The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The Eurozone Member States are not equivalent to currency-issuing governments in fiscal flexibility

I don’t have much time today for writing as I am travelling a lot on my way back from my short working trip to Europe. While I was away I had some excellent conversations with some senior European Commission economists who provided me with the latest Commission thinking on fiscal policy within the Eurozone and the attitude the Commission is taking to the macroeconomic surveillance and enforcement measures. It is a pity that some Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) colleagues didn’t have the same access. If they had they would not keep repeating the myth that for all intents and purposes the 20 Member States are no different to a currency issuing nation. Such a claim lacks an understanding of the institutional realities in Europe and unfortunately serves to give false hope to progressive forces who think that they can reform the dysfunctional architecture and the inbuilt neoliberalism to advance progressive ends. There is nearly zero possibility that such reform will be forthcoming and I despair that so much progressive energy is expended on such a lost cause.

The following claim was rehearsed by two MMT economists in an article they had published in the Review of Political Economy (published February 2024):

… while there was a problem with the original set-up of the Euro system, this has been resolved in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the more recent COVID pandemic. The Euro area’s institutions allow some flexibility, allowing national governments to act as unconstrained currency issuers in times of crisis.

In conversations last week with some progressive non EC researchers and academics, I kept hearing the same narrative – ‘the European institutions work’, ‘the fiscal rules are flexible’, etc.

And that came from progressives voices rather than the technocrats in the European Commission, who reliably informed me that they were closing down the flexibility and reinforcing the discipline.

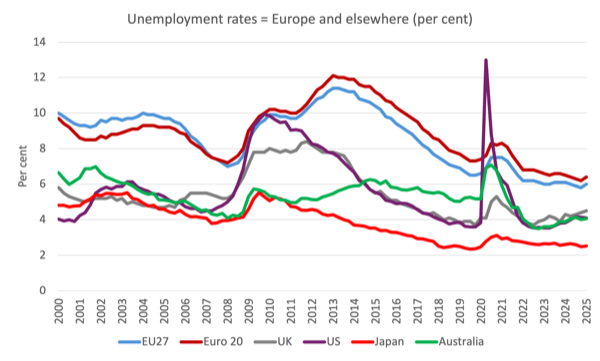

Just to set the scene here is a graph showing the relative unemployment rates for the EU27 countries, Euro20 countries, the UK, US, Japan, and Australia from the first-quarter 2000 to the first-quarter 2025.

The relative performance of the European labour markets is clearly inferior – and there is a reason for that.

The Eurozone Member States, of course, dominate the overall EU27 outcome.

The performance of the individual Member States is also generally poor.

In May 2025 the unemployment rates for 20 Member States of the Eurozone were:

Euro area 6.3 per cent

EU 5.9 per cent

Belgium 6.5 per cent

Croatia 6.1 per cent

Germany 3.7 per cent

Estonia 7.8 per cent

Ireland 4.0 per cent

Greece 7.9 per cent

Spain 10.8 per cent

France 7.1 per cent

Italy 6.5 per cent

Cyprus 3.6 per cent

Latvia 6.9 per cent

Lithuania 6.5 per cent

Luxembourg 6.7 per cent

Malta 2.7 per cent

Netherlands 3.8 per cent

Austria 5.3 per cent

Portugal 6.3 per cent

Slovenia 3.9 per cent

Slovakia 5.3 per cent

Finland 9.0 per cent

These unemployment rates are mostly elevated (by some margin) compared to most currency-issuing countries.

There is a reason for that.

Given time is short today, here is a brief summary of why the claims that the Eurozone Member States now enjoy fiscal flexibility such that they are indistinguishable from currency-issuing countries are unfounded.

First, the 20 Eurozone Member States use a foreign currency – the euro – as a result of surrendering their own capacity when they joined the Economic and Monetary Union.

The currency is issued by the European Central Bank, which is separate from any one Member State (see below).

That means that in order to spend the euro, a Member State government has to first raise taxes.

It also means, more significantly, that if a Member State wants to run a fiscal deficit, then they have to issue debt and rely on the bond investors providing the desired euros at yields that are set by the interests of the investors rather than any notion of population well-being.

Crucially, that debt comes with credit risk and the bond investors know that.

The risk is that the Member State may not be able to generate enough tax revenue to repay the outstanding debt when it matures.

There is no credit risk attached to the debt of Australia, Japan, the US, the UK etc because these governments can always through the monetary machinery of government meet any liabilities that are denominated in their own currency.

Spain, Italy and the rest of the 20 Member States do not enjoy that status.

Which means that the bond markets can ultimately make things difficult for a Eurozone state as we saw during the GFC.

Those who make the claims outlined in the Introduction claim that the ECB has shown its willingness to provide the currency necessary and control bond yields to preclude any insolvency arising.

It is obvious that during the pandemic the fiscal rules defined in the – Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – were set aside in March 2020 through the activation of the so-called ‘general escape clause’.

There are in fact two clauses:

1. The unusual events clause,

2. The general escape clause.

The European Parliament briefing (March 27, 2020) that was issued when the Commission invoked the escape clause notes that:

In essence, the clauses allow deviation from parts of the Stability and Growth Pact’s preventive or corrective arms, either because an unusual event outside the control of one or more Member States has a major impact on the financial position of the general government, or because the euro area or the Union as a whole faces a severe economic downturn. As the current crisis is outside governments’ control, with a major impact on public finances, the European Commission noted that it could apply the unusual events clause. However, it also noted that the magnitude of the fiscal effort necessary to protect European citizens and businesses from the effects of the pandemic, and to support the economy in the aftermath, requires the use of more far-reaching flexibility under the Pact. For this reason, the Commission has proposed to activate the general escape clause.

Relaxation of the fiscal rules allowed EU member states to increase spending and incur larger deficits to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic, without immediately facing penalties under the SGP.

Accordingly, for a short period the Member States could run higher fiscal deficits with the knowledge that the bond markets would not drive yields through roof.

Bond investors knew that the ECB would be buying virtually all the debt that was being issued by the individual Member States once it hit the secondary bond market which took all risk of the primary issue away and returned the market makers a tidy little, almost instant capital gain.

Interestingly, in my conversations last week, Commission economists told me they were surprised at how tentative the governments were in taking advantage of this temporary freedom.

Their scrutiny revealed that the policy makers in the Member States understood full well that the special SGP relaxation was temporary and that they anticipated that if they ran their deficits too far beyond the 3 per cent SGP threshold that the subsequent pain that would follow once the Commission resumed the enforcement of the – Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) – would be difficult to deal with.

Has this ‘freedom’ persisted?

Obviously not.

On March 8, 2023, the Commission released a memo – Fiscal policy guidance for 2024: Promoting debt sustainability and sustainable and inclusive growth – which noted that:

… fiscal policies in 2024 should ensure medium-term debt sustainability and promote sustainable and inclusive growth in all Member States …

The general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact, which provides for a temporary deviation from the budgetary requirements that normally apply in the event of a severe economic downturn, will be deactivated at the end of 2023. Moving out of the period during which the general escape clause was in force will see a resumption of quantified and differentiated country-specific recommendations on fiscal policy.

So – Protocol (No 12) – of the Treaty on European Union was back.

The operation of the EDP under – Article 126 – of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union is clear enough.

On July 26, 2024, the European Council, following the EDP rules launched the deficit-based EDP procedure against seven nations (deficits then in brackets):

Italy (-7.4%)

Hungary (-6.7%)

Romania (-6.6%)

France (-5.5%)

Poland (-5.1%)

Malta (-4.9%)

Slovakia (-4.9%)

Belgium (-4.4%)

See Council Press Release for more details – Stability and growth pact: Council launches excessive deficit procedures against seven member states (press release, 26 July 2024)Provision of deficit and debt data for 2024 – first notification – that informs the EDP.

We learned that:

Twelve Member States had deficits equal to or higher than 3% of GDP … Twelve Member States had government debt ratios higher than 60% of GDP …

So there will be more Member States added to those already tied up by the Commission in the EDP and varying austerity timelines will be imposed on them, which will prolong the elevated unemployment levels but also preclude sensible climate policy pursuits.

Further, there is a massive infrastructure deficit (crisis) in Europe as a result of years of austerity which the individual Member States haven’t a hope of addressing given the fiscal straitjacket they operate within is once again being enforced; that makes them vulnerable to domination by bond markets.

Moreover, the Member States are now being bullied by the European Commission (and Donald Trump indirectly) to ramp up military spending and the proposed – Security Action For Europe (SAFE) – under the ReArm Europe Plan will lumber them with more debt and even less fiscal latitude.

Second, no individual Member State in the Eurozone has legislative power to control the central bank – the ECB.

This is a very significant deficiency and we saw just how significant it was when in return for effectively funding the fiscal deficits of the Member States during the successive crises the ECB imposed crippling austerity conditions on the Member States.

The alternative would have been bankruptcy with no legislative recourse other than exit.

Of course, during the GFC, the European Commission feared that if one of the Member States was forced into insolvency because it could not repay outstanding debt upon maturity and/or could not afford the yields demanded by the bond markets for ongoing support as the fiscal deficits started increasing, the whole rotten system would collapse.

That is why they introduced the bond-buying programs.

But it was a political act rather than a progressive show of flexibility.

And we saw exactly what the ECB’s mentality was when the democratic trend in Greece in 2015 was indicating defiance of EC austerity stipulates.

The ECB used the threat of pushing the Greek banking system into insolvency, which led to the democratic will of the people being set aside and the so-called Socialist government turning neoliberal lackey and buckling to the oppression.

No such bullying occurs in nations that have legislative control of their central banks.

Further, the ‘once-size-fits-all’ interest rates spanning 27 economies that are vastly different in the timing and magnitude of their economic cycles means that monetary policy readily provokes economic instability.

We saw that clearly in the period before the GFC, when the ECB lowered rates because Germany and France were in recession (2004).

The lower rates, under other policy settings were inappropriate for the Southern states which were not in recession.

And the deliberate throttling of domestic demand in Germany meant that the growing trade surpluses were invested in property speculations in some of those Southern states, which came unstuck in the GFC.

Third, no individual Member State is able to control the euro exchange rate.

However, the nations with stronger trade fundamentals – meaning with surplus trade accounts – tend to dominate the dynamics of the euro foreign exchange rate and the weaker trading nations then have to accept that parity even if it would be totally at odds with the rate that would prevail if they had their own currencies and individual exchange rates.

This has been a longstanding problem in Europe since the beginning of attempts to integrate significantly different economic structures and cultures, first via the various failed attempts to fix exchange rates within the European community and then, more recently with the common currency experiment.

There is no suitable common exchange rate for the 20 Member States in the Eurozone and those with weaker trade fundamentals continually suffer competitiveness disadvantages that currency-issuing nations with their own flexible exchange rate avoid.

Fourth, those who make the claims in the Introduction then introduce another non sequitur to justify their unjustifiable assertions.

They say, for example, ‘look at the UK, they have crippling fiscal rules too’.

Or, ‘neoliberalism is everywhere’.

It is true that many nations outside Europe have succumbed to the neoliberal ideology and introduce voluntary fiscal rules as a political tool to convince voters that austerity is in their long-term best interests.

But unlike the European situation, these trends reflect the political fashion and can be varied if the fashion changes through a change of government.

In the case of Europe, the Treaties that define the legal framework that the EU operates within have embedded the neoliberalism.

That is, the ideology is embedded with the legal structure of the community that each Member State is beholden too.

That is an entirely different situation.

Article 48 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) defines the process of treaty change.

The process is excessively rigid and no Member State can act alone to alter the rules.

And on matters of substance (which the economic rules surely are) there has to be a consensus of 27 Member States for any part of the Treaty pertaining to those matters to be changed.

The issues where the so-called ‘unanimity rule’ applies and where any Member State has a ‘right of veto’ include fiscal policy, foreign policy, and admitting new countries to the EU.

The short answer is that it would be nigh on impossible to reform the neoliberal economic ideology that is embedded in the legal framework of the EU and which governs the conduct of economic policy.

Currency-issuing countries like Australia might adopt neoliberalism but if it goes too far the government is dumped as we saw in May 2022.

Voters can dump their governments in Europe too but there can be no escape from the neoliberal ideology as long as they remain members of the EU.

Conclusion

I could (and have) written more on this topic.

The problem I see is that real resistance to the capricious and destructive neoliberalism of the EU is compromised by progressives who oppose that destruction but think that better days can be had through Treaty reform.

Even worse are those who mislead by claiming that the Treaties themselves are ‘flexible’ enough to render the neoliberalism optional, which, if true, would see Greece having the same opportunities as say Australia to improve the well-being of its citizens.

It isn’t true.

Can you imagine the Socialist Greek government holding a referendum as it did in 2015 which overwhelmingly voted against austerity then telling the Greek people they were dumb and that the government was going to ignore their wishes, if Greece had its own currency and central bank and the legislative clout choose their own economic course?

I can’t.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The main issue is whether the Excessive Deficit Procedure has any teeth.

Now it certainly does against any Eurozone member who operates a ‘virtual central bank’, ie the physical Eurosystem equipment is situated in another member state – which was the problem the Greeks ran up against. They couldn’t float a ‘Greek Euro’ because the Germans could turn the Bank of Greece’s computer access off.

So the analysis is whether the enforcement of the deficit procedure has become like the enforcement of the debt ceiling in the US – fundamentally performative once the chips are down because propping up the Euro is more important than strictly following the rules. Particularly if you have a well informed government who can adopt their own bonds as the instrument required to settle taxes, and who puts in place the physical equipment necessary to decouple from the Eurosystem should the need arise.

Ultimately there is no law without enforcement. As the US is finding out, court orders are worthless if the coercive mechanism of enforcement is controlled by the person you are judging. How would that play out if, say, the Italians decided they had had enough and were going to implement full employment in Italy?

The analysis should run through exactly what the bureaucrats can actually do at a legal level if a Eurozone country simply thumbed their noses at the Commission.

The common currency means that we all have to wait for the colapse of the whole EMU (the EU?), to start thinking about the future of the EMU countries – victims of their own elites (eager to access the German Mark casino).

Leaving the EMU/EU now would be less painfull than waiting for it to crumble, but no one would accept now a return to an old and undervalued national currency.

The Brits were lucky, as they never joined the EMU joke and, therefore, it was easy for them to leave (nevertheless, they have many other parasites to deal with, as Brexit was not enough).

There is an alternative way: making the EMU a real monetary union, but just look at the “geniuses” that are leading the way.

The “washing machine” genius is now saying that europeans “share the values” of the talmud.

I wonder if there are there any values in the EU, because the talmud has none.

Taking a complete idiot and making it the leader is not new, and has been tried many times.

The only outcome of idotic ruling has been misery and death.

Am I talking about the commission president? Nooooo!

Can you please correct the 20 euro area countries? Czechia is not there. But the way, just checked open job position in ECB and there are only 7 available positions, including the internship. Scary stuff what ECB is doing with EU with all that austerity. My view is they are making EU equally poor in order not let people to migrate around the countries inside EU. Thanks for your writing, even though I totally disagree with your job guarantee concept, I am on the same page with you on ECB framework. I am just wondering how many years before EUR collapse and EU countries will back to their initial local currencies. I bet 10-20 years. If the war starts, I bet it would be quicker.

“Further, the ‘once-size-fits-all’ interest rates spanning 27 economies that are vastly different in the timing and magnitude of their economic cycles means that monetary policy readily provokes economic stability.”

Maybe stability for some but suboptimal outcomes for others? Or should that read ‘instability’?

“The lower rates, under other policy settings were inappropriate for the Southern states which were not in recession” ….

Mitchell are you buckling to monetary policy has a role to play not only driving the economy but also maintaining price stability?

Regards,

Adrian Teri

Dear Jerry Brown (at 2025/07/08 at 1:58 am)

Fixed. Thanks for the scrutiny.

best wishes

bill

Dear Adrian Teri (at 2025/07/08 at 2/l54 am).

Thanks for your enquiry.

I am not ‘buckling’ to anything. I have never said that interest rates and interest rate relativities across nations do not influence some economic and financial behaviour.

Clearly capital flows respond to interest rate shifts.

I repeatedly write about the perverse distributional impacts that interest rate changes have and the timing lags involved.

I just do not think that interest rate manipulation should be the primary source of macroeconomic counter-stabilisation policy. Such policy positions are ineffective at achieving those sorts of goals.

Finally, nothing I wrote in this blog post indicated any implied or otherwise relationship in my mind between monetary policy and price stability.

best wishes

bill

To echo @anon, Czechia is not in the eurozone; it uses the Koruna – which is maybe why it has the second lowest unemployment rate in the list! ; )

To echo @anon and @ Mr Shigimetsu.

The Czech koruna is indeed the official currency of Czechia, so it shouldn’t, strictly speaking, be included in the list of eurozone countries. It is still there at the time of writing.

I’d just make the point that if a country, such as Denmark, tightly pegs its currency to the the euro and always follows the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact (so-called) and Fiscal Compact it may as well be in the euro.

Having an independent currency then doesn’t mean that much.

Denmark would benefit its citizens by having a higher valued currency. But it chooses to keep the krone lower than free market value to maintain a near permanent export surplus. This allows it to avoid falling foul of EU rules. Unfortunately not all countries can do that. Someone has to run the deficits.

Mitchell I understand your position on counter-stabilisation however are you indicating completely zero or near zero short term rates are not adequate to attract flows to capital accounts? Only position for trade deficit(value of imports > exports) countries is to have their capital and/or financial accounts in surplus otherwise payments will not balance(barring minor discrepancies of currency exchange) – balance of payments.

On price stability yes it doesn’t feature on this post however what’s your position. Does monetary policy having an effect of correcting/stabilizing anything here?

Regards,

Adrian Teri

@ Adrian,

I’ve been mulling over the same question myself. My take below FWIW!

If the currency is allowed to freely float there can never be a balance of payments problem. So, in an economy with a freely floating currency, if we start off with a deficit in the current account there will be an equal surplus in the capital account. If that surplus falls it follows that the deficit will also fall too.

This will almost certainly have to involve a change in the forex value of the currency. So, one way to prop up the capital account and also the exchange rate is to tighten monetary policy with higher interest rates.

Letting the exchange rate fall will have an effect on perceived inflation, with higher prices, but whether this is a true measure of inflation is another question. But this has to be the thinking of the monetarists. Higher interest rates will encourage more saving in the currency but more saving also means more debt. The monetarists don’t usually explain it this way though!

My very, very short summary of Bill on Monetary Policy would be that monetary policy has some effects but these effects are often unintended or even contrary to the policy goals of full employment and price stability. That it is, in general, too broad a tool to use effectively even in the context of a single nation let alone within a monetary union of 20 or more nations. Therefore, it should not be the primary policy to use in order to stabilize much of anything. And that therefore fiscal policy is the better tool to use for those purposes and that currency sovereignty allows for much more effective fiscal policy space.

So Adrian and Peter, I would suggest that Bill might agree that higher interest rates could in some cases result in an increased demand to save in a currency which might have an effect on exchange rates but that, in itself, should not really be the goal of economic policy which is full employment and price stability within a context of overall environmental sustainability. Keeping in mind that the economy is something that is supposed to serve humanity rather than the other way around.

But keep in mind that is just my personal summary of Bill’s millions of words on the subject as I understand them.

Peter Martin many thanks for the reply.

I refute this argument of propping a currency via increasing short term rates which translates to desires of more savings. Assets issued don’t curb credit creation. If there is empirical evidence please share. This is not akin to the gold standard whereby Treasury was competing with desires to convert fixed/commodity currency. If private sector decided to get more loans gov’t either has to lower it’s spending or offer/cough up more in rates which will eventually translate to more money in future via interest income channel.

I’ve also observed 1st hand failures of this. Yes it’s a developing country with many interventions in currency markets even though authorities don’t admit it. And yes there are parts of the budget termed “development”/investment in foreign currencies. However rate hikes of ~600 Bps weren’t enough and also there wasn’t significant rise of these outlays in foreign currency but a drop. Savior was Treasury going to the crooked London markets for rollovers at higher rates & wooing jackals called Bretton Woods.

On surplus & deficit positions which causes the other. Trade or capital flows the initiator?

Regards,

Adrian Teri

Many thanks Jerry Brown for the reply.

Yes economics should serve prosperity & well-being of a people.

However I don’t see any role for monetary policy in curren[t,cy] times. Reading & listening to Mitchell he clearly puts out these assets are corporate welfare which they use to price off their riskier bets. This gives us a significant fact.

Payments/disbursements of interest to these entities and others mandated by law to hold these gov’t securities come from a gov’t spending. These investments/vehicles are just barriers that exacerbate distributional issues. If an amount was apportioned equally to a cohort of people who’ve served the commonwealth I bet this issue would be resolved in a generations time if not shorter. If you desire to play in the casino or think your animal spirits or acumen are in peak form you can go ahead however there will be no foam for a soft landing.

Regards,

Adrian Teri

@ Adrian,

I’m not totally sure what you are getting at. But I do agree that fiscal policy rather than monetary policy should have the primary role. I’m not convinced that monetary policy should have no role at all though. Fixing interest rates at 0% is fine if inflation is low and under control but that may not always be the case.

It can be difficult to know what are causes and what are the effects in the economy. Everything is interactive. So does a government deficit cause the non government sectors to be in surplus? Or is it their desire to save (ie be in surplus) that causes the government to be in deficit?

The EU’s predecessors have had some common currency regimes, especially after the late 60s when Bretton Woods started to crumble. 1971 USA/Nixon declares USD inconvertible. But in 1968, the Second Gold Exchange Standard de facto ceases to exist when the USA no longer unconditionally exchanges dollars for gold on request from central banks.

In 1969, the EEC announced plans for a currency union. In 1972, the so-called currency snake is established.

All of the currency regimes collapsed; it was blamed on members not behaving as they should.

To “solve” this, a system, the euro, was created. Lock the members in and throw away the key to make it practically impossible to leave.

Thanks Bill for a superb post on €land , i´, m eager to read your new edition of €zone dystopia

@Peter Martin

Starting back to front asking what drives the other – trade or capital flows.

On monetary policy my reading of Mitchell from Japan to America &recently ECB is that monetary policy driving the economy is pretty much done. It’s a very slow driver as evidenced by Japan & America(entering QE in 2010’s). Also frankly not fit for purpose for another aspect the dominant school of thought/mainstream economists neglect or downplay effects – Climate Change. Many can foresee an arena/carnival/musical chairs of shuffling around money instead of directing it to purposes. Appropriate analogy for the end product of the climate degradation is deformation. There’s no reversal of this damage.

On causes & effects of inflation sure might come out rude however it’s just lazy to state these can not be traced. There are 2 general sources:

(1) Aggregate demand outstripping real economy to produce stuff

(2) An external/supply/price shock that is not isolated to the distributional system

Give me an example(s) where Monetary Policy actions have assuaged or solved any event that can be generalized as above.

I don’t want to belabour more however is MMT’s counter-stabilization solution that of employed buffer stock aka Job Guarantee monetary or fiscal policy?

Regards,

Adrian Teri

@ Peter Martin

“So does a government deficit cause the non government sectors to be in surplus? Or is it their desire to save (ie be in surplus) that causes the government to be in deficit?”

Overwhelmingly the former it seems to me, since government is the one directing (or ought to be) the public purpose. If e.g. the private sector’s desire to save and consume is overheating the economy the government would likely shift to a surplus, as a policy decision regardless of what the private sector’s ‘desire’ is. Other than that the government would be running a deficit almost continually (for the sake of economic stability) which is ‘causing’ or meeting the general desire for a non government sector surplus.