I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Is the $US900 billion stimulus in the US likely to overheat the economy – Part 1?

Comments made last week by the former Clinton, Obama and now Biden economist Lawrence Summers contesting whether it was sensible for the US government to provide a $US2,000 once-off, means-tested payments was met with widespread derision and ridicule from progressive commentators. There were Tweets about eviction rates, bankruptcy rates, poverty rates, and more asserting that the widespread social problems in the US clearly meant that Summers was wrong and a monster parading as a progressive voice in the US debate. I didn’t see one response that really addressed the points Summers was making. They were mostly addressing a different point. In fact, the Summers statement makes for an excellent educational case study in how to conduct macroeconomic reasoning and how we need to carefully distinguish macro considerations from distributional considerations, even though the two are inextricably linked, a link that mainstream macroeconomics has long ignored. So while Summers might have been correct on the macro issues (we will see) he certainly wasn’t voicing progressive concern about the distributional issues and should not be part of the in-coming Administration. This is Part 1 of a two-part analysis. In Part 2 we will do some sums. In this part, we will build the conceptual base.

Two levels of analysis involved

Laurence Summers was interviewed by Bloomberg (December 24, 2020) – $2,000 Stimulus Checks Don’t Make Sense, Says Larry Summers.

I wrote about Summers in this blog post – Being shamed and disgraced is not enough (December 18, 2009).

My assessment of him has only deteriorated since.

He will occupy a senior economics position in the incoming US administration.

Pity America.

Here is the – (edited) transcript of the interview from Bloomberg:

… I don’t think the two thousand dollar checks make much sense. The real issue is going to be sustaining this expansion. Think about it. The nine hundred and eight stimulus bill probably would pay out two hundred two hundred and fifty billion dollars a month for the next three months.

The level of compensation is running about 30 billion dollars a month below what we would have expected it would. GDP is running about 70 billion dollars a month below what we would have expected it would. So in a way that’s quite unprecedented. We have stimulus already much more than filling out a hole.

And given that lots of a hole is from the fact not that people don’t want to spend but that they can’t spend because they can’t take a flight and they can’t go to a restaurant.

I don’t necessarily think that the priority should be on promoting consumer spending beyond where we are now. So I’m not even sure that I’m so enthusiastic about the six hundred dollar checks. And I think taking them to two thousand dollars would actually be a pretty serious mistake that would risk a temporary overheat.

I would like to see more assistance to state and local governments. I would like to see more money put into testing more money put into accelerating of vaccines.

But gosh David I think it would be a real mistake to be going to two thousand dollars. And I have to say that when you see the two extremes agreeing you can almost be certain that something crazy is in the air. And so when I see a correlation of Josh and Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump getting in behind that idea I think that’s time to run for cover.

And I know that many of my fellow Keynesians who believe in fiscal stimulus will likely be in favor of this. But sometimes there can be too much too poorly designed of even a basically good idea. And that’s my reaction to two thousand dollar stimulus …

Almost as soon as the interview was made public, progressives went wild.

They pointed out the harm done by COVID to workers and their families, the impending rent eviction maelstrom, the rising mortgage defaults, and all sorts of other social pathologies that are threatening social stability in the US and have been increasing over the last several decades.

The problem is that these responses didn’t really address the issue that Summers was making.

The critics were largely constructing their claims in terms of Summers being a heartless so-and-so who didn’t have a progressive bone in his body and was just reverting to form (of the type I discussed in the blog post linked to above).

I have sympathy with that assessment of the man.

But in doing, the critics failed to contest the actual point he was making – a macroeconomic point.

There were thus two levels of analysis at work:

1. A macro analysis of output gaps (Summers).

2. A distributional assessment of how existing resources and income is distributed in the US (the critics)

Summers might be correct on (1) but sadly lacking on (2).

We need to carefully separate the arguments.

Lawrence Summers was making a macroeconomic point that simply is this.

1. We define potential output where all productive resources are fully employed and no further output can be produced

2. An output gap forms when the current level of spending in the economy drives output below the potential level. This is an indication of how much extra spending is required, taking into account the multiplier effets that follow spending injections, to move the economy back to potential.

3. Driving spending growth beyond that full employment capacity will probably introduce demand-pull inflationary pressures as firms exhaust their capacity to produce and respond to the increasing spending demand by pushing up prices.

So Summers believed that the $US900 stimulus alone would threaten that limit.

Adding another $US1,400 to the cash handout would, in his view, push the economy past the limit.

That assertion is empirically testable (see below) although the frameworks we use to conduct that sort of analysis is ridden with conceptual and measurement problems which means that we are doing art rather than science.

But within the notion of ‘ball park’ estimates, we can make some statements that bear on whether Summers was correct in his analysis.

However, and this is the important point – there is no guarantee that at full capacity, the well-being of the people, the fortunes of the least privileged, the scope and quality of government services, etc – will be at any levels considered desirable.

At the extreme, a nation could be producing all sort of military equipment and all the workers and productive capital fully employed, but with the majority living in abject poverty.

The output gap might be zero – but the society is devastated by poverty and disease.

So within that spending room, there is a debate that to be had about what initiatives are best – so Summers favoured health care and assistance to sub-federal governments rather than a $US2,000 cash handout.

I found that part of his assessment disclosed his own preferences, which progressives might find rather offensive, but doesn’t make him wrong.

So here are some deeper considerations.

The NAIRU redux

The following blog posts cover past writing on the NAIRU:

1. The NAIRU/Output gap scam reprise (February 27, 2019).

2. The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 26, 2019).

3. No coherent evidence of a rising US NAIRU (December 10, 2013).

4. Why we have to learn about the NAIRU (and reject it) (November 19, 2013).

5. Why did unemployment and inflation fall in the 1990s? (October 3, 2013).

6. NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy (November 19, 2010).

7. The dreaded NAIRU is still about! (April 6, 2009).

I also have written books, PhD theses and many Op Eds about this topic.

Here is a summary of the Non-NAIRU facts which taken together provide strong evidence against the dynamics implied by the NAIRU approach:

- Unemployment rates exhibit high degrees of persistence to shocks.

- The dynamics of the unemployment rate exhibit sharp asymmetries over the economic cycle. The unemployment rate rises quickly and sharply when overall spending (demand) contracts but persists and falls slowly when expansion occurs.

- Inflation dynamics do not seem to accord with those specified in the NAIRU hypothesis.

- The constant NAIRU concept (the earliest form of the assertion) was abandoned and replaced by so-called Time-varying-NAIRUs, which became just another ad hoc fudge to try to get the concept to fit the data.

- All NAIRU estimates have large standard errors, which make them all but meaningless for policy analysis. The majority of econometric models developed to estimate the NAIRU are misspecified and deliver very inaccurate estimates of the NAIRU. Most of the research output confidently asserted that the NAIRU had changed over time but very few authors dared to publish the confidence intervals around their point estimates.

- Estimates of steady-state unemployment rates are cyclically-sensitive (hysteretic) and thus the previously eschewed use of fiscal and monetary policy to attenuate the rise in unemployment has no conceptual foundation.

- There is no clear correlation between changes in the inflation rate and the level of unemployment, such that inflation rises and falls at many different unemployment rates without any systematic relationship evident.

- The use of univariate filters (Hodrick-Prescott filters) with no economic content and Kalman Filters with little or no economic content has rendered the NAIRU concept relatively arbitrary. Kalman Filter estimates are extremely sensitive to underlying assumptions about the variance components in the measurement and state equations. Small signal to noise ratio changes can have major impacts on the measurement of the NAIRU. Spline estimation is similarly arbitrary in the choice of knots and the order of the polynomials.

- In the end, the NAIRU estimates are just some smoothed trend of the actual unemployment rate and provide no additional informational content.

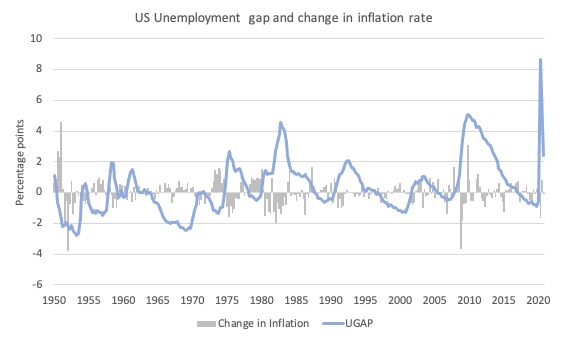

Consider the following graph, which uses data from the March-quarter 1950 to the December-quarter 2020 (the last observation is the average for October and November 2020).

The blue line is the is the gap between the actual unemployment rate (UR) and the CBO estimate of the NAIRU (long-term) while the grey bars are the change in the inflation rate.

We would expect, if the NAIRU framework provided any predictive capacity, that when the gap was positive, that is, the actual unemployment rate is above the NAIRU, that the inflation rate would be falling and vice versa.

There might be some lags in this relationship but we should be able to detect a fairly systematic relationship over time.

There is no such relationship.

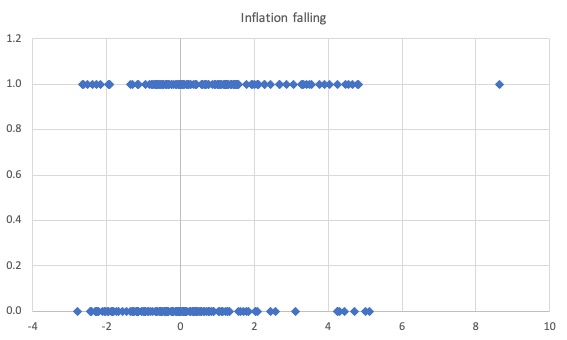

Another way of seeing this more clearly is to consult the next graph which uses the same data but with the horizontal axis depicting the gap between the actual unemployment rate (UR) and the CBO estimate of the NAIRU (long-term) and the vertical axis taking the value of 1 if the inflation rate is falling and zero if it is rising.

We should expect the zeros to be mostly to the right of the zero line on the horizontal axis and the ones to be to the left of the zero line.

The distribution of the observations is nothing like that.

The output gap redux

I started with the NAIRU because it has been widely used to define full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then mainstream economists conclude that the economy is at full capacity.

Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

But they still persist in using it because it carries the ideological weight – the neo-liberal attack on government intervention.

But the point here is that the NAIRU estimates are tied in with estimates of the Output Gap, which is the difference between potential and actual GDP at any point in time.

As I note in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers (November 29, 2009) – the problem is that the estimates of output gaps are extremely sensitive to the methodology employed.

It is clear that the typical methods used to estimate the unobservable Potential GDP reflect ideological conceptions of the macroeconomy, which are problematic when confronted with the empirical reality.

For example, on Page 3 of the US Congressional Budget Office document – Measuring the Effects of the Business Cycle on the Federal Budget – we read:

… different estimates of potential GDP will produce different estimates of the size of the cyclically adjusted deficit or surplus …

The CBO is representative in the way they seek to estimate Potential GDP.

They explain their methodology in this document.

Effectively, the estimated NAIRU is front and centre, so Potential GDP becomes the level of GDP where the unemployment rate equals some estimated NAIRU.

It becomes a self-serving circularity.

Potential GDP is not to be taken as being the output achieved when there is full employment.

Rather, it is the output that would be forthcoming at the unobservable NAIRU. If the estimates of the NAIRU are flawed, then so will the result output gap measures.

The problem is that policy makers make assessments of their current fiscal position based on these artificial, (assumed) cyclically invariant benchmarks.

And, because the estimates of the NAIRU are typically ‘inflated’ (well above what the true full employment unemployment rates are), the conclusion is always that the current discretionary fiscal policy stance is too expansionary (because their methods understate the cyclical component).

Which then means that in recessions, the output gap estimates will be too small, and the extra net government spending that is advocated will subsequently also be too small.

As we saw during the GFC, the more extreme misuse of these under-estimated output gaps provokes the austerity bias – cutting discretionary spending or increasing taxes (mostly the former) when, the reality of the situation is usually indicating the opposite is required.

New Keynesians talk of ‘deficit biases’, when in fact their framework leads to ‘austerity biases’ and elevated levels of mass unemployment and resulting income (production) losses persisting for long periods.

Conclusion

The first problem then is assessing what the output gap actually is.

In Part 2, some arithmetic will be forthcoming.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I must say that Summers’ claim and this analysis are examples of what bugs me about economics and social sciences in general. Making statements like that about poorly understood and certainly not fully quantifiable yet processes is like arguing about what will raise one’s spirits more – 600 butterflies or 2000. Texts like that are hard to follow, much less believe. Many statements about what will raise or lower one parameter or another depending on this or that condition. This is not scientific. Quadratic and linear (with a positive gain) dependencies are both rising. Yet, without a formula one can’t reason about the two, let alone compare. How can one arrive at any conclusion while arguing on the basis of at most rudimentary, certainly not quantitative, estimates in this context? Even worse, our qualitative models are controversial at best in these use cases. All we can say is that giving certain amount of money to people will be beneficial. Giving more than that will likely defeat the purpose. Is it $600? $2000? What is the magic number? I don’t think anyone can say. Making an assertion with such precision is pretending to know more than reality allows.

“What is the magic number? I don’t think anyone can say. ”

You don’t need anyone to say. In fact we don’t want anyone to say What we need is a process by which the number finds its own level automatically and without intervention from anybody.

We have to learn to let the automatic pilot do its job – once we have installed one worthy of the name.

Talking about one off payments tells us that the automatic systems in place are not fit for purpose. Yet few are raising that point.

one way that could give some quantitative estimate is to convert the $600 or $2000 into baskets of real goods for a set of “household types”. One example could be renting families – how much rent/groceries/utilities can it buy? (weeks vs months?)

Another could be to look at a “type” with rent arrears – do these people typically owe $500 or $1500 in unpaid rent? or is it much larger than $2000?

Are many more people in the US hungry because there is no food? Or are they hungry because they don’t have the money to buy food. If it is the first situation then checks aren’t going to help much. But I don’t know anyone who claims that is the case.

Any discussion about this proposal needs to consider the unique political circumstances that exist at this moment in the US Senate but which will be gone within a week. Summers is well aware of the political circumstances and he knows this is not a case where someone can propose and discuss better alternatives and have any chance at all of getting them implemented instead. This is the choice- an additional 1400 dollars to people gets passed right now- or nothing gets passed for months. That is the entirety of the options and he knows that and still he works against it.

Lawrence Summers is clearly angling for a job in the Biden administration. However, as of this date he has not actually received any such position.

Didn’t the great Marx put his finger on the proper way to measure how much money struggling American families should be given to weather the pandemic? From each according to his abilities, to each ACCORDING TO HIS NEEDS. Otherwise, “a nation could be producing all sort of military equipment and all the workers and productive capital fully employed, but with the majority living in abject poverty. The output gap might be zero – but the society is devastated by poverty and disease.” Like the Sabbath in the old saying, the economy was made for man, not man for the economy. Does this not go to the heart of the difference between MMT and mainstream economics?

Re Neil Wilson’s point on automatic stabilisers: excellent point. In my opinion there should also be good background stabilisers as well, e.g. an adequate minimum wage, good unemployment insurance, good public health care, good public childcare, etc. These provide more stability in demand and make people’s circumstances less dire when an economic recession hits. Unfortunately these things are largely lacking in the US for a very large part of the population. I should also point out the achievement of such programs does not require an MMT understanding. Broad political mobilisation is what is needed.

Larry Summers: Bill’s point re Summer’s economic analysis is well taken. The problem is he is so vile it’s hard to get past who he is. In addition to the long list of appalling things he has supported, he is one of the prime architects of the financial deregulation that led to the 2008-9 financial crisis. His webpage at Harvard stated it quite proudly well into the crisis but then it was changed. I know, I had been using it for a speech I was about to give, then poof it was gone! Nonetheless, and as difficult as it is to give him credit for anything, his point about subsidies to the states and municipalities is a very good one.

Larry Summers had an explanatory article about his statements about the $2000 check in the Bloomberg Opinion section. But there are problems with it as well.

Summers calls it a ‘universal tax rebate’ for some reason. That terminology is itself problematic with a proper (MMT) understanding of how the government spending occurs. The US government sending $2000 checks out is in no way a ‘tax rebate’ of any sort- it is pure creation of US Dollars- something the US government does every time it spends on anything in US Dollars. Calling it a universal tax rebate just obscures things.

Summers mostly focuses on household income relative to what he claims is a measure of potential output. His apparent concern is that as household income rises relative to output, then inflation is guaranteed to follow. But that misses the point that total household income is not the same as total household expenditure. Perhaps large increases in total household expenditure would lead to some inflation- but first you have to argue that the rise in income will cause that across the board large increase in household expenditure that might pressure prices. He doesn’t make that case- instead he uses scary numbers coupled with a bunch of assumptions he doesn’t make a great case for.

Here is some loaded language from Larry- ” But further adding to earnings when losses are being replaced seven times over seems hard to justify – especially at a time when pent-up savings totals $1.6 trillion and is rising.” Get it? The savings are ‘pent-up’ AND they are a really big number- just ready to explode dangerously into inflationary excess demand or worse. Surprised he doesn’t claim everyone will go out and buy opioids with the money and overdose themselves and their neighbors.

Summers spends a fair amount of time saying he supports helping people and fiscal policy stimuluses and such excuses to try to make us realize he isn’t some kind of stingy old rich guy- he has a heart! It is just that it is bad economic policy and he can’t responsibly support it even though deep down he would love to help. Or something like that. And there are better more targeted ways to help those who really need it and he would support those instead of this. Unfortunately, this runs into the reality that this is the only deal on the table right now. And the only chance for who knows how long to get anything and the fact it has a slight chance of happening at all is due to some unusual political circumstances that are not going to repeat.

Bottom line- Summers has decided that a chance of some inflation is more important to avoid than the opportunity to provide some help to those who need it right now. That is where he stands.

Well at least Larry Summers does not seem to believe in the ridiculousity that is ‘Ricardian Equivalence’. He’s got that going for him.

Hi Keith Newman. You wrote: ‘there should also be good background stabilisers as well, e.g. an adequate minimum wage, good unemployment insurance… I should also point out the achievement of such programs does not require an MMT understanding. Broad political mobilisation is what is needed.’ But how to ensure an adequate minimum wage and political mobilisation? I’d suggest a MMT Job Guarantee would be a considerable help in achieving an adequate minimum wage in the private sector. And broad political mobilisation needs to be supported by economic education or the myths currently bombarding the public will remain dominant. The Guardian recently quoted an ‘ordinary citizen’ whose first thought was that government acrion would be limited for years to come because of a massive borrowing repayment burden. That chap certainly won’t be mobilised without a little more understanding of the real constraints.

Re: Neil Wilson. You are right. With current level of understanding precise allocation of interventions is not possible. Agree, some degree of policy automation might be helpful. However, in my opinion, the best results can only be achieved with ‘frictionless’ fiscal and monetary tools. What I mean is this. The government should be able to ‘easily’ increase or decrease the effective demand in economy. Currently it can be achieved by fiscal intervention (giving people money, regulating taxation, purchasing goods and services in the market, job creation or destruction etc) or through the central bank (implementing asset buying/selling programs or interest rate manipulation). The former (fiscal tools) is preferable, of course. Impact of the latter is not entirely clear. Still, all these tools, as implemented today, fail to satisfy the requirements of ‘frictionless’ and ‘easy’. Nearly every move faces fierce political resistance primarily driven by the pressure from the industry. It’s not enough to know that the government can spend and tax at will. To take advantage of this knowledge one must implement a real life system where it can actually be done. My previous point was that we simply don’t understand the economy as a system, behavioral patterns, various feedbacks and side effects of our actions well enough to claim that $600 per person is OK, whereas $2000 is going to far (I understand that Summers is doing it for show only, so not using him as a reference). However, given an easy frictionless toolset we don’t have to (as you correctly point out). We can react in real time. That is, of course, if we can also measure the results with some precision. That, too, is required.

It ought to be obvious by now that private market capitalism isn’t 100% reciprocal or commensurable for all which is why Neil Wilson is right to argue for greater use of legislated automatic stabilisers.

Hello Patrick B.

I would argue that three of the four points I mentioned would not require an increase in public spending, an increase in the minimum wage being the most obvious. Also, if unemployment insurance is funded as it is in Canada where workers and employers pay the full amount, then no increase in public spending is required in that case either.

With respect to healthcare I had in mind the U.S. situation since Bill was discussing Larry Summers’ comments re that country. There the cost of healthcare is 6-7 percentage points of GDP more than in other developed countries. Those countries provide care to their entire population while about one third of US-ians have no access to healthcare (according to a study done at Yale). If the US adopted the Canadian or UK system a tax DECREASE would be required to offset the accompanying decrease in demand in the economy. Your fellow concerned by public debt would be reassured! The healthcare situation in the U.S. can best be described as bizarre, even sadistic.

Finally, with respect to childcare, in the province of Quebec where I live there is a system of publicly funded childcare run by parents locally. Parents also contribute to the costs. Both my children went through its precursor 25 years ago and I can attest from personal experience that it is brilliant. It is the fruit of the mobilisation of many women in the province and the presence at the ministerial table of a woman who was intransigent about its immediate implementation. Since the province is not the currency issuer the program must be paid for through higher taxes. Some of the tax increase has been offset by higher labour force participation by women, resulting in higher tax revenue for the province. While neo-liberal ideologues have managed to whittle down the program it still covers one half of all children requiring childcare. If you google “affordable daycare Quebec” you’ll find an article about it and how it has been a model for other countries.

“Lawrence Summers is clearly angling for a job in the Biden administration. However, as of this date he has not actually received any such position.”

And what are the chances that he won’t be, any day now?

I don’t know about you but I’m not holding my breath. I regard that as a more-or-less foregone conclusion.

I hope – fervently, and for America’s sake – that I’m wrong. The man is a public menace IMO. Just look what harm his arrogance and conceit caused to Harvard’s finances; far worse in a wider perspective, at what catastrophic damage not just to the US but the world’s economy his (and Rubin’s and Greenspan’s) unconscionable disparagement and destruction of Brooksley Born’s principled attempt to assert proper regulation of OTC derivatives contributed towards.