The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

A lower yen is not inflationary once the adjustments are absorbed

Last Friday (December 5, 2025), I filmed an extended discussion with my Kyoto University colleague, Professor Fujii about a range of issues concerning the Japanese and Global economy. Once it is edited, the video will be available on YouTube. Fujii-sensei is advising the new Japanese Prime Minister and is the author of the ‘Responsible proactive fiscal policy’ slogan that is summarising the shift within the Japanese government from the Ishiba Cabinet and their austerity mindset to the new Takaichi Cabinet and its desire to introduce renewed fiscal expansion. Among the topics discussed: (a) my conjecture that Japan is caught in a vicious cycle of secular stagnation and requires a large fiscal shock to alter the deflationary mindset that has crippled the economy over several decades; (b) the need for tariffs to protect Japanese industry to advance food security (in the face of major rice shortages during the last year or two); (c) whether Japan should participate in Plaza Accord 2.0 (aka Mar-a-Lago Accord) that Trump is demanding China accept; and (d) policy structures that are necessary to reallocate labour from areas of excess (gig economy) to sectors where shortages and bottlenecks are present (for example, Construction), The latter will be essential if the proposed fiscal expansion is to stimulate production rather than prices. For the purposes of this blog post though, we also discussed the validity of fiscal expansion within the context of the yen. Mainstream economists keep arguing that the expansion is not viable given the depreciation of the yen, which they claim has been inflationary. It is a standard argument and I mentioned it in this recent blog post – Panel of Japanese economists mired in erroneous mainstream constructions and logic (November 27, 2025). I consider that issue more today.

What is inflation?

Many people confuse ‘inflation’ with a ‘price rise’, although there is , of course, some correspondence.

Inflation is the continuous increase in the price level of a good or all goods (a composite measure that is).

If the price level is increasing at an increasing rate then we say there is accelerating inflation.

If the price level is continuously increasing by the subsequent increases are smaller than the last then we say there is decelerating inflation.

If the price level is continuously increasing at the same constant rate, then we say there is stable inflation.

Deflation occurs when the price level is continuously falling.

A step increase (or realignment) in the price level does not constitute inflation.

This difference is particularly important when we consider exchange rate movements.

Movements in the yen

The Japanese currency (yen) has depreciated in value significantly since the pandemic began.

The following graph shows the monthly movement in the yen against the USD from 1980 to October 2025.

A downwards movement indicates an appreciation of the yen against the USD and vice versa.

The major appreciation prior to the Plaza Accord in the early 1980s is striking as the USD struggled to hold value.

I wrote about that in this recent blog post – Talk of a Plaza Accord 2.0 should heed the lessons of Plaza Accord 1.0 (December 1, 2025).

However, it is the recent period that is of interest in this discussion.

The most recent yen deprecation began in February 2021 (in January 2021 the yen was at 103.69).

Inflation didn’t start to accelerate until early 2022.

Putin invaded Ukraine for the second time in February 2022, after previously beginning hostilities in 2014 (Crimea annexation etc).

OPEC oil price hikes began in earnest in November 2020, rising from USD36.152 per barrel to USD114.83 per barrel at the peak in May 2022.

It was the energy price hike that precipitated the rise in inflation, followed by supply constraints that followed the relaxation of Covid restrictions and the Putin folly.

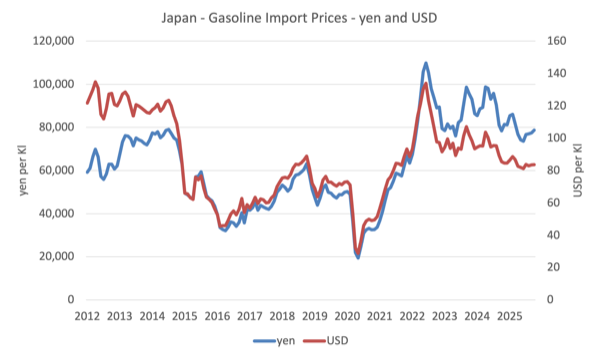

The following graph shows the trajectory of Japanese imported gasoline prices in both yen and USD terms.

The movements are mostly motivated by global factors but we observe in the period following the OPEC hikes from 2020 to 2023, the impact of the yen depreciation (blue yen line deviates from the USD red line).

So the yen equivalent of the USD gasoline price has diverged even though both are trending downwards.

When the Bank of Japan decided to hold interest rates constant in the face of the inflationary pressures, while the other central banks were vigorously hiking rates, it knew that there would be an impact on the exchange rate.

When the Federal Reserve Bank started hiking interest rates in March 2022, the yen stood at 118.5 against the US.

Since March 2022, the yen has depreciated around 17.5 per cent against the USD, a significant parity shift.

In the last year, the mainstream ‘experts’ claim that the depreciation proves that Japan’s continuing fiscal deficits and the high public debt ratio are being rejected by the financial markets.

However, other factors have been at work.

After the – 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami – known as 東日本大震災 (Great East Japan Earthquake) – the currency appreciated because it was expected exposed insurance companies would have to repatriate foreign currency assets.

That didn’t turn out to be the case, but the currency appreciated nonetheless, even though monetary and fiscal policy is largely unchanged from that period to now.

If you examine the graph, you will see several periods of appreciation, especially since the 1990s, even though macroeconomic policy has been consistently expansive over this entire period (bar brief periods).

None of these events had much to do with domestic policy.

For example, we might ask what was going on between November 2011 and August 2015, when the yen depreciated significantly against the US dollar, giving back the shifts that occurred during the GFC?

Did the yen suddenly become an unsafe currency?

And if it did, why did the currency then start appreciating again up to the period when the central bank interest rate differentials began to widen because of the different responses to the inflationary pressures?

Net exports went into deficit in mid-2011, as exports growth faltered, and did not return to surplus again until the September-quarter 2016.

It was trade movements that drove the exchange rate changes.

All through these episodes, there have been continuous Japanese fiscal deficits, a rising public debt ratio, a zero-interest rate monetary policy, and large quantitative easing purchases of government debt.

The depreciation that was associated with the ‘Three Arrows of Abenomics’ which aimed to renew economic growth and break out of the deflationary lock is an interesting case study.

It is well understood that the Abe government from 2012 implicitly wanted the yen to depreciate significantly as part of his plan to reflate the Japanese economy.

Before his election, Japanese manufacturing was struggling against the high yen value, which reinforced the deflationary environment and made it difficult to promote wages growth.

The major shifts in the yen value have mostly reflected global shifts in activity and policies and speculative efforts to profit from them.

The base case is that the yen is a safe-haven currency.

There is an on-going debate as to the extent that the so-called ‘carry trade’ have driven the movements in the yen recently.

The mainstream explanation is that the interest rate differentials have motivated investors to shift yen, borrowed at low rates, into other currencies in search of better yields.

While there is no doubt this explains some of the movement, a more plausible explanation is that the shift of the trade balance to deficit in recent years promoted weakness in the currency (excess supply of yen to the market).

The yen depreciation that began in early 2012 coincided with the tsunami that shut down the nuclear power plants and increased Japan’s energy imports for power generation, driving the trade balance to deficit.

The yen recovered with the return of trade surpluses, followed by depreciation as COVID cut into exports and trade went into deficit.

Once the trade balance returns to surplus, the yen will strengthen, driven by trade flows.

The current situation

The mainstream narrative that is repeated often is that the depreciation is inflationary.

The claim is that depreciation increases the yen equivalent of foreign prices, which importers then pass on to final consumers in the form of higher domestic prices.

How fast that takes place following an exchange rate change is determined by so-called ‘exchange rate pass through’.

If the pass through is 100 per cent then all the currency value effects become reflected in the final price.

If it is rapid, then the impact is immediate.

Research is mixed with respect to Japan but most leans towards relatively high rates of pass through over a relatively short period.

During the recent inflationary episode, the Japanese government subsidised importers which reduced the pass through as margins were absorbed.

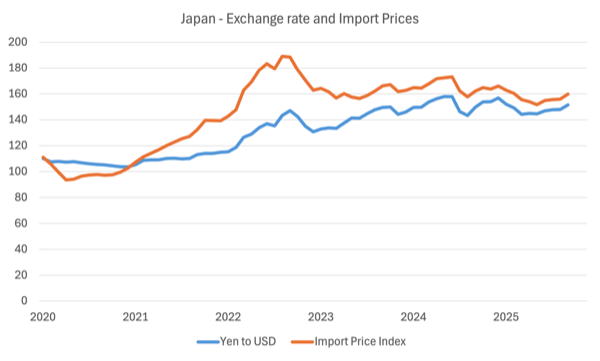

The following graph shows the evolution of the yen parity and import prices (base year 2020 = 100) in Japan from 1980 to October 2025.

There is some correspondence between the trajectories.

The question at present is whether the exchange rate is driving the inflationary process.

The answer is No!

Reflect back on the opening points in this blog post before you proceed.

If we examine the most recent period (see next graph) we can see that the yen has stabilised at its new lower level against the USD – averaging 148.98 since June 2023.

You can also see that import prices have stabilised at the new higher level after the rises from 2020 to 2023.

The point is that the inflationary impacts, if any, of the higher import prices and lower yen have now been mostly absorbed into the price level.

There are no further inflationary impacts coming from the currency.

Sure enough, Japanese consumers are now paying higher prices for imported items.

But that upwards adjustment has now largely dissipated.

And if the Takaichi expansion includes subsidies to households (for example, the government has already announced a 20,000 yen cash payment to all children under the age of 18) and corporations to allay some of the higher price burdens, then the CPI will fall quite substantially.

Conclusion

One of the things I noticed when I first went to our local supermarket in Kyoto in September was the dramatic rise in price for table rice.

Even though rice consumption by Japanese households has fallen dramatically over the last 50 or so years, it remains a major part of the diet.

Rice policy in Japan is another story altogether and I will deal with it another time.

But for those who think that the lower yen continues to be inflationary – the message is to think again.

The price level is heading down not up given current trends and the inflationary impacts of the depreciation are all but gone.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What a great example of a complex system analysis delivering an understanding that is counter to the erroneous, simplistic mainstream, linear, rule of thumb thinking that a fall in exchange rate = inflation. Is it no wonder that neoclassical economists are the snake oil salesmen of the modern era which peppers Joe & Josephine public with simple mantras (maxed out the public credit card, leaving the debt to the grandchildren, etc.) almost straight out of Animal Farm? Daniel Kahneman is well worth a re-read.

Again, as ever, mainstream economics eliminates the vector of time in their analyses of macroeconomics and goes straight to an ingrained (propagandised?) heuristic.

The deep state (private capital elites, who finance media/lobby groups/think tanks) will always get their way.

Politicians are just used care sales people to me since learning MMT.

I think MMT exposes them

Neil WIlson said on reddit:

https://www.reddit.com/r/mmt_economics/comments/1lcls3b/comment/my84t3t/

“Why would a box of apples suddenly exchange for fewer grapes simply because some spivs decided to play silly games with numbers on a computer? There has been no change in the productive mechanisms that produce apples or grapes, therefore the ratio of apples and grapes on the world market will tend to stay the same and be arbitraged towards that. That’s why ‘devaluations’ in fixed exchange rate systems never work. “

Most of us who are interested in macroeconomics probably understand the technical arguments for saying that an increase in the price level shouldn’t necessarily be regarded as inflation. Price rises caused by a one off reduction in the exchange rate is an example of this.

The problem, politically, is that it will still feel like inflation to most people who aren’t particularly interested in the technicalities. They won’t be waiting until “the adjustments are absorbed” before expressing their displeasure.

Workers will demand higher wages to compensate. Employers will try to raise prices further to pay the higher wages.

Politicians will always be keeping a closer eye on the exchange rate than economists would like!

Peter,

The problem is that politicians don’t understand inflation, the same as workers, unions and employers. Why? Because of poor economic education at universities that is perpetuated and reinforced by the media.

@ Wayne,

You’re right that mainstream pushes a version of macroeconomics that is incorrect.

But this is only a partial explanation. Most voters haven’t had any economics education at all and,unfortunately, in my experience, they aren’t particularly interested in it.

This is the reality that politicians have to contend with.

What matters for people in general is what buying power their income has. How the term “inflation” is defined in economics is irrelevant for the consumer, but they have learned that less buying power is caused by inflation.

If the prices rise on necessities needed to live your life, you are worse off; whether that is caused by inflation or one-time adjustments is not so important. You have to buy less of something to keep your budget balanced. Or maybe you can replace it with something else without losing quality. But in today’s world many necessities are imported and cannot be replaced with stuff domestically produced.

What does “absorbed” mean? Getting used to less buying power?