In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Australia – the inflation spike was transitory but central bankers hiked rates with only partial information

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest CPI data yesterday (June 26, 2025) – Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator – for May 2025, which showed that the annual underlying inflation rate, which excludes volatile items continues to fall – from 2.4 per cent to 2.1 per cent. The trimmed mean rate (which the RBA monitors as part of the monetary policy deliberations) fell from 2.8 per cent to 2.4 per cent. All the measures that the ABS publish (including or excluding volatile items) are now well within the ABS’s inflation targetting range which is currently 2 to 3 per cent. What is now clear is that this inflationary episode was a transitory phenomenon and did not justify the heavy-handed way the central banks responded to it. On June 8, 2021, the UK Guardian published an Op Ed I wrote about inflation – Price rises should be short-lived – so let’s not resurrect inflation as a bogeyman. In that article, and in several other forums since – written, TV, radio, presentations at events – I articulated the narrative that the inflationary pressures were transitory and would abate without the need for interest rate increases or cut backs in net government spending. In the subsequent months, I received a lot of flack from fellow economists and those out in the Twitter-verse etc who sent me quotes from the likes of Larry Summers and other prominent main stream economists who claimed that interest rates would have to rise and government net spending cut to push up unemployment towards some conception they had of the NAIRU, where inflation would stabilise. I was also told that the emergence of the inflationary pressures signalled the death knell for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – the critics apparently had some idea that the pressures were caused by excessive government spending and slack monetary settings which demonstrated in their mind that this was proof that MMT policies were dangerous. The evidence is that this episode was nothing like the 1970s inflation.

Here are some recent blog posts that relate to my analysis of the inflationary episode:

1. ECB research shows that interest rate hikes push up rents and damage low-income families (January 20, 2025).

2. So-called ‘Team Transitory’ declared victors (January 8, 2024).

3. Banks gouging super profits, yield curve inversion – nothing good is out there (October 19, 2022).

4. The inflationary episode is being driven by profit gouging and interest rate hikes won’t help much (March 27, 2023).

5. Electricity network companies profit gouging because government regulatory oversight has failed (November 22, 2023).

6. We have an experiment under way as the Bank of Japan holds its cool (March 31, 2022).

7. Two diametrically-opposed approaches to dealing with inflation – stupidity versus the Japanese way (October 6, 2022).

8. Central banks are resisting the inflation panic hype from the financial markets – and we are better off as a result (December 13, 2021).

9. The current inflation still looks to be a transitory phenomenon (March 28, 2022).

There were many more.

I think the evidence indicates that my judgement at the onset of this episode was sound, even though it was not a very widely held view by economists or policy makers.

That should tell you something.

The RBA (in line with other central banks other than the Bank of Japan) went rogue at the onset of this inflation and its public statements bore little relationship with reality.

They relentlessly pushed the line that they had to keep hiking interest rates even though the inflation peak was short-lived because they feared a wages breakout.

Various RBA officials claimed the government had to push the unemployment up to at least 4.5 per cent (when it was around 3.5 per cent) because the inflation was an excess demand-driven event and workers had to lose income to resolve the excess.

They ignored the reality that once the inflation began as a result of pandemic-caused supply constraints, exacerbated by Mr Putin’s invasion and OPEC’s temporary greed, various institutionally-driven price adjustments (such as indexation arrangements), and abuse of anti-competitive, corporate power became the problem.

There was also evidence that the RBA has caused some of the persistence in the inflation rate through the impact of the interest rate hikes on business costs and rental accommodation.

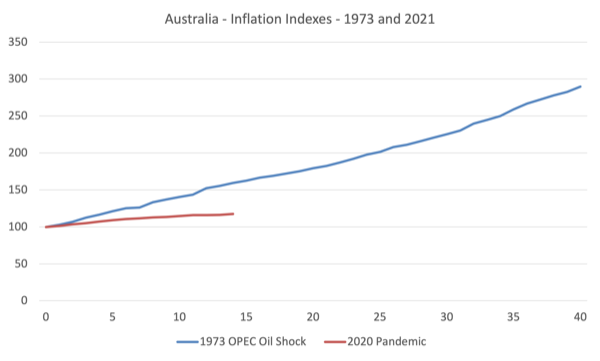

Consider the following graph, which compares the inflationary spiral that followed the October 1973 oil price hike and the recent pandemic-induced spiral.

The two series are indexed at 100 at:

1. December-quarter 1973 then out 40 quarters.

2. September-quarter 2021 then out to March-quarter 2025 (latest observation).

These quarters mark the start of each inflationary spiral.

Quite some difference!

Latest data

The latest monthly ABS CPI data shows for May 2025 that the annual price movements are:

- The All groups CPI measure rose 2.1 per cent over the 12 months (down from 2.4 in April).

- Food and non-alcoholic beverages rose 2.9 per cent (down from 3.1 per cent).

- Alcohol and tobacco rose 5.9 per cent (from 5.7 per cent)

- Clothing and footwear 1.3 per cent (from 0.8 per cent).

- Housing 2 per cent (from 2.2). Rents – 4.5 per cent (from 5 per cent).

- Furnishings and household equipment 0.9 per cent (from 1 per cent).

- Health 4.4 per cent (steady).

- Transport -2.5 per cent (-3.2 per cent).

- Communications 1 per cent (0.7 per cent).

- Recreation and culture 1.4 per cent (3.6 per cent).

- Education 5.7 per cent (steady)

- Insurance and financial services 3.1 per cent (4 per cent).

The ABS Media Release (June 25, 2025) – Monthly CPI indicator rises 2.1% in the year to May 2025 – noted that:

The monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) indicator rose 2.1 per cent in the 12 months to May 2025 …

The 2.1 per cent annual CPI inflation in May was down from 2.4 per cent in April and the lowest since October 2024 …

Annual trimmed mean inflation was 2.4 per cent in May 2025, down from 2.8 per cent in April. This is the lowest annual trimmed mean inflation rate since November 2021 …

So a few observations:

1. The underlying inflation rate is consistently falling and looks like it will go below the RBA’s lower bound for its inflation targetting range – as it was for some years before the pandemic.

2. This makes a mockery of the whole inflation targetting exercise – the RBA consistently failed to meet its target (from below) but refused to lower interest rates.

4. The electricity component is still significantly lower after the introduction of the federal and state government rebates offsetting the profit-gouging in the energy sector. This demonstrates how expansionary fiscal policy can be an effective tool in combatting inflation.

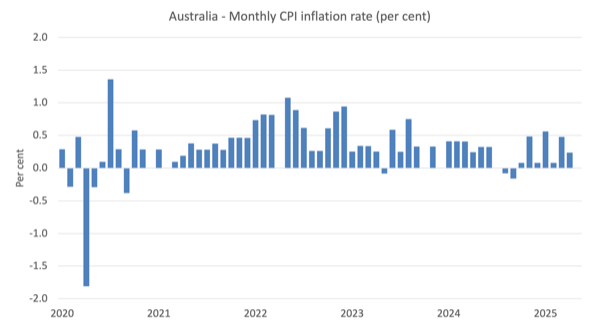

The next graph shows the monthly rate of inflation which fluctuates in line with special events or adjustments (such as, seasonal natural disasters, annual indexing arrangements etc).

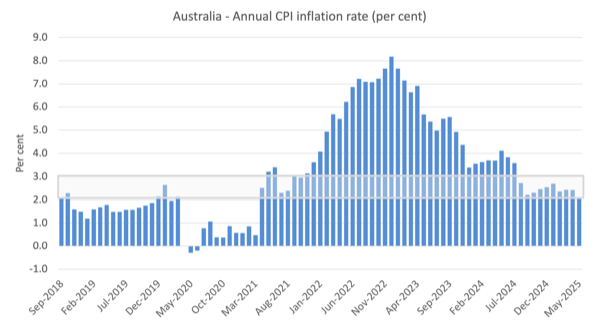

The next graph shows the annual movement with the shaded area showing the RBA targetting range.

The overall inflation rate was consistently within the targetting range since the middle of 2024.

Inflation peaked in December 2022 as the supply factors pertaining to the pandemic, Ukraine and OPEC started to abate.

The RBA kept hiking through 2023 claiming that there was a danger that wages growth would ‘breakout’ despite the fact that the data was showing no such thing with growth at record or near record lows.

It is also useful to note that prior to the inflationary episode, the RBA largely failed to keep the annual inflation rate within their target zone, which tells us about the effectiveness of the monetary policy tool in relation to its stated objective.

Household and firm heterogeneity and the implications for monetary policy

While the interest rate hikes were largely ineffective in killing aggregate spending, which was their purpose, given the RBA adopted the mainstream view that the inflation was due to excessive spending during the pandemic, they did have significant distributional effects.

Monetary policy is called a ‘blunt’ instrument because it is considered to be somewhat indiscriminate in its impacts.

That is only partially true though.

Unlike fiscal policy, monetary policy is an instrument that cannot be targetted to specific demographic or income cohorts, or regions or sectors.

In that sense, it is blunt.

But the problem is that interest rate changes do discriminate against those who are indebted and benefit those who are creditors or who hold financial wealth.

In the recent period, those holding financial wealth were given massive income boosts from the RBA interest rate hikes.

And the ‘payees’ for those gifts have been the low-income mortgage holders who are not only being squeezed by the interest rate rises directly, but are also in the front-line of the job losses that the RBA was trying to force on the economy.

These rate hikes created one of the largest redistributions of income from poor to rich in Australia’s history.

The only reason the interest rate hikes didn’t kill overall spending outright was because the beneficiaries kept spending up big on the back of the income boosts they received and inflationary impacts abated quickly enough before the losers adjusted their spending down.

There has been some damage to employment and output growth but not as significant as occurred in the late 1980s into the 1990s when the RBA engineered a massive recession.

The question of household and firm heterogeneity and its implications for the effectiveness and consequences of monetary policy changes was the topic of a major conference organised by the Bank for International Settlements on March 17-18, 2025.

On June 12, 2025, the BIS produced a volume of papers that came out of those meetings – How can central banks take account of differences across households and firms for monetary policy? – which make for interesting reading.

The BIS Background Paper carrying the same name as the conference – How can central banks take account of differences across households and firms for monetary policy? – provides an interesting overview of the issues.

It notes that central bankers have increasingly focused on the “cross-sectional differences across households and firms for the conduct of monetary policy”, which, among other reasons, is because:

… the transmission of monetary policy depends on such cross-sectional differences …

That is, how effective monetary policy is in manipulating aggregate demand shifts.

The BIS surveyed “central banks in 22 emerging market economies” to develop a knowledge base.

Factors considered are:

1. “central banks reported that the most relevant characteristics for monetary transmission include the level and type of debt, the level and source of income, and the level and liquidity of assets.”

2. “The share of so-called hand-to-mouth households (those that hold little liquid wealth and largely consume their current income) matters in particular.”

3. “In the case of firms, the most relevant characteristics are sector, size, currency exposure, the level and composition of debt, and export orientation. Monetary policy has a stronger impact on small, domestically oriented firms that tend to rely on domestic funding as compared to export-oriented or foreign-owned firms with access to diversified funding sources. In the case of both households and firms, informality further weakens transmission.”

What was significant is that:

While monetary policy can have distributional effects, central banks consider these effects to be less important than aggregate effects. When setting monetary policy, central banks focus on aggregate outcomes. Monetary policy is a blunt tool that is not well suited for influencing distributions in the population. Fiscal instruments are more easily targeted and thus more appropriate for this purpose. Moreover, vulnerable segments of society are best served when monetary policy focuses on the price stability mandate.

The problem though is that monetary policy has very large distributional effects when wealth inequality is high, as it is in most nations.

And those distributional impacts are key to determining the ‘aggregate outcomes’ because propensities to consume are starkly different across high and low income earners and high and low wealth holders.

Not only do the distributional changes impact on the aggregate but they also influence the timing of the impacts.

As I explained in many blog posts during the inflationary period, the initial impact of the interest rate rises is to gift income to the wealthy who have lower propensities to consume (that is, they will save a higher proportion of each extra dollar received than a low-income earner).

The absolute boost to nominal spending though initially is positive because low-income earners are already spending 100 per cent of their income and the high income recipients can splurge the boost.

We saw as the interest rates rose, demand for luxury cars and travel in Australia rose.

Eventually, the impact on spending reverses and the high income recipients return to more normal spending patterns while those hit with the interest rate rises start to cut discretionary spending to stay solvent with their nominal mortgage commitments, which rise as the interest rate rises flow through to all debt instruments.

Mainstream macroeconomics has always downplayed the importance of income distribution in shaping the aggregate outcomes.

The BIS research also shows that central banks, while aware of these distributional impacts do not have the modelling capacity at present to incorporate them into their decision making.

Conclusion

In other words, central banks are making monetary policy decisions that have serious implications for equity and which also seriously influence the effectiveness of their decisions without actually including in their decision-making framework essential factors.

That has been one of my major criticisms of the way central banking is conducted in this neoliberal era.

Ballistic missiles stopped me in my tracks

I didn’t make it to Europe this week as I had planned.

When I arrived at the airport on Tuesday in the early evening, I was met with the news that the flight I was booked on had been cancelled because the planes could not get into and out of Doha Airport as a result of the Iranian missile attack on the US military base.

The airline (QATAR), which regularly wins awards for service, had not even been bothered notifying those with bookings that the flights were cancelled even though they knew at 9:00 am on that day that the planes would not be arriving in time.

Stacks of people were arriving at the check-in to find the same news.

Total waste of time.

Anyway, I was able to rearrange commitments to next week (I am sorry for all the inconvenience to people at the other end) and will hope that things work out then.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The distributional effects of monetary policy choices make it impossible for the rba to set any interest rate and not have political impact. Literally transferring wealth from debtors to creditors or vice versa – that is political, creating winners and losers. The interest rate should be set by government policy, just like the tax rate or government benefit payment. Just as we don’t allow centrelink to decide the jobseeker payment amount, the rba should not be deciding interest rates.

The RBA feared a wages breakout and yet were perfectly comfortable with people losing their homes or jobs.

If the RBA was retail product they’d be rendered not fit for purpose and removed from the market.