I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Lost in a macroeconomics textbook again

Today’s Australian newspaper, sadly our national daily carries a story – Stimulating our way into trouble – by Griffith University professor (and ex-federal treasury official) Tony Makin. I pity the students who have to study with him. The article continues the News Limited campaign against the government stimulus package and demonstrates the extent that is prepared to use the services of so-called experts (that is, titled mainstream economists) who seem prepared to grossly mislead the readership to advance their ideological strategy. Whatever it takes seems to be the strategy. Anyway, once again the mainstream macroeconomics textbook is called upon to make policy statements.

Tony Makin is already in the running for the billy blog worst Op-Ed column of 2009 award which I will announce at the end of the year. I think this article reinforces his hold on that award. Possibly the worst article of all time.

For a professional economist such as myself the Makin article is very funny – because it is so bad – sort of like those old movies – such as Santa Claus conquers the Martians, which is a particular favourite. But the message it provides is potent to those who are wavering on the issue and do not understand the technical framework that Makin is using as an authority for his parlous argument.

In short, this sort of spurious reasoning sounds reasonable, is highly dangerous but also spurious to the core.

Makin begins by noting that:

SINCE late last year numerous contributors to this page, me included, have argued that the Keynesian spend and borrow response to the economic downturn embraced by the federal and state governments has been seriously flawed in theory and practice.

Yes a veritable cacophony of shrill conservatives who haunt the pages of The Australia and who are wheeled out on a daily basis to scare the readership who, unfortunately, do not know better. This is not a newspaper that tolerates broad perspective.

Anyway, Makin decides to approach this from a theoretical basis saying that:

The 23 per cent increase in the current account deficit in the September quarter arising from a fall in exports and rise in imports provides direct evidence of this.

To understand why, we need only invoke undergraduate textbook theory of how fiscal policy operates in an open economy with a floating exchange rate.

This theory tells us that a growing budget deficit due to increased government spending of the kind we have seen puts upward pressure on domestic interest rates, all other things being equal.

First, lets be clear on what happened to the external accounts in the September quarter. It is true that the Current Account balance went from a deficit of -13,133 million AUD to -16,183 million in the September quarter a reduction of 23 per cent.

Almost all of the change was driven by the balance on goods and services. The decline in net exports “This is expected to detract 1.8 percentage points from growth in the September quarter 2009 volume measure of GDP” (Source).

The ABS data tells us that “the net goods deficit rose $3,847m to $4,767m” and the “net services deficit rose $377m to $641m”. Exports fell by 6 per cent while imports rose by 2 per cent.

In terms of the rising imports, capital goods rose by 6 per cent and accounted for more than 66 per cent of the rise in imports. A 3 per cent rise in intermediate and other merchandise goods accounted for a smaller proportion. Capital goods and intermediate gods reflect the growing investment that is now appearing in the Australian economy.

The change in consumption imports accounted for only 5 per cent of the total rise in imports in the September quarter.

So that looks like an economy that is dependent on imported capital equipment which is in the early stages of an investment boom. The declining exports reflect soft conditions in world markets which are of-course exogenous to Australia.

Then consider Makin’s call to authority – the “undergraduate textbook theory of how fiscal policy operates in an open economy with a floating exchange rate”. The theory he is alluding to tells you very little about the way the real world actually operates.

To see this it is best to first rehearse his argument that fiscal policy expansion drives up interest rates.

Need I say it but using the same textbook theory a rise in private investment spending or net exports will have exactly the same impact on interest rates. That is, any spending growth would deliver the same outcome.

Anyway, in attempting to establish his proposition, Makin says that interest rates rise:

… because increased government spending increases the overall demand for money in the economy which, for a given supply of money as determined by the Reserve Bank of Australia, tends to raise domestic interest rates above foreign interest rates.

This is an extraordinary piece of cheek.

The mainstream theory of money and monetary policy that Makin is appealing to asserts that the money supply (volume) is determined exogenously by the central bank. That is, they have the capacity to set this volume independent of the market. The monetarist portfolio approach claims that the money supply will reflect the central bank injection of high-powered (base) money and the preferences of private agents to hold that money. This is the so-called money multiplier.

So the central bank is alleged to exploit this multiplier (based on private portfolio preferences for cash and the reserve ratio of banks) and manipulate its control over base money to control the money supply.

To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in MMT. When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

While there have been many contributors to the literature on endogenous money, my favourite work is the evolving writing of Marc Lavoie, who is at the University of Ottawa and who I have a lot of time for. The core articles are:

- Lavoie, M. (1984) ‘The endogeneous flow of credit and the Post Keynesian theory of money’, Journal of Economic Issues, 18, 771-797.

- Lavoie, M. (1992) Foundations of Post-Keynesian Economic Analysis, Aldershot, Edward Elgar.

- Lavoie, M. (1996) ‘Horizontalism, structuralism, liquidity preference and the principle of increasing risk’, Scottish

Journal of Political Economy, 43, 275-300. - Marc Lavoie’s excellent 2001 working paper Endogenous Money in a Coherent Stock-Flow Framework also provides a free way of getting into some of the later evolution of the work. But this paper is not easy.

Lavoie wrote in 1984 (page 774):

When entrepreneurs determine the effective demand, they must plan the level of production, prices, distributed dividends, and the average wage rate. Any production in a modern or in an “entrepreneur” economy is of a monetary nature and must involve some monetary outlays. When production is at a stationary level, it can be assumed that firms have at their disposal sufficient cash to finance their outlays. This working capital, in the aggregate, constitutes credits that have never been repaid. When firms want to increase their outlays, however, they clearly have to obtain extended credit lines or else additional loans from the banks. These flows of credit then reappear as deposits on the liability side of the balance sheets of banks when firms use these loans to remunerate their factors of production.

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply. As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans.

The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves. Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

With the season approaching, I recalled a lovely 1970 quote by Nicholas Kaldor (in ‘The New Monetarism’, Lloyds Bank Review, July, 1-17) about what would happen if the central bank tried to restrict credit:

There would be chaos for a few days, but soon all kinds of money substitutes would spring up: credit cards, promissory notes, etc., issued by firms or financial institutes which would circulate in the same way as bank notes … a complete surrogate money-system and payments-system would be established, which would exist side by side with “official money”.

There are all sorts of disputes in this literature – some arcane, most interesting – as to whether the money supply is infinitely elastic (that is, not sensitive to the interest rate) or not. The nuances in the debate do not alter the fundamental insight. The central bank does not control the money supply.

The conclusion is clear: central banks use short-term interest rates as their usual policy instrument and largely ignore the monetary aggregates that are endogenously determined. These aggregates provide very little information that the evolution of GDP and employment growth provide anyway. And the real aggregates are what policy is concerned with anyway.

You may like to read what the RBA says about its monetary policy role. You will read nothing at all about how there is a “given supply of money” which the RBA determines. A visit to any central bank WWW site will tell you a similar story in a multitude of languages.

In terms of the implementation of monetary policy, the RBA says that:

From day to day, the Bank’s Domestic Markets Department has the task of maintaining conditions in the money market so as to keep the cash rate at or near an operating target decided by the Board. The cash rate is the rate charged on overnight loans between financial intermediaries. It has a powerful influence on other interest rates and forms the base on which the structure of interest rates in the economy is built … Changes in monetary policy mean a change in the operating target for the cash rate, and hence a shift in the interest rate structure prevailing in the financial system … The Reserve Bank uses its domestic market operations (sometimes called ‘open market operations’) to keep the cash rate as close as possible to the target set by the Board, by managing the supply of funds available to banks in the money market.

The cash rate is determined in the money market as a result of the interaction of demand for and supply of overnight funds. The Reserve Bank’s ability to pursue successfully a target for the cash rate stems from its control over the supply of funds which banks use to settle transactions among themselves. These are called exchange settlement funds, after the accounts at the Reserve Bank in which banks hold these funds.

If the Reserve Bank supplies more exchange settlement funds than the commercial banks wish to hold, the banks will try to shed funds by lending more in the cash market, resulting in a tendency for the cash rate to fall. Conversely, if the Reserve Bank supplies less than banks wish to hold, they will respond by trying to borrow more in the cash market to build up their holdings of exchange settlement funds; in the process, they will bid up the cash rate.

Note that this is a discussion about manipulating bank reserves (in Australian parlance “exchange settlement funds”). Note also the last paragraph they clearly tell us that the “cash position” of the monetary system (that is, the volume of bank reserves) are critical for determining the movement in the cash rate and the RBA’s ability to maintain control over it.

Notice that when there are excess reserves the banks “try to shed funds” and this has a “tendency for the cash rate to fall” (and vice versa). Modern monetary theory (MMT) tells us that net government spending adds to bank reserves which create the same tendency for the cash rate to fall. That tendency is arrested by liability management operations conducted by the central bank.

Please read my billogy of blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for more discussion on this point.

[Editor’s note: three themed blogs is a Trilogy but I couldn’t find an expression for two themed blogs and my very literate partner wasn’t able to enlighten me. So given bi = 2 and I am bill – I am thus calling my recent series on bank reserves a billogy].

You will note that in MMT there is very little spoken about the money supply. In an endogenous money world there is very little meaning in the aggregate.

The central bank does publish data on various measures of “money”. They publish data for:

- Currency – Private non-bank sector’s holdings of notes and coins.

- Current deposits with banks (which exclude Australian and State Government and inter-bank deposits).

- The M1 measure – Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector.

- The M3 measure – M1 plus all other ADI deposits of the private non-ADI sector. So a broader measure than M1.

- Broad money – M3 plus non-deposit borrowings from the private sector by AFIs, less the holdings of currency and bank deposits by RFCs and cash management trusts.

- Money base – Holdings of notes and coins by the private sector, plus deposits of banks with the Reserve Bank and other Reserve Bank liabilities to the private non-bank sector.

Note that ADI are Australian deposit-taking institutions; AFI are Australian financial intermediaries; and the RFCs are Registered Financial Corporations. Here is the RBA’s excellent glossary for future reference.

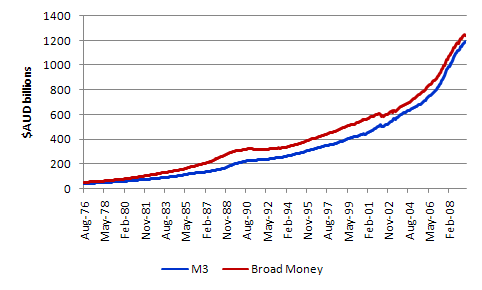

The following graph shows the monthly evolution of M3 and Broad Money in Australia since August 1976 up until October 2009. While I don’t hold much store in these aggregates, the same cannot be said for the textbook models that Makin is trying to suggest to his readers are important. There is no way one could argue that the money supply is fixed even over a short period.

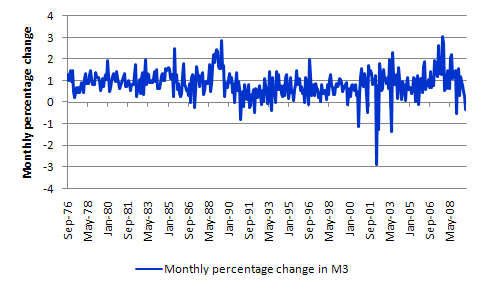

The next graph just shows the monthly percentage changes in M3 for Australia (%). The growth rate is variable and reflects the various factors that endogenous growth theorists have identified as being influential in driving the credit cycle.

Makin’s depiction of the monetary system is clearly just plain wrong! And he holds himself out as a professor of economics. That is just a disgrace.

So having dealt with that we consider the rest of Makin’s argument which attempts to tie interest rate rises to our current account position.

It is clear that the budget deficits are not driving the rising interest rates. To claim this you would have witnessed significantly rising and high interest rates in Japan in the 1990s and US interest rates should be rising more quickly than Australia’s given its deficit is significantly larger as a percentage of GDP.

The RBA set the interest rate. It has a pavlovian rule that tells it to push up rates if it expects inflation to emerge. At present it is saying the cash rate is below its neutral rate – so according to their logic – stimulatory. It is merely (within its own logic) moving the rate slowly up to its neutral position again. Please read this selection of blogs – Search string for neutral interest rates – for more discussion on this point.

While previous blogs I have written (see search string above) criticise this concept, the RBA is not tightening rates because there is a shortage of money as asserted by Makin. They are being defensive in terms of their charter to fight inflation first.

Anyway, Makin then says:

Rising interest rates in turn induce foreign capital inflow and strengthen the exchange rate. This worsens Australia’s competitiveness in relation to its trading partners, resulting in lower exports and higher imports.

The explanation of our appreciating exchange rate is significantly more complex than this. For a start, any terms of trade effects on trade are lagged and would not be showing up in the September quarter data.

Further, a significant driver of our exchange rate are the commodity prices (particularly base metals) which have showed some signs of recovery in recent months (Source).

Our trading prospects are also heavily dependent on the state of the world economy and this has reduced our net export contribution (an income effect) more significantly than the relative price effects arising from exchange rate changes (which are yet to be felt).

But as I noted above, the rising imports are a sign that investment is picking up strongly which suggests a positive reaction to the fiscal stimulus.

Makin then reinvents a further myth:

… the twin deficits phenomenon is back: the consolidated budget deficit of the federal and state governments appears to be causing higher trade and current account deficits.

“Appears to be”. On what evidence would we be able to conclude that? Makin certainly provides none. How would he explain the rising current account deficit when the federal budget was in surplus for 10 out of 11 years between 1996 and 2007?

While there is a clear relationship between these national account balances (the so-called sectoral balances) the causality is tricky. Certainly, a fiscal expansion will stimulate aggregate demand which will increase output growth and some of the demand will leak into imports. The fact that the substantial driver of import growth is investment demand (capacity building) would suggest that the fiscal expansion is not leading exclusively to a binge on imported K-Mart plastic junk.

But given Australia’s external account (current account) is typically in deficit, then the only way the economy can continue to growth (and recover from the slump) as the private domestic sector increases its saving ratio to restore the precarious nature of household balance sheets following the credit binge (induced, in part, by the federal surpluses), is via federal deficits.

That is the causality – slump in private spending, GDP contraction, automatic stabilisers drive the budget deficit up, government reacts by discretionary net spending to underwrite GDP growth, income rises and so do imports. That seems like a good story to me.

Makin then gets desperate:

… ultimately, foreign funding of the current account deficit has to be linked to highly productive investment spending. Otherwise, foreign investors will take fright, the current account deficit will become unsustainable, and the nation’s credit-rating will be downgraded, leading to a further spike in interest rates.

So we are left with the scare mongering. Australia has run large deficits regularly during the fixed exchange rate period and the fiat currency period. We have never had an unsustainable current account – whatever that is nor have we ever received a credit-rating downgrade – as if that would matter anyway.

It is true that the rising exchange rate will make it harder for manufacturing to compete – but that has nothing to do with the fiscal position. It reflects our very unbalanced export sector where mining, agriculture and industrial traded-goods face very different world demand conditions. Of late, our minerals demand has been huge and this is putting an exchange rate squeeze on the other traded-goods activities.

And further, if foreign investors really take fright what will happen. According to Makin’s theory this would cause our exchange rate to depreciate which should satisfy him anyway.

Conclusion

A ridiculous piece of commentary. But it gave me the chance to talk a bit about monetary aggregates and endogenous money theory and acknowledge the work of Marc Lavoie.

Thanks again Bill for a very timely piece.

At this point in my MMT education I am pondering a lot of things .Its amazing how often your piece gets at what I’m thinking about.

My real interest lately has been how the “gap” between well meaning conventional economists like Mr Thoma or Mr Krugman and the MMTers can be bridged. You point out very well where their thinking is poisoned by so much gold standard like talk. For someone like me who never studied economics I have no such baggage but I imagine that old notions are hard to get rid of. In talking about money supply it seems clear to me that the traditionalists still view it as limited(and under control of CB) and hence thats why they see spending from one sector (govt) as cramping the other. You called this a hydraulic view I believe in one of your posts.

It seems that one way to understand the fuzziness in the thinking of the nonMMTers is when they talk about inflation and interest rates. They talk like inflation will be brought on by a rise in the interest rates, when in fact it seems by my understanding of your last 3 posts that a rise in interest rates would only be a result(not necessary but possible) of inflation, not an automatic result but a response by CBs. Raising interest rates may be a policy tool but not a necessary one. Do I have this right?

Because the supply of money is never constrained in the aggregate there is never “automatic” changes in interest rates. All changes are determined and preconsidered. Am I on track here regarding some basic facts? This seems a seminal point in the whole discussion.

It seems to me as well we are overly worried about inflation. The only inflationary time (that any one points to any way) is the 70s, in the US. That as I understand it, was a pretty clear example of oil prices rising, from a supply contraction (or pretend contraction) and increasing the price of everything dependent on oil, which is pretty much everything. No fancy theories of money supply, govt spending and interest rates needed there. Pretty straightforward case it seems.

Professor Mitchell,

Your quote from Kaldor reminded me of the Irish banking strike of 1970, which I think reinforces

this with real-world evidence (the following is Prof Bob Murphy’s redaction of the work of Antoin Murphy):

“We would expect the closure of banks severely to disrupt the functioning of an economy. The Irish experience in 1970

(studied by the Irish economist Antoin Murphy) provides an interesting counterexample. In

that year, a major strike closed all Irish banks for a period of six and a half months. All the

indications from the start, moreover, were that this would be a long closure. As a

consequence of the strike, the public lost direct access to about 85 percent of the money

supply (M2). Irish currency still circulated, of course, British currency was also freely

accepted in Ireland, and some North American and merchant (commercial) banks provided

banking facilities. Increases in Irish and British currency and in deposits in these banks,

however, accounted for less than 10 percent of M2.

Somewhat remarkably, checks on the closed banks continued to be the main medium of

exchange during the dispute. Despite the increased risk of default, individuals continued to

be willing to accept personal and other checks. Murphy summarizes the situation as follows:

“a highly personalized credit system without any definite time horizon for the eventual

clearance of debits and credits substituted for the existing institutionalized banking

system.”

According to Antoin Murphy, it was the small size of the Irish economy (the population of

Ireland was about 3 million at that time) and the high degree of personal contact that

allowed the system to function. Stores and pubs took over some of the functions of the bank-

ing system. “It appears that the managers of these retail outlets and public houses had a

high degree of information about their customers-one does not after all serve drink to

someone for years without discovering something of his liquid resources. This information

enabled them to provide commodities and currency for their customers against undated

trade credit. Public houses and shops emerged as a substitute banking system.”

Presumably as a result of this spontaneous alternative banking system, economic

activity in Ireland was not substantially affected by the banking strike. Detrended retail

sales did not differ much on a month-by-month basis from average levels in the absence of

banking disputes, and a central bank survey concluded that the Irish economy continued to

grow over the period (although the growth rate fell).

People can laugh all they want about people like Tony Makin. The sad fact is that people like him are determining what is taught in universities. Those students then move on to either private or public sector employment and the army of fools keeps on growing.

That these people don’t know an endogenous variable from an exogenous variable is of little importance because if the emperor say’s he’s wearing the coat then the majority of people are going to say that they see the coat regardless of whether they can or not.

Mr.Mitchell: I noted some time ago on your blog that I was auditing Marc Lavoie’s post-keynesian economics course at the University of Ottawa beginning in September. It was great! The only bad thing was that it lasted just one term, endng in early December. Marc is a terrific pedagogue and managed to explain quite complicated models and ideas very clearly and in an interesting, real-world related way. If only my original masters of economics courses had been taught that way 20 years ago…

Anyway, since the topic over the last few days has been university textbooks, I thought I would put in a plug for Marc Lavoie’s introductory Macro textbook, entitled Macroeconomics – Principles and Policy, First Canadian Editon, Nelson Education 2010. (www.nelson.com) The Authors are William J. Baumol, Alan S. Blinder, Marc Lavoie, Mario Seccareccia. It’s really an excellent book. It clearly explains the operating of the monetary system: endogenous money, the role of the Bank of Canada, the chartered banks, the determination of the overnight rate, etc. It also discusses how government budget deficits must equal the current account balance plus private sector financial savings. It is an introductory book so cannot deal with everything but compared to the alternatives it is in an entirely different league. Out of curiosity I looked at Mankiw (your favourite!) as well as Blanchard – sad, sad, sad.

He also has a short book entitled Introduction to Post-Keynesian Economics (Palgrave MacMillan:2009) of which he is the sole author and which is excellent as well – it was the textbook we used in the course.

Your blog is great and I’m trying to spread the word.

The 2001 Marc Lavoie article mentioned above has interesting things to say about endogeneity, loans creating deposits etc.: that it cannot be otherwise. I like such arguments.

I will second Keith’s endorsement of the text by Marc and Mario. It’s truly the only one I’ve seen that gets monetary operations correct. If I taught in Canada, I would definitely use it, though the material on banking might apply most anywhere, actually. And besides being excellent economists, they are two of the nicest people anyone would want to meet.

Bill/Scott,

Was wondering about this post.

Verticalists is the neoclassical position and horizontalists recognize the endogenous nature of money, though endogeneity when one considers the government sector is seen/recognized by an even lesser crowd. There are even the so called structuralists who argue that interest rates rise with the supply of money since increase in loans increases the cost of capital and reserves. This can be dismissed by two arguments

(a) more loans may increase the loan rates briefly, but interest payments and undistributed profits brings back the loan rates

(b) emperically the money supply keeps increasing but interest rates dont keep increasing

plus the government spending percolates and some of it provides bank capital and more reserves. So its best to represent interest rate vs money supply graph as horizontal.

Securitization also makes “money supply” irrelevant. A bank creates deposits by lending – in the process increasing the “money supply”. However, securitization reduces deposits and money supply in exchange for securities. Is that correct ?