I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Commentary on Moody’s downgrade gives the game away – finally

We sometimes encounter commentary that blows away the smoke that provides cover for important myths in the world of economics and finance. Whether that commentary knows the import of its message is questionable but it certainly has the effect of casting aside a myriad of fictions and redefines the sort of questions that one can ask. Such was the case last week following the decision by the ratings agency Moody’s on May 16, 2025 to ‘downgrade’ US government debt ratings from Aaa to Aa1. While many commentators acted in Pavlovian fashion and crafted the ratings downgrade as signifying that the US government was “more likely to default on their sovereign debt”, one influential opinion from the mainstream came out with the conclusion that “there is next to zero chance the government won’t be able to pay its creditors”. Which really game the game away and exposed these ratings agencies as political attack dogs representing sectional interests that want less government money going to welfare and more to them – among other things.

I have discussed the issue of ratings agencies before, for example, among other posts:

1. Ratings agencies and higher interest rates (April 26, 2009).

2. Ratings downgrade on US government debt is as ridiculous as it is meaningless (August 2, 2023).

3. Ratings firm plays the sucker card … again (February 25, 2013).

4. The moronic activity of the rating agencies (October 1, 2012).

5. Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies (December 23, 2009).

We should never forget the role they played in the lead-up to the Global Financial Crisis when they were paid to give Aaa ratings on financial products by the issuers and then lied about it.

The revelations that came out in the US Congress investigations during the GFC on the corruption among these agencies should have seen a conga line of executives marched off to prison and the agencies declared illegal.

Anyway, none of that happened and here we are … again.

In their statement – Moody’s Ratings downgrades United States ratings to Aa1 from Aaa; changes outlook to stable – Moody’s said:

This one-notch downgrade on our 21-notch rating scale reflects the increase over more than a decade in government debt and interest payment ratios to levels that are significantly higher than similarly rated sovereigns.

Successive US administrations and Congress have failed to agree on measures to reverse the trend of large annual fiscal deficits and growing interest costs. We do not believe that material multi-year reductions in mandatory spending and deficits will result from current fiscal proposals under consideration. Over the next decade, we expect larger deficits as entitlement spending rises while government revenue remains broadly flat. In turn, persistent, large fiscal deficits will drive the government’s debt and interest burden higher. The US’ fiscal performance is likely to deteriorate relative to its own past and compared to other highly-rated sovereigns.

In their explanation they said:

1. “Without adjustments to taxation and spending, we expect budget flexibility to remain limited …”

2. “We anticipate that the federal debt burden will rise to about 134% of GDP by 2035, compared to 98% in 2024.”

3. “While we recognize the US’ significant economic and financial strengths, we believe these no longer fully counterbalance the decline in fiscal metrics.”

Which doesn’t really answer the question, does it?

Which is, so what?

Moody’s was just falling into line with the other ratings agencies which had previously downgraded the US government debt rating.

Standard and Poors in August 2011.

Fitch Ratings in August 2023.

Did anyone blink after those decisions were made?

No-one that matters at any rate.

Did the US government fall off the proverbial fiscal cliff?

Not that I noticed.

And so here we are … again.

The commentariat largely interprets the downgrade as somehow reflecting a fiscal crisis.

The various stories cover:

1. The rising interest payments mean that the government can spend less on other things, such as defense spending.

Much has been made of that alleged ‘trade-off’, given that in 2024, the interest payments rose to around 3 per cent of US GDP which exceeded the outlays on defense.

2. It is always claimed that if a government is carrying ‘high’ (whatever high means) levels of debt then it cannot easily pivot and increase spending when some disaster or threat emerges.

3. Governments with high debt become hostage to the flux in sentiment of foreign lenders.

4. And then there are those (many) who claim the ratings signal credit risk – after all they are called ‘Credit Ratings’.

For example, reacting to the decision by Moody’s, CNBC quoted some character in the financial markets as saying borrowing rates will rise because when it is downgraded:

… a country represents a bigger credit risk, the creditors will demand to be compensated with higher interest rates

Even the BBC report – US loses last perfect credit rating amid rising debt (May 17, 2025) – claimed that:

The US has lost its last perfect credit rating, as influential ratings firm Moody’s expressed concern over the government’s ability to pay back its debt …

A lower credit rating means countries are more likely to default on their sovereign debt, and generally face higher borrowing costs.

None of these observations have any particular merit.

On the question of a financial trade-off between say interest payments and, say, defense spending.

Both sources of government outlay add to non-government income.

It is possible that if the US economy was at full capacity and could not absorb increased nominal demand (spending) without triggering a demand-pull inflation that the government would have to make decisions about the size of government relative to the non-government sector and/or about its spending priorities.

In the first case, it could simply introduce policies to increase the size of the government sector relative to the non-government sector – for example, increase taxes.

In the second, the government is always being forced to make choices between spending priorities, not because of financial constraints, but because there are only so many available real productive resources available at any point in time.

Is the US economy at that point in the economic cycle?

The data tells me that there is excess capacity in the US economy and so no spending trade-off is being reached yet.

On the question of less flexibility to meet a crisis – the US government can always meet any crisis that requires increased public spending without question.

It is a pure fiction to suggest otherwise.

In terms of claims that the ratings downgrade indicates increased default risk, which is the sort of headline fiction that is paraded in the media, I read an interesting analysis published in the Japan Times (syndicated from Bloomberg) – Moody’s tells us what we already know about U.S. debt (May 19, 2025) – which really blows away the smokescreen (subscription to Japan Times needed for access).

The sub-heading of the article was:

Take the firm’s decision to strip the country of its top AAA credit rating seriously, not literally

Hmm, what does that mean?

The author, the executive editor of Bloomberg Opinion, wrote:

To be clear, there is next to zero chance the government won’t be able to pay its creditors, and as was demonstrated after the actions by S&P and Fitch, the Treasury Department’s access to funding is determined by forces beyond some letters in a ratings report. Indeed, foreign holders about doubled their holdings of Treasuries since 2011 to more than $9 trillion and have added about $1.5 trillion to their holdings since 2023, according to the Treasury Department …

So although Moody’s action says next to nothing about America’s creditworthiness, it does underscore the country’s increasingly complacent attitude toward rising debt and trillion-dollar budget deficits.

Get the drift?

These ratings agencies are political weapons used by those who want less government spending unless it is for procurement that benefits their own self interest.

They tell us nothing about whether a government is about to default on its liabilities.

As the Bloomberg guy notes – there is next to zero – meaning zero chance of such a default.

So why call them ‘Credit Ratings’?

Because it is a game these neoliberals play to make profits for the ratings agencies and those who speculate in government debt.

The Bloomberg article however struggles to keep its direction and resorts to the fiction:

History provides many cautionary examples of great empires and countries that are no more because of their propensity for fiscal profligacy. And when the money spigots are turned off, the populace revolts.

Well, if I was a US citizen I would be revolting over the way US cities have degraded – like the Kensington district in Philadelphia which belies the claim that the US is a sophisticated world-leading nation.

But exactly how might the ‘spigots’ get turned off?

The US government issues the currency not the financial markets, which means the debt situation, whatever it might be, is irrelevant for assessing the capacity of the government to spend.

And the fact is that the financial markets don’t seem to have got the message that the US is about to default.

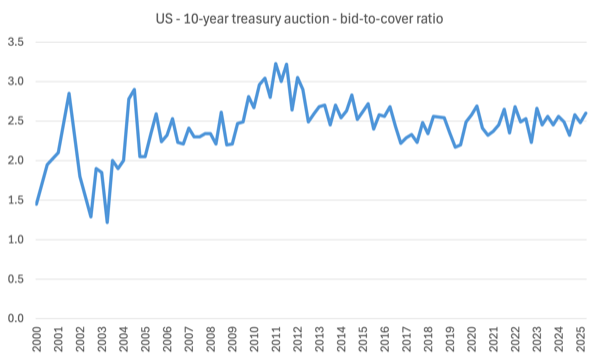

The following graph shows the Bid-to-Cover Ratio for the US 10-year treasury note up to May 15, 2025.

I explained bid-to-cover ratios in this blog post – D for debt bomb; D for drivel (July 13, 2009).

The bid-to-cover ratio is just the $ volume of the bids received to the total $ volumes desired. So if the government wanted to place $20 million of debt and there were bids of $40 million in the markets then the bid-to-cover ratio would be 2.

Over the last 25 years, the bid-to-cover ratio on 10-year treasuries has average 2.4 – signifying no shortage of investors trying to get their hands on the risk-free assets.

First, the use of the ratio assumes it matters. It doesn’t matter at all where the government issues its own currency and is thus not revenue-constrained.

Second, such governments choose the way in which the debt instruments are issued.

The organisation of debt issuance is not dictated by the ‘market’ but a matter of government prerogative.

For example, in Australia, the Federal government changed the way government bond markets operated in the 1980s.

The changes to the ‘operations’ of the bond markets was a voluntary choice by the Government at the time based on a growing acceptance of neoliberal ideology.

They were also the result of special pleading by the private bond dealers who wanted to refine their dose of corporate welfare (the ability to purchase risk-free assets).

There was nothing essential about the changes. Further, they were largely cosmetic.

The Government replaced the former ‘tap system’ of bond sales with an ‘auction model’ to eliminate the alleged possibility of a ‘funding shortfall’.

Previously, governments (such as in Australia) ran what were called ‘tap systems’ of bond issuance.

Accordingly, the government would determine the maturity of the bond (how long the bond would exist for), the coupon rate (the interest return on the bond) and the volume (how many bonds) that was being sought.

If the private bond traders determined that the coupon rate being offered was not attractive relative to other investment opportunities, then they would not purchase the bonds.

The central bank, typically, would then step in and buy up the unwanted issue.

This system, which was very effective and allowed the government to completely control the yield (it set the coupon), was anathema to the neo-liberals, who considered it gave the central bank carte blanche to fund fiscal deficits.

Tap systems were replaced by competitive auction (tender) systems, where the issue is put out for tender and the private bond market determine the final yield of the bonds issued according to demand.

Bonds are issued by government in the so-called ‘primary market’, which is simply the institutional machinery via which the government sells debt to the authorised non-government bond dealers (some banks etc).

In a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates it is clear the government does not have to finance its spending so this institutional machinery is voluntary and reflects the prevailing neo-liberal ideology – which emphasises a fear of fiscal excesses rather than any intrinsic need for funds (of which the currency-issuing government has an infinite capacity).

Once bonds are issued in the ‘primary market’ they are traded in the ‘secondary market’ between interested parties (investors) on the basis of demand and supply.

The bid-to-cover ratio refers to the demand in the primary market by the private dealers for the government debt on offer.

Clearly secondary market trading has no impact on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders.

Under auction systems, the process certainly ensures that that all net government spending is matched $-for-$ by borrowing from the primary bond market dealers.

So net spending appears to be ‘fully funded’ (in the erroneous neo-liberal terminology) by the market.

But in fact, all that was happening was that the Government is coincidentally draining the same amount from reserves as it is adding to the banks each day and swapping cash in reserves for government paper.

Third, it is highly interpretative as to what the bid-to-cover ratio signals.

It certainly signals strength of demand but how strong becomes an emotional/ideological/political matter.

Even if you believed that the government was financing its net spending by borrowing, then a bid-to-cover ratio of one would be fine – enough lenders to cover the issue.

Some commentators think that 2 is a magic line below which disaster is imminent. There is no basis at all for that.

There is also no basis in the statement that a ratio above 3 is successful and by implication a ratio below 3 is unsuccessful.

After all, anything above 1 tells you that some investors do not get their desired portfolio. That sounds like a failure to me.

A declining bid-to-cover ratio might signal that investors are diversifying their portfolios in a growing economy where private asset risk is declining for a time.

Fourth, for sovereign governments the bid-to-cover ratio is somewhat irrelevant because such a government could just abandon the auction system whenever it wanted to if the ratio fell to say, 0.00001.

If the Bid-to-Cover ratios at bond auctions fell to zero – that is, private bond dealers offered no bids for an auction – then the government could simply instruct the central bank to buy the issue.

They might have to change some regulations to allow that but just as nations shifted away from ‘tap systems’ to ‘auction systems’, they can shift back again easily (in most cases).

But as the graph shows, there is a conga line of investors in the primary market keen to get their hands on government debt and they exceed the volume available by some margin – average since 2000 = 2.4.

Conclusion

As they say – ‘nothing to see here’.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

@bill isn’t there logic behind the switch to auctioned bonds? In a small economy like Australia there is a risk of government spending increasing the trade deficit. Floating exchange can, sure, adjust for this, but in doing so it would devalue the AUD and risk an inflationary response. Even if since the accord we don’t think the unions have the power/desire or in more positive terms they are too “disciplined” to respond to price shocks with higher wage demands, this is at least another explanation for why there could be limits on government spending in an open economy, rather there mere neoliberal ideology.

The auction system ensures that the yields rise so that more overseas investors are willing to purchase aus. bonds and thus AUD, so they are providing the funds for a potentially increased trade deficit while preventing any downwards pressure on the AUD.

While the above is in reference to the spread, I’ve heard the same argument regarding why the RBA can’t reduce rates. Apart from inflation, it seems to be another column of the post-80s Australian financial setup that our economy depends on an overvalued dollar. Whether this is true or not I don’t know, but it adds a bit more depth to the motivations for these “reforms”.

@Finn

But isn’t the budget decided by the Legislature? If no one buys the bonds then what happens? The budget isn’t fully spent? What happens if the Government tries spending anyway? Payments aren’t allowed by the Central Bank? Isn’t that a bigger disaster?

@Sid To be clear, government deficits never cause trade deficits. It is growth differentials between two countries – whether this is due to large government expenditure or a solid private investment dynamic – which *may* result in the faster growing country having a larger deficit. The complete opposite is true in the case of the US and China, but this is because China has massive competitive advantages over the US. Given this, the US actually has a very good growth dynamic historically in comparison to e.g the EU precisely because the US gov is willing to deficit spend.

As to your point, I don’t know enough about the mechanics of government budgets. But the Aus. gov can always spend whatever it wants. There is no reason why the tap system allows higher deficits. You can still “monetise” gov. debt under an auction system if the central bank was allowed to purchase government bonds in the secondary market, meaning all desired government borrowing could be met. High interest rates might on the one hand perhaps stabilise the exchange as I mentioned, but the actual disaster would be the choking effect this has on domestic business investment and thus growth. In fact, if what I’m saying has truth at all, it may be empirically that the high interest rates choking business expenditure and thus reducing the trade deficit far outweighs the extra currency reserves obtained from overseas investors as to their respective effects in making the deficit unproblematic.

There is no easy solution here because it all comes back to chaos in a world where there is no cooperation between different countries in regards to exchange regimes and domestic spending. This is really no solution that any one country can implement.

Bill

Thanks for your blogs

Any chance of our thoughts on the “monstrous” (sic) debt of the Victorian government, that will be used to send them to purgatory next state election?