I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

A modern monetary theory lullaby

In recent comments on my blog concern was expressed about continuous deficits. I consider these concerns reflect a misunderstanding of the role deficits play in a modern monetary system. Specifically, it still appears that the absolute size of the deficit is some indicator of good and bad and that bigger is worse than smaller. Then at some size (unspecified) the deficit becomes unsustainable. There was interesting discussion about this topic in relation to the simple model presented in the blog – Some neighbours arrive. In today’s blog I continue addressing some of these concerns so that those who are uncertain will have a clear basis on which to differentiate hysteria from reality. We might all sleep a bit better tonight as a consequence – hence the title of today’s blog!

I should note at the outset that these simple teaching models are only designed to reinforce the stock-flow relations at the sectoral level and show the inevitable relationships that follow from the national accounts when discretionary action is taken by, say, the government to cut back its deficit. They are not intended to incorporate all macroeconomic behaviour and system interactions. Then we would lose the message.

If you consider the headline from this article in yesterday’s WSJ, then it is clear that those concerned individuals would start resonating.

The headline read: Foreign Demand Of US Assets Slows In December and within a few hours I was receiving E-mails from the deficit terrorists who seem to think it is okay to regularly send me E-mails … as if they know me … without starting with “Dear Bill” or any other form of polite introduction.

They typically then immediately launch into some asinine diatribe, interspersed with comments such as – “you see, despite what you say, China is bailing out … its all about to go up in smoke” or “interest rates are about to jack up what do you say now Professor” – sometimes with some additional colourful terms – such as “socialism” or “fu##wit” appended. Such politeness always suggests to me that this crowd must have had stable upbringings with a sound primary school education!

Now let me be absolutely clear – no-one who is nice enough to comment on my blog whether pro or con in relation to the argument I present there write these E-mails. I welcome all constructive comments and contributions to the billy blog community. These E-mails I get are another matter altogether and the descriptor spam comes to mind.

As an aside, the IP addresses from the E-mailers are 99 per cent of the time from US routers which doesn’t say they are Americans but is suggestive. I sense there is real angst in the US and a lot of it is being fuelled by these so-called financial market experts who wouldn’t know what day it was.

As an another aside – in relation to “what day it is”: (humour coming up) – a few years ago a US sociology professor (or some such) was being interviewed by our national radio broadcaster the ABC about his forthcoming trip to Australia to present a paper at a conference. At some point in the interview he said “and by the way what month is it down there” (it was mid-May, so it wasn’t a dateline issue). It was funny. By the way, many of my best mates are … you guessed it … Americans.

Anyway, back to that WSJ article which reported that:

China continued to sell U.S. Treasurys in December, dropping to the second-largest foreign holder after Japan, raising concerns of a permanent shift out of the dollar. Foreigners were net buyers of long-term U.S. assets in December, though the pace slowed and a record amount of Treasury bills were dumped.

I am not sure why this would raise any concerns at all. Who buys the government paper is somewhat irrevelant. Whether anyone buys the paper should also be irrelevant to a fiat currency issuing government but that is another story given the voluntary arrangements (constraints) that the US government like most sovereign governments impose on themselves.

Anyway, China is now a “major net seller of Treasurys” and is possibly “moving forward with plans to diversify out of U.S. assets”. The WSJ says it is suggestive whereas I prefer “possibly” because they wouldn’t know anyway.

The WSJ quoted some character at the Brookings Institution (and a former IMF official) as saying:

China is trying to send a subtle economic and political message to the U.S. through the deployment of its foreign exchange reserve holdings.

It is not very subtle if that is what they are doing. Further, Chinese officials are smart enough to realise that the US government ultimately doesn’t care if China hold the paper or not. Someone else will if they don’t. If China think it now has leverage power of the US government then they are stupid or the US government is stupid or both.

But I thought the interesting point that was not mentioned in the WSJ report is that bond yields have been very stable. As my mate Marshall Auerback noted in correspondence with me today, this is a denial of the hoopla that is trotted out daily by the same characters that send me E-mails.

The folklore they are trying to etch firmly into the public debate is that when China finally sells of its US bond holdings, those yields will sky-rocket, no-one else will want the debt and it will be the end America as we know it.

You can get daily US yield curve data from the US Treasury Department. It is aslo an excellent data source which I use often.

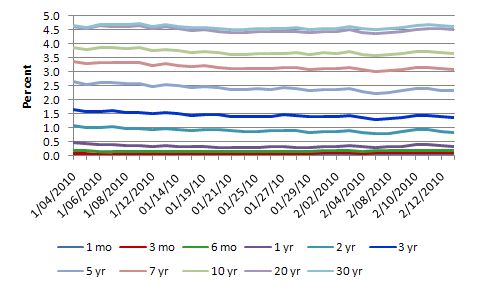

The following very colourful graph shows the US government bond yields for each maturity (months and years) since January 4 until February 16 (yesterday). So time is on the horizontal axis and yields are on the vertical axis. The various time-series are then the different bond maturities.

The conclusion you reach is that nothing much is happening at all. Yields at all maturities are stable despite the implications of the headlines. If the world was about to fall in you would not be observing such stability. If anything the yields are edging down a bit. You can see that in the next graph.

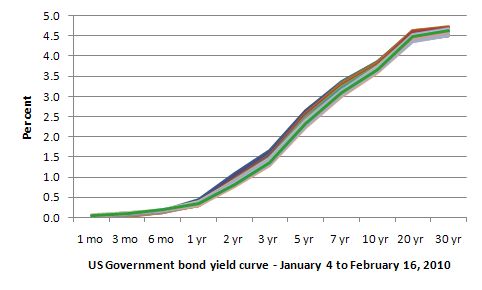

If you want to see the daily yield curve (which just plots time (maturity) on the horizontal axis against yield on the vertical axis) since January 4 to February 16 then here it is. There are actually 30 daily curves here and the story is one of great stability. The curve is upward sloping which is normal and reflects the expected inflation risk of holding bonds out to 30 years given they are nominal rather than indexed.

You can some slight movement down (the thickening) but you can conclude for all operational reasons that the 30 curves plotted are virtually identical.

So bad luck to those who are looking for bad news in the US bond markets.

If I examined yields in Japan, Australia – places that are not tied into the current Eurozone debacle then the same story would be observed.

Remember this blog – D for debt bomb; D for drivel – where a so-called expert Australian bond analyst was commenting on the Australian bond market in July last year. He introduced the topic with statements such as an “Alarming debt bomb is ticking”; “Funding for Australia’s huge deficit … threatened by a nearly saturated bond market”; “A looming crisis in the financial markets is threatening the ability of the Federal Government to finance its fiscal stimulus”.

It was asinine exemplified.

The commentator then said that:

An unprecedented amount of debt threatens to strangle the bond market and place a dire dependence on foreign investment to fund the budget deficit … with each tender now becoming a growing burden on the level of available cash for investment in the market, risks are rising. One gauge of investor interest is the bid/cover ratio. When bids exceed issuance by around three-to-one or greater, the auction is generally considered successful. Twice last month, bid/cover was below two.

You will see at the time the commentator just revealed his ideological biases and his lack of acumen. Looking back the commentary was even more laughable than it was then given we have more data.

Bond yields and bid/cover ratios have hardly budged – you can see the data from the Australian Office of Financial Management.

Some history

In a recent speech the President, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Thomas Hoenig, made the following statement:

Throughout history, there are many examples of severe fiscal strains leading to major inflation. It seems inevitable that a government turns to its central bank to bridge budget shortfalls, with the result being too-rapid money creation and eventually, not immediately, high inflation. Such outcomes require either a cooperative central bank or an infringement on its independence. While many, perhaps most, nations assert the importance and benefits of an independent central bank, the pressures of the “immediate” over the goals of the long run makes this principle all too expedient to forgo when budget pressures mount.

He then went onto to discuss Germany in 1920s but didn’t have the outright audacity to move onto Zimbabwe. Neither historical examples have any bearing on the current circumstances. Please read my blog – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on this point.

But the important historical point is that there are many more examples of governments running continuous budget deficits with some central bank support (I don’t just the term printing money or even money creation as above) for extended periods where inflation has not been an issue.

Most of the significant inflationary episodes in the last 50 years have been sourced in supply-side shocks rather than demand pull situations arising from aggregate demand outstrippling the real capacity of the economy to respond via output increases.

I will examine the Hoenig speech in more detail in another blog because it is getting some mileage out there and needs to be carefully rebutted. The rebuttal is easy – the speech was near hysteria but it will take more time than I have today.

Further while historical appreciation is very important, it is also crucial to understanding scale. It is never sensible to react to statements like “record levels of debt” or “massive budget deficits” or “unprecendented levels of spending”. If levels mattered then how would you compare the US deficits (trillions) to Australia (billions). We must be great and then if we compare them to Haiti, Australia would be awful.

You always have to judge these things in terms of scale and what the movements in the other significant and interlinked aggregates are. The purpose of the simple teaching models was to bring those interlinked aggregates into sharp relief to get people thinking about the interrelatedness of macroeconmics. I will come back to this point in the next section of the blog.

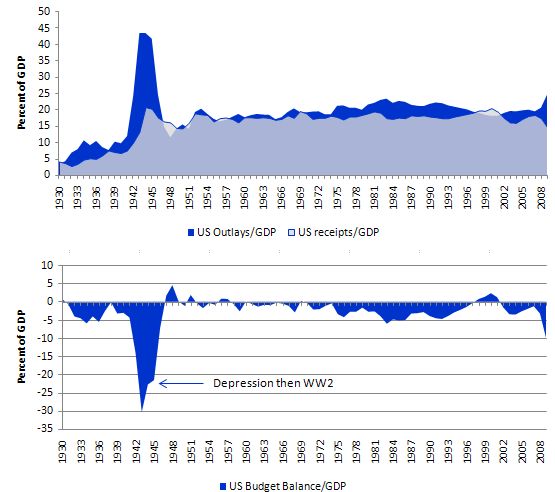

But here is some history. The following graph reminds us that today and yesterday are short spans of time. The data is from the US Office of Management and Budget historical data which is an excellent source of long time series for US public sector data.

For the 79 year period shown, the US government’s budget was in deficit of varying proportions of GDP 67 of those years (that is, 84 per cent of the time). Each time the government tried to push its budget into surplus, a major recession followed which forced the budget via the automatic stabilisers back into deficit.

These deficits have provided support for private domestic saving over most of this period. The US current account was in surplus (very small though) up until the 1970s and then has been more or less in deficit since the mid-1980s and increasingly so in the 1990s and beyond.

In times of crisis – the Great Depression and World War 2 – you can see the deficit grew relatively large and national debt followed it upwards as a percentage of GDP. Then as growth resumed and stability was re-established the deficit fell back as a percentage of GDP to the level required to support private domestic saving and maintain aggregate demand to support relatively high (but not high enough) employment levels.

Movements in interest rates and inflation rates and changes to US tax regimes bear no statistically significant relationship with the fiscal parameters over this entire period. The strongest relationship that can be established is the relationship between deficits and expenditure and hence economic growth (and employment growth).

So the question that has to be answered by those who are predicting the end at the moment is this – given the historical period experience – why are the current Deficits/GDP, which are smaller by a long way from what they were in the 1930-40s, suddenly signalling something that is unsustainable?

The first response will be the ageing society and health issues are different now. Yes they are but those issues are erroneous distractions. Please read my blog – Another intergenerational report – another waste of time – for more discussion on this point.

There are no other credible responses. The US economy will resume growth – the automatic stabilisers will go to work and eat into the budget deficit and the US will cut back stimulus spending to further reduce the deficit. Private domestic saving will stabilise as private balance sheets are restored to some semblance of sustainability following the private debt binge and the net public spending required to support that saving and maintain growth will also stabilise.

In 10 years time, all the hysterical commentary and angst will be revealed as nonsense. If you want to be comforted I suggest you go back to the 1930 and read some of the conservative literature that was published then. You will get such a sense of deja vu. Then re-examine the following graph to see that things turn out okay!

Further, in the period following the Great Depression the US and all of us ran convertible, fixed-exchange rate currency systems which made it much harder to make the adjustments to net spending etc. In our fiat monetary systems of today the financial constraints are all voluntary.

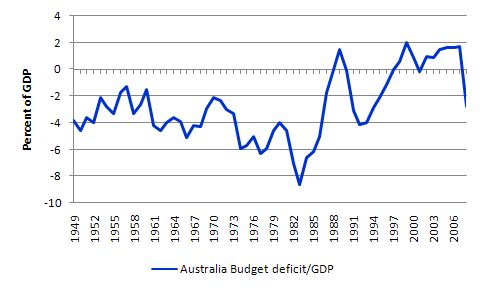

For Australian readers, the following graph shows the budget deficit as a percentage of GDP since 1949. Our data is not nearly as good as that kept and made available by the US government. Trying to match up earlier data is very difficult so I refrained in this instance.

Once again you can see that we have run continuous budget deficits over a very long period. Each time the government tried to run surpluses recessions followed. In the last period (1996-2008) the surpluses squeezed the private domestic sector so badly (given we almost always have run a current account deficit) that the levels of household indebtedness relative to income rose to dangerous levels.

As in the US case, movements in interest rates and inflation rates and changes to tax regimes bear no statistically significant relationship with the fiscal parameters over this entire period.

Similarly, the strongest relationship that can be established is the relationship between deficits and expenditure and hence economic growth (and employment growth).

So when is a deficit bad?

Essential background reading includes the following blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Then you should read these more specific blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3.

In summary, when considering the concept of fiscal sustainability the following points are important guide posts:

- Saying a government can always credit bank accounts and add to bank reserves whenever it sees fit doesn’t mean it should be spending without regard to what the spending is aimed at achieving.

- Governments must aim to advance public purpose.

- Fiscal sustainability is not defined with reference to some level of the public debt/GDP ratio or deficit/GDP ratio.

- Fiscal sustainability is directly related to the extent to which labour resources are utilised in the economy. The goal is to generate full employment.

- A sovereign (currency-issuing) government is always financially solvent.

- You cannot deduce anything about government budgets by invoking the fallacious analogy between a household and government.

- Fiscal sustainability will not include any notion of foreign “financing” limits or foreign worries about a sovereign government’s solvency.

Attention to these guideposts should alert one to when a spurious argument is being made or not. Here is some more detailed explication which establish some overriding principles of modern monetary theory (MMT) in this respect and should be used when appraising whether a particular fiscal policy strategy is sustainable or not.

Advancement of public purpose

The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose. In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

Given the non-government sector will typically desire to net save (accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue) over the course of a business cycle this means that there will be, on average, a spending gap over the course of the same cycle that can only be filled by the national government. There is no escaping that.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap. However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the budget outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs). But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The budget will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment – which I define as 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

Understanding the monetary system

Any notion of fiscal sustainability has to be related to intrinsic nature of the monetary system that the government is operating within. It makes no sense to comment on the behaviour of a government in a fiat monetary system using the logic that applies to a government in a gold standard where the currency was convertible to another commodity of intrinsic value and exchange rates were fixed.

Please read the blog – Gold standard and fixed exchange rates – myths that still prevail – for further discussion on the financial constraints that applied to governments in that sort of system.

A government operating in a fiat monetary system, may adopt, voluntary restraints that allow it to replicate the operations of a government during a gold standard. These constraints may include issuing public debt $-for-$ everytime they spend beyond taxation. They may include setting particular ceilings relating to deficit size; limiting the real growth in government spending over some finite time period; constructing policy to target a fixed or unchanging share of taxation in GDP; placing a ceiling on how much public debt can be outstanding; targetting some particular public debt to GDP ratio.

All these restraints are gold standard type concepts and applied to governments who were revenue-constrained. They have no intrinsic applicability to a sovereign government operating in a fiat monetary system. So while it doesn’t make any sense for a government to put itself in a strait-jacket which typically amounts to it failing to achieve high employment levels, the fact remains that a government can do it.

But these are voluntary restraints. In general, the imposition of these restraints reflect ideological imperatives which typically reflect a disdain for public endeavour and a desire to maintain high unemployment to reduce the capacity of workers to enjoy their fair share of national production (income).

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability does not include any recognition of the legitimacy of these voluntary restraints. These constraints have no application to a fiscally sustainable outcome. They essentially deny the responsibilities of a national government to ensure public purpose, as discussed above, is achieved.

Understanding what a sovereign government is

A national government in a fiat monetary system has specific capacities relating to the conduct of the sovereign currency. It is the only body that can issue this currency. It is a monopoly issuer, which means that the government can never be revenue-constrained in a technical sense (voluntary constraints ignored). This means exactly this – it can spend whenever it wants to and has no imperative to seeks funds to facilitate the spending.

This is in sharp contradistinction with a household (generalising to any non-government entity) which uses the currency of issue. Households have to fund every dollar they spend either by earning income, running down saving, and/or borrowing.

Clearly, a household cannot spend more than its revenue indefinitely because it would imply total asset liquidation then continuously increasing debt. A household cannot sustain permanently increasing debt. So the budget choices facing a household are limited and prevent permament deficits.

These household dynamics and constraints can never apply intrinsically to a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system.

A sovereign government does not need to save to spend – in fact, the concept of the currency issuer saving in the currency that it issues is nonsensical.

A sovereign government can sustain deficits indefinitely without destabilising itself or the economy and without establishing conditions which will ultimately undermine the aspiration to achieve public purpose.

Further, the sovereign government is the sole source of net financial assets (created by deficit spending) for the non-government sector. All transactions between agents in the non-government sector net to zero. For every asset created in the non-government sector there is a corresponding liability created $-for-$. No net wealth can be created. It is only through transactions between the government and the non-government sector create (destroy) net financial assets in the non-government sector.

This accounting reality means that if the non-government sector wants to net save in the currency of issue then the government has to be in deficit $-for-$. The accumulated wealth in the currency of issue is also the accounting record of the accumulated deficits $-for-$.

So when the government runs a surplus, the non-government sector has to be in deficit. There are distributional possibilities between the foreign and domestic components of the non-government sector but overall that sector’s outcome is the mirror image of the government balance.

To say that the government sector should be in surplus is to also aspire for the non-government sector to be in deficit. if the foreign sector is in deficit the national accounting relations mean that a government surplus will always be reflected in a private domestic deficit.

This cannot be a viable growth strategy because the private sector (which does face a financing contraint) cannot run on-going deficits. Ultimately, the fiscal drag will force the economy into recession (as private sector agents restructure their balance sheets by saving again) and the budget will move via automatic stabilisers into defict.

Further, given the non-government sector will typically net save in the currency of issue, a sovereign government has to run deficits more or less on a continuous basis. The size of those deficts will relate back to the pursuit of public purpose.

Understanding why governments tax

In a fiat monetary system the currency has no intrinsic worth. Further the government has no intrinsic financial constraint. Once we realise that government spending is not revenue-constrained then we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light. The starting point of this new understanding is that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

In this way, it is clear that the imposition of taxes creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector and allows a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector, which in turn, facilitates the government’s economic and social program.

The crucial point is that the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending. Accordingly, government spending provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economics that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment. As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal total income (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not each period). Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages).

Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account, but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal. As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

The purpose of State Money is for the government to move real resources from private to public domain. It does so by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue. To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets). From the previous paragraph it is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In our conception, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending decisions in force at any particular time.

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability does not entertain notions that the continuous deficits required to finance non-government net saving desires in the currency of issue will ultimately require high taxes. Taxes in the future might be higher or lower or unchanged. These movements have nothing to do with “funding” government spending.

To understand how taxes are used to attenuate demand please read this blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory.

Understanding why governments issue debt

The fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows.

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about ‘crowding out’.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

Accordingly, debt is issued as an interest-maintenance strategy by the central bank. It has no correspondence with any need to fund government spending. Debt might also be issued if the government wants the private sector to have less purchasing power.

Further, the idea that governments would simply get the central bank to “monetise” treasury debt (which is seen orthodox economists as the alternative “financing” method for government spending) is highly misleading. Debt monetisation is usually referred to as a process whereby the central bank buys government bonds directly from the treasury.

In other words, the federal government borrows money from the central bank rather than the public. Debt monetisation is the process usually implied when a government is said to be printing money. Debt monetisation, all else equal, is said to increase the money supply and can lead to severe inflation.

However, as long as the central bank has a mandate to maintain a target short-term interest rate, the size of its purchases and sales of government debt are not discretionary. Once the central bank sets a short-term interest rate target, its portfolio of government securities changes only because of the transactions that are required to support the target interest rate.

The central bank’s lack of control over the quantity of reserves underscores the impossibility of debt monetisation. The central bank is unable to monetise the federal debt by purchasing government securities at will because to do so would cause the short-term target rate to fall to zero or to the support rate. If the central bank purchased securities directly from the treasury and the treasury then spent the money, its expenditures would be excess reserves in the banking system. The central bank would be forced to sell an equal amount of securities to support the target interest rate.

The central bank would act only as an intermediary. The central bank would be buying securities from the treasury and selling them to the public. No monetisation would occur.

However, the central bank may agree to pay the short-term interest rate to banks who hold excess overnight reserves. This would eliminate the need by the commercial banks to access the interbank market to get rid of any excess reserves and would allow the central bank to maintain its target interest rate without issuing debt.

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability should never make any financing link between debt issuance and net government spending. There is no inevitability for debt to rise as deficits rise. Voluntary decisions by the government to make such a link have no basis in the fundamentals of the fiat monetary system.

Setting budget targets and inflation

Any financial target for budget deficits or the public debt to GDP ratio can never be a sensible for all the reasons outlined above. It is highly unlikely that a government could actually hit some previously determined target if it wasn’t consistent with the public purpose aims to create full capacity utilisation.

As long as there is deficiencies in aggregate demand (a positive spending gap) output and income adjustments will be downwards and budget balances and GDP will be in flux.

The aim of fiscal policy should always be to fulfill public purpose and the resulting public debt/GDP ratio will just reflect the accounting flows that are required to achieve this basic aspiration.

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability cannot be sensibly tied to any accounting entity such as a debt/GDP ratio.

Inflation will only be a concern when aggregate demand growth outstrips the real capacity of the economy to respond in real terms (that is, produce more output).

After that point, growth in net spending is undesirable and I would be joining the throng of those demanding a cut back in the deficits – although I would judge whether the public/private mix of final output was to my liking before I made that call. If there was a need for more public output and less private then I would be calling for tax rises.

This is not to say that inflation only arises when demand is high. Clearly supply-shocks can trigger an inflationary episode before full employment is reached but that is another story again and requires careful demand management and shifts in spending composition as well as other measures.

Foreign issues

First, exports are a cost and imports provide benefits. This is not the way that mainstream economists think but reflect the fact that if you give something away that you could use yourself (export) that is a cost and if you are get something that you do not previously have (import) that is a benefit.

The reason why a country can run a trade deficit is because the foreigners (who sell us imports) want to accumulate financial assets in $AUD relative to our desire to accumulate their currencies as financial assets.

This necessitates that they send more real goods and services to us than they expect us to send to them. For as long as that lasts this real imbalance provides us with net benefits. If the foreigners change their desires to hold financial assets in $AUD then the trade flows will reflect that and our terms of trade (real) will change accordingly. It is possible that foreigners will desire to accumulate no financial assets in $AUD which would mean we would have to export as much as we import.

When foreigners demand less $AUD, its value declines. Prices rise to some extent in the domestic economy but our exports become more competitive. This process has historically had limits in which the fluctuations vary. At worst, it will mean small price rises for imported goods.

If we think that depreciation will be one consequence of achieving full employment via net government spending then we are actually saying that we value having access to cheaper foreign travel or luxury cars more than we value having all people in work. It means that we want the unemployed to “pay” for our cheaper holidays and imported cars.

I don’t think the concept of fiscal sustainability should reflect these perverse ethical standards.

Further, foreigners do not fund the spending of a sovereign government. If the Chinese do not want to buy US Government bonds then they will not. The US government will still go on spending and the Chinese will have less $USD assets. No loss to the US.

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability does not include any notion of foreign “financing” limits or foreign worries about a sovereign government’s solvency.

Understanding what a cost is

The deficit-debt debate continually reflects a misunderstanding as to what constitutes an economic cost. The numbers that appear in budget statements are not costs! The government spends by putting numbers into accounts in the banking system.

The real cost of any program is the extra real resources that the program requires for implementation. So the real cost of a Job Guarantee is the extra consunmption that the formerly unemployed workers can entertain and the extra capital etc that is required to provide equipment for the workers to use in their productive pursuits.

In general, when there is persistent and high unemployment there is an abundance of real resources available which are currently unutilised or under-utilised. So in some sense, the opportunity cost of many government programs when the economy is weak is zero.

But in general, government programs have to be appraised by how they use real resources rather than in terms of the nominal $-values involved.

Accordingly, the concept of fiscal sustainability should be related to the utilisation rates of real resources, which takes us back to the initial point about the pursuit of public purpose.

Fiscal sustainability will never be associated with underutilised labour resources.

Conclusion

I have clearly traversed this ground before but to welcome newcomers to the discussion it is always worth repeating key concepts that emerge from MMT. In defining a working conceptualisation of fiscal sustainability I have avoided very much analysis of debt, intergenerational tax burdens and other debt-hysteria concepts.

These concepts are largely irrelevant once you understand the essential nature of a fiat monetary system and focus on the main aim of fiscal policy which is to pursue public purpose.

This discussion should support the simple teaching models that I have made available. It should provide a very clear indication of the basic concepts that should be used when assessing whether a particular fiscal position is sustainable or not.

That is enough for today!

it would be nice if you addressed specific cost increases caused by inelastic government demand. when government demands a product at any cost the price tends to be inflated and bloated which is a waste of real resources and makes goods much more expensive for private sector buyers (we’re looking at you U.S health care spending). i think you should do a blog post about the microeconomic effects of government spending and taxing because when you read someone like warren mosler you get the feeling that if we just cut a bunch of taxes all would be right with the world which i personally don’t agree with but also don’t think you do either (or for that matter warren mosler himself).

ok – maybe i can ask a simple question.

Bill, you wrote “The folklore they are trying to etch firmly into the public debate is that when China finally sells of its US bond holdings, those yields will sky-rocket, no-one else will want the debt and it will be the end America as we know it.” and then later “If the Chinese do not want to buy US Government bonds then they will not. The US government will still go on spending and the Chinese will have less $USD assets. No loss to the US.”

For some reason I’m reminded of Hank Paulson’s quote about how if you have a bazooka in your pocket, and everyone knows it, then you won’t have to use it. The difference is that everyone knows China makes defective guns, and we’re not afraid of their bazooka because we don’t think they have a working one (Sorry – lame humor attempt). I mention this because you seemed to be trying to show, way above, that because yields on government bonds didn’t jump, this means they WILL not jump. The market clearly doesn’t believe China’s bazooka threat to sell Treasuries. Are you really suggesting that IF they did sell their treasury holdings that there is another suitable buyer for them? I’m guessing that what you’re suggesting is that we don’t NEED another buyer for them – we (The US Gov’t) just print money on our sovereign printing press and pay them back, right? Am i ok so far?

So, let’s say that when the debt China is holding matures, instead of buying new debt with it (rolling their position), they say they want their money back. We print up a fresh trillion dollars (digital or otherwise) and give it to the Chinese. Now, they either 1) sell the $$$ and buy Yuan and take them back to China (unlikely?) or 2) buy real assets in our country with our currency (more likely?)

when China takes its trillion dollars and starts buying up US real estate, ports, sports teams, and businesses, doesn’t that have a real (negative) effect on me – The American Who Now Has To Pay Higher Prices Because I’m Competing With The Chinese For Assets? I could have also called myself The American Who Has Savings And Doesn’t Want To See The Purchasing Power of Them Reduced.

Dear Kid Dynamite

Implicit in your question is the assumption that China and the rest of the world in general will at some point in the near future choose to run trade deficits with the US . . . big ones, as that’s the only way they reduce their net savings in dollars. I’m curious which country or countries you think that might be?

While I wouldn’t myself necessarily assume the rest of the world will necessarily desire trade surpluses with the US forever, one also has to recognize that the reversal of this is what is required for your scenario to even be plausible. And, even in that case, many nations have shown that it is possible to have strong currencies and positive trade balances simultaneously (i.e., Japan . . . which has the world’s largest (or thereabouts) national debt ratio, to boot).

Best,

Scott

Thanks Scott – that’s a key point.

you are saying that China will continue to have dollars because we buy their goods – they have a big trade surplus with us

BUT, isn’t the net effect on ME different if they take their dollars and buy US debt at 4% yield or if they buy up real physical assets?! ie, if China holds financial assets, it doesn’t really bother me – in fact, i WANT them to (keeps rates low!) – but if they swap financial assets for real physical assets, it has a real negative effect on ME… no?

I should add that IF the rest of the world decides to run large trade deficits with the US, it is at that moment that MMT tells you a smaller government deficit is appropriate, as the improved trade balance results in greater utilization of the economy’s capacity; running deficits the same size as previously (with a trade deficit) would not be the MMT proposal, unless the domestic private sector were raising its own desired net saving in lock-step with the reversal of the trade balance. If the trade surplus is large enough, then even a budget surplus might be appropriate.

This is separate from Bill’s point above that imports are a benefit and exports are a cost, which remains true.

Best,

Scott

I’m curious about where the two percent figure for determining “full employment,” comes from. I’ve been looking through articles on the COFFEE and CFEPS websites for a discussion of how this number was determined and I can’t seem to find anything directly on point. Given the amount of thought put into the analysis I read here at billy blog and at the Economic Perspectives from Kansas City website I can’t believe the two percent figure is just a made up, arbitrary number like the NAIRU. Even the people who promote NAIRU have some justification for their figures. Could someone please point me in the right direction. Thank you.

“they either 1) sell the $$$ and buy Yuan and take them back to China (unlikely?) or 2) buy real assets in our country with our currency (more likely?)”

# 1 can’t happen. At best, PBOC could reverse its domestic FX transaction policies, and “buy back” the Yuan liabilities it created when it bought dollars from its exporters, but that would simply transfer China’s long dollar position from PBOC to the private sector. The long dollar position for the country would remain. Apart from that, PBOC can only buy Yuan from the rest of the world to the degree that the rest of the world has existing Yuan claims on China, which is very minimal. (They could sell their long dollar position to the rest of the world outside of the US (for non-dollar, non-Yuan FX), but they’re still locked into a long FX position of some sort (as a current balance sheet condition) as a country, due to their cumulative current account surplus. The future trajectory of their current account is what drives the future trajectory of their long FX position.)

If they do # 2, they are effectively swapping existing dollar financial claims on the US for direct investment in the US. US sellers of direct investment will be supplied the dollars to enable purchase of the treasuries (with associated global portfolio adjustment, no doubt). Remember that China is the one on the bid for hard assets in that scenario, so the sellers of the hard assets would get their price, and therefore would be prepared from a portfolio perspective to redeploy into financial assets. There’s no reason to believe that the bid for hard assets wouldn’t be beneficial in terms of producing a natural knock-on bid for treasuries with the proceeds from the asset sale, a bid that would be helpful in reversing any price effect of the original sale of treasuries.

I expect that my question has already been addressed somewhere on this site, but where? 🙂

“Debt monetisation is usually referred to as a process whereby the central bank buys government bonds directly from the treasury.

“In other words, the federal government borrows money from the central bank rather than the public. Debt monetisation is the process usually implied when a government is said to be printing money. Debt monetisation, all else equal, is said to increase the money supply and can lead to severe inflation.”

What would be the effect if, instead of borrowing money from the central bank, the treasury did not borrow at all? (In the U. S., that would require a change in the law, I expect.)

Many thanks. 🙂

Dear Sir,

You briefly mention the problem of cost shock driven inflation, as opposed to demand driven inflation. It would be interesting to hear your views on how best to conduct policy under such a cost shock. Especially since the inflation of the 1970s was used by the monetarists to misleadingly discredit the postwar consensus, of whose full employment policy objective was not responsibly for the real decline in the supply of oil which was the source of that inflation.

While we can see in Japan clear empirical evidence that there is no significant tradeoff that has to be made between unemployment and inflation (as it has had consistently lower unemployment and lower inflation in the postwar period than nearly all other developed economies, despite big dependence on imported commodities), it would be nice to have a full blown discussion on the issue of a cost shock, unemployment and inflation.

In my own view it seems rather counter-productive to excessively deflate an economy encountering an oil shock but also that it seems counter-productive to excessively inflation an economy encountering an oil glut. A collapse in oil prices could well cause beneficial (supply expansion driven, as opposed to 1930’s depression 1990s Japan and a large part of the world today’s demand collapse driven) deflation in oil consuming countries that would coexist with full employment.

No offense intended, but I think the statement: “…exports are a cost and imports provide benefits,” is a bit too simplistic. Exporting goods and services also has the tendency to develop productive capacity, which can absolutely be a benefit. For example, China’s export led strategy for economic growth has been hugely successful even though it has come at the cost of depriving its own citizens of consumption opportunities. IMHO, relying on foreign countries to provide real goods and services to the extent the U.S. has over the past ten to twenty years or so creates a dependency that is not healthy for a modern society. Personally, I feel finding a way to create a more even balance of trade arrangement, whether that be through transaction taxes, capital controls, import quotas, import-export certificates, or whatever, is an important part of solving the numerous problems facing the U.S. and world economy. I’d be curious to know if MMT has anything more to say about balance of payment issues. Maybe it’s just that I’ve only been reading billy blog and the Perspectives from Kansas City website for under two months, but I haven’t really found much discussion of these kinds of issues.

Min,

The monetarists out there hold increases in the money supply lead directly to inflation. They are drawing from the old quantity theory of money which holds velocity and employment constant in the standard mv = pq equation. Professor Mitchell and the other Chartalists say velocity and employment are not fixed and therefore increasing the supply of money will not necessarily lead to inflation. There is ample research supporting the view that v and q is not fixed, but really all you need to do to confirm this is look out the window. The U.S. economy has not been anywhere close to full employment for over forty years so a fixed q is clearly out. Furthermore, anyone with eyes to see should be able to tell you that in times of economic uncertainty (i.e. now) people are less willing to spend, so a fixed q is also obviously out. So, in answer your question, if the treasury didn’t borrow at all and just increased the money supply, it is likely employment would increase. However, it also depends on how that money is spent. Normally, deficit spending puts downward pressure on interest rates so it is also possible that increasing the money supply could fuel asset price bubbles. You can see some of that today in the burgeoning U.S. dollar carry trade. To counter asset price bubbles appropriate fiscal policy and regulatory intervention is also necessary. I hope that helps.

Back when Tokyo was worth more than the entire US, the Japanese tried number 2 and got burned buying Hollywood studios, etc. I doubt that the Chinese want to come in and start buying up real estate (commercial buildings anyone?) or other US assets for that matter. They have enough to do internally – unlike Japan which is pretty much built out.

For being worthless, I’m sure those Treasuries are used for collateral for other trade dealings, like trying to buy Australian mining companies.

Hello,

I wandered over from Kid Dynamite’s site and spent a while reading this post. First off let me say that your writing and knowledge of the subject seem very deep so thanks for the take.

I really cannot debate the nuances of monetary policy with you, I think its mostly a joke and a huge game of pretend (and it is well over my head!) but I noticed as all other number cruncher types, I failed to see any context commentary in your writing. There was a massive credit bubble and it collapsed, do models exist that can offer a take on “if” something should be done and not just the “how”? Maybe home prices are still too high and the “how” of supporting them, transferring the debt onto the public balance sheet, has nothing to do with whether this is a goal worth chasing.

I am trying to absorb as much of MMT as I can in a short amount of time. I understand and agree with much of what you said but I get stuck on “exports are a cost”. Putting aside the way GDP is typically calculated, sure, there is probably a theoretical basis for such a statement but in reality when trading partners are not equal or are behaving in a way that doesn’t benefit both trading partners then how can exports be considered a cost?

Unfettered globalization has hurt U.S. manufacturing base and has acted as a deflationary means on wages of U.S. workers. – that to seems to be two very big costs of exports.

Your thoughts.

ugg, I should make use of this new preview button before posting. In my response to Min I made three mistakes.

“v and q is not fixed,” should be: v and q ARE not fixed;

“so a fixed q is also obviously out,” should be: so a fixed V is also obviously out (v for velocity);

and: “fiscal policy and regulatory intervention is also necessary,” should be: fiscal policy and regulatory intervention ARE also necessary.

I’m going to use the preview button now.

Comment re Kid Dynamite and JKH – China exchanging real assets for financial assets (Feb 18, at 1:45):

The US government can set strict limits on the Chinese ability to do this asset swap. A few years ago a Chinese state owned company tried to buy the 11th largest US oil company, Unocal. This very large purchase, or asset swap, was not allowed. The US is sovereign in its currency and in what it allows people who hold its currency to do with it within its borders. The same applies to all sovereign countries.

Dear Bill,

Quote: “If China think it now has leverage power of the US government then they are stupid or the US government is stupid or both.”

Perhaps the problem is that no gov’t in existence today (that I’m aware of) is designed to operate in a fiat monetary system. All of them were conceived with respect to a gold standard.

–Phil

Interesting observation about China and US Treasuries:

China Sells Treasuries… or Did They?

Perhaps the problem is that no gov’t in existence today (that I’m aware of) is designed to operate in a fiat monetary system. All of them were conceived with respect to a gold standard.

The problem is that they continue act as if they were financially constrained by a convertible fixed rate currency regime instead of recognizing that the world is now on a non-convertible flexible rate regime. Mainstream economics also has not caught up, so policy-makers are still operating under this illusion. Much of the Fed’s literature on its operations has not been updated to reflect this change either.

The task of MMT is educate how the current monetary regime actually functions operationally and to show what this implies both theoretically and relative to policy-making. So far it hasn’t gotten through, and a lot of what is bandied about by so-called experts is nonsense operationally. It’s not reality-based.

I get stuck on “exports are a cost”.

Trade involves exchanging resources for currency. Fiat currency can be increased at will. Resources are irreplaceable and can be depleted.

This is a problem particularly for countries that relying on exporting resources, like Australia, Canada, the petroleum producing nations, and many emerging nations. Resources are basic for an economy, and they are real rather than merely nominal.

GYSC Maybe home prices are still too high and the “how” of supporting them, transferring the debt onto the public balance sheet, has nothing to do with whether this is a goal worth chasing.

The problem is that if the government follows a policy of liquidationism, then asset values with debt attached to them fall so fast that the debt blows up, and in the final cycle of a financial cycle in which Ponzi finance dominates, the whole house of cards will collapse resulting in a depression. The US and world are not out of the woods on this yet. There needs to managed deleveraging, with government picking up the slack with respect to plunging spending power (nominal aggregate demand) that results in an output gap, rising unemployment, forgone opportunity, and social instability.

digital cog You briefly mention the problem of cost shock driven inflation, as opposed to demand driven inflation. It would be interesting to hear your views on how best to conduct policy under such a cost shock.

Good question. How would MMT deal with the resulting stagflation, as happened in the 70’s, differently from Volcker’s tightening short terms rates and inverting the yield curve. A lot of people ask this. Maybe that’s a separate post.

Tom, what about countries that are exporting things besides natural resources? China’s export regime has allowed it to develop a large manufacturing sector. This has certainly proved to be beneficial, even if it has come at the cost of decreased consumption for much of the population. On the other side of the world the United States’ reliance on cheap imports from China has been a major contributing factor to the hollowing out of our manufacturing sector. Isn’t that a cost? Does MMT deny the current imbalances in world trade have real consequences for the economy?

The kertuffle over China $ reserves is pretty pointless.

Countries accumulate foreign reserves for later use, such as:

1. Defend their currencies.

2. Buy resources such as petroleum and materials for domestic production.

3. Invest in foreign countries.

Keeping funds in foreign reserves is like keeping funds in the banks or government securities. It’s just storage for later use. There are plenty of uses to which China can put its reserves and is constantly doing. It won’t have keep such a large store of foreign reserves when its domestic economy matures. Right now, the amount gained from its predominantly export economy has to be managed carefully. China has to control how much is repatriated to prevent inflation.

“If China think it now has leverage power of the US government then they are stupid or the US government is stupid or both.”

I know what I’m betting on…

TH said:

“and in the final cycle of a financial cycle in which Ponzi finance dominates, the whole house of cards will collapse resulting in a depression”

Well at least we agree that Ponzi schemes can collapse!

Thanks.

Greetings all,

Bill, I just wanted to thank you for this site. Your daily writings are so educational and prolific. I”ve been trying to point as many readers from other financial blogs as possible in your direction. I’m curious if any of you have knowledge of any elected or unelected officials out there who actually understand how our monetary system works?

Thanks

China has been a major contributing factor to the hollowing out of our manufacturing sector. Isn’t that a cost?

Comparative advantage. Do US workers want to compete for wages with Chinese workers. I don’t think so. So what’s the alternative? Tariffs? What about WTO? Also, why should US workers be privileged above other workers in the world that need work?

Lots of questions like this that need to be answered and a lot of that is political, not economic. Economically, the US needs to shift its workforce so that it is increasing comparative advantage through investment in the appropriate areas, including human resources, not competing with cheap labor in emerging nations. That’s a no-win game.

From the economic vantage exporting resources and goods is a cost. Importing resources and goods is a benefit. Exporting dollars in a fiat system is no big deal. If the CAD become a concern, then the fx rate drops, favoring exports and the balance resets. And why would the US want to import fx, when it is the issuer of the global reserve currency?

I’m curious about where the two percent figure for determining “full employment,” comes from.

There are three kinds of unemployment:

Cyclical – caused by the business cycle according to the mainstream, and inflation targeting using unemployment as a tool (NAIRU) according to MMT. Some industries like construction are cyclical. They could be gainfully employed in government projects under the Job Guarantee, for instance.

Structural – caused by obsolescence, automation, etc. For example, workers who are permanently displaced due to changes in the economy and need to retrained, like the former employees of buggy whip and horseshoe manufacturers when the auto came into vogue. These workers could be employed through the JG, too, instead of remaining unemployed long-term.

Frictional – people temporarily unemployed, usually voluntarily, e.g., transferring from one position to another. These people are not looking for employment and would therefore be self-excluded from the JG.

Frictional unemployment is estimated to be about 2%. MMT excludes frictional unemployment in figuring full employment.

Re Exports being a cost; certainly exports are a cost but for Canada as a result of its colonial past and the neo-colonial mindset of current decision makers (and many others) there are few alternatives in the short run. Canada devastates its forests, pollutes the air with greenhouse gases to extract and process the tar sands, and pollutes the soil and water to produce mining products, mostly for foreigners. It enables Canadians to get flat screen TVs, foreign automobiles, computers, etc. It also produces many many thousands of jobs in isolated communities where there are few other options for work.

“Comparative Advantage”??? – a nice neoclassical theory – I am kind of surprised that this concept would be mentioned favorably. Comparative advantage has severe limitations in today’s world. We are talking trading small scaled items such as services for larger scale items such as manufacturing. That is a losing scenario on many levels especially in the form of wages for U.S. workers which is very much an economic issue.

In the U.S. there are significant costs to ‘free trade’ and again how is it that exports is a cost – Caterpillar would beg to differ with idea that exports are a cost.

Please forgive me, I should mention the costs of ‘free trade’ or a trade deficit like the one U.S. has: 1) job losses; 2) lost output growth; 3) lost competitiveness; 4) lost investment (as multinational corps. move investments offshore).

In the U.S., the theory was cheap imports would ameliorate the effects of stagnate wage growth. But the prices of cheap imports keep raising faster than wages and so what made up the difference – consumer debt and a lot of it. I am sorry, I digress.

Dear Bill,

This post may be slightly off-topic because I will try to address certain areas which may be marginal to MMT proper but in my opinion this context is relevant and these issues need to be addressed otherwise MMT scholars will make an easy target to their ideological enemies.

I believe the main reason why some economists and people reject MMT is not because MMT violates accounting principles. It is obvious to me that debt financing of budget deficits is based on arbitrary assumptions. The system to some extent has been designed like this and to some extent has evolved. These arrangements may serve interests of some social groups by providing a very useful vehicle to redistribute income – the debt which is also an income-generated asset.

Does anybody assume that people who work for GS are not intelligent?

However not every investor is a bankster and people may fret about the value of their superannuation savings. The main reason is that people in general intuitively think than governments should not create money is because people believe that in general governments do not create value. Governments can redistribute value however this in the most of Western countries is considered to be bad. This is how we WANT to think about money. Money should in theory reflect real value (goods and services) produced by market participants. The number of tokens should reflect the value of current and near future goods and services. Of course this ignores the reality of credit money creation and the reality of financial markets – the very existence of the great global casino.

That’s why even if certain facts mentioned by Bill and the others are indisputable (like the breakdown of money multiplier) the main principles of MMT (for example that deficit spending is required to create net financial assets of the private sector and therefore in some cases is desired) will never be accepted by people who BELIEVE in free markets and who HATE the institution of the state managing the economy. (Yes I know that these so-called free markets may be more than free for some participants like investment banks and big corporations and less than free for workers or unemployed. But true believers in neoliberal ideology usually don’t want to see this ).

The bottom line is that you cannot argue with the opinions based on faith.

There is another group of people who do not subscribe to MMT that is people with engineering background. I may belong to this group. To me there is something dodgy in the assumption that flows can remain unbalanced for a long period of time without causing an overflow. But let’s save this point for another discussion.

The third group of people (to which I also belong) who will never be convinced to the economy being run directly by the state for a long period of time are people who lived in a communist society and who remember that similar solutions were already implemented and failed. I would not easily dismiss points raised by VK on Steve’s forum in regards to long-term effects of low unemployment policies.

I will never forget several visits in the early 1990-ties to the regions of Poland where state owned or collective farms disintegrated and where I saw real poverty. The descendants of serfs living like serfs. “The landlord’s dog bit him but he didn’t complain as he could have lost his job” – this was real…

These people who lived there had been mostly “hidden unemployed” during the communist era. Replacing unemployment by hidden unemployment is in my opinion not a solution. In my opinion the unemployed people need to be given a helping hand and retrained to do something really useful rather than just given “a” job.

When the system crafted by luminaries like Oskar Lange and Michal Kalecki finally collapsed in 1989 with a hyperinflationary thump these people were left basically outside of the new system. They had no useful skills and they were demoralised with the communist mentality (“the state has to look after us and we don’t care”) and often addicted to alcohol.

Here is a brief document describing that context: http://www.iiasa.ac.at/Research/ERD/net/pdf/kowalski_1.pdf

These people were true victims of the both systems – the fallen communist and the new neoliberal one. These few trips opened my eyes and lost my faith in neoliberalism. But a system where the state drives the economy is not a long-term solution either. It is only good for a war-like period but it degenerates very rapidly and becomes corrupt.

I will repeat – these people who lose jobs must be given a hand by the state. But I think they have to be retrained and acquire new skills – not just be given “a” job. In Poland they were given just enough money to survive – a dole. As a consequence about 2 million people left the country. The society is still I affected by this experience – nearly 20 years after the transition happened.

If the current political system in the US is corrupt (the most of visitors to this site wouldn’t question this) why can we assume that the system where the state directly creates demand will be less corrupt? Just imagine lobbying for freshly printed money by all the interest groups…

I have a few more issues in the context of foreign traded / mercantilism and in regards to the transition from the current system suffering from debt deflation to the system proposed by MMT scholars (especially the response to push-type inflation and stagflation) but let’s save them for later.

I believe that application of MMT in some form is inevitable due to the collapse of the current global order caused by the excessive private and public debt but the printing press may not be used for advancing social progress at all. This tool is most often used to pay for military expenses if the budget deficit becomes too large.

(By excessive public debt I mean debt excessive in the environment where budgets are constrained by borrowing on the markets – this will collapse for sure one day).

Finally I believe that inflation which will downsize the real size of debt (and assets) in relation to GDP is the only alternative to a deflationary collapse. But the growing role of the state in directly creating demand may lead to the evolution of the system towards something looking like the Venezuela if not Cuba.

Dear Bill, please do not brand me a neoliberal. I am quite sceptical to any theory which offers easy-looking solutions. It is not my fault that I was born in a communist country and I simply have personal experience from living in a fiat monetary system (almost without credit money) where the state was not constrained by the borrowing in financing their deficits. Yes I know that MMT is not socialism (it does not include central planning, etc) and we are now older (and wiser) but in this case why did you mention Lange and Kalecki? Aren’t you aware of the horrible effects of implementing their ideas? Why did they (the communists) shoot workers in 1970 in the city where I lived? Because of the friction in the price adjustment process?

I believe that MMT is a very valid contribution but we have to put it into a wider historical context. I don’t believe that just spending money to create aggregate demand is enough…

Kind of on topic- I think most of you will enjoy the following “keynes and Hayek Gangster Rap” for a pretty good intro in to economics.

http://www.boingboing.net/2010/02/16/keynes-and-hayek-gan.html

Bill (the notorious B.I.L.L) perhaps you need to work on your rapping to get the message to a wider audience.

“The non-government sector cannot create or destroy net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue.”

Although this is self evidently true, I wonder if there is something to be gained by considering the change in distribution of NFA within the private sector from purely horizontal transactions. In particular, looking at the interactions between banks and non-banks, it seems to me that a well-functioning, profitable banking system implies an increase of NFA (banks) over time, as cumulative interest repaid to banks exceeds cumulative bank expenses, and that this increase in NFA (banks) must be at the expense of an equal decrease in NFA (non-banks).

i.e. banks act horizontally as a sink of private sector NFA.

So, in order for NFA (non-banks, private sector) not to turn negative, there must be an external source of NFA in order to restore private non-bank balance sheets. This would have to arise from a vertical transaction.

Hence, it seems to me that even with G=T (supposing a closed economy), there is a tendency for NFA (non-banks) to become drained via interaction with the commercial banking system, and so a government deficit is required simply to keep private non-bank NFA from falling, let alone allowing the private non-bank sector to net save, which would require an even greater deficit.

Am I off base here?

I see a number of comments to the effect that China has been able to develop a manufacturing base thanks to the ability to export its output to the US. But I see no logical connection: there would be nothing to stop China from developing a manufacturing base from products which it sells to its own people. Perhaps, given the income differential, exports to the West have catalysed the process. Fine. But could we actually rebuild our manufacturing industry if we curbed Chinese imports. Or, to consider another “solution” frequently advocated: would a big RMB revaluation solve America’s China-trade “problem”? Well, it might hit China’s exporters (and also, inevitably, its workers) hard. Multinationals might migrate to other low-wage countries; American importers might seek other sources of supply, in other corners of the Third World. But this much is sure: Not a single low-wage job would return to the United States. So, American consumers could be harmed, while American workers wouldn’t be helped.

At the turn of the 20th century, about half of the American population was engaged in the production of food. Now it’s around 1% and we produce more of it. Should we have fretted about the loss of agricultural jobs? What’s wrong with service jobs? Is working in a steel factory or a car plant really something to which American policy makers can aspire? We should specifically focus on creating new jobs, in sectors (including high tech, education, healthcare and energy conservation) that meet national needs and build world markets for our goods. We should rebuild our cities and transport systems, protect our vulnerable Gulf Coast and otherwise get on with meeting the challenge of climate change, rather than trying to subsidise dying industries.

Net exports (NX) and trade are different issues. NX simply considers the flow of resources and goods in and out, and payments in and out. From the economists vantage, trade considers the issues resulting from this flow in addition to the actual transactions, such as worker displacement.

Most economists are in agreement about comparative advantage and free trade being a net positive for the global economy. However, that does not imply that they agree about how this should be pursued. Neo-liberal “free” trade benefits the multinationals, for example. There is also evidence that trade barriers should be introduced gradually and with due consideration of effects between trading partners or regions of different levels of development. Otherwise, imbalances are likely to occur.

But here we are just talking about NX and the relative cost-benefit of real goods and nominal payments. Obviously, if trade involves barter of goods and resources, then the situation would be different.

Dear Marshall,

1. The cornerstone of the Chinese policy was to develop the wide manufacturing base first and then to get into high tech. Getting western companies to transfer technologies was instrumental in achieving the 2nd goal. (remember what Lenin wrote about the capitallist selling the rope?) I travelled there a few years ago and I was in fact involved in a project related to 3G telephony targetting domestic market only (TDCDMA) so this I saw this with my own eyes.

The Chinese are doing both – export-driven development and growing capacities to meet the domestic demand.

When late Paul Samuelson saw this he freaked out and finally admitted a mistake in his free trade theories. The Chinese were only supposed to make plastic boxes not high-tech telecommunication equipment.

It is difficult to directly describe transfer of know-how in monetary terms. But this is a fundamental issue determining their growth and development.

2. I believe we (in the US and Australia) must preserve some manufacturing capacities. The reason is the same as growing rice in Japan – national security.

3. There is an issue I don’t have a solution. There is a lot of unemployed people with IQ around 80-90. They cannot be computer programmers but they have the same human dignity as a guy with IQ 145 (mine is probably much lower). This may be the root cause of higher structural unemployment in the 2000-ties compared with 1950-ties. There was a lot of demand for manual labour then. I believe that aged care and some services may provide employment opportynities for less educated people.

Good points, Marshall Auerback. This is already happening in the emerging nations. China is now outsourcing to Indonesia for even cheaper labor, for instance, as Chinese workers get paid more. Eventually, Africa will come online, too. This creates strains in the poorest countries, too, as the traditional way of life gives way to modernization. So the problems are not just with the developed nations, where the bargaining power of fungible labor is declining. But service jobs, unlike manufacturing, are not as readily fungible because they often must be performed locally. In addition, may jobs are protected by regulations and licensing. This applies between the states in the US, too.

Adam, I’m not criticising China for adopting the approach it has taken in the past. Whether it works going forward is another matter. Worth noting, for example, that during the Great Depression it was creditor nations such as the US, which got hit the hardest, due to the onset of protectionism. And while I’m not a free trade theologist, I can assure you, I wonder whether it should it be government policy to subsidise dirty, repetitious jobs that cannot compete on even fair trade principles? It’s always difficult to say what jobs will replace manufacturing, but my reading of Marx at university and my own experience working a summer job in one of the local steel factories growing up in Canada, tells me that this is not the sort of high quality job that our policy makers should be aiming to reintroduce.

The “progressives” who rail about how we eventually have to get control of the deficits always insist that we have to rebuild our manufacturing base because you can’t possibly just have a service economy.

Why not? Those nice trails which restored the spectacular walk from Coogee to Bondi in Sydney represent precisely the sort of work that would be gratifying and create huge social benefits.

Tom, lots of good points, as you always make!

Dear Tom and NKlein1553

NKlein1553 asked:

Tom replied with the standard taxonomy of unemployment – cyclical, structural and frictional – which is widely used although hardcore mainstreamers always claim the decomposition is invalid because all unemployment is voluntary – you can cut your wage (addressing the cyclical); you can move or you chose to not invest in skills (structural) and friction is voluntary as Tom notes.

The taxonomy is somewhat problematic however particularly the structural component.