I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

Treasurer, please sack the RBA governor and the Monetary Policy Board members – they have gone rogue

Once again the Reserve Bank of Australia has gone rogue. On Tuesday (July 8, 2025), it held its cash rate target (the interest rate that expresses its monetary policy stance) constant at 3.85 per cent despite all the indicators suggesting that it would cut that target rate. The financial markets are in uproar because they bet on the cut and will have lost money on a myriad of speculative bets based on that expectation. I don’t care about that. But what I care about is that the RBA decision continues to punish low-income mortgage holders and reward high income holders of financial assets, thus continuing one of the most pernicious redistributions of income in the history of our nation. Moreover, the logic expressed by the RBA indicates they really have no idea of what the reality of the situation is and are rather living in a world of fictional economics that reality has exposed to be false. The Treasurer should sack the Governor and her underlings as well as dismissing the Monetary Policy board who have, in my view, failed. Such systematic failures should require the RBA officials to be dismissed.

In its – Statement on Monetary Policy February 2025 – the RBA noted that:

Monetary policy has been restrictive and will remain so after this reduction in the cash rate. However, the outlook remains uncertain. In removing a little of the policy restrictiveness, the Board acknowledges that progress has been made but is cautious about the outlook.

At that point, the RBA had just lowered the cash rate target by 25 basis points from 4.35 per cent to 4.10 per cent.

How did they come to the conclusion that “Monetary policy has been restrictive and will remain so”, even after they cut the rate by 1/4 of a per cent?

By comparing the cash rate target in place with their concept of a “neutral rate” – which is the rate they claim that monetary policy is neither adding to aggregate demand nor subtracting from it.

In that February Statement they write:

The cash rate remains above estimates of the neutral rate, consistent with the ongoing weakness in private demand …

The cash rate is above the RBA’s and market economists’ central estimates of neutral (Graph 1.5). However, there is a large degree of uncertainty about these estimates. There is a wide range of model estimates, and each individual estimate is subject to its own uncertainty. Accordingly, the neutral rate is difficult to identify and incoming data and refinements to models can lead to significant revisions. The RBA has recently refined how the models account for the pandemic period, following the techniques of other central banks. This has led to a shift downward in some estimates of neutral and is consistent with our assessment, based on a broader range of indicators, that financial conditions remain restrictive and the observation that private demand has been weak for some time.

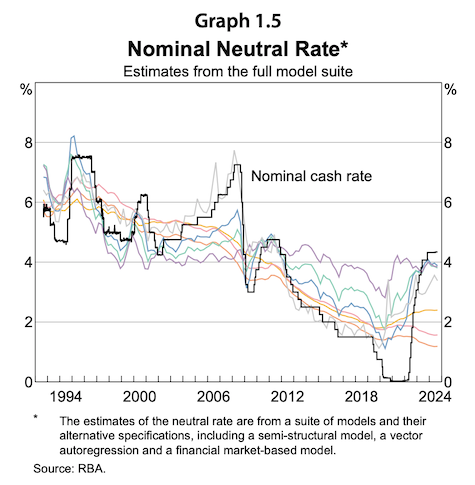

Graph 1.5 (mentioned in that quote) is reproduced as follows:

You can see how the nominal neutral rate (various coloured lines) varies according to the econometric and statistical techniques used to measure it.

It is a very precise concept in theory but a very imprecise concept in terms of trying to estimate it empirically.

It is one of those concepts in economics that pretend to impart precision to policy making but which makes it impossible to be applied in any meaningful way in terms of precise policy adjustments.

Consider the various lines which reflect the different ways of trying to estimate the concept empirically.

At the end of 2024, they were suggesting the neutral rate was anywhere between around 1 per cent and close to 4 per cent.

So how would a policy maker come to a conclusion that they were in expansionary or contractionary policy mode?

Using the model that estimated the neutral rate to be around 1 per cent, any cash rate target above that would suggest a contractionary stance.

But what happens if the true neutral rate was 4 per cent and the RBA was trying to be contractionary by setting the rate at 2 per cent (thinking the neutral rate was 1 per cent)?

Well then monetary policy would be expansionary and the policy makers would be doing exactly the opposite to what they intended with the opposite consequences (if there were any).

But we also know that the RBA’s own conclusion about the neutral rate is that they think it is around 2.9 per cent after the ‘revisions’ they noted in the above quote.

Previously, the RBA had used a neutral rate of around 3.5 per cent.

Now why does that matter?

Well with an alleged ‘neutral’ rate of 2.9 per cent, then it is clear that the RBA believes its current monetary policy stance expressed by its 3.85 per cent target rate is contractionary.

The cash rate target is above their estimate of the neutral rate.

What does that imply?

Clearly, the RBA wants to push unemployment higher by continuing to run a contractionary policy stance.

Otherwise, they would have reduced the cash rate target down substantially.

Note: I am using the RBA’s own logic here and the effectiveness of the policy tool for achieving the aims they set is another matter altogether.

We are putting ourselves in the position of the policy board and applying the logic that they hold out.

Now, why would they want to push up unemployment rate up when inflation is in decline (substantially)?

The answer, which I have written about a lot in the past, is that they think the Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment – the NAIRU – is above the current unemployment rate.

For background, please consult these earlier blog posts on this topic:

1. Mainstream logic should conclude the Australian unemployment rate is above the NAIRU not below it as the RBA claims (July 24, 2023).

2. RBA wants to destroy the livelihoods of 140,000 Australian workers – a shocking indictment of a failed state (June 22, 2023).

Let’s put ourselves in the shoes of a mainstream New Keynesian economist for a moment – the type of thinking that dominates central bank economists.

We would never want to walk in them for long because our self esteem would plummet as we realised what frauds we were.

But suspend judgement for a while because to understand what is wrong with the current domination of macroeconomic policy by interest rate adjustments one has to appreciate the underlying theory that is guiding the central bank policy shifts.

The New Keynesian NAIRU concept, which stems from work published in 1975 by Franco Modigliani and Lucas Papademos is pretty straightforward even if economists shroud it in mystery – to make themselves appear smarter than the rest.

Accordingly, NK economists define an unemployment rate, above which inflation falls and below which inflation rises.

So that unique rate (or range of rates to cater for uncertainty of measurement) is the stable inflation rate – where inflation neither falls nor rises.

This is the NAIRU.

Logically, if the unemployment rate had been stable for some period, yet inflation was continuously declining, then they would conclude that the stable unemployment rate must be ABOVE the NAIRU and vice versa.

So the RBA has a self-confessed ‘contractionary’ policy stance which means they want to suppress spending further and drive up the unemployment rate because they believe the current unemployment rate is below the NAIRU.

They have believed this since they started hiking rates (May 2022) at which time the official unemployment rate was 3.91 per cent.

As they hiked rates further through 2022 and 2023 (ending in November 2023), the unemployment rate continued to fall reaching a lower point of 3.516 in December 2022.

That month, incidentally, was the turning point in the recent inflation spiral.

From that point, inflation in Australia has fallen consistently from the December 2022 peak 8.17 per cent to its current value of 2.1 per cent (May 2025).

Has the RBA said anything specific about its estimate of the NAIRU?

In this blog post – Mainstream logic should conclude the Australian unemployment rate is above the NAIRU not below it as the RBA claims (July 24, 2023) – I documented various commentary from RBA officials on that issue.

A 5 per cent rate sort of became a benchmark for the profession only because in the initial academic paper on the topic from Modigliani and Papademos, they came to the conclusion that unemployment rates above 5 per cent are largely associated with decreasing inflation rates while unemployment rates below 5 per cent are largely associated with noticeable increases in the inflation rate.

I considered the technical issues involved about that in this blog post – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! (April 16, 2009).

In our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned – we analysed the topic in depth.

The RBA and the Australian Treasury held on to a 5 per cent NAIRU benchmark (or around that) for a long time.

In recent times, the RBA governor has told an audience in the Q&A during her presentation – Achieving Full Employment – Newcastle (June 20, 2023) – that

… the unemployment rate will have to rise … the NAIRU … 4½ probably looks, we think, maybe in the ballpark.

In the Speech-proper, she said:

The unemployment rate is expected to rise to 4½ per cent by late 2024 … While 4½ per cent is higher than the current rate, this outcome would still leave us below where it was pre-pandemic and not far off some estimates of where the NAIRU might currently be. In other words, the economy would be closer to a sustainable balance point.

When the Governor made those outrageous comments, the official unemployment rate was 3.5 per cent.

It was clear that the RBA justified its interest rate hikes with the assertion that the unemployment rate of 3.5 per cent was below the RBA’s NAIRU estimate and that they need to drive the official unemployment rate up to 4.5 per cent to achieve price stability.

More recently, the RBA has revised its NAIRU estimate down further to 4.25 per cent.

Notwithstanding that, the current unemployment rate of 4.1 per cent remains below the RBA’s revised NAIRU estimate.

So if there was any validity to the framework, we should observe inflation rising not falling.

Which tells you everything.

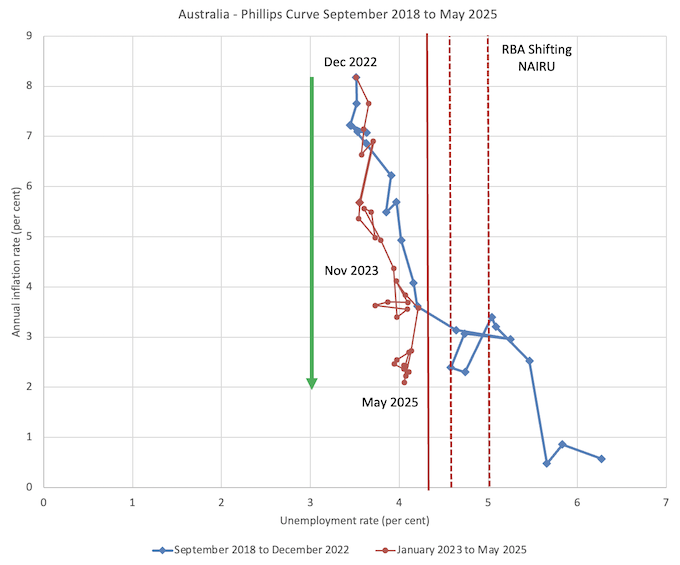

The next graph which I updated to show the latest data depicts what economists call a Phillips curve.

It shows the official unemployment rate (horizontal axis) and the annual inflation rate (vertical axis) for Australia from September 2018 to May 2025 (using Monthly CPI data).

The sample is divided into two segments:

1. September 2018 to December 2022 (blue) when the inflation rate was rising.

2. January 2023 to May 2025 (red) when the inflation rate was falling.

I have also shown the shifting RBA NAIRU estimates.

What do you observe?

1. The unemployment rate became very stable around 3.5 or 3.7 per cent from around May 2022 (which was the month the RBA started hiking).

2. The inflation rate rises during the worst of the pandemic as a result of the massive supply impediments that COVID-19 created exacerbated by the Ukraine situation and OPEC+.

3. The inflation rate peaked in December 2022, after which it declined steadily even though the unemployment rate remained very stable throughout the rise and fall period.

What do you conclude from that?

Using the RBA’s NAIRU logic, it would be difficult to conceive of the NAIRU in Australia being as high as 4.25 per cent or anything close to that.

Applying that logic would suggest the NAIRU if it existed must be below an unemployment rate of 3.5 per cent given that stable level of unemployment was associated with a declining inflation rate since December 2022 (with a short monthly sampling fluctuations).

So why is the RBA insisting on running a contractionary monetary policy and desiring higher unemployment?

In their – Statement by the Monetary Policy Board: Monetary Policy Decision (issued July 8, 2025) – they claimed that:

… various indicators suggest that labour market conditions remain tight. Measures of labour underutilisation are at relatively low rates and business surveys and liaison suggest that availability of labour is still a constraint for a range of employers. Looking through quarterly volatility, wages growth has softened from its peak but productivity growth has not picked up and growth in unit labour costs remains high.

They are thus still claiming that the inflation outlook is uncertain and that the possibility of a wages breakout is still on their minds.

So they want the unemployment rate to rise to suppress this phantom wage pressure.

I say phantom because there is zero evidence that wages growth is accelerating or was ever going to accelerate throughout this whole hiking period.

And so the RBA wants to destroy livelihoods based on archaic fictions which have no grounding in the evidential world.

Conclusion

The point is that the theory that surrounds the NAIRU concept and its application to monetary policy is relatively clear.

I disagree with it and consider it to be flawed in both theoretical and empirical terms.

But that aside, one cannot just use these concepts to suit themselves.

If one considers the NAIRU concept to be robust then it means that one would conclude the NAIRU is below the current unemployment rate.

All the evidence would support that conclusion.

The RBA, however, despite its claim to offer robust scrutiny to support its policy decisions, claims the NAIRU is still above the current unemployment rate.

But then they have to explain why the inflation rate has been steadily decreasing since December 2022 while the unemployment rate has been relatively stable at a level well below their NAIRU estimate.

You can’t have it both ways.

Sack the lot of them!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Perhaps the RBA is not abstracting away from the fact that economic growth is inherently environmentally damaging? Perhaps they realize that a world of dead coral reefs, an acidic Southern Ocean, and horrifying heat will harm the most vulnerable the most?

“We would never want to walk in [their shoes] for long because our self esteem would plummet as we realised what frauds we were.”

Great line.

It constantly amazes me how supposedly educated people rationalize their harmful policies based on completely discredited theories and ignore empirical reality.

Having endured two seasons of unprecedented drought conditions while interest rates have been hiked unnecessarily, I thoroughly endorse Bill’s sentiments regarding the Reserve Bank Governor and Board.

Reading Bill’s regular analysis of the inflation episode and the inappropriate response by the Reserve Bank has been a welcome diversion from the day to day challenges posed by lack of feed, water and income.

Even more frustrating to me than the performance of the bank’s governor and her board is the willingness of the Federal Treasurer to accept their failings without criticism. Jim Chalmers has thus clearly signalled his refusal to use the power he still has (thanks to a public outcry when he tried to relinquish that power) to ensure that the Reserve Bank serves the national interest.

Whenever there has not been a strong, principled Labor government in Australia, the Reserve Bank and its predesessor, the Commonwealth Bank have preferenced the interests of bankers and investors at the expense of ordinary people for whom life is often a struggle.

Conservative governments (including the Labor incumbent) have enabled this by appointing boards which are loyal to the financial sector rather than the country as a whole, and pretending that the unelected board members can ignore direction from to the country’s electected representatives.

It is therefore difficult not to believe that the Reserve Bank Governor’s apparent misinterpretation of the NAIRU concept is more about loyalty to the wishes of the international banking community to maintain high interest rates than simply incompetence in processing the facts before her.

Or perhaps Jim Chalmers hasn’t got a clue either!

Cs, they are like Swift’s Laputan scientists crafting schemes to construct houses from the roof downwards or to reconstitute sunlight from cucumbers. They are anti-empirical exponents of an anti-scientific priesthood.

The RBA serves the interests of the wealthy without a care in the world of how it impacts anyone else.

The ALP government won’t do anything because they know if they don’t tow the line they will be out of government before they can blink.

Sack the lot of them doesn’t go far enough.

We need a royal commission into the RBA Board and an explanation how in Australia we have gone from the Big Four commercial banks to the Big One and three much smaller ones.

Paragraph 1 final sentence: “Such systematic failures should require the RBA officials to be dismissed.”

Did you perhaps mean “systemic” failures, rather than “systematic”?

Dear Graham (at 2025/07/28 at 7:!2 am)

Thanks for your comment and query.

No, I meant systematic – as in regular and sequential mistakes of the same type. It is also a systemic failure as well.

best wishes

bill