Regular readers will know that I hate the term NAIRU - or Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment - which…

Two diametrically-opposed approaches to dealing with inflation – stupidity versus the Japanese way

Well things are going to get messier with the decision yesterday by the OPEC+ cartel to significantly reduce the oil supply and push up prices. On the one hand, when OPEC was first formed and pushed prices up, while there was significant disruption to oil-dependent nations, the substitution that followed (home oil heating abandoned, larger cars replaced by smaller cars, etc) was ultimately beneficial. So given that we need less cars on roads and less kms travelled by cars, one might consider the move to be fine. But given the way the central banks and treasury departments around the world are behaving at present, the short term impacts of the OPEC+ decision will be very damaging. How citizens endure whatever extra inflationary pressures that might emerge will depend on the fiscal and monetary policy responses. We have two diametrically opposed models: the one that most nations are following (hikes and austerity) versus the Japanese approach. I explain the difference below and predict that the latter will deliver much better outcomes for the people.

OPEC supply cuts

The plus in OPEC is the non-OPEC oil producing countries, including Russia, who agreed to go along with supply cuts in 2016 proposed by the 13 OPEC nations.

According to the – Oil Market Report – September 2022 – published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), Russian oil production is expected to decline further by the end of this year and the EU embargo binds.

However, even with that reduction, the IEA estimates that:

Such losses would still leave the market oversupplied in 2H22, by close to 1 mb/d, and roughly balanced in 2023.

The IEA also estimates that the OPEC 13 countries have spare crude oil production capacity of around 2.75 million barrels per day, while OPEC+ nations have spare capacity of 0.51 million barrels per day.

So the decision to cut production by 2 million barrels a day is not quite the squeeze that the sensationalist headlines are suggesting.

The cuts are in the context of an already oversupplied market.

How much prices rise is a guess at this stage and any price rise will of course help Russia, which is facing significant cuts in volumes sold.

Whether we can interpret that as OPEC ditching the US and cosying up to Russia as a new ally is the domain of propaganda.

It looks to me rather a decision based on price ambitions rather than some strategic geo-political switch by the main oil producing nations.

OPEC is seeing the madness of central bankers trying to drive their economies into recession as fast as they can and knows that in a state of (already) oversupply, a recession will worsen the excess and drive prices below what they want to receive.

The purpose of a cartel is to control prices to achieve income aspirations.

And with the EU and the US now colluding to set price caps, it has become one ‘cartel’ (informal) on the demand side against another cartel (OPEC) on the supply-side.

We should not be surprised therefore for the supply-side to rule.

But if the OPEC logic that higher interest rates have forced their hand is accurate, then we have the beginnings of a sort of vicious cycle:

Oil supply withdrawal -> Oil price hikes -> Higher inflation rates -> Higher interest rates -> More supply withdrawal.

And so it goes.

That will be a very ugly short-term outcome if it occurs.

But the IEA September oil market report tells us that many of the OPEC members are not producing anywhere near their targets (and have excess capacity), so the price impacts of the decision to withdraw supply may be rather small.

To some extent, it will depend on whether China abandons its (excellent) zero Covid strategy.

At present, that is keeping the oil demand side more muted than otherwise.

Overall, the concentration on energy issues at present are focusing our minds on shifting away from fossil fuels, which over time will be an excellent outcome.

In the short-term, the inflationary impacts so far arising from the OPEC decisions (as well as other sources – Covid, War in Ukraine) – have invoked mostly harsh contractionary fiscal and monetary policy responses.

When I say contractionary monetary policy responses, I am referring to the mainstream logic that says rising interest rates are counter-inflationary.

We know there is evidence to support the contrary hypothesis.

But one country stands out from the rest in this regard.

It is the country I am currently working in and studying closely.

Fiscal and monetary policy comparisons

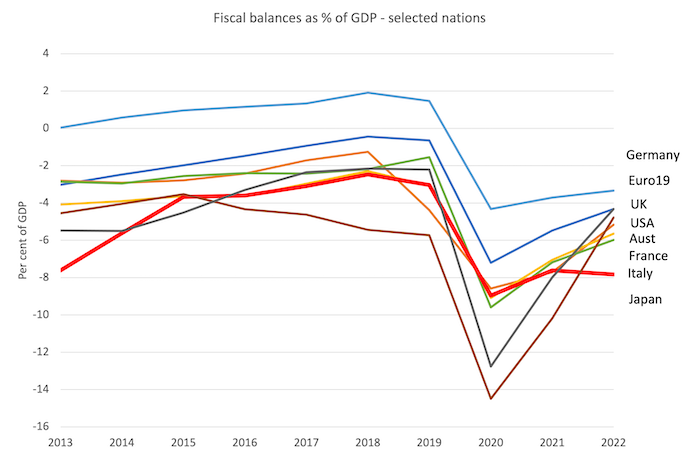

The following graph shows the movement in fiscal balances as a per cent of GDP for selected advanced nations and the Eurozone in total from 2013 to 2022.

The country designations are in order of where the fiscal balance is currently estimated to be sitting (not enough space to align them next to the relevant lines but you can trace the lines relative to nations easy enough).

The Eurozone Member States as a whole (dominated by Germany) shifted the least during the pandemic and the degree of fiscal support provided was significantly different to the English-speaking west.

The UK and US swung the most during the pandemic but the degree of fiscal contraction since 2020 has been substantial.

The standout is Japan at the other end of the scale – its fiscal balance did not fluctuate as much during the pandemic as say the US and the UK, but it has held its fiscal support at around 8 per cent of GDP to the current period, in contradistinction to the other nations.

The other standout in Japan’s case is the conduct of the Bank of Japan which maintains a minus 0.1 policy target interest rate.

It also continues to purchase large quantities of Japanese government bonds.

Consider these facts:

1. Since December 2012 (when Shinzo Abe took office), the Bank of Japan has purchase 165.9 per cent of the total bonds outstanding.

That means it has bought all the new issues and then some.

2. Since the pandemic began, the Bank of Japan has purchased 41 per cent of the change in outstanding government debt, more or less maintaining its overall proportionate holdings.

The following graph shows the Bank of Japan’s holdings of government debt since 1990.

Japanese exceptionalism

Japan has faced the same global supply pressures that have pushed the current inflationary impulse.

But while other nations are busily engaging in fiscal austerity in the misconceived need to ‘repair their budgets after the pandemic’ and their central banks are hiking like crazy, Japan has held its nerve with respect to interest rates and has been particularly active in using fiscal policy to reduce the cost-of-living pressures on ordinrary Japanese citizens.

A world away in other words from elsewhere.

I wrote about that a few months ago – Why has Japan avoided the rising inflation – a more solidaristic approach helps (July 4, 2022).

On Monday (October 3, 2022) the Prime Minister Mr Kishida, with his face mask responsibly on in an indoor setting, announced in the new (210th) Diet (Parliament) that the government would introduce what he termed “unprecedented and drastic measures” to address inflationary pressures, including policies to reduce electricity bills for both households and businesses.

What, fiscal austerity or pressuring the Bank of Japan to push up interest rates?

Quite the opposite.

The Government will launch a series of fiscal spending initiatives this month.

You can find the full transcript of his speech here – 第二百十回国会における岸田内閣総理大臣所信表明演説 (Policy Speech by Prime Minister Kishida at the 210th Session of the Diet).

The PM told the DIET (my translation):

1. “We will do everything in our power to respond to the current high prices and revitalize the Japanese economy”.

2. “The Covid crisis, the energy and food crisis, and the climate crisis caused by global warming have plagued the world for the last two and a half years.”

3. “Japan has overcome the corona disaster and normalization of socioeconomic activities is progressing. However, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, soaring energy and food prices due to the yen’s depreciation, and fears of a global economic recession have become major risk factors for the Japanese economy.”

4. “Last month, we finalised additional measures to curb rising food and gasoline prices. We have taken urgent support measures, especially for low-income households whose financial impact is particularly large.”

5. “we will design comprehensive economic measures this month, and will do whatever it takes to protect people’s lives and business activities from these high prices.”

6. “measures have already been taken to keep the import wheat prices … unchanged from October onwards.”

7. “A major issue … is the risk of a sharp rise in electricity prices. We will take unprecedented and drastic measures that will directly reduce the rising cost of electricity for households and businesses.”

And more.

You get the drift.

He also spoke of managed wage increases within the public and private sectors to deal with the historical problem of low wages growth and investments to raise productivity and economic growth.

Compare that narrative with what we hear from the English-speaking leaders – ‘budget repair’, ‘heaving from trillion dollars of debt’, ‘fiscal policy has to be restrained so interest rates don’t keep rising higher’, ‘interest rates will rise until we stop inflation’, etc.

Light years apart.

You can also find the documents relating to these new measures at the Cabinet Office site – HERE (released October 5, 2022 and written in Japanese).

The Prime Minister noted that:

Today, we discussed the formulation of comprehensive economic measures and related investment in people and GX (Green Transformation). In order to put the economic measures on a high growth path, first of all, we will take all possible measures to support people who are in a difficult situation due to soaring prices. In addition, in order to achieve continuous wage increases that will not be outdone by price increases, we will strengthen support for reskilling to move to growth areas and support for small and medium-sized enterprises in light of the minimum wage hike from October. At the same time, under the new capitalism, we will accelerate public investment, which will serve as a prime mover in priority areas, and further expand private sector investment.

Already, we have seen the Japanese government pay subsidies to petrol wholesalers which has kept petrol prices much lower than otherwise.

While the full detail is yet to be announced, it is likely they will use the same approach for energy suppliers.

Conclusion

It is very interesting living and working in Japan at present and seeing these policies close up.

Coming from Australia, where the RBA has been damaging the prospects of low income home owners and would-be home owners after promising they would not raise interest rates until 2024 and listening to the Treasurer bat on, on a daily basis, how we must tighten our belts and have a national conversation about how we will pay for things, Japan is like a breath of fresh air.

They talk about protecting the citizens and using the currency-issuing capacity of the Japanese Ministry of Finance and Bank of Japan (consolidated) to do whatever it takes to protect them against inflation, while the supply constraints take their time to work through.

An amazing difference.

And Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) will tell you which approach will deliver better outcomes for the well-being of the people.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Japan didn’t exactly followed the desindustrialization path of the western world, and so their monetary and fiscal policies are seen as adjustements to markets dynamics, turned accute by their big neighbour, China.

How can you keep the lead in industrial production, if your neighbour can sell what you are trying to sell, several times cheaper?

But, production costs in China are going to rise up, if they intend to take the lead.

In fact, you can manufacture socks, taking paisants to the production line, but you need skilfull workers if you intend to manufacture cars with Japanese quality standards.

Japan did transfer many industrial production to EMs, but keeps a lot of the high tech in Japan.

Germany also tried to hold on to their best industries, but now they seem to be catching up, as production costs in Germany are skyrocketing and many industries will close and transfer production to China.

The EU blob has it’s own “China” at the back door, but it keeps bemusing 2022 with 1991.

Doesn’t looks like Russia will be next Syria…

We’ll be selling sunshine and buying inflation from the US, as if we can live forever on credit.

There is a economic war raging at the moment and the neoliberal finance capital of the collective west is in deep do do!

(Probable) translation: “We will turn the nuclear power stations back on.” I wonder if nuclear power is going to form a big part of Japan’s Green Transformation?

Central bankers don’t know a debit from a credit, a bank from a nonbank, etc. Banks don’t lend deposits. Deposits are the result of lending. All bank-held savings are frozen (e.g., demand deposits shifted into time deposits). I.e., banks are not intermediary financial institutions.

Japan’s “lost decade” is due to the impoundment and ensconcing of monetary savings in their banks. The BOJ has unlimited transaction deposit insurance, the Japanese save more, and keep more of their savings impounded in their banks.

“Japanese households have 52% of their money in currency & deposits, vs 35% for people in the Eurozone and 14% for the US.”

Secular stagnation is just the deregulation of Reg. Q Ceilings. The deceleration in the velocity of circulation. The DIDMCA of March 31st, 1980, presaged as predicted in May 1980, a “pronounced reduction in money velocity”.

files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/83/08/Velocity_Aug_Sep1983.pdf

@ Paulo Rodrigues re: ‘costs in Germany are skyrocketing and many industries will close and transfer production to China + ‘you need skilfull workers if you intend to manufacture cars with Japanese quality standards.’ It’s already happened to a considerable extent. The Chinese city I worked in for several years had a plant making BMW engines. It also had a military-industrial (closed to foreigners) science city and at least one aeronautics expert that I used to play badminton with, who gained his PhD in the UK. I think they have the expertise. Conversely, I remember being surprised to find something simple like a good can opener, made in Germany, in the supermarket. China seems also to be more advanced in moving toward electric vehicles, with provision for charging and share schemes, and gaining the rare earth materials from Africa that it doesn’t sit on. The Republic of China still dominates the semi-conductor industry. A further, though minor, reason I guess for the PRC threatening to restart a bloody civil war ended 73 years ago, in order to regain its Qing Dynasty possessions.

‘Doesn’t looks like Russia will be next Syria…’ They’re not particularly comparable. Russia was meddled in by Western neo-liberals, no doubt, but it’s Russian oligarchs and dictatorial and imperial historical tendency that have taken it where it is. It’s always been reasonably self-sufficient, a conquering, unconquered, imperial power. Syria emerged only in the 20thC from being a subject state. Syria’s war is at heart a civil war, albeit with outside meddling on both sides. There is no civil war in Russia. Russia’s latest war is an attempted imperial land and culture grab. Ukraine is indeed in a tough place, caught between this and western economic imperialism.

@Spencer You got me to look up Regulation Q and the DIDMCA. I must say I can’t think that all the woes from 21stC capitalism can be laid at that American door. On Japan, the documentaryfilm Princes of the Yen still seems to me to offer a good insight.

The DIDMCA laid the legal basis for the addition of 38,000 commercial banks to the 14,000 we already had, and the abolition of 38,000 financial intermediaries (which caused the S&L crisis).

I’m just wondering how the Japanese way would apply to a relatively open economy like the UK’s?

The Government can control interest rates but they can’t control the exchange rate at the same time. MMT explicitly states this should be allowed to freely float. This does mean any Govt would find it difficult to control the inflation rate in an economy like the UK’s which is reliant on the importation of considerable supplies of raw materials, energy and food.

So having a completely freely floating exchange rate isn’t at all politically easy for a country like the UK. If interest rates hadn’t been increased, partially in line with what the Fed was doing in the USA, the pound would have slumped. My guess would be to something like 75 cents. Energy costs would have been even higher and everything else too, which is nearly everything, that depends on energy costs. No government would survive that.

The fault lies with the US Fed. They are creating the conditions for a deep world recession which could be much worse and become a crash followed by a depression.

Dear Peter Martin (at 2022/10/07 at 9:06 pm)

Japan is a very open economy. The yen has depreciated significantly since the Federal Reserve started hiking rates and recently the Bank of Japan started intervening in the foreign exchange market. In the last week, it has significantly reduced its foreign reserve balances.

Your suggestion that only the UK faces these threats to the currency etc is not based in fact.

The difference is that the Japanese government is holding its nerve, whereas it is questionable whether the UK has a government at present.

best wishes

bill

Thanks for your comments, Bill, upon the current UK situation.

We really are in it up to our necks with a hard right Tory shambles of a government and a Labour opposition that gives uselessness a bad name.

The lessons of history have clearly been forgotten, and the result will be a predictable disaster.

What the result will lead to, however, on the political front , waits to be seen.

Thankfully, we have commentators such as your good self to interpret for us.

Keep up the good work!

@ Bill,

Thanks for your reply. I wasn’t implying that currency swings were exclusively a UK problem. However, I’ve just looked up that Japanese exports and imports account for 12.7% and 12.6% of GDP respectively, whereas for the UK the figures are 27% and 28.2 %. So possibly more of a problem for the UK?

You’ll know that currency swings, largely in the opposite direction, have been a problem for Australia too. The high value of the Australian dollar a decade ago just about finished off the Australian car industry and much of what was left of other manufacturing. I know the argument is that this might have been a good thing because it freed up Australian workers to do something more useful, but It would be interesting to test it out with a some studies. It must be very difficult for Australian industrialists to plan ahead knowing that the exchange rate can vary between less than 50 US cents to well over double that.

You’ve indicated that it’s about a country holding its nerve on monetary policy. Would that be possible for a country like Canada, for example, which conducts a large percentage of its trade with the USA? I agree that interest rates should not be used as a primary economic control lever. The fact is, though, that they are. If the world’s dominant economy embarks on an aggressive policy of monetary tightening the pressure is on everyone else to follow suit to defend currency values. So, when crashes inevitably follow, they tend to be international in nature.

So we really need an international treaty to outlaw monetarist economics to prevent the kinds of boom and bust cycles which create economic havoc.

@Patrick B – “There is no civil war in Russia. Russia’s latest war is an attempted imperial land and culture grab. Ukraine is indeed in a tough place, caught between this and western economic imperialism.”

Last I looked, there had been open, bloody civil war between rebel fighters in eastern and southern parts of Ukraine and the central government for the past decade before the Russian invasion. They may not necessarily want to be ruled from Moscow but it could not be clearer that they certainly don’t want to be ruled from Kyiv.

It doesn’t take much of look into Ukraine’s history to reveal that it has long been a deeply and sometimes bitterly divided part of the world for a very long time – very different to the notions promoted in our western propaganda of a harmonious, peaceful and prosperous place that was was struck by an unprovoked invasion like a bolt from the blue. The picture being painted is inconsistent with the facts and the Russian invasion has long been on the cards and was certainly not unexpected. It is largely the result of geopolitical factors much larger than the civil war in Ukraine itself.

I see no logic in stating that Russia’s motivation are simply imperialist aspirations when even the Pope admitted that this is largely about the refusal to guarantee the cessation of the expansion of NATO to the Russian border – Russia’s protests over the past 15 or so years were well documented in our media prior to the invasion but since the invasion, nearly all mention of this basic motivation has been dropped. The facts clearly do not fit the narrative being presented.

Russia has taken what the west has refused to give it – a buffer between it’s homeland border and the massive NATO military alliance. Such motivation is understandable in the context of the fact that NATO was created for the purpose of going to war against Soviet Russia and that this “defensive” alliance has subsequently marched right across the continent from west to east and absorbed almost every part of Europe that does not adjoin the Russian border.

Russia has said countless times that it considers this a direct threat to it’s homeland security. By way of comparison, the Australian government recently cried foul very loudly when it appeared that China would establish a naval base in the Solomons, saying that this was unacceptable because it is Australia’s back yard – it may be but it is thousands of kilometres from the Australian mainland. The US also made it clear in the 1960’s that it was seriously considering using nuclear weapons in response to the Soviet military deployment to Cuba, which is several hundred kilometres from the US mainland with ocean in between.

So if Australia is not prepared to accept a Chinese military presence thousands of kilometres away and the US was not prepared to accept a Soviet military presence hundreds of kilometres away – by what logic would we expect Russia to accept NATO not thousands nor hundreds of kms away but being parked right on it’s border, the north-eastern portion of which is essentially a stones throw from Moscow?

The only “logical” justification I can think of is the notion that we are the “good guys” – therefore, anything we do is justifiable and if we want to roll a huge military alliance right up to Russia’s doorstep, they should simply accept it. Such notions of superior moral justification are at the root of much of the human suffering throughout history.

It seems more sensible to me to consider whether or not we would accept someone with whom our relations were always cool at best expanding their military alliance right to our own front door – because if we don’t, we will likely underestimate just how far they might be prepared to go in order to do what they see as protecting themselves.

Your premise is wrong. You assume that the West is going the path of fiscal tightening. Not the case in the Eurozone, not even in the US. My own country, Lithuania, announced massive subsidies and support measures to businesses and people and will be having a 5% deficit next year. Countries like Germany unveil their fiscal support plans one by one. The main exception is the UK and partly USA (still passed Inflation relief act), which is probably why you get the idea that the entire West is going full austerity mode.

Based on your (@Leftwinghillbillyprospector), I never really look at it like that before (the comparison of apple and apple, so to speak) partly maybe due to our political ideology, geopolitics and the lopsided news we here from media day after day, and the subsequent analyses, right or wrong. Not very neutral now I can see.

Your comparisons of the same act but with different results show hypocrisy at a tall level. It is clearly a double standard treatment. The writing also made me realize that at the end of the day, and whether this issue is really the main cause of conflict, it all came down to our ‘preferences’ in life and living, which might have been determined years ago (or recently, due to what piece of information we hear first and from which side).

Now, I can understand also that this issue is not easily solved. And another thing I can see now is that this situation will drag on and on, based on the history of conflicts we have seen around the world if it is to be any guide (especially ones that is concern with power, autonomy and self determination).

Maybe, piece-keeping forces from the UN is needed, to calm things down and pause the conflicts ‘in time’ for a moment. Maybe, this might bring acceptable solutions for all in time of ‘All in’ mentality.

In my country, this is a vegetarian festival every year for nine days, It brings people to live in a different light completely. Maybe something like this is a good place to start – a pause of something to give ourselves a chance for future path reassessment. (BTW, I don’t want any reply).

@Leftwinghillbillyprospector Me: ‘there is no civil war in Russia.’ You: ‘Last I looked, there had been open, bloody civil war between rebel fighters in eastern and southern parts of Ukraine and the central government for the past decade before the Russian invasion.’ Indeed. Ukraine, not Russia. Where would you and the rebel fighters like the border to be set? Obviously not as set within the Soviet Union in 1927 after much wrangling. Perhaps you feel Kharkov, Ukraine’s second city should be within Russia, since that is what the rebels were after in 2014. My Russian (and Ukrainian) speaking and teaching and Russian culture loving colleague from Kharkov now speaks Ukrainian with her formerly Russian speaking friends, so Putin isn’t converting by his killing and destruction. With regard to Western Propaganda, I’m usually on your critical side, but even the BBC covered the Maidan Protest in 2013 and subsequent conflict. ‘The Russian invasion has long been on the cards and was certainly not unexpected.’ You’re right that it shouldn’t have been unexpected, but it clearly was in some quarters, hence the EU’s increasing reliance on Russian gas. And Putin clearly didn’t anticipate the support that Ukraine would get in opposition to his action to make Ukraine a military occupied puppet state – rather makes a nonsense of the propaganda of the motherland being directly threatened by NATO doesn’t it. As for NATO marching across the continent for the purpose of going to war against Russia – where to begin with that historical illiteracy? Your tale of the Soloman Islands and the Cuban Missile Crisis is a marvellously irrelevant piece of whataboutery, but you could at least try and get the simple facts correct. The distance between Cuba and Florida, recently swum, is just over 100 miles.

This is a worry, if the Economics Director of Deloitte doesn’t get it then Treasury officials, RBA goons and pollies are not likely to either:

“Deloitte Access Economics director Cathryn Lee said the government was likely to make these tough decisions in 2023 or 2024, with its first budget set to be ‘more boring’.

Ms Lee said Australians may need to be prepared to pay higher taxes if they wanted the government to fund existing services and cover emerging priorities including aged care, child care and defence.”

[Bill deleted link to Murdoch press]

Replying to @Peter Martin

You are fearmongering about exchange rate depreciation should the UK go the fiscal policy route of Japan. But you are ignoring the currency is a numeraire.

When a forex rate depreciation hits and pass through inflation occurs due to import prices, the UK government can always CHOOSE to use such events progressively, by raising the wage floor, say with a job guarantee and pension increase. (And civil servant pay rises.). This is trickle up. The rentiers will take their slice of the pie if government lets them, but that too can be avoided by taxing and fining rentiers out of existence.

In other words, an import led inflation can always be used to benefit the lowest wage workers and crush the hoarders and rentiers. It is government policy choice to not adjust prices in this way.

Your fearmongering is justified only because the UK has a neoliberal duopoly who will never compensate forex trends the way Japan does.

@ Bijou,

“the currency is a numeraire”

Is this an MMT based view?

COFFEE, the centre of Full Employment and Equity at Bill’s Newcastle University, describes itself as “seeking to undertake and promote research into the goals of full employment, price stability and achieving an economy that delivers equitable outcomes for all.”

The MMT view is that the Job Guarantee will be used to establish a Labour Standard. The currency is defined relative to the wages of the lowest paid workers in society which would help maintain that price stability. So if the currency is just a “numeraire” then so are workers’ wages. This might be acceptable if we take a purely economic view but I, for one, would have a political problem with this approach – especially in the current situation.

In principle we can all agree that the currency should be allowed to float. But are there limits? In reality there probably are. It would be impossible to maintain price stability in an economy like the UK’s without paying at least some attention to the exchange rate. Many countries have the opposite problem and seek to export capital to keep their exchange rate from rising too high. Another reality is that we don’t have a government which would compensate the less well off in society in anywhere near the way you suggest.