I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

Talk of a Plaza Accord 2.0 should heed the lessons of Plaza Accord 1.0

Pressure is building from the US for a Plaza Accord 2.0 as part of the US President’s attempts to ‘improve’ the US trade situation. I use the term ‘improve’ cautiously because the US President seems think that making it more difficult and expensive for US consumers and businesses to access imports from abroad is a benefit to the same. While Japan is being discussed in this frame, the real US target is China. However, it is unlikely that the US will be able to bully China into agreeing to a similar deal that the US effectively forced on to Japan and other nations under the Plaza Accord 1.0 in 1985. Further, the Plaza Accord 1.0 was extremely disruptive – some say it caused the asset price bubble in Japan, which led to the secular stagnation, after the bubble burst. And, there is little evidence that it led to any significant long-term benefits for the US anyway.

Plaza Accord 1.0

The history of the yen in the post World War 2 era is characterised by a lot of US meddling.

When President Nixon shut the ‘gold window’ in August 1971, which effectively brought the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates that had operated in the period since the end of World War 2 to an end, his motivation was in no small part due to the large current account deficits the US were running against Japan.

The US believed then that the currencies of their main trading partners were undervalued, particularly the yen and the Deutschmark.

Immediately after the US devalued in mid 1971, they negotiated (in December 1971) the Smithsonian Agreement which was an attempt to get several nations to revalue their currencies and re-establish the fixed exchange rate regime abandoned earlier that year.

The agreement wasn’t sustainable given the changes in the underlying trade fundamentals that had brought the system down in the first place and it was abandoned in March 1973.

At that point, most countries floated their currencies, although the Japanese government was under intense domestic pressure to prevent the currency from appreciating because local firms etc did not want a return to the large external deficits of the 1960s.

The Japanese industrialists were mercantilist in their thinking and thought that high-priced imports that the nation was barely able to afford were a good thing.

The upshot was that Japan never really floated in this period.

While the yen did appreciate somewhat during the rest of the 1970s, the two oil shocks really damaged its economy and pushed the yen down so that by the early 1980s, with export surpluses returning, there was a claim, particularly from the US, that the currency was undervalued.

The US has a history of blaming everyone else for their ills, although the trade deficits they were running should have been seen for what they were – a beneficial real terms of trade.

As the Japanese trade surpluses grew, there was clearly strong yen demand in international currency markets but there were offsetting factors which prevented it from rising in value consistent with the growing surpluses.

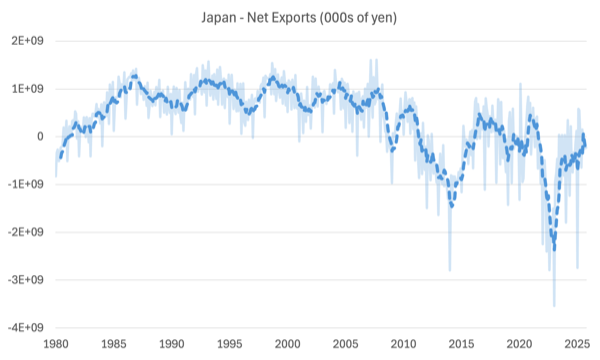

The following graph shows Japan’s net exports against the World (in thousands of yen) since January 1980 (to October 2025) – the Ministry of Finance publishes regular – Trade Statistics of Japan.

The data is monthly and I have faded it and superimposed a 5-month moving average (dotted line) to provide a clearer picture of the trend movements.

You can clearly see the increasing surpluses in the late 1970s and into the 1980s.

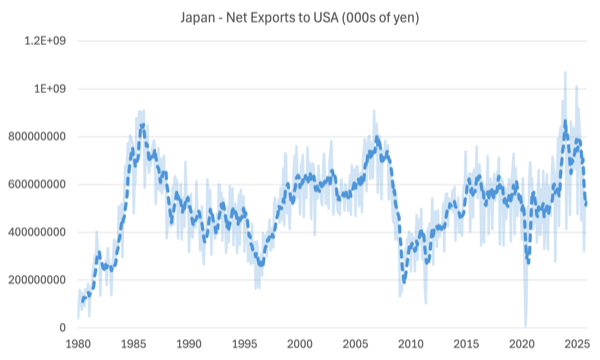

The next graph shows Japan’s net exports to the US over the same period.

Some of these offsetting factors were controlled by the US – for example, the higher US policy interest rates – which were the work of US Federal Reserve boss Paul Volcker at the time.

Ironically, at that time the IMF were trying to assert their neo-liberal stamp on world governments and together with its biggest ‘shareholder’ (the US government) they pushed heavily for deregulation of capital flows between countries.

As the restrictions on international capital mobility were relaxed, the large surpluses Japan had been accumulating courtesy of their trade strength manifested in large outflows on the Capital Account of its Balance of Payments as the Japanese pursued asset building opportunities in other currencies.

These net outflows thus reduced the excess demand for the yen in the foreign-exchange market and that was the main reason the yen didn’t appreciate despite the growing trade surpluses.

But the US government was still obsessed with the notion that the yen (and other currencies) were overvalued and that this was the main reason for their persistent trade deficits.

The mass consumption mentality of the US households was largely ignored in this debate.

Enter the so-called – Plaza Accord – duly named because it was signed at the Plaza Hotel in New York City.

The US was really responsible for the appreciating US dollar at the time.

Volcker’s rate rises and Reagan’s fiscal expansion in 1981-84, created attractive investment opportunities in the US, which led to strong capital inflow, which, in turn, pushed up the US dollar parity.

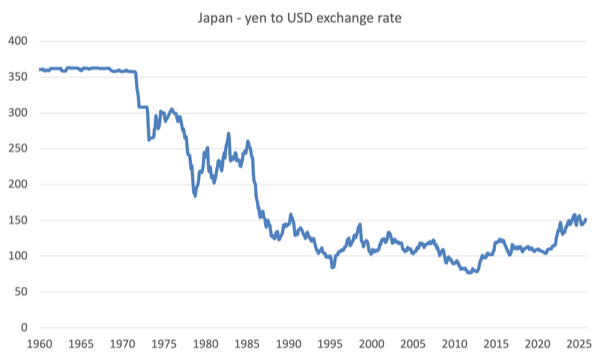

The following graph shows the history of the yen to USD exchange rate from January 1960 to October 2025.

The flat section (360 yen to the dollar) was the Bretton Woods parity imposed by the US occupation forces.

The yen appreciated sharply when the fixed exchange rate system was abandoned.

Between October 1978 and the February 1985, the USD appreciated 41 per cent against the yen (with similar movements against the Deutschmark, Franc and Pound).

By 1985, with the US dollar continuing to appreciate and its trade deficit increasing, the US politicians shifted from opposing any organised currency realignment to actively supporting the notion.

There were a lot of forces pressuring the US government to resist any organised depreciation.

1. The financial markets were profiting from the higher dollar.

2. Reagan considered any lowering of the parity would jeopardise his anti-inflation campaign.

Many large US Manufacturers demanded that they receive protection from what they viewed as adverse exchange rate movements.

Yet, as neoliberalism was now rife, the idea of reintroducing tariffs and import quotas (and other forms of trade protection) was considered to be ideologically unsound.

And the US President responded and cooked up a plan, which materialised as the Plaza Accord.

Meetings in early 1985 between the big five nations (G5) agreed on some managed US depreciation.

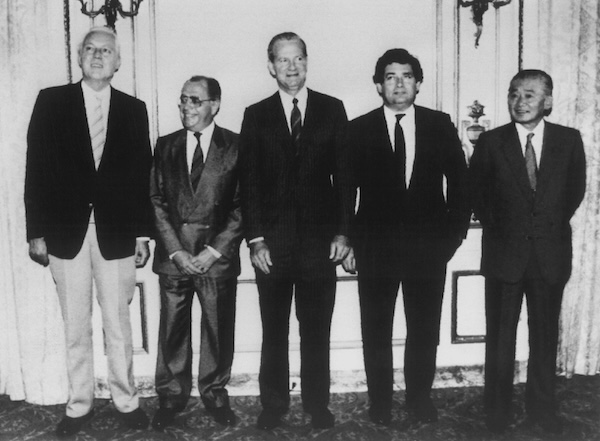

The plans were formalised on September 22, 1985, where senior officials (Ministry of Finance and Central Banks) from France, Japan, West Germany, the US and the UK met and agreed to depreciate the US dollar against the yen and the mark.

The central banks would engage in official intervention in foreign-exchange markets to ensure the currencies moved in the direction outlined in the Accord.

While it was all smiles for the press (from left are Gerhard Stoltenberg of West Germany, Pierre Bérégovoy of France, James A. Baker III of the United States, Nigel Lawson of Britain, and Noboru Takeshita of Japan), the fact is that the US bullied and coerced Japan into signing the Accord.

The Japanese economy was finally beginning to deliver material prosperity to its population after years of struggle following the catastrophe it brought upon itself as a result of its aggression during World War 2.

Officials knew that if they bowed to US demands to appreciate the currency it would effectively bring its growth period to a halt and curtail its export sector.

However, the US insisted and threatened trade litigation and restrictions against the Japanese exporters.

History tells us that the depreciation of the US dollar against the Yen, while it made US manufactured goods cheaper in world markets did not fundamentally alter the trade balance against Japan.

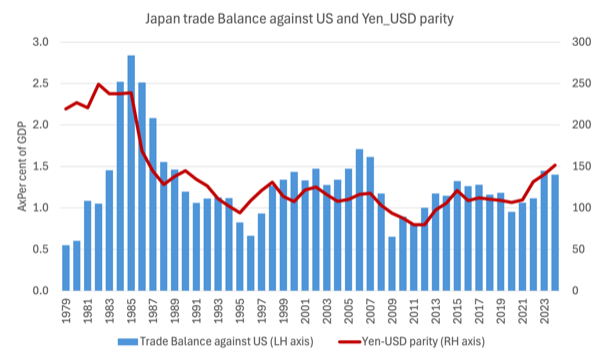

The following graph shows the evolution of the Japanese trade balance (blue bars) with the US from 1979 to 2024 and it Yen/USD parity (red line) over the same period (right-hand axis).

In 1985, the 239 Yen bought $US1 and by 1988 the Yen had appreciated to 128 (a 46 per cent appreciation).

It is clear that the bi-lateral trade balance didn’t react very much at all.

The US Federal Reserve also reduced interest rates to encourage a weakening of the USD.

There are debates about why that result occurred including complaints by the US that Japan imposed import restrictions.

The most salient reason was that the appreciating yen generated the – Endaka – a recession induced by an overvalued yen.

The response from the policy makers to the loss of export competitiveness was to cut interest rates and introduce a large fiscal expansion to offset the loss of exports.

This was a relatively large stimulus and fuelled the asset price bubbles in Japan’s financial and real estate markets through the late 1980s.

The Bank of Japan cut rates by around 3 per cent and held the lower rates through to 1989.

By 1987, the recession was gone and the economy was booming again.

The boom coincided with a period of over-the-top neoliberal relaxation of banking rules which encouraged wild speculation.

However, the massive expansion and freeing up of lending restrictions saw significant credit growth feeding into real estate prices (tripling between 1985 and 1989).

The – Japanese asset price bubble – burst in spectacular fashion in late 1991 (early 1992) following five years in which the real estate and share market boomed beyond belief.

The collapse in 1991-92 marked the beginning of what has been termed the – Lost Decades – which was marked by a trend slowdown in economic growth, deflation, and for the purposes of this post, cuts in real wages as nominal wages stagnated.

Mainstream economists claim that the bubble and the burst were due to excessive domestic stimulation rather than anything to do with the Plaza Accord.

But the fact is that the Plaza Accord deliberately undermined the Japanese economy to benefit the US lobbying interests.

The evidence seems to support the view that it was not the macroeconomic stimulus that caused the asset price bubble but rather it was the financial deregulation in the 1970s and 1980s that was the culprit.

The work of Takeo Hoshi and Anil Kashyap – Japan’s Financial Crisis and Economic Stagnation – (published in 2004 in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 3-26) noted that:

1. The neoliberal financial deregulation allowed larger companies to seek funds from global capital markets.

2. The domestic banks shifted their lending to real estate loans leading to a massive rise in mortgage credit.

3. Further, there was a “conscious policy of Japanese banks to keep extending credit to firms even when the prospects for being repaid are limited.”

Further, the yen appreciation, however, was not enough for the US.

During the 1970s, Japan’s industrial ingenuity saw it become the leader in the production of semiconductors, which it had declared to be a ‘priority industry’.

The – Semiconductor industry in Japan – boomed as a result of cooperative arrangements between industry and the state.

The Japanese government provided significant investment funds to expand the industry.

By the 1980s, Japan produced around 50 per cent of the semiconductors in the world and it became a larger industry than the semiconductor sector in the US.

The US couldn’t hack that.

Japan was growing so fast and leading the world in cutting-edge innovation that the paranoia in the US mounted.

The Japanese were accused of trade dumping – which just reflected the fact that the Japanese manufacturers could produce better products at much cheaper prices because their productivity was higher and their wages lower.

The culmination of these tensions was the 1986 US-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement, which forced Japan, under the threat of trade restrictions from the US, to agree to limit their exports of its semiconductors, increase their prices, and guarantee a specific US market share in the Japanese domestic market.

History tells us that the US chip makers could not cite any evidence that they were unable to sell into the domestic market in Japan.

It is the same argument as for motor vehicles.

The US manufacturers have been unable to produce products that are attractive to Japanese consumers and manufacturers.

There are stories that the Japanese government, to avoid costly and damaging litigation that the US government had threatened against Japanese manufacturers, required those manufacturers to buy US chips – which they did and then just left them in storage because they were not suitable for their purpose.

The US government also slapped 100 per cent tariffs on some Japanese memory chips in 1987, further damaging the Japanese export trade.

It was no wonder that Japan’s share of the global semiconductor market fell dramatically in subsequent years.

The economists who claim that the Bank of Japan should have tightened monetary policy to support the Plaza Accord objectives rarely mention the social instability that an entrenched recession would have created.

The Japanese shifted demand from exports to domestic demand, which was consistent with the demands of the US.

The problem though was that the US manufacturers were not up to the task and their products could gain no significant traction in the Japanese market.

Conclusion

This is on-going work as I analyse the impacts of Trump’s tariffs, particularly on the Japanese motor vehicle industry.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments