These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

The US dollar is losing importance in the global economy – but there is really nothing to see in that fact

Since we began the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) project in the mid-1990s, many people have asserted (wrongly) that the analysis we developed only applies to the US because it is considered to be the reserve currency. That status, the story goes, means that it can run fiscal deficits with relative impunity because the rest of the world clamours for the currency, which means it can always, in the language of the story, ‘fund’ its deficits. The corollary is that other countries cannot enjoy this fiscal freedom because the bond markets will eventually stop funding the government deficits if they get ‘out of hand’. All of this is, of course, fiction. Recently, though, the US exchange rate has fallen to its lowest level in three years following the Trump chaos and there are various commentators predicting that the reserve status is under threat. Unlike previous periods of global uncertainty when investors increase their demand for US government debt instruments, the current period has been marked by a significant US Treasury bond liquidation (particularly longer-term assets) as the ‘Trump’ effect leads to irrational beliefs that the US government might default. This has also led to claims that the dominance of the US dollar in global trade and financial transactions is under threat. There are also claims the US government will find it increasingly difficult to ‘fund’ itself. The reality is different on all counts.

All central banks hold reserve currencies which allow them to make foreign exchange transactions that influence the movement of exchange rates.

Under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, the capacity of a central bank to defend its currency against depreciating forces depended on the quantity of foreign reserves it held.

That proved to be a major shortfall of the system and ultimately led to its demise.

If a central bank did not have sufficient quantities of foreign currency reserves then it had to seek loans from the IMF under that system and/or devalue its currency under the Bretton Woods protocols.

With the flexible exchange rate system now dominating, central banks still maintain foreign currency reserves for a range of transactions including the smoothing out of major currency movements.

The US dollar is the dominant reserve currency and nations hold reserves of that currency to allow them to transact in trade given that a significant proportion of global commodity trade is denominated in the US dollar.

Having stores of US dollars means a nation does not have to sell its own currency for the US dollar in order to transact in global markets, which provides a modicum of stability to its own currency.

The IMF publishes a dataset – Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) – which allows us to trace movements in the denomination of currencies held in reserve by central banks.

There are some technicalities – such as the difference between allocated versus unallocated reserves – that we don’t have to go into here.

This data is also relevant to a recently released a report from the European Central Bank (June 11, 2025) – The international role of the euro – along with a detailed – Statistical Annex – which traces the “international role of the euro”.

Any hint that the euro would become a dominant global currency is not supported by the data, which shows that the:

… share of the euro across various indicators of international currency use has been largely unchanged, at around 19%, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The euro continued to hold its position as the second most important currency globally.

While the “share of the US dollar” in “global official foreign reserves … declined by 2 percentage points at constant exchange rates, to 57.8%” in 2024, the longer term trends have seen the US dollar’s share decline by around 11 percentage points over the last decade.

In the March-quarter 1999, the US dollar share was 71.2 per cent.

By the December-quarter 2024, it had dropped to 57.8 per cent.

For other currencies (the IMF did not start collecting this data for all countries at the same time):

1. Euro – 18.1 per cent March-quarter 1999; 19.8 per cent December-quarter 2024.

2. Pound sterling – 2.7 per cent March-quarter 1999; 4.7 per cent December-quarter 2024.

3. Yen – 17.6 per cent March-quarter 1999; 19.8 per cent December-quarter 2024.

4. Yuan – 1.1 per cent December-quarter 2016; 2.2 per cent December-quarter 2024.

5. Canadian dollar – 1.4 per cent December-quarter 2012; 2.8 per cent December-quarter 2024.

6. Australian dollar – 1.5 per cent December-quarter 2012; 2.1 per cent December-quarter 2024.

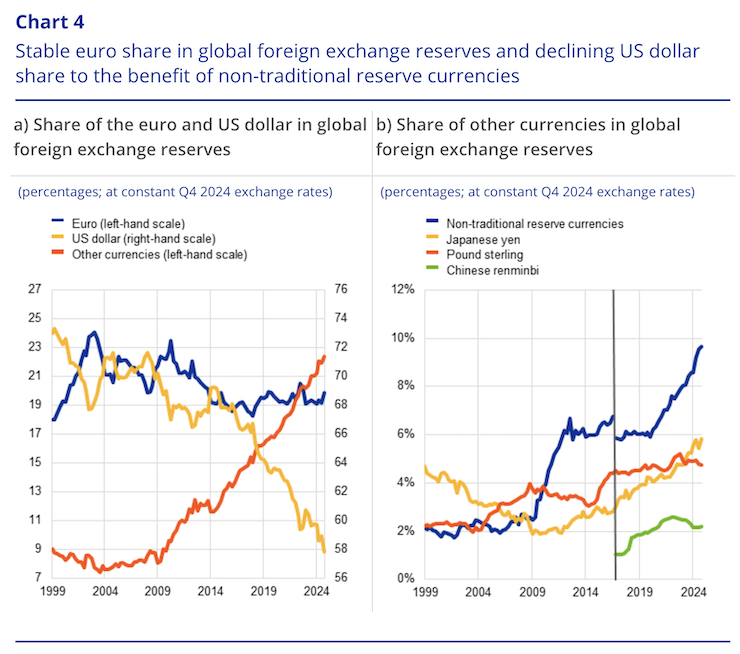

The ECB provide the following graph which shows the shares of various currencies in global foreign exchange reserves.

Being careful not to be confused by the use of the right- and left-hand scales, it is clear that the US dollar has slipped quite substantially and the “other currencies” have increased their importance among institutions that hold foreign exchange reserves.

The “other currencies” include “the Canadian dollar, the Australian dollar, the Korean won, the Singapore dollar, the Swedish krona, the Norwegian krone, the Danish krone and the Swiss franc in decreasing order of estimated importance”.

In terms of the right-hand panel in the graph above, the ECB note that “By the end of 2024 the share of currencies other than the US dollar and the euro had risen to 22.4%, driven by strong gains in non-traditional reserve currencies … its combined share grow by 1.1 percentage points in 2024, to 9.6%.”

Of interest is the fact that the Chinese yuan (renminbi) initially was seen as an attractive reserve currency, its share peaking in 2022.

It has since declined and the most recent report from OMFIF – Global Public Investor 2024 – which studies “global policy and investment themes relating to central banks, sovereign funds, pension funds, regulators and treasuries”, found that:

… Appetite for renminbi has soured. Nearly 12% of reserve managers are looking to decrease holdings in the next 12-24 months.

Why?

This is partly due to relative pessimism on the near-term economic outlook in China, but the vast majority also mentioned market transparency (73%) and geopolitics (70%) as deterrents to investing in Chinese financial assets.

However, the longer-term trends are different.

The survey data shows that:

… over a longer horizon, central banks expect to diversify towards the renminbi. In net terms, 20% anticipate adding to their renminbi holdings over the next 10 years, which is greater than for any other currency. On average, respondents anticipate that its share in global reserves will more than double to 5.6% in the next decade, from 2.3% now.

But that will still not make it a dominant currency.

For both the euro and the renminbi, the global roles played by these currencies continues to be way under the size of the respective economies, which gives people licence to suggest that they will increase their role in global reserves significantly over the next several years.

There is some opinion that Trump’s behaviour will accelerate the trend away from the US dollar.

ECB boss ‘Madame Lagarde’ introduced the ECB Report saying:

… further shifts may be underway in the landscape of international currencies. The tariffs imposed by the US Administration have led to highly unusual cross-asset correlations. This could strengthen the global role of the euro and underscores the importance for European policymakers of creating the necessary conditions for this to occur. The number one priority must be advancing the savings and investment union to fully leverage European financial markets. Eliminating barriers within the EU is essential to enhancing the depth and liquidity of euro funding markets, which is a precondition for a wider use of the euro. The planned issuance of bonds at the EU level – as Europe takes charge of its own defence – could make an important contribution to achieving these objectives.

Note first, that the role of the euro in global foreign exchange reserves has been invariant to the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, which some found surprising.

Lagarde is obviously trying to condition the political debate in Europe in relation to the current arms’ race intentions.

But as I discussed in the recent blog posts – The arms race again – Part 1 (June 11, 2025) – and – The arms race again – Part 2 (June 12, 2025) – the European Commission’s strategy is to sheet the increased debt onto the Member States, which will not turn out to be a successful strategy and may actually lead to a reversal of any sentiment gains with respect to the euro as a reserve currency.

Two factors which can influence the demand by institutions for a particular currency as a reserve are: (a) exchange rate fluctuations, and (b) changing bond yields across nations. The second factor is less of a factor because yields tend to move in concert with economic fluctuations.

However, in relation to the first influence, an IMF report analysing the COFER data (May 5, 2021) – US Dollar Share of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves Drops to 25-Year Low – found that fluctuation in the US dollar since 1999 explains “80 per cent of the short-term (quarterly) variance in the US dollar’s share of global reserves” and the “remaining 20 percent of the short-term variance can be explained mainly by active buying and selling decisions of central banks to support their own currencies”.

Yet, the size of the US bond market coupled with the lack of a significant, risk-free euro bond market means that the US dollar will remain dominant.

The Europeans may long for the euro to become a dominant currency but the nature of the monetary architecture and the obsession with pushing responsibility for debt-issuance on Member State governments and an aversion to issuing EU-level debt backed by the ECB makes it hard for them to achieve their goals.

The hope for the Europeans is that the Trump-induced chaos will compromise the so-called ‘safe haven’ status of the US dollar.

The recent slide in the US dollar exchange rate will see a further decline in the share of the US dollar in global reserve balances.

But the question is whether the tariff hoopla and the rest of the ‘failed state’ meanderings of Trump and his cronies is going to cause a structural decline in the US dollar.

Note: US Border Control officials – I am not planning any trips to the US in the near future!

There is some evidence to support the case that times have changed.

As I noted above, when global uncertainty increases the demand for US-dollar assets (such as government bonds) increase.

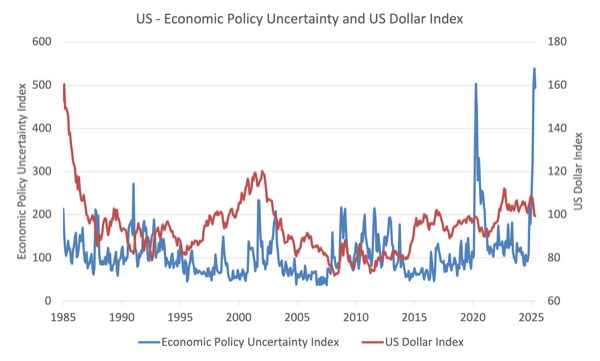

This graph compares movements in the monthly US Dollar Index (DX-Y.NYB) with the – US Economic Policy Uncertainty Index from January 1985 to May 2025.

Prior to 2025, there is a fairly well defined positive relationship between the two – when uncertainty rises, the dollar index rises (the exception being the lagged effect in the early COVID-19 period).

However, in the recent period, that relationship has changed and the Trump uncertainty spike is beyond even the COVID-19 shock and the US dollar index is starting to fall.

These findings are supported by more formal econometric analysis – HERE.

The EPU Index is not available for June 2025 as yet, but the US dollar index continues to fall into June – 2.5 points around since end of May.

The final point today is about what this means for US fiscal policy viability.

One of the accompanying narratives of the declining share of the US in global reserve balances is that the American government will start to struggle to ‘fund’ its fiscal deficit.

These claims which are being regularly rehearsed in the media these days are without foundation.

As regular readers will appreciate, the US government ‘funds’ its deficit in the act of spending, because it is the currency issuer.

No amount of accounting structures that are put in place can change that fact.

When the government instructs its financial agency to credit a bank account to facilitate procurement requirements the number so typed is ‘funded’ at that point.

The number doesn’t reflect taxes or bond issuing revenue.

Those numbers are, in this context, just artefacts of the accounting systems that the government uses to pretend they are ‘spending’ taxpayers or investor funds.

That is not to say that private US traders etc will not be hurt by the sliding importance of the US dollar in global markets.

They enjoy benefits such as an absence of hedging insurance outlays on transactions denominated in US dollars.

Conclusion

But the latest IMF and ECB data and analysis does not suggest these advantages are about to dissipate any time soon, even with Trump going crazy.

And on the claim that MMT is only applicable to the US because of its dominant status as a reserve currency – I discussed that proposition in this blog post – Another fictional characterisation of MMT finishes in total confusion (March 13, 2019).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The “exorbitant privilege” of the US dollar cannot be explained with two or three arguments. It has many.

The main argument is the “de facto” imperial force behind it.

Just look how Trump acts like an emperor.

Look, for example, how he thinks he can order people to buy cars of a certain brand or how he can ignore any accusations of corruption, when he accepts a gift of a jet airplane.

We could go on, but it’s no use keep talking about buffoonery.

The 800 US/nato bases are another argument for the “exorbitant priviliege”.

The dollar dominance was/is imposed on everyone.

Just look at the Saudis back in the 1970s.

The oil trade was imposed on them with the green back atached, so that everybody would need US dollars to buy oil.

Look how, today, the Saudis don’t dare to question anything the empire decides, even if it’s the killing of an entire population.

And, if someone decides to question its dominance, they have the ultimate threat: they can nuke you, just like they did to the Japanese.

In his 2020 book – Covid19: The Great Reset – Klaus Schwab advocates for “permanent quantitative easing” (ie where Treasury never repay the debt they create by printing money), which he asserts is the same thing as MMT. Would you agree that permanent quantitative easing i the same thing as MMT?

Dear Dr Stuart Jeanne Bramhall (at 2025/06/17 at 7:14 am)

Thanks for your comment and question.

Permanent quantitative easing is not the same thing as MMT.

The former involves the central bank buying government bonds and other securities in the various financial markets in return for crediting reserve accounts of the selling bank.

Its purpose is to drive up asset prices and drive down yields along the yield curve – in other words to lower interest rates in the investment region which proponents think will stimulate private investment and hence GDP.

It assumes that governments issue bonds in the first place and run a positive interest rate policy stance.

Core MMT requires the government to issue no debt to accompany any spending in excess of taxation revenue and for the central bank to run a permanent zero interest rate policy stance.

The two things are thus quite different.

best wishes

bill