Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – June 11-12, 2016 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

A sovereign national government, that is, one that issues its own floating currency faces no solvency risk with respect to the debt it issues.

The answer is False.

The answer would be true if the sentence had added (to the debt it issues) … in its own currency. The national government can always service its debts so long as these are denominated in domestic currency.

It also makes no significant difference for solvency whether the debt is held domestically or by foreign holders because it is serviced in the same manner in either case – by crediting bank accounts.

The situation changes when the government issues debt in a foreign-currency. Given it does not issue that currency then it is in the same situation as a private holder of foreign-currency denominated debt.

Private sector debt obligations have to be serviced out of income, asset sales, or by further borrowing. This is why long-term servicing is enhanced by productive investments and by keeping the interest rate below the overall growth rate.

Private sector debts are always subject to default risk – and should they be used to fund unwise investments, or if the interest rate is too high, private bankruptcies are the “market solution”.

Only if the domestic government intervenes to take on the private sector debts does this then become a government problem. Again, however, so long as the debts are in domestic currency (and even if they are not, government can impose this condition before it takes over private debts), government can always service all domestic currency debt.

The solvency risk the private sector faces on all debt is inherited by the national government if it takes on foreign-currency denominated debt. In those circumstances it must have foreign exchange reserves to allow it to make the necessary repayments to the creditors. In times when the economy is strong and foreigners are demanding the exports of the nation, then getting access to foreign reserves is not an issue.

But when the external sector weakens the economy may find it hard accumulating foreign currency reserves and once it exhausts its stock, the risk of national government insolvency becomes real.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

- Debt is not debt

- The deficit and debt debate

- Debt and deficits again!

Question 2:

One important lesson to be drawn from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which is overlooked in the public call for austerity programs, is that when economic growth resumes, the automatic stabilisers work in a counter-cyclical fashion to ensure that the government fiscal balance returns to its appropriate level.

The answer is False.

The factual statement in the proposition is that the automatic stabilisers do operate in a counter-cyclical fashion when economic growth resumes. This is because tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this increases when there is an economic slowdown.

The question is false though because this process while important may not ensure that the government fiscal balance returns to its appropriate level.

The automatic stabilisers just push the fiscal balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit when GDP growth declines and vice versa when GDP growth increases. These movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

We also measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the fiscal balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

This decomposition provides (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical fiscal balances. The fiscal components are adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal balance is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal balance into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

In some of the blogs listed below I go into the measurement issues involved in this decomposition in more detail. However for this question it these issues are less important to discuss.

The point is that structural fiscal balance has to be sufficient to ensure there is full employment. The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose.

In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

Given the non-government sector will typically desire to net save (accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue) over the course of a business cycle this means that there will be, on average, a spending gap over the course of the same cycle that can only be filled by the national government. There is no escaping that.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap. However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a fiscal surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the fiscal outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs). But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The fiscal balance will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment – which I define as 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

So it will not always be the case that the dynamics of the automatic stabilisers will leave a structural deficit sufficient to finance the saving desire of the non-government sector at an output level consistent with full utilisation of resources.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 3:

It is claimed that Eurozone Member States need to rely on internal devaluation. Austerity programs thus aim to deflate nominal wages and prices in order to restore international competitiveness. Which of the following propositions must also follow according to this logic?

(a) If wages and prices fall at the same rate, then labour productivity has to rise and employment remain constant or grow.

(b) If wages and prices fall at the same rate, then labour productivity has to rise and employment must grow.

(c) If wages and prices fall at the same rate, then labour productivity has to rise and what happens to employment is irrelevant.

(d) None of the above.

The correct answer is If wages and prices fall at the same rate, then labour productivity has to rise and what happens to employment is irrelevant.

The EMU countries cannot improve their international competitiveness by exchange rate depreciation, which is the option always available to a fully sovereign nation issuing its own currency and floating it in foreign exchange markets.

Thus, to improve their international competitiveness, the EMU countries have to engage in “internal devaluation” which means they have to cut real unit labour costs – which are the real cost of producing goods and services. Governments setting out on this policy path have to engineer cuts in the wage and price levels (the latter following the former as unit costs fall).

But the question demonstrates that it takes more than just a nominal deflation. The strategy hinges on whether you can also engineer productivity growth (typically).

So given the assumption (wage and prices falling at the same rate), the correct answer is:

If wages and prices fall at the same rate, then labour productivity has to rise and what happens to employment is irrelevant.

Some explanatory notes to accompany the analysis that follows:

- Employment is measured in persons (averaged over the period).

- Labour productivity is the units of output per person employment per period.

- The wage and price level are in nominal units; the real wage is the wage level divided by the price level and tells us the real purchasing power of that nominal wage level.

- The wage bill is employment times the wage level and is the total labour costs in production for each period.

- Real GDP is thus employment times labour productivity and represents a flow of actual output per period; Nominal GDP is Real GDP at market value – that is, multiplied by the price level. So real GDP can grow while nominal GDP can fall if the price level is deflating and productivity growth and/or employment growth is positive.

- The wage share is the share of total wages in nominal GDP and is thus a guide to the distribution of national income between wages and profits.

- Unit labour costs are in nominal terms and are calculated as total labour costs divided by nominal GDP. So they tell you what each unit of output is costing in labour outlays; Real unit labour costs just divide this by the price level to give a real measure of what each unit of output is costing. RULC is also the ratio of the real wage to labour productivity and through algebra I would be able to show you (trust me) that it is equivalent to the Wage share measure (although I have expressed the latter in percentage terms and left the RULC measure in raw units).

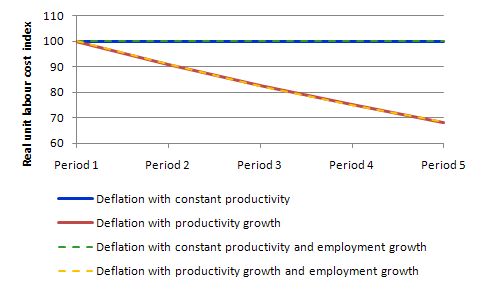

The following table models the constant and growing productivity cases but holds employment constant for five periods. We assume that the nominal wage and the price level deflate by 10 per cent per period over Period 2 to 5. In the productivity growth case, we assume it grows by 10 per cent per period over Period 2 to 5.

It is quite clear that under the assumptions employed, RULC cannot fall without productivity growth. The only other way to accomplish this is to ensure that nominal wages fall faster than the price level falls. In the historical debate, this was a major contention between Keynes and Pigou (an economist in the neo-classical tradition who best represented the so-called “British Treasury View” in the 1930s. The Treasury View thought the cure to the Great Depression was to cut the real wage because according to their erroneous logic, unemployment could only occur if the real wage was too high.

Keynes argued that if you tried to cut nominal wages as a way of cutting the real wage (given there is no such thing as a real wage that policy can directly manipulate), firms will be forced by competition to cut prices to because unit labour costs would be lower. He hypothesised that there is no reason not to believe that the rate of deflation in nominal wage and price level would be similar and so the real wage would be constant over the period of the deflation. So that is the operating assumption here.

The following table models the constant and growing productivity cases as above but allows employment to grow by 10 per cent per period. All four scenarios in the Table are them modelled in the following graph with the Real Unit Labour Costs converted into index number form equal to 100 in Period 1. As you can see what happens to employment makes no difference at all.

I could have also modelled employment falling with the same results.

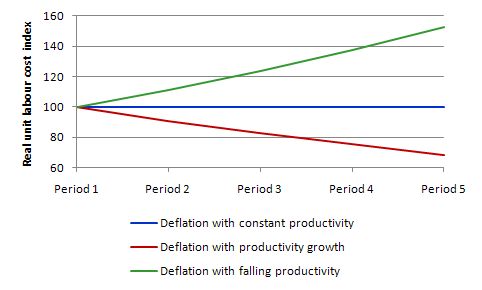

The following graph shows the four scenarios shown in the last two tables. I have dashed some scenarios to make the lines visible (given that Case A and Case C) are equivalent as are Case B and Case D. What you learn is that if wages and prices fall at the same rate and labour productivity does not rise there can be no reduction in unit or real unit labour costs.

So the internal devaluation strategy relies heavily on productivity growth occurring. The literature on organisational psychology and industrial relations is replete of examples where worker morale is an important ingredient in accomplishing productivity growth. In a climate of austerity characteristic of an internal devaluation strategy it is highly likely that productivity will not grow and may even fall over time. Then the internal devaluation strategy is useless.

This graph compares the two scenarios in the first Table with the more realistic one that labour productivity actually falls as the government ravages the economy in pursuit of its internal devaluation. As you can see real unit labour costs rise as labour productivity falls and the economy’s competitiveness (given the exchange rate is fixed) falls.

Of-course, this “supply-side” scenario does not take into account the overwhelming reality that for an economy to realise this level of output over an extended period aggregate demand would have to be supportive. The internal devaluation strategy relies heavily on the external sector providing the demand impetus.

Given that Greece trade, for example, is mostly exposed to developments in the EMU itself, it seems far fetched to assume that the trade impact arising from any successful internal devaluation will be sufficient to overcome the devastating domestic contraction in demand that will almost certainly occur. This is why commentators are calling for a domestic expansion in Germany to boost aggregate demand throughout the EMU, given the dominance of the German economy in the overall European trade.

That is clearly unlikely to happen given Germany has been engaged in a lengthy process of internal devaluation itself and the Government is resistant to any stimulus packages that might improve things within Germany and beyond via the trade impacts.

Further, the recent evidence suggests that tourism, a prime export for Greece, is suffering as a result of the civil disturbances.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

- EMU posturing provides no durable solution

- Protect your workers for the sake of the nation

- The bullies and the bullied

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

This Post Has 0 Comments