With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

There will not be a fiscal crisis in Japan

The global financial press think they are finally on a winner (or should that be loser) when it comes to commentary about the Japanese economy. Over the last few years in the Covid-induced inflation, the Japanese inflation rate has now consolidated and it is safe to say that the era of deflation is over. Coupled with the government (and business) goal of driving faster nominal wages growth to provide some real gains to offset the long period of wage stagnation and real wage cuts, it is unlikely that Japan will return to the chronic deflation, which has defined the long period since the asset bubble collapsed in the early 1990s. It thus comes as no surprise that longer-term bond yields have risen somewhat. But apparently this spells major problems for the Japanese government. I disagree and this is why.

Over the weekend, there was an article in The Economist (June 21, 2025, pp.10-11) – Japan’s economy: This time it won’t end well (accessible via library subscription) – which summed up the hysteria that is developing about the recent shifts in the government yield curve.

The Economist notes that:

FOR YEARS Japan was a reassuring example for governments. Even as its net public debt peaked at 162% of GDP in 2020, it suffered no budget crisis. Instead it enjoyed rock-bottom interest rates, including borrowing for 30 years at 0.1%. Now, though, Japan is going from comfort to cautionary tale.

The article then talked about:

1. “Interest payments gobble up a tenth of the central government’s budget.”

2. “The central bank is paying out 0.4% of GDP in interest on the mountains of cash it created during years of monetary stimulus—costs that eventually land on taxpayers.”

3. “Investors are starting to ask if Japan might be vulnerable to a fiscal crisis after all.”

4. “households that will suffer if Japan’s public finances become riskier.”

And so on.

Other articles have talked about a “fiscal cliff” – metaphorically predicting Japan is about to fall off it and face major austerity demands.

The context for all this nonsense is multidimensional.

First, the reference to the central bank “paying out 0.4% of GDP in interest on the mountains of cash it created” relates to the fact that the Bank of Japan now pays a positive interest return on the excess reserves held in the accounts the commercial banks hold at the Bank.

I wrote about why this is a non issue in this blog post – Bank of Japan is making losses on its balance sheet – so what? (July 4, 2025).

If you want to learn about the interest rate support that the Bank of Japan pays on these Current deposit accounts then this page will help – What is the Complementary Deposit Facility?.

Essentially, the Bank of Japan pays the interest rate:

… to financial institutions’ excess reserves (current account balances and special reserve account balances at the Bank in excess of required reserves held by financial institutions subject to the reserve requirement system).

The support rate was first paid during the GFC, when the commercial banks started building up large quantities of excess reserves in the accounts they are required to keep at the central bank.

The scheme evolved from that time into a ‘tiered system’ where some proportion of the reserve balances received the support rate and the rest did not (with some proportion facing penalties) then in March 2024, the Bank decided to pay a positive interest rate on excess reserves.

As I have explained in the past, if there are excess reserves in the cash system and no support rate is paid, the commercial banks will try to rid themselves of the excess in the overnight market – basically lending to banks with a shortage of reserves.

Competition will drive the overnight rate down to zero and if the central bank’s monetary policy target rate is non-zero, then such a process will force it to lose control of its policy target.

So to avoid this possibility, the central banks started to offer a competitive return on the excess reserves held by the commercial banks at the central bank.

The overall support payments reflect the scale of the excess reserves.

The commercial banks have accumulated these excess reserves largely because the Bank of Japan was buying up JGBs in large quantities in the secondary bond markets.

To facilitate these purchases the Bank swaps the bonds for reserves in the commercial banks.

The capacity to make that transaction comes from the fact that the Bank of Japan can always just click a few computer keys to type yen-denominated amounts into the accounts of the commercial banks – ex nihilo.

To suggest that the Current deposits are funding the Bank of Japan is to render the term ‘funding’ meaningless.

In fact, the currency-issuing capacity of the Bank of Japan is what ‘funds’ the excess reserves held at the Bank by the commercial banks (and other financial institutions).

Once you understand that point, then the rest of the propositions advanced in this regard are untenable.

The support rate is currently around 0.1 per cent in line with the recent adjustment in the policy rate that the Bank of Japan announced.

Obviously, if the Bank increases its policy rate in the coming months (as part of its misguided notion of policy normalisation) then the support rate will rise too.

The payment of the support rate is totally voluntary and at the discretion of the Bank of Japan.

The Bank of Japan could simply go back to pre-GFC policy and leave the support rate at zero but that is another story.

If there was ever a hint of financial crisis then the Bank of Japan has all the policy capacity to provide remedies.

A non-issue.

Second, why are the long-term bond yields rising and what does it mean?

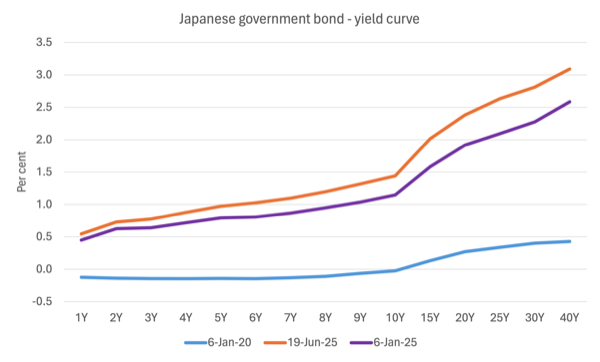

The following graph shows the evolution of the Japanese government yield curve since the onset of the pandemic.

A yield curve simply plots the yields for the different bond maturities (1-year, 2-year etc) that are on issue.

A currency-issuing government could stop issuing debt at any time it wanted and the bond markets would have to create their own benchmark, low-risk asset to replace the risk-free government assets.

Ignoring specific nuances of a particular country, governments match their deficits by issuing public debt. It is a totally voluntary act for a sovereign government.

The debt-issuance is a monetary operation and is entirely unnecessary from an intrinsic perspective.

Governments (more or less) use auction systems to issue the debt. The auction model merely supplies the required volume of government bonds at the price that emerges in the bidding process Typically the value of the bids exceeds by multiples the value of the overall amount the government is seeking.

A primary market is the institutional machinery via which the government sells the bonds. There are, typically, selected financial institutions that participate in the primary issue and ‘make’ the market.

A secondary market is where existing financial assets are traded by interested parties. So the financial assets enter the monetary system via the primary market and are then available for trading in the secondary.

Secondary market trading has no impact at all on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders.

The way the auction works is simple. The government determines when a tender will open and the type of debt instrument to be issued. They thus determine the maturity (how long the bond would exist for), the coupon rate (the interest return on the bond) and the volume (how many bonds).

The issue is then put out for tender and demand relative to the fixed supply in the market determines the final price of the bonds issued.

Imagine a $1000 bond had a coupon of 5 per cent, meaning that you would get $50 dollar per annum until the bond matured at which time you would get $1000 back.

Imagine that the market wanted a yield of 6 per cent to accommodate risk expectations. So for them the bond is unattractive and so they would put in a purchase bid lower than the $1000 to ensure they get the 6 per cent return they sought.

The general rule for fixed-income bonds is that when the prices rise, the yield falls and vice versa.

Thus, the price of a bond can change in the market place according to interest rate fluctuations.

When interest rates rise, the price of previously issued bonds fall because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering a higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increase, becoming more attractive as newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

So for new bond issues the government receives the tenders from the bond market traders which are ranked in terms of price (and implied yields desired) and a quantity requested in $ millions.

The government then issues the bonds in highest price bid order until it raises the revenue it seeks. So the first bidder with the highest price (lowest yield) gets what they want (as long as it doesn’t exhaust the whole tender, which is not likely). Then the second bidder (higher yield) and so on.

In this way, if demand for the tender is low, the final yields will be higher and vice versa.

Rising yields on government bonds do not necessarily indicate that the bond markets are sick of government debt levels.

In sovereign nations (not the EMU) it typically either means that the economy is growing strongly and investors are willing to diversify their portfolios into riskier assets.

Or it can mean that that the central bank is pushing up its policy rate and bond yields more or less follow.

The Ministry of Finance publishes – Historical Data of Auction Results – which allow us to see what was going on in the primary market with respect to demand for bonds.

The media is claiming there has been a dramatic drop in demand for Japanese government bonds lately – particularly long-dated issues.

The auction data shows a reduction in demand (hardly dramatic) and the Bid-to-Cover ratios are now around 2.5 to 2.7, which means that there are 2.5 times the bids for the debt than there is debt for sale.

Hardly a disaster!

What determines the slope of the yield curve?

There are various theories about the yield curve and its dynamics. All share some common notions – in particular that the higher is expected inflation the steeper the yield curve will be other things equal.

I outlined these theories in this blog post – Banks gouging super profits, yield curve inversion – nothing good is out there (October 19, 2022).

The basic principle linking the shape of the yield curve to the economy’s prospects is explained as follows.

The short end of the yield curve reflects the interest rate set by the central bank.

The steepness of the yield curve then depends on the yield of the longer-term bonds, which are set by the auction process.

One of the risks in holding a fixed coupon bond with a fixed redemption value is purchasing power risk.

Purchasing power risk is more threatening the longer is the maturity.

So it is one reason why longer maturity rates will be higher. The market yield is equal to the real rate of return required plus compensation for the expected rate of inflation.

If the inflation rate is expected to rise, then market rates will rise to compensate.

In this case, we would expect the yield curve to steepen, given that this effect will impact more significantly on longer maturity bonds than at the short end of the yield curve.

So the basic reason for the shifts in the graph shown above relates to the fact that positive (and relatively stable) inflation is now core in Japan and investors are building that into their expectations and desiring higher yields on long-term assets.

No cause for alarm.

Third, Japan will go to the polls for their Upper House elections next month and the Ishiba government has announced new fiscal measures to ease the cost-of-living pressures (and get votes).

The availability and price of rice has been a contentious issue over the last year or so and the Government is proposing to provide cash grants to households.

The media have dubbed this reckless expenditure.

To put this in perspective adults will receive just ¥20,000 – a pittance.

The Economist thinks that this “is a worrying sign for an indebted country which, like most of the rich world, faces immense fiscal pressure”.

Excuse my laughter.

The Economist also claims that the “Japanese people … would, in all likelihood, have to endure prolonged and destabilising inflation if public debt became unsustainable.”

Of course they don’t exactly state how:

(a) the public debt could become unsustainable given the Japanese government only issues in yen and has infinite (minus one yen) supply of it.

(b) prolonged inflation will result – how? The debt repayments are unlikely to be spent on consumer goods – given the bond holdings represent portfolio decisions about the stock of wealth held in the non-government sector.

So the cash tied up in the bond purchases was not being spent on goods and services anyway.

And even if there was a shift to higher consumption spending that would just reduce the fiscal deficit and the debt-issuance would decline.

In that scenario, one would be hard pressed to say that there productive capacity of the Japanese economy is already exhausted.

If you spend any time in Japan it is apparent that the opposite is the case – there is plenty of spare capacity and there are lots of firms just hanging on to viability with small volumes of sales that could easily scale up quickly.

Fourth, part of the decline in demand for the JGBs is due to the Bank of Japan reducing its purchases of government bonds in the secondary market as part of its ‘normalisation’ strategy.

The primary bond market makers have known for years that they can flip the JGBs they bid for in the secondary market for a profit because the Bank of Japan was buying up big.

But the Bank can easily shift policy again – tomorrow if it wanted to – and increase its demand for the JGBs in the secondary market if it felt that the price of bonds had fallen too far due to lack of private demand.

The Bank can set whatever yield it wants by the volume of its purchases.

Again, a non issue.

Conclusion

There will not be a fiscal crisis in Japan.

Mark my words.

Admin Note

From tomorrow, I will be working in Europe for a week and it might take some time to respond to comments etc. Normal service will resume next week, although I will try to write up some work I am doing for Thursday’s blog post this week. We will see how things go – I have a lot of commitments crammed in.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

They are whining about interest on reserves now. They don’t do that with the US I think, usually the focus is on interest on Treasuries, with interest on reserves by Fed ignored even though its still free money.

Regardless, “a journal that speaks for the British millionaires”.

Paper money, with no intrinsic value, is all about wealth transfers.

Transfers from the lower classes to the elites, mainly through inflation processes.

Transfers from the Global South to the parasitic colonialists in the west (through exchange rate manipulation, IMF/WB imposed austerirty, resource theft, dollar standard imposition on imports and so many other ways of stealing from the poor countries).

The game has two sides.

The one side that looses the game is the side that accepts the conditions of the other side.

Clearly, Japan is not on the beggars side.

MMT seems to me to be a correct understanding of money and how it is used in modern financial interactions underneath the obfuscations, that is, caused by the general misunderstanding of the function of money. Therefore those with a full understanding of money, such as you folks writing for New Perspectives should be able to predict financial events with much greater accuracy, as you are have done here regarding expectations of the Japanese economy.

Those of us less expert but convinced of the theoretical soundness of your understandings, then, would greatly appreciate ongoing commentary on financial events as they took place. Indeed, your insights should equip us to choose much more wisely which investments to avoid and which to commit to.

My personal example is the wisdom of holding high interest debt funds, which I am doing using the guidance of Steve Bavaria on Seeking Alpha. What is an MMT influenced view on this general area of investment?

Thank you for any response you can provide and your general discussions such as this one.

John Rose

Dear John Rose (at 2025/07/07 at 7:33 am)

Thanks for your interest in MMT.

With respect to your question, I am an academic researcher not a financial forecaster. I provide no guidance here or elsewhere in my work to support speculative strategies.

best wishes

bill