Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

The NAIRU/Output gap scam reprise

It is Wednesday and despite being on the other side of the Planet than usual (in Helsinki at present) I am still not intending to write a detailed blog post today. I am quite busy here – teaching MMT to graduate students and other things. But I wanted to follow up on a few details I didn’t have time to write about yesterday concerning the role that NAIRU estimates play in maintaining the ideological dominance of neoliberalism. And some more details about the Textbook launch in London on Friday, and then some beautiful music, as is my practice (these days) on Wednesdays. As you will see, my ‘short’ blog post didn’t quite turn out that way. Such is the tendency of an inveterate writer.

Macroeconomics Textbook Launch – London, Friday, March 1, 2019

There are a few places left and the list closes 17:00 (Wednesday).

If you want to come, please E-mail me and I will get your name put on the door.

The program for the Book Launch in London of Friday is more or less decided:

- 17:00 Doors open (light refreshments will be served)Doors open (light refreshments will be served)

- 17:20 A welcome from Macmillan International Higher Education & introduction to the launch of Mitchell, Wray & Watts: Macroeconomics 1e – (Philip Rees/Jon Peacock/Jon Finch)

- 17:30 An introduction to the book! – Dr Sandy Hager (City University)

- 17:45 Integrating the MMT approach into the delivery of Macroeconomics HE courses – Professor Heikki Patomaki (Helsinki University)

- 18:00 A word from our author! – Professor Bill Mitchell (University of Newcastle, Australia & Director of CofFEE – (Centre of Full Employment & Equity, University of Newcastle))

- 18:15-18:30 Q&As (compered by Philip Rees, Macmillan)

- 18:45 Finish

Location: The event will be held at the Macmillan publishers complex at the Springer Nature – Stables Building, Trematon Walk, Kings Cross, London from 17:00 to 19:00.

Here is a short video introducing the features of the new textbook

Helsinki Lecture Series

My lecture series at the University of Helsinki in my role as Docent Professor of Global Political Economy, at that university, is underway.

Lecture 1 (Tuesday) attracted a good number including many non-enrolled people from the general public.

The lectures are part of a formal program but the public is welcome to attend subject to lecture hall space being available.

The remaining lecture schedule is:

- Wednesday, February 27 – 12.15-13.45

- Thursday, February 28 – 12.15-13.45

- Tuesday, March 5 – 10.15-11.45

- Wednesday, March 6 – 12.15-13.45

- Thursday March 7 – 12.15-13.45

They will be held in Lecture hall XV (fourth floor) at the University of Helsinki main building, entrance from Unioninkatu.

I have arranged for them to be filmed and when I get access to the footage I will make them available to those who cannot attend.

Output gaps and unemployment gaps – short reprise

In yesterday’s blog post – The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 25, 2019) – we considered in some detail the way in which economists seek to ‘measure’ when an economy is operating at full capacity or full employment. We learned that the measurement process is fraught but not unmanageable. But the real problem is that the process can be hijacked using loaded concepts (such as the NAIRU), which deliberately bias the results of the empirical work towards concluding that fiscal deficits are too expansionary when, in fact, they are too contractionary and vice versa.

At the extreme, we get ridiculous claims from technocratic economists in places such as the European Commission that a nation’s full employment unemployment rate rises from below 10 per cent to 23 per cent in a matter of two or so years due to structural forces that are immutable to government fiscal policy action (such as spending more cash to stimulate sales and create more work).

But even within the limits of the ridiculousness, the bias is profound and nations are forced into imposing fiscal settings that are totally inappropriate for their economies, given the state of non-government spending at the time.

So we see fiscal austerity being imposed when private sales are lagging and unemployment is rising.

And harsh microeconomic policy changes invoked – privatisation, deregulation, wage and income support cuts, etc – which are justified by the claim that the prevailing mass unemployment is purely structural in nature and cannot be dealt with through increasing total spending in the economy.

There was one other graph I constructed to highlight the problems of measurement in this realm of applied economics.

The output gap is conceptually the real output shortfall in an economy relative to its potential (or full capacity) limit.

So in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) parlance it measures the real resource space available in the economy.

It is a conceptual quantity – that is, you cannot observe it.

We observe manifestations of it – mass unemployment, unsold inventories, idle capital etc – which then can help us create proxies in order to measure the unobserved gap.

It is typically derived (estimated) by mainstream economists using another unobserved concept – the NAIRU, which is the unemployment rate where inflation is stable.

The NAIRU was the mainstream replacement for the older notion of full employment.

It was always recognised that some unemployment would always be evident (people moving beteween jobs, for example).

So full employment was logically conceived as there being enough jobs to meet the desires for work from the labour supply.

We can refine that concept to include desired hours of work (to eliminate underemployment).

But the NAIRU recast that conceptualisation and instead redefined full employment to be the unemployment rate where inflation is stable.

Thus, conceptually, the gap between the actual unemployment rate and the estimated (unobserved) NAIRU should measure the non-inflationary space available to reduce actual unemployment.

If that gap – NAIRU minus unemployment rate – is positive then we would expect (according to the theory) inflation to be accelerating.

Conversely, if the gap is negative, then we should expect the opposite.

Various bodies (such as the European Commission, IMF, etc) provide estimates of the NAIRU through a variety of econometric/statistical gymnastics.

The problem is that the estimated gaps between the NAIRU and actual unemployment do not correspond with movements in inflation.

This became very evident early on in the 1990s.

For example, the NAIRU estimates (after the 1991 recession) rose significantly.

Then as the economies around the world recovered and the actual unemployment rates fell, we observed inflation also falling even though the gaps (NAIRU minus actual) were becoming strongly positive.

How could that be?

More gymnastics – bring in the so-called time-varying NAIRU – that is allow it to shift downwards and upwards.

Cutting through all the technical stuff at the time, it was obvious that the estimated NAIRUs were just filtered versions of the actual, which moved in concert with the spending cycle.

In other words, the ‘structural’ benchmark (the NAIRU) was just another representation of the cyclical shifts in employment and unemployment and there was very little if anything structural about it.

I wrote about that in one of my early academic publications where I was the first person to really provide an applied framework for estimating the dependency between the two (hysteresis) – see The NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroeconomic Equilibrium Unemployment Rate (June 1987).

The point is that the two measures of free capacity – the output gap and the unemployment gap – should be closely related if they are to be of any policy use.

If they deviate significantly in estimating how much free resource capacity there is then there is a problem of measurement.

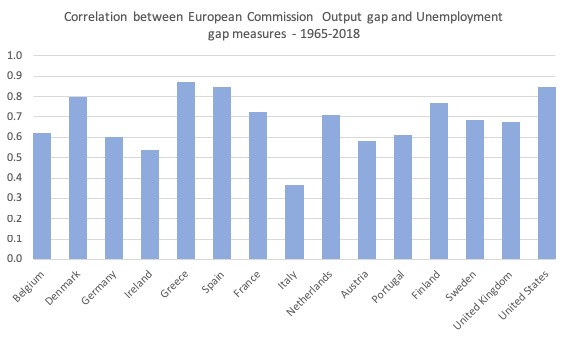

This graph demonstrates that problem.

It is constructed using AMECO data (mentioned in yesterday’s blog post) and shows the correlations for the nation’s concerned of their NAIRU and output gap time series going back to 1985.

The correlations are not particularly strong across the board.

In Italy’s case, the output gap and the NAIRU measures are very divergent, which tells us that one or both are not fit for their stated purpose.

Relatedly, a central bank friend reminded me today of some of the detail surrounding the European Commission’s NAIRU antics in 2013 concerning Spain.

I discussed that in yesterday’s blog post.

In this Working Paper from the German-based Macroeconomic Policy Institute from January 2015 – The European Commission’s New NAIRU: Does it Deliver? – we read that:

1. “The NAIRU is a key component of potential output and as such critically affects output gap estimates” – which is the point I made yesterday. If the NAIRU estimates are cooked, so will the potential output measures be cooked.

2. “Potential output, in turn, is of great relevance for economic policy makers because it represents a barrier to inflation- stable growth and determines the extent to which a given fiscal deficit is interpreted as cyclical or structural” – again what this seemingly technical debate is all about.

Cooked NAIRU -> cooked Potential Output -> cooked Output Gap.

And if the cooked NAIRU is biased to find that the economy is closer to full employment than it actually is, then the cooked output gap measures will suggest the economy is closer to full capacity, which will then mean the current fiscal position will be interpreted as being ‘mostly’ structural.

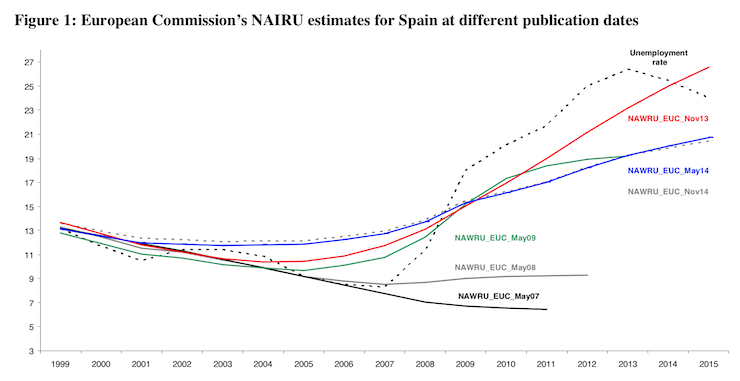

3. “The autumn 2013 forecast of the Spanish NAIRU for 2014 (25 %) almost equaled the unemployment rate in November 2014 (25.8 %). As Spanish unemployment was declining at the time, the unemployment rate was poised to undershoot the NAIRU in 2015 … An unemployment rate of over 20% entailing youth unemployment of more than 50% was thus interpreted labor market tightness.”

And anyone with half a brain immediately concluded as the MPI concluded that this was an “implausible outcome”.

The European Commission came under sustained attack for this ridiculous result and by the European Spring of 2014 they announced they were changing the model specification of NAIRU.

Okay, and then what?

We read that:

Rather than climbing to 26.6% in 2015, the new NAIRU estimate for 2015 was 20.7%.

Remember, that just two years before the NAIRU was estimated to be around 8 per cent.

In the intervening few years, it was implausible to believe that sudden ‘structural’ forces had changed the full employmnet unemployment rate so markedly, especially as Spain was in the midst of a major cyclical downturn.

The European Commission was trying to tell people that there were no cyclical factors at work determining the Spanish unemployment rate.

Absurd.

It is not my intention to review the technical detail in the MPI paper notwithstanding how interesting it is.

Suffice to say, their Figure 1 shows how dodgy this whole exercise is. The different NAIRU estimates keep failing (when considered against the trajectory of the actual unemployment rate) and what the gap between the two would signify for the state of the economy.

So the next time the Commission technocrats crank out the estimates – we see different profiles.

And as the actually unemployment rate rises (around 2007) the NAIRU estimates are also revised upwards, following the actual rate up.

The point the MPI paper makes, which is the point I made in the 1987 paper I cited above is that the unemployment rate trajectory is dominated by cyclical shifts in spending, sales, output and employment.

If the NAIRU basically tracks the actual rate then what independent ‘structural’ information is it providing.

The answer is none, in all probability.

The MPI paper thus tests:

… the dependence of the NAIRU on unemployment versus structural factors …

Leaving aside the technical details of how they did that – essentially they ran regressions of the NAIRU estimates on structural and cyclical variables, to differentiate the two influences – their conclusion is categorical

1. “the NAIRU does not seem to be very responsive to changes” to the structural proxies “as compared to changes in the unemployment rate”.

2. “In general … [the structural shocks] … are largely irrelevant”.

3. “Although interpreted as structural unemployment unaffected by aggregate demand, the EC’s NAIRU turns out to be quite resilient to structural reforms. The estimate is largely driven by actual unemployment.”

Which means that such measures are misleading when applied to policy, and, given the way the bias plays out in the measures – the application is likely to be highly damaging – as we have seen in many countries.

The MPI paper concludes that “output gaps be given less weight in fiscal policy decisions”.

I would conclude that there are much better ways of estimating these things if one abandons the neoliberal mindset that shapes the statistical representations to deliver results that reinforce the dominant ideology.

As the MPI paper notes “the EC does not model the NAIRU to include hysteresis effects”, for a start!

Music for a busy Wednesday

Jet lag means one wakes up in the middle of the night ready for work – notwithstanding the accompanying headaches from lack of sleep. We all know the drill.

So in the quiet, dark hours one seeks comfort from some music to provide the metre for the typing.

This morning, I have been listening to a Dutch pianist, Annelie de Vries, who recently released her debut Post Minimalist CD – After Midnight.

It is a very soothing set of piano pieces, recorded on a very creaky upright piano that she apparently loves to play.

Here is one of the tracks – At Night – it is very lyrical. I think I will work it out and play it myself when I get home to my piano.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Any country at 20-25% unemployment OBVIOUSLY could be producing more real wealth.

However, what do we make of the fact that it is possible to sometimes have high unemployment and high inflation at the same time?

For a modest example:

The U.S. in 1988: 5.3% unemployment, 4.4% inflation.

The U.S. in 1989: 5.4% unemployment, 4.6% inflation.

The U.S. in 1990: 6.3% unemployment, 6.1% inflation.

It would have been very tempting to argue in 1988 that 5.3% was a non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment. But a person would have been wrong in that instance, as inflation did in fact accelerate going into the next year.

Let’s imagine it’s 1988 and you or Stephanie Kelton took a time machine to go back and be the economic adviser to the Democratic Presidential candidate. How would MMT principles be operationalized in a year like 1988? Increase fiscal deficits? After all, 5.3% unemployment is rather high by American historical standards, no? Surely there is more real output that America can produce, no?

Interestingly, even keeping unemployment about the same, inflation began to accelerate upwards. Inflation only came back down after unemployment got up to 6.3% in 1990. And there was no oil embargo in the late 1980s, quite the opposite! So no blaming that issue! Someone who estimated the NAIRU at 5.3% or lower in 1988 would have been empirically wrong.

What I’m getting at is: What if it is possible for Spain’s NAIRU to be 20%, AND for its potential output to be much larger, at the same time? What if inflation turns out to have very little to do with idle capacity in the labor market? Because that’s the way it looks to me. In 2012, Spain had 24.8% unemployment AND 2.4% inflation. If 24.8% unemployment had been very far from Spain’s NAIRU, one would have expected less inflation or even deflation, no? If fiscal policy had driven unemployment in Spain down to, say, 15%, what do you predict would have happened to inflation in Spain?

What asset bubbles were in effect in the mid to late ’90’s? This was the administration of Clinton, and financial deregulation, correct?

If segments of the economy’s productive capacity are idle or there are large numbers of unemployed, then it is very unlikely that these particular areas are driving any inflationary pressures. A job guarantee only targets the unemployed. The additional national government net spending needed to produce full employment may exacerbate some existing inflationary pressures and create some new ones as supply and demand readjust but these should soon dissipate as long as wage hike spirals to match cost of living increases are not permitted. In other words the economy should eventually readjust to the full employment condition with the same previous underlying inflation. The main sources of any excessive inflationary pressure should be determined and some economic levers may be available to alleviate them, regardless of the unemployment level.

I have a simple question: is NAIRU an output result or is it a parameter which is set in order to reach some other result?

Dear Francesco Pellegrini (at 2019/02/27 at 4:54 pm)

The NAIRU is both an OUTPUT (estimated from other data – mostly filtered movements in the actual unemployment rate) and an INPUT into other results, such as the estimates of the output gap.

That is a problem if the initial estimates are imprecise and/or deliberately biased in one direction.

The derivative measures that are then the result of the NAIRU being used as an input are thus tainted.

best wishes

bill

Matthew Opitz. The NAIRU is estimating supposed changes in the rate of change of inflation, and not changes in the inflation rate.

Also, even in theory, to generate a NAIRU outcome you need the aggregate economy to behave with near perfect foresight of inflation. Any inability to forsee the inflationary impacts of changes in the economy tend to make the model no longer generate a stable NAIRU variable, rendering the whole idea gibberish.

So the NAIRU “measures” the “adequate” full-employment rate. Poorly.

If it falls below the current rate of unemployment, the remaining “slack” is attributed to structural “forces” and this is used as a justification for austerity (pro-cyclical) measures. The pro-cyclical measures shrink the economy, jobs are lost but the new estimate of the NAIRU says we are only slightly below full capacity so some more pro-cyclical measures will get us there. Wash, rinse, repeat.

But if it falls above the current rate of unemployment, Bill says:

“If that gap – NAIRU minus unemployment rate – is positive then we would expect (according to the theory) inflation to be accelerating.”

So not only do we not hear a comparable decry of structural issues (would’t it in this opposite case mean inadequate spending?) when the NAIRU consistantly fell below the rate of unemployment (see Spain before 2008) but regard any potential employment gains, e.g. through fiscal stimulus, as inflationary?

Bottom line seems to be that expansive fiscal policy is simply never an option for these guys. This looks like nothing more than a technicalized justification for the “invisible hand” and for the state to do nothing. At all. Ever.

Meanwhile, Japan has more than halfed its unemployment rate in the las 10 years with (a short 4% period set aside) barely noticable inflation (0% < 2%) and sees no reason to rein in its spending or inflict unnecessary unemployment on its population. Still, if one searches for "NAIRU Japan" the top "scientific" result is a 1997 paper titled "The NAIRU in Japan: Measurement and its Implications" by a Fumihira Nishizaki in the OECD iLibrary. It states that:

"[…] These findings lead to the following implications. Structural reform in the labor market should be pursued. Seeking for alternative labor market indicators which move ahead of inflation will be useful. Macroeconomic policy aimed at rapidly reducing unemployment could be costly in terms of inflation."

I think it's safe to say that this prediction did not age well. At least the aauthor bthered to use "could" instead of "would". It boggles the mind that one would not discard such a concept and go back to the drawing board. This is not science.

On another topic, from a Guardian article today:

“Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal proposal, which she launched with the Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts this month, seeks to eliminate greenhouse gas pollution in the United States over the next decade while also addressing inequality with a job guarantee program “to assure a living wage job to every person who wants one”.”

Bill, are you acquainted on the details of this JG-proposal? Without knowing much more than her intention to create a JG-programm around the fight against climate change, I’m ecstatic!

Bill, thanks a lot for your explanation. If I understand well, things can be described as follows:

we observe that unemployment rate is, let’s say here in Italy, 10,5%.

Then we (they…) use a few buzzwords like “structural” and the like to state that such number is “natural” and that we (not them…) must do “reforms” (“structural reforms”, what else?) because we are people not as viruous as them.

Do you think this can be managed and changed by mean of some democratic process?

“Bottom line seems to be that expansive fiscal policy is simply never an option for these guys. This looks like nothing more than a technicalized justification for the “invisible hand” and for the state to do nothing. At all. Ever.”

HermannTheGerman, your comment at 21:46 is spot on.

Herman the German wrote as a quote —

“If that gap – NAIRU minus unemployment rate – is positive then we would expect (according to the theory) inflation to be accelerating.”

Am I crazy? IStM, that in that case inflation should be decelerating.

BTW — this acceerating/decerating mombo-jumbo seems to obscure what is expected.

“If that gap – NAIRU minus unemployment rate – is positive then we would expect (according to the theory) inflation to be accelerating.”

It’s the triple, quadruple, quintuple negatives that get confusing.

NAIRU minus unemployment rate = the number of people who “should be” unemployed minus the number who are.

Being positive means fewer people are unemployed than “should be”.

Meaning more people are employed than “should be”.

Meaning the economy is more active than it “should be” and inflation is looming.

Unless *I*’ve got confused.

Logic will not undo the faith.

The faith is in invisible hands driven by the spiritual force of the price mechanism

Of course deregulation is always the answer

of course government direction of real resources is never the answer

Of course it is a fig leaf for power and wealth

Mel, thanks. I think you are right.