I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

Debt is not debt

Some economists who are pushing the so-called de-leveraging story to explain the current downturn consider that the only sustainable basis for economic recovery requires that overall debt levels in the economy decline dramatically. They rightly argue that this requires a significant reduction in private debt. But they also argue that the public debt increases associated with the net public spending (the stimulus packages) – they erroneously use the term “to fund” the net spending – is self-defeating. In other words, they claim we are just substituting public debt for private debt and creating a new form of vulnerability (public insolvency – higher inflation etc) as we eliminate the private leverage. Apart from the failure of this story to link the private debt explosion with the pursuit of budget surpluses in the past, the major error that this camp makes is of the “oranges and apples” variety. That is, debt is not debt!

Yesterday, I noted that the Federal Opposition have revived their debt truck, which turns out to be a ute anyway. Given the storm about UteGate in recent weeks I would have thought the conservatives would have steered clear of utility vehicles for a while. But they are seeing political opportunities in whipping up the debt hysteria in the lead up to the next election.

As a digression, I also note that within hours of the conservatives wheeling out their “debt ute”, the Government had its own mobile advertising board claiming it had the lowest debt in advanced countries. Sort of like the “mine is bigger than yours” competitions that young boys experiment with as they approach puberty. I guess that analogy sums up what I consider to be the level of “maturity” that defines the macroeconomic debate in Australia (and around the world). Puerile at best.

Both sides of politics – those wheeling the debt truck … er ute out and the others who launched their own low debt truck/billboard in response – are only concerned with inflaming or deflaming (is that a word?) the irrational and uninformed public debate about debt. They are both prepared to trade on deliberate lies and exploit public ignorance (even their own) to further their political ambitions.

At these points in history we could have actually had a sophisticated debate which would not have focused at all on public debt but instead would have discussed the composition and size of the fiscal response necessary to stop unemployment from rising. We could also be having a serious climate change debate and a lot of other debates that are going to be essential in shaping the future of the nation.

Instead, we get debt and deficit hysteria from both sides of politics – each perpetuating equally unsustainable and erroneous macroeconomic positions.

The Opposition is trying to run the line that the debt build up will be borne by “every man, every woman and every child in Australia” and will result in higher interest rates and taxes. We have examined these questions in detail before – see my blog Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? for a reminder.

The conservatives also told ABC News yesterday that:

… the country’s debt levels would be “dramatically” lower under a Coalition government. “Not only would we have borrowed and spent less money, we would have spent money more wisely, we would have managed the economy more prudently”

The clear implication of the conservative position is that they would have had significantly lower output levels and higher labour underutilisation levels than we currently are experiencing.

If I was the Government, I would have had a larger deficit and dramatically lower public debt levels and much higher employment growth than either of them. I would have told the population that issuing public debt $-for-$ is a voluntary arrangement that the government pursues to satisfy various neo-liberal constituencies which have dominated public policy and caused unemployment to remain persistently high for decades.

I would have told the population that the question of public debt issuance in the face of rising deficits is a matter for monetary policy not fiscal policy. It is an operational matter tied up with the desire by the Government (via the central bank) to maintain a particular monetary policy stance expressed as a target interest rate.

I would have noted that if the central bank desires a positive interest rate target and it doesn’t want to pay that target rate on the overnight reserves that it holds for the commercial banks, then it has to issue debt to drain the excess reserves. Otherwise, interbank competition will wrest control of the overnight rate from the central bank. Simple as that. The two alternatives are to pay the target rate on overnight reserves or let the target rate go to zero (as the Bank of Japan did for 15 odd years).

I would have told the population (in my nightly economics bulletins on national TV and Radio! Fun times eh!), that whatever monetary policy choice the Government makes to deal with the operating factors arising from the reserve add coming from the deficit spending, the spending that I was making to underwrite employment and prosperity would still go ahead regardless. I would explain that none of these monetary operations (issuing debt, paying a support rate on reserves) has anything to do with “financing” the government spending. Children in the street would soon be noting that a sovereign government like Australia is not revenue-constrained and … they would be happier as a consequence. At least those children who were formerly growing up in jobless households.

The population would soon realise that any inference that the debt issuance will in some way restrict public spending in the future is erroneous. No child would feel that they were the bunnies who were going to bear the burden of the public debt buildup.

They would know, just like their parents came to know that if net public spending is insufficient, which it clearly is at present, then we are imposing burdens on the future generations in the form of lower income growth, less public goods, less skill development, and the rest of the advantages that come with continuous full employment.

These are real burdens. All the financial hoopla is irrelevant to judging these burdens that we are leaving for our children to bear.

It is clear that neither side of politics understands this.

This segment appeared on today’s lunchtime ABC Radio Program The World Today. The presenter Peter Cave started the segment in this way:

PETER CAVE: It’s an old idea but one worth reviving, according to the Liberal Party.

The debt truck is to make a comeback. Used more than a decade ago to highlight burgeoning foreign debt under the Keating government, the idea is being reprised, with a debt truck to travel the country advertising the Rudd Government’s economic stimulus crisis debt.

The Government has dismissed it as a “dishonest fear campaign”.

The journalist writing the story then interviewed the Temporary-Opposition Leader who said that:

MALCOLM TURNBULL: The biggest economic challenge facing Australia now is this growing level of debt that Kevin Rudd is running up … The reality is Labor is borrowing tens of billions of dollars, running into hundreds of billions of dollars of debt and having very little to show for it.

The biggest economic challenge is to stop the labour underutilisation spiral. It is to get people working again up to the hours of work they desire. It is to provide sustainable (real) growth opportunities. The level of public debt is not a economic issue.

The Government doesn’t get it either. Their spokesperson, Assistant Treasurer, Senator Nick Sherry said to the ABC:

… the facts are that government debt has been brought about predominantly by the global recession; the world financial crisis has stripped $210-billion from government revenues. That is because of the global recession.

So they are stuck in the Gold Standard days too with the implication that the debt is funding spending and if tax revenue goes you have to borrow. None of those propositions is sustainable in a fiat monetary system.

The Government spokesperson then said:

… Australia … is the best performing economy with lower debt and lower deficits than any other major advanced economy.

So the inference is that lower deficits are good even if you have 13 per cent of your willing labour resources underutilised at present! How can that be explained? What economic theory provides that conclusion. The fact is that when you have underutilised labour resources you know one other fact: government deficits are too low!

That is, the net spending by government is insufficient to fill the spending gap left by the saving desires of the private sector.

You also know you are squandering income and wealth generation opportunities that are lost forever! Some legacy to leave our children.

What if we had lower deficits than other countries and full employment? Well then we would conclude that the saving intentions of the non-government sector consistent with full employment were lower in Australia than in these other nations. That is about all you would say. Whether it was good or bad or whatever would depend on whether you thought the lower saving (more private spending as a % of GDP) was good or bad or whatever.

The economy would look different to one that had higher deficits and full employment that is clear. If you liked more public goods and less private usage of resources then you say the latter configuration was better and vice-versa.

What I would say is that both situations are eminently better than an economy that tries to minimise the budget deficit by allowing labour underutilisation to rise above the full employment level (2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment).

Debt is not debt!

So while private debt may or may not be a problem and does raise the question of solvency of the debtors public debt is never an issue in this regard. It is clearly desirable that private debt levels be reduced at this time to reduce the precarious nature of the private balance sheets. But in saying that there are no parallels that can be drawn about public debt. It is simply a totally different construction.

An economic growth strategy based on running budget surpluses (withdrawing net spending from aggregate demand) and then relying on increased private sector indebtedness (negative saving) to keep demand growing is unsustainable. We need to learn that from this current episode.

We need to learn that the budget surpluses are causally related to the private debt binge. If the private sector didn’t increasingly load itself with debt then the government sector would not be able to run surpluses for very long. The output levels (income generation system) would react to the fiscal drag and contract and the resulting cyclical downturn would, via the automatic stabilisers, push the budget into deficit up to the point that the net public spending matched the desired private saving desires. You cannot escape this.

Further, the private debt build-up cannot sustain itself if there is nothing real created. I read an interview with Paul Samuelson (94 year-old macroeconomist) in the Atlantic Monthly recently. Samuelson, for the non-economist readers, wrote the classic Keynesian textbook in the 1960s and beyond that was used all around the world. It covers the macroeconomics of the gold standard era reasonably although I didn’t like some of the political implications that he posits.

Anyway, he was asked about the current crisis and he said (in part):

What’s increased is the realization that you’ve got a free field to reach out for what you’d like to do. Everybody would still like to retire with a satisfactory nest egg in real terms. And the tragedy of this unnecessary eight-year interlude is that much of what has been accumulated is gone and gone forever. And no amount of pumping is going to bring back into reality what were ill-advised over-extensions of bridges to nowhere and housing developments for which there was no effective demand.

I will write a blog about this interview in due course. But the point is that when the financial leveraging outstrips the real economy (what is sustainable in terms of effective demand) you get problems of realisation and solvency.

I was writing about this in the mid-1990s and getting attacked by conservatives at conferences including by government officials of the day. They kept saying that there was no problem with the debt build-up. The following section comes from a paper that came out in 1995 (it is the earliest published material I can find) on the topic:

In addition, as we have argued in the last section, the corporate borrowing boom which followed financial deregulation (with 16 new foreign banks taking up the invitation to compete locally), led to an asset boom which was largely responsible for the threefold rise in the ratio of external debt to GDP.

A direct consequence of the wasteful spending practices was the loading of debt onto previously sound corporate entities (like Elders-IXL). The boom-bust cycle in asset prices was the precursor to recession. While financial deregulation was intended to generate increased competition and more services and lower prices to consumers, several negative consequences actually occurred. The high external debt ratio led to the increase in real interest rates, which choked off private investment in productive capital.

The failure of the lending boom and the massive redistribution towards the profit share to be channelled into gains in real productive capacity was a serious reflection of the Government’s diminishing grasp on the economy. It also showed the corporate sector in a poor light. The latter had argued trenchantly that the major problem was the rigidities in the labour market. However, the rapid rise in external debt would not have been a problem if it had have supported the development of productive capacity, especially in export industries. The problem was that it was largely squandered on asset transfers and unproductive real estate accumulation.

At the time, the private trends were exacerbated, and driven to some extent, by the obsession of the Hawke Government with fiscal surpluses.

My core message over many years has been that if you run surpluses, then growth can only proceed with private debt unless you have a Norwegian situation where the net exports are very strong (which cannot be a universal model). I have also consistently said that the net spending of government has to fill the saving desires of the non-government sector. These are core billy blog messages and resonate through my academic work for years now.

And as I have explained before, public debt never becomes an issue of solvency. The level of risk does not remain the same in the economy when a $ of private debt is replaced by a $ of public debt. To think otherwise is to misunderstand the role of public debt as an interest-maintenance operation within monetary policy.

External debt

The “debt ute” nonsense also recalls how convenient politicians filter the truth. You can see why the Coalition is only focusing on $300 billion which is an estimate of the buildup in public debt over the coming year. They have no credibility given they oversaw the largest expansion of private debt in this country’s history.

In 2007, Economics correspondent for The Age, Ken Davidson wrote that Foreign debt a cause for concern. He said:

ONE of the paradoxes of the Howard Government has been its obsession with reducing government debt (the debt that as taxpayers we owe to ourselves as superannuants) and its benign neglect of foreign debt (the debt that we owe to foreigners).

The reason is the policy implications of dealing with the two forms of debt. Creating a sense of crisis about Australia’s domestic debt after the 1996 election suited the Government’s political agenda. Portraying that as a crisis provided the rationale for the sell-off of most the Commonwealth’s assets (apart from Parliament House and the War Memorial) in order to pay off net government debt of just over $90 billion.

Over the same period, foreign debt has been allowed to blow out from $193 billion to about $540 billion now.

So here is a brief sojourn into external debt. You might also like to explore the resources at this ABS page – Using Foreign Investment and Foreign Debt Statistics. They provide guidance as to how not to fall into traps involving misinterpretation.

External debt data is published by the ABS in its Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, Australia (cat. no.5302.0). You can get this publication from HERE. It is quarterly data tied in with the National Accounts releases. The latest issue is March 2009.

External debt equals the borrowing of Australian residents from foreign residents. Net external debt is the gross debt minus the loans that Australian residents make to non-residents. It is often argued that external debt is only part of our external liabilities – the other part reflecting the equity claims that foreigners have as a result of purchasing shares or real estate in Australia. The sum of the two components tells us whether a country is a “net supplier of funds (debt and equity) to the rest of the world, or a net user of funds from abroad” (Source).

While that is true, we tend to concentrate on the net external debt position of a country because this component of our external liabilities involves a “contractual obligation to pay interest and principal and failure to pay then results in default and possible bankruptcy for the borrower concerned. In contrast, equity holders share in the earnings of the enterprise, with dividend payments dependent upon the enterprise having the capacity to pay” (Source).

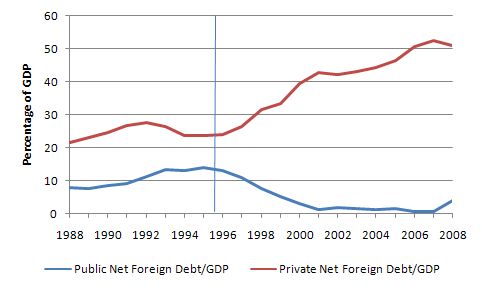

The following sequence of graphs shows the evolution of foreign debt since 1988. The first graph depicts net foreign debt as a percentage of GDP (to scale it) for the public and private sectors overall. The private sector blast off began as the Coalition took office (denoted approximately by the blue line). The mirror image is no coincidence. The fiscal squeeze created the conditions whereby households and firms had only one way left to continue to enjoy spending growth – debt. Enter the financial engineers and the rest is in the red line. The obsession with running budget surpluses (blue line) drove these dynamics. The de-leveraging camp usually ignores that causality to the detriment of their overall analysis.

Net foreign debt – public and private, 1988-2008, % of GDP

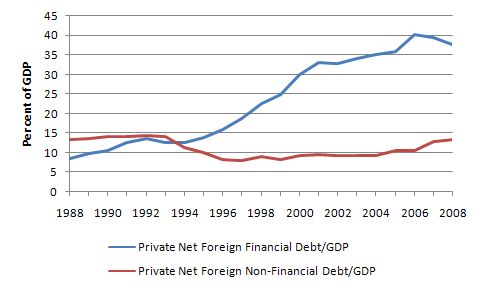

The next graph shows the composition of the private external debt between financial and non-financial enterprises. It is clear that the dramatic build-up in private external debt has been of a financial nature rather than real producing enterprises seeking investments to build productive capacity. If the debt had have been productively employed the rise in debt would have provided higher potential growth paths and probably pushed us closer to full employment.

The Federal Government was asleep at the wheel during this period totally obsessed with public debt and refusing to acknowledge that what was happening to private debt was ultimately going to come unstuck and create the situation we are now in.

Net foreign debt – private financial and non-financial enterprises, 1988-2008, % of GDP

But be careful in drawing conclusions …

Many economists do not fully understand how to interpret the balance of payments in a fiat monetary system. For example, most will associate the rise in the current account deficit (exports less than imports plus net invisibles) with an outflow of capital. They then argue that the only way we can counter this is if Australian financial institutions borrow from abroad. The result is that our net foreign debt rises in the way depicted in the graphs. They then assume that this is a problem because it means we are living beyond our means, although they rarely note that even at the top of the recent “boom” around 9 per cent of available labour resources were either unemployed or underemployed. The latter fact doesn’t tell me we are living beyond our means.

It it true that the higher the level of Australia’s foreign debt, the more our economy becomes linked to changing conditions in international credit markets. But the way this situation is usually constructed is dubious.

First, exports are a cost – we have to give something real to foreigners that we could use ourselves – opportunity cost after all!

Second, imports are a benefit – they represent foreigners giving us something real that they could use themselves but which we benefit from having. The opportunity cost is all theirs!

So, on balance, if we can persuade them to send more ships filled with things than we have to send them in return (net export deficit) then that is a net benefit to us. I am abstracting from all the arguments (valid mostly!) that says we cannot measure welfare in a material way. I know all the arguments that support that position and largely agree with them. But we are talking here using the narrow realm that professional economists confine themselves within! It is very narrow I can assure you.

So how can we have a situation where foreigners are giving up more real things than they get from us (in a macroeconommic sense)? The answer lies in the fact that our current account deficit “finances” their desire to accumulate net financial claims denominated in $AUDs. Think about that carefully. The standard conception is exactly the opposite – that the foreigners finance our profligate spending patterns.

In fact, our trade deficit allows them to accumulate these financial assets (claims on us). We gain in real terms – more ships full coming in than leave! – and they can in terms of their desired financial portfolio. So in general that seems like a good outcome for all.

The problem is that if they change their desire to accumulate financial assets in our currency then they will become unwilling to allow the “real terms of trade” (ships going and coming with real things) to remain in our favour. Then we have to adjust our export and import behaviour accordingly. If this transition is sudden then some disruptions can occur. In general, these adjustments are not sudden.

So if you understand this then you will be able to appreciate the following juxtaposition:

Neo-liberal myth: Australian consumers have to borrow $billions from foreigners to keep consuming

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) reality: Australian consumers are funding $billions in foreign savings (accumulation of $AUD-denominated financial assets by foreigners).

Here is a transactional account of how this works which starts off with me buying a French car.

- Bill buys a nice little French car.

- If I pay cash, then my bank account is debited and the French car dealer’s account is credited – this has the impact of increasing foreign savings of AUD-denominated financial assets. Total deposits in the Australian banking system, so far, are unchanged.

- If I take out a loan to buy the car, then my bank’s balance sheet now records the loan as an asset and creates a deposit (the loan) on the liability side. When I hand over the cheque to the car dealer (representing the French firm – ignore intervening transactions) the French car company has a new asset (bank deposit) and my loan boosts overall bank deposits (loans create deposits). Foreign savings in AUDs rise by the amount of the loan.

- So the trade deficit (1 car in this case) results from the French car firm’s desire to net save AUD-denominated financial assets and sell goods and services to Australia in order to get those assets – it is the only way they can accumulate financial assets in a foreign currency.

What if the French car company then decided to buy Australian Government debt instead of holding the AUD-denominated bank deposits?

Some more accounting transactions would occur.

- The French company would put in an order for the bonds which would transfer the bank deposit into the hands of the central bank (RBA) who is selling the bond (ignore the specifics of which particular account in the Government is relevant) and in return hand over a bit of paper called a bond to the French car maker’s lawyers or representative.

- The Federal Government’s foreign debt rises by that amount.

- But this merely means that the Australian Government promises, on maturity of the bond, to credit the French car firm’s bank account (add reserves to the commercial bank the car firm deals with) with the face value of the bond plus interest and debit some account at the central bank (or whatever specific accounting structure deals with bond sales and purchases).

If you understand all of that then you will clearly understand that this merely amounts to substituting a non-interest bearing reserve balance for an interest-bearing Government bond. That transaction can never present any problems of solvency for a sovereign government.

Conclusion

Somewhat discursively this blog aimed to disabuse the reader of logic that is being paraded out via the debt truck nonsense. But the more substantial point is that if you want to argue about de-leveraging then you have to understand the intrinsic relationship between the government and non-government sector and the way the currency works to define that relationship.

1. If you concentrate only on the non-government sector you will make mistakes in inference about private debt dynamics.

2. If you assume the government sector is like the non-government then you will completely misunderstand the dynamics of public debt.

For a proponent of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), private debt is not remotely like public debt. Private debt is required to “finance” private spending in excess of income, asset sales and saving. It has to be paid back by consuming less in the future.

Public debt doesn’t finance anything and doesn’t constrain the capacity of the sovereign government to spend in the future.

Tomorrow …

June Labour Force data comes out 11:30. I will surely have something to say.

Thanks Bill, always great to read your analysis. Warren Buffett has stated that the most important question to ask about economics is “And then what?” Obviously, this can be done ad infinitum.

Thus, while it is obvious that a govt with a fiat currency faces no constraint on spending, what are the considerations for the foreign net saver of that public debt? Like all savers, they are making assumptions about the strength of those savings for deferred purchasing power. To that end, they will be concerned about the level of the currency and the real purchasing power in that currency.

It seems that this can be unstable itself, as there must be a point at which the exporting country would prefer to make goods for domestic consumption. I imagine that a great deal of your writing is to articulate concepts that out-of-paradigm analysis have not considered. For those of us completely in paradigm, I’m hoping that you will walk through some of the “and then what” situations that can happen throughout the world economy that might upend the current relationships.

In particular, I wonder how long the tradeoff can exist between exporting nations wishing to keep their real wages low enough to run a trade surplus, versus the desire of current account deficit countries like the U.S. wanting to correct their severe unemployment and underemployment situation.

Does this mean that in a global economy that this must somehow eventually correct to where the marginal labor input for goods and services are relatively equal across countries? And yet we are so far from such an equilibrium now. The world has had less than a century on a fiat currency system, and has had even less time with less developed countries producing competitive manufactured goods. How might this all look in another 50 or 100 years?

Thanks again for all your insightful writing!

Roger,

I consider Warren Buffet to be an ‘outlier’ and am not a big fan of his. However I really liked your comment.

Dear Roger and Ramanan

I’m thinking about this.

best wishes

bill

Roger I liked your comment very much.

Thanks for thinking about it Bill

As an aside, Another article that does not take in to account the current monetary regime we are in, but it invokes history randomly and talks about how Keynes was not in favor of “deficit funded” public works and how the deficits should “pay” for themselves. It looks like world will need a lot of convincing to move away from the gold standard regime.

http://www.american.com/archive/2009/february-2009/taking-the-name-of-lord-keynes-in-vain

An article that got me thinking about more short-term adjustments to the current situation had the brief mention of getting to a zero current account deficit in the U.S. I’d guess that readers of this blog are also reading Wray, etc., but here’s an interesting link:

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/2009/07/coherently-confronting-us-macro.html

It took me about eight years and a worldwide financial crisis to get my head fully around this paradigm, so I no longer underestimate how much help I need to apply these ideas.

Bill, thanks for considering the question!

Cheers,

Roger

[quote]

So while private debt may or may not be a problem ….

An economic growth strategy based on running budget surpluses (withdrawing net spending from aggregate demand) and then relying on increased private sector indebtedness (negative saving) to keep demand growing is unsustainable. We need to learn that from this current episode.

[/quote]

Hi Bill

given we know the economic strategy has been to conjure a situation where we have a negative savings rate and private sector debt binge, do you think you could strike the ‘may not’ part of the first sentence. In reference to private debt ofcourse. I think the whole gfc is founded on the private sector being overly indebted, and it’s clear there is an attempt by this sector to deleverage. We’ve also seen US households savings rate increase quite substantially from a zero savings rate during the bubble.

Tricky, the “may not” part becomes relevant when the current account is in surplus. In such a case, either the public sector can be in a surplus or the private sector can be net dis-saving. I believe he mentions Norway as an example. China sounds like another.

So we do borrow from overseas but just not to fund spending ?