In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Panel of Japanese economists mired in erroneous mainstream constructions and logic

Last Friday, I met a journalist in Tokyo and we discussed among other things, the results of the latest Nikkei/JCER ‘Economics Panel’, which was conducted between November 13 and November 18, 2025. The panel involves “questionnaires” being “sent to approximately 50 economists to gather their evaluations of various economic policies. The aim is to promote deeper and more active discussions on economic policy by clearly conveying the consensus and differences of opinion among experts, along with presenting individual comments from each economist.” The results are quite striking and demonstrate that the Japanese academic economics profession is mired in destructive Groupthink that means the profession is failing to contribute in any effective and functional way to advancing the well-being of the Japanese population or providing insights into how the nation can meet its considerable and immediate challenges.

I discussed this type of process by analysing a University of Chicago survey in 2019 that claimed the results demonstrate how stupid Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is.

Of course, the survey had nothing to do with the body of work we refer to as MMT and so was a dishonest exercise.

The survey respondents were also too insular to realise they were being duped by those conducting the survey – given that none mentioned that the two questions that were under the heading ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ bore no resemblance to any core MMT statements or learnings.

Crippling Groupthink ruled.

See this blog post for more details – Fake surveys and Groupthink in the economics profession (March 19, 2019).

The Nikkei-JCER ‘Economics Panel’ is a little different because the questions were not as obviously rigged and the panel was somewhat more diverse.

But the fact remains that the mainstream dominance was very evident and the mainstream answers were dogmatic whereas the panelists who demurred somewhat were less confident in their reasoning.

You can learn more about the composition of the panel from this page – About Economics Panel (posted August 14, 2025).

The panel is selected by “an appointing committee” who are mostly mainstream academics at Japanese universities.

The questions are of the Agree or Disagree type and “respondents are also asked to indicate their level of confidence in their answers on a five-point scale (1 to 5, with 5 indicating high confidence)”.

There are 50 respondents on the current panel (all Japanese) and drawn from university departments around the world.

In the latest survey, there were 3 questions, one relating to whether the government’s cap on working hours has constrained GDP growth and another relating to whether easing the working hours cap would make workers happier.

So underpinning these questions was a dislike of regulations that were designed to reduce the very long working hours that historically have defined Japanese work places.

The answers were mixed with no clear trend.

1. 40 per cent disagreed with the first question, while 18 per cent agreed. 4 per cent strongly disagreed.

2. For question 2, 42 per cent disagreed (4 per cent strongly so), while 16 per cent agreed.

There was a large ‘uncertain’ group for both questions.

But the question that interested me the most was the third one.

This had been the topic of the Symposium that I spoke at at the Diet Building in Tokyo on November 6, 2025 and which many Members of the Diet (Parliament) and their advisers had attended.

The specific question that was asked of the panel was:

Question 3: Making the primary balance target more flexible from the current single-year basis is appropriate as an approach to economic and fiscal management.

The context was the fact that the new Prime Minister has advocated “responsible proactive fiscal policy”, which means that the:

… approach to the primary balance target has become a point of contention

The Primary Balance is the difference between government spending net of interest payments on outstanding debt and taxation revenue.

The Japanese government had become infested with the mainstream idea that:

As a fiscal soundness goal, the government had aimed for an early achievement of a surplus during fiscal years 2025 and 2026.

Upon assuming her role as the new Prime Minister, she said that the government would interpret this ‘goal’ as a “multi-year” aggregate rather than trying to achieve balance in any single year.

Of course, the government deficit (and primary balance) has been in deficit since 1992 as a result of the government’s response to the massive asset bubble crash in 1991.

The ‘flexibility’ narrative being promoted by Ms Takaichi has sent many economists and commentators into conniptions, and claims of a ‘Truss’ moment have been aired.

At the Symposium, my position was that the actual primary balance should be ignored and attention should be focused on how well the government was progressing to promote social well-being and environmental sustainability – the key MMT construction.

Also note that after the Survey was conducted, the government announced a 21.3 trillion yen stimulus on November 21, 2025.

It is expected that around 50 per cent of that extra net government spending will be covered by tax revenue, given inflation and the booming corporate profits.

Tax revenue is at record highs, which means that the increase in the fiscal deficit will be considerably less than the 21.3 trillion yen.

There are other ‘accounting’ offsets such as dividends coming from government-owned firms and some non-government subsidies that have been refunded through change of circumstance.

They will further decrease the actual increase in the fiscal deficit associated with the 21.3 trillion stimulus.

Note I used the term ‘accounting’ offsets to describe the factors that will reduce the change in the fiscal deficit.

An orthodox economist would claim they were ‘funding’ the spending.

The government will increase its spending by 21.3 trillion by crediting various bank accounts and spending will rise by that much.

The offsets are just book entries, which means in an accounting sense the change in the difference between spending and revenue will be less than the 21.3 trillion yen.

Anyway, back to the question.

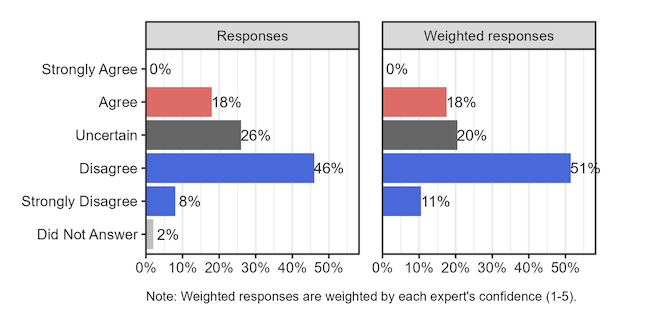

Here are the Responses (and Weighted Response – by confidence level):

So:

When asked whether making the primary balance target more flexible from a single-year basis is appropriate, 54% responded “strongly disagree” or “disagree” (62% after weighting).

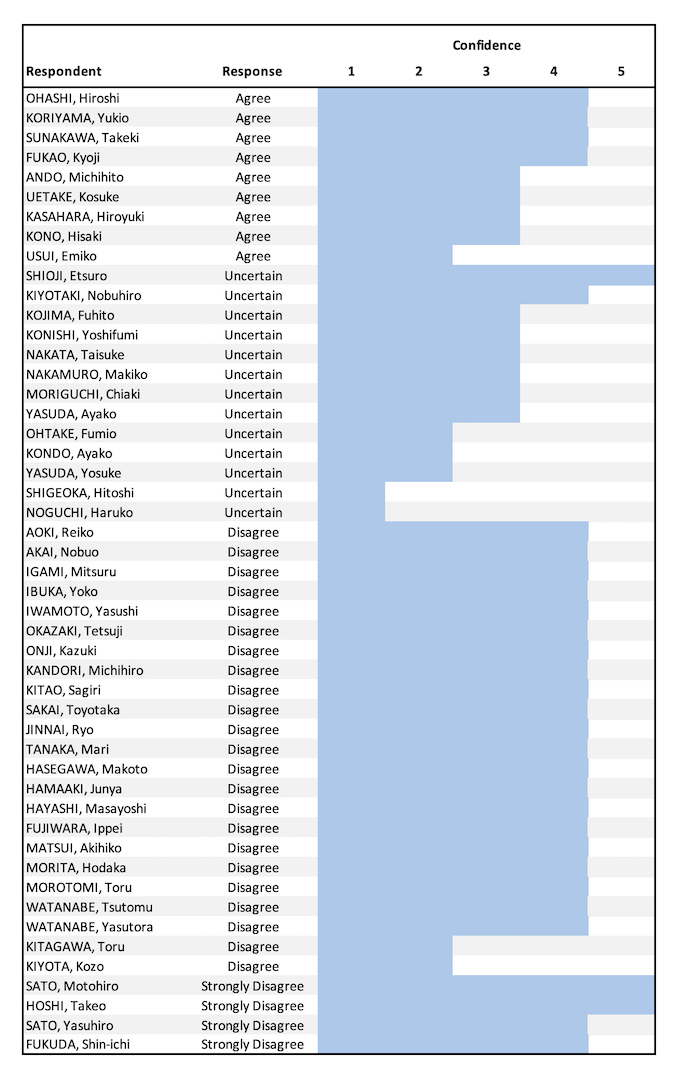

I created the following graphic to show the distribution of the degree of confidence by response.

I think it demonstrates how entrenched the mainstream view among Japanese economists.

The blue bars range from 1 to 5 according to how confident the respondent is in their answer.

Those who agree that flexibility is not going to cause the sky to fall in – a non-mainstream view – are not uniformly super confident in that appraisal.

And there are no respondents who strongly agree.

On the other side – the 62 per cent against (either against or strongly so) are much more confident in their viewpoint.

I note that such confidence has often been displayed when characters like this have predicted the worst as a result of past fiscal deficits etc and have systematically been proven wrong.

Learning from feedback doesn’t appear to be a well established trait among mainstream economists.

That phenomenon is, of course, a key characteristic of Groupthink

The qualitative responses were also interesting.

Several respondents indicated they didn’t “have any expertise” in macroeconomics – which I found interesting – all ‘uncertain’ respondents.

I use the term “conventional logic” to indicate that the person is really applying conventional (mainstream) logic but is not as dogmatic in its application.

I have also summarised several respondents in each category if their comments were similar.

Among the respondents agreeing were statements like (translated from the Japanese):

1. Significant infrastructure, social and environmental challenges require fiscal support – – fairly conventional Keynesian view.

2. Need for fiscal policy to be responsive to economic fluctuations – fairly conventional Keynesian view.

3. Debt ratio falling so no problem – conventional logic.

4. Fiscal expansion needs to consider bottlenecks otherwise inflation will occur.

5. Worry about market credibility and outstanding debt etc – conventional logic.

6. Single-year target too rigid – conventional logic.

Among the respondents who were uncertain:

1. Worried that temporary flexibility will become permanent – “weakening of fiscal discipline”, “loosening of fiscal discipline”, “risks to fiscal management” – conventional logic.

2. Worried about where the spending is being planned.

Among the respondents who disagreed or strongly disagreed:

1. “loosening fiscal discipline”.

2. Increasing deficit is not responsible.

3. Government will not be able to achieve PB surplus over multiple periods.

4. Wants the Prime Minister to resign if a year-to-year PB surplus is not achieved.

5. 30 years of deficits should end.

6. “Fiscal discipline will become more lax”.

7. Flexibility is only appropriate in emergencies (for example, COVID-19) and other times compromises the “long-term debt reduction goals”.

8. Not the time to stimulate with unemployment low (Bill: ignores the fact that there is high underemployment and real wages are falling).

9. Markets will reject the ‘flexibility’ and confidence will be undermined.

10. “Achieving a primary balance surplus every year is not necessarily optimal. However, a mechanism is necessary to prevent unlimited expenditure expansion and maintain fiscal soundness” (Bill: so pursue sub-optimal policy just because!).

11. Fiscal situation is now severe and surpluses are necessary.

12. Will cause interest rates to rise even further (Bill: the erroneous crowding out argument).

13. IMF says the debt ratio is too high and further increases will “jeopardize fiscal sustainability in the future”.

14. In peacetime, a primary balance surplus is required.

My summary is that most of the panel were mired in the mainstream camp.

Even those who support flexibility articulated concerns about on-going fiscal deficits and wanted deficits in the downturn and surpluses in the upturn – the classic deficit dove position.

It was hard to find any respondent who articulated a functional finance position – although one or two depending on the nuance of the translation might have been leaning in that direction.

That is, the vast majority of respondents answered the question within a framework where the logic applied was all about financial ratios rather than thinking about fiscal policy in terms of its function – to do real things like improve well-being, advance socially-productive institutions, deal with climate change, fix up the housing stock to become energy efficient, improve real wages etc.

The panel is stuck in mainstream thinking where deficits are essentially constructed as being ‘bad’ and some respondents were prepared to have some bad for a time as long as the surpluses came later.

That group are characterised as being in the ‘balance over the economic cycle’ camp – where they are prepared to concede some net spending must occur when non-government spending falters, but then the ‘debt’ has to be paid back when the economy is stronger.

That is totally conventional logic.

It completely ignores context and purpose.

Not one respondent expressed a view that ongoing fiscal deficits are required to offset the high saving rates among Japanese households and the low investment rate by corporations.

Certainly, Japan receives a positive income injection from its external sector, which helps ‘fund’ the saving desires of the domestic economy.

But that clearly isn’t sufficient and so fiscal deficits have to fill the remaining spending gap to help ‘fund’ the non-government overall saving desires.

Everytime, the Japanese government attempts to reduce the deficit and push for a primary balance surplus, the economy heads into recession.

That reality means that continuous fiscal deficits are the norm and desirable.

And given the scale of labour underutilisation (currently around 6 per cent, with 2 per cent official unemployment and 4 per cent underemployment) the current deficit is clearly too small.

Hence the need for renewed stimulus.

The other aspect of the comments by the panel members is that single word headlines now serve as a catch all type explanation based on years of conditioning the public to just accept superficial analysis.

So, they can say things like ‘the markets’ and no further analysis is required – the message is the financial markets are all powerful and will sink the yen if the government doesn’t play ball.

The reality is that the exact opposite is the truth.

The markets are mendicants and the government (through the Bank of Japan) can dominate the desires of the markets whenever it chooses.

Even if we accepted the logic that the bond issuance ‘funds’ the government spending, the reality is that the government currently owns more than 50 per cent of all outstanding Japanese Government Bonds and there has been no inflationary consequences as a result.

The inflation that the nation is currently experiencing is coming via food prices and that has been due to adverse climatic conditions during recent harvests – nothing to do with deficits, bond purchases by the central bank etc.

And the government, using the same logic, could buy all the debt if it wanted to and therefore ‘self fund’ itself without any requirements that the private bond investors provide funds.

Of course, that exposes the mainstream logic anyway.

There is a need for more education among the public about these matters – because they are being duped by these well-paid economists who are given a national platform via panels such as the Nikkei/JCER exercise.

Conclusion

The Groupthink exposed by these sorts of exercises is very striking and tells me that we have a long way to go in changing the narrative coming from my profession.

I do not hold out much hope.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“I do not hold out much hope.”

Everyone (at least on the Left) wants government to deliver the essentials for all, which is impossible in a primarily private enterprise, free market system in which governments, following mainstream Neoclassical orthodoxy, confront the ‘Catch-22’ of democratic politics, namely, governments need to *raise taxes* to deliver essential public services, but governments need to *reduce taxes*

to get elected (as Bill Shorten discovered – which is why Labor promised lower taxes than the Coalition in the last election).

Of course *currency-issuing* governments can by-pass this ‘Catch-22’ by eliminating taxes on, and borrowing from the private sector; but managing the risk of inflation other than by central-bank monetary operations, will require an element of *central planning* – verboten in a private- enterprise, ‘invisible hand’ free market system.

Mandating a JG and ZIRP implies replacing the inflation-management role currently residing with the NAIRU-seeking,’independent central bank’, with a Treasury which has complete knowedge of the economy’s productive capacity, and a government which – armed with that knowledge – is committed to delivering the essentials for all, while containing inflation.

In an interview wth Sephanie Kelton, the ABC’s Natasha Mitchell made the observation that ‘big government is ideologically unpopular’; naturally Kelton rejected Mitchell’s contention MMT is “big government”…… yet using the *currency-issuing capacity* of government to bypass the need for taxes on, and borrowing from the private sector, will requires central planning aka big governmemt to avoid inflation, considering external trade is also involved in resource mobilization.

In the context of the curent AI boom, Musk recently said “currencies will become irrelevant and work optional”; central planning will be required to avoid catastrophic social ourcomes as AI eliminates the need to employ everyone, in the quest to improve the quality of life for all on the planet.

The time for ‘big government’ has arrived.