued equities instead of the Federal Reserve. So Marc Lavoie knew about a way to prevent the banking system collapsing. Yes – there was so much drama associated with TARP. In fact it would have been better if the Fed had done the TARP instead of the Treasury doing it.

Btw, your observation on net worth of households going negative because of fall in equity prices because of them having bought them with loans didn’t happen. The household net worth was positive all along, though fell during the recession. Wynne Godley knows the US economy too well!

You can see some debt-deflation happening in the G&L models – Page 239.

Actually, I don’t know the bank relending part you and Steve talk about well. My understanding is what I mentioned in the previous comment.

Ramanan,

Thank your for the response.

Let me clarify, I only stated that some households got into negative equity (and were unable to service the current debt payments) but the number of households affected was large enough to affect the whole economy.

“About 11 million households, or a fifth of those with mortgages, are in this position, known as being underwater. Some of these borrowers refinanced their houses during the boom and took cash out, leaving them vulnerable when prices declined. Others simply had the misfortune to buy at the peak.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/26/business/26housing.html

I understand what Marc Lavoie ment when the book was written – he referred to the whole sector. Technically he was right. It is not an error it is just a feature of the model.

Regarding TARP itself it remains highly controversial to me especially its capital infusion component.

The real reason why I bother is because I think that only by combining the MMT (the Chartalist approach) with some elements taken from “debt-deflationists” we may finally get a dynamic macro model useful for experimenting with different policies. This will be useful to show to decision makers and academics why current European policies of maintaining low budget deficits are suicidal if private debt deleveraging takes place.

Adam,. my sense is that you are on the right track. It seems to me that MMT principles, Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis (late-stage Ponzi finance aka fraud), and debt-deflation (mortgage foreclosures continue and commercial RE is now threatened, resulting in ongoing bank failures) have to be combined in describing the still unfolding financial crisis in the US. That’s the way I’ve been able to make sense of it anyway.

Not only does the bad macro need to be addressed, but also Ponzi finance and the moral hazard enabling it. Minsky’s insights into the long financial cycle do not seem to be considered at present any more than Post Keynesian demand side macro. So most of the mainstream debate is going on in la-la land, and the public is being badly informed by the media, which doesn’t have a clue. As a consequence we seem headed for 1937 redux at minimum, and at worst the world could conceivably stumble into Great Depression II.

A logically compelling model would be invaluable in putting these points across. But so far, few are willing to even look at the accounting identities that apply to sectoral balances. Instead, they assume the impossible, namely, that government and nongovernment can be in surplus over the same period.

“It seems to me that MMT principles, Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis (late-stage Ponzi finance aka fraud), and debt-deflation (mortgage foreclosures continue and commercial RE is now threatened, resulting in ongoing bank failures) have to be combined in describing the still unfolding financial crisis in the US.”

MMT already DOES incorporate Minsky, debt deflation, horizontalism, the circuit, and so forth. I don’t know how many times I’ve said this, but it would seem that anyone regularly reading Billy Blog, KC Blog, Mosler, etc, should know this simply from the content therein. Similarly, it would seem anyone looking at MMT research published at CofFEE, CFEPS, Levy, etc., could see this.

It is quite true, at the same time, that MMT’ers have generally not pursued developing dynamic models of the differential equation variety. If the incorporation of vertical money, horizontal money, Minsky, debt deflation, etc., into dynamic/diff eq models is what is meant by “integrating MMT with . . . ,” then that’s fine, if imprecisely stated.

But, again, it’s important to recognize that MMT doesn’t leave out horizontal, Minsky, debt deflation, etc. Anyone who thinks otherwise has a very limited exposure to MMT, or is at least using an incorrect definition of what MMT actually is.

Best,

Scott

Hi Bill,

I was a student at newcastle during the pogrom of heterodox ideas from the undergrad program, and continue to be pretty disenfranchised by what happened there.

Fortunately some of the staff that were there then highlighted the PKE and institutionalist alternatives….!

All the best.

Scott’s post said: “But, again, it’s important to recognize that MMT doesn’t leave out horizontal, Minsky, debt deflation, etc. Anyone who thinks otherwise has a very limited exposure to MMT, or is at least using an incorrect definition of what MMT actually is.”

What does MMT have to say about wealth/income inequality, the time changes between spending and earning that debt allows, and changes in retirement dates?

Scott Fullwiler,

You are right you do need to integrate into your analysis the dynamic paradigm such as feedback loops since the static accounting balances and matrices used in your framework does not allow the behavioral hypotheses of your thesis to be presented fully. The FIH, Financial Fragility and the Deflation Process are a good starting point. You need to add complexity and imperfection in your parameters and the entropies that impact the feedback loop and make it explosive.

Scott,

I feel your pain.

Hope somebody feels mine – with respect to the difference between the idea of a constraint and the idea of a binding constraint (as in capital).

Hi Panayotis,

I don’t disagree. But recognize that there are only about 2-3 handfulls of scholars doing MMT academic research, and the vast majority of those only finished graduate school within the last decade. So please forgive us if we haven’t already completed every type of research inquiry that everyone would like to see regarding MMT. That said, I think MMT research output has been quite impressive overall, again, particularly given the limited numbers of scholars.

Best,

Scott

I feel it, JKH. It never ends, does it?

@Scott, No, it never ends. Ever read the myth of Sisyphus?

@Bill Thanks for the hat tip!

Scott, I am aware that MMT does include both the financial instability hypothesis and debt deflation in its analysis. What I was implying is this. The popular understanding of MMT that is now growing focuses on the vertical aspect of the vertical-horizontal relationship, in that much of the discussion centers around government fiscal policy and CB monetary operations. As a result many people do not realize that as a comprehensive theory MMT includes a lot more. I would say that this applies also to the JG, which many people don’t necessarily associate with MMT either.

Randy’s posts at Economic Perspectives are principal “popularizations” of Minskian ideas, but there is nothing that would lead someone to associate them with “MMT” either. Unless people get into the academic stuff, the comprehensive nature of the macro theory isn’t very visible to most people.