I haven't provided detailed commentary on the US labour market for a while now. To…

The Webbs knew more than a century ago that if you pay high wages you get high productivity

During the recent inflationary episode, the RBA relentlessly pursued the argument that they had to keep hiking interest rates, and then, had to keep them at elevated levels, well beyond any reasonable assessment of the situation, because wage pressures were set to explode. They claimed their business liaison panel was telling them that wages were becoming a problem despite the facts being that nominal wages growth was at record lows and real wages (the purchasing power of the nominal wages) were going backwards at a rate of knots. The RBA massaged that argument by adding that productivity was low and that there was no ‘non-inflationary’ space for wage increases as a result, as if it was the workers’ fault. Yesterday (May 28, 2025), the Productivity Commission (a federal agency that morphed out of the old – Tariff Board – published an interesting research report – Productivity before and after COVID-19 – which lays bare some of the misinformation that the corporate sector has been pumping into the public debate about productivity growth. In particular, it demonstrates that forcing workers to work longer hours undermines productivity growth, that work-from-home is beneficial, and the lack of investment in productive infrastructure by corporations is a major reason for the lagging productivity growth in Australia.

The Economy of High Wages

One of the great contributions to institutional writing in economics, which students in the modern undergraduate programs do not encounter (but should), came from the work of – Sidney Webb – and – Beatrice Webb – who were British socialists.

Sidney was an academic economist and founded the London School of Economics and together they built the Fabian Society into a formidable political fotce advocating progressive policies.

They also founded the New Statesman magazine in 1913 and were instrumental in the cooperative movement in Britain.

They put together an amazing body of work individually and together.

William Beveridge, who motivated the introduction of the modern welfare state in Britain, worked for the Webbs earlier when they published their – Minority Report (Poor Law) – which called for the abandonment of the – Poor Law – and the introduction of a living minimum wage and universal education being provided by the state.

That work significantly influenced William Beveridge’s 1942 – Beveridge Report – which laid out the architecture for the welfare state.

It is amazing how the institutions they created or were members of (such as the British Labour Party) have changed so much from their progressive origins.

In their 1897 book – Industrial Democracy – the Webbs outlined the role that trade unions and collective bargaining can play in a democratic society to improve the fortunes of the majority (workers that is).

The classic section in Chapter IV (Part III) demonstrates the gross imbalance between the power held by workers and the power exerted by employers:

The capitalist is very fond of declaring that labour is a commodity, and the wage contract a bargain of purchase and sale like any other. But he instinctively expects his wage-earners to render him, not only obedience, but also personal deference. If the wage contract is a bargain of purchase and sale like any other, why is the workman expected to tip his hat to his employer, and to say ‘sir’ to him without reciprocity?

These insights were in stark contrast to the mainstream theory (then and now) that held out that the labour market exchange was nothing different to a market for bananas or any other commodity.

In the mainstream narrative there are no power imbalances and trade unions are considered to be market imperfections that should be eliminated to allow the demand and supply forces to work more perfectly.

They devoted their lives to researching the condition of the working class and developing institutional narratives to improve the position of that class.

Importantly, for the purposes of today’s blog post, they wrote in that book that the productivity of workers is a positive function of the wage paid,

Workers were more motivated and healthy in workplaces that paid higher wages.

They argued that even small additions to wages or conditions were beneficial to the enterprise, contrary to the mainstream thinking (p.690):

Hence a comparatively small addition to weekly wages, a more equitable piecework list, a larger degree of consideration in fixing the hours for beginning or quitting work, the intervals for meals and the arrangements for holidays, greater care in providing the little comforts of the factory, or in rendering impossible the petty tyrannies of foremen, — any of these ameliorations of the conditions of labor will suffice, without serious inroads on profits, to attract to a firm the best workers in the town, to gain for it a reputation for justice and benevolence, and to give the employer’s family an abiding sense of satisfaction whenever they enter the works, or cross the thresholds of their operatives’ home

They talked about the advantages of an “economy of high wages” which improves productivity, reduces turnover, and encourages skill development and innovation.

Their work more than a century ago still resonates strongly today and stands in stark contrast to the way mainstream economists and the business community talk about wages – as if they are an impost that should be minimised and the regulations that support wage security should be abolished or watered down.

The Webbs saw that a nation could follow the ‘race to the bottom’ approach where competition is prioritised and unregulated such that cost-cutting is deemed beneficial, labour commodified (that is, dehumanised) and workers are deskilled and forced to work longer hours in the workplace.

You can see those pressures in the modern period.

Even the opposition to the work-from-home trend which Covid-19 precipitated as a matter of survival, is part of that corporate strategy to control workers.

The Webbs thought that approach was not a winning formula for a high productivity society.

Conversely, they advocated a high wage economy where workers are protected with a strong regulative framework and produce high quality products and services using the latest technology.

Instead of bashing down workers to the lowest common denominator, the Webbs wanted employers to invest in best-practice technology and treat their workforces with dignity and pay high wages.

Productivity Commission findings 2025

In the aftermath of the highly restrictive period of the current Covid-19 pandemic, productivity has fallen sharply in Australia.

Business types blame workers for this – too much work-from-home and too much regulation by government.

The business lobby constantly argues for wage suppression, longer working hours, less protections etc.

The normal line without any evidence to support it.

But the Productivity Commission (PC) report cited above rejects these claims.

They find that the drop in productivity in recent years is the result of workers working excessive hours.

They said:

… the pace of growth in hours worked brought with it some downsides to labour productivity (which could have resulted in wages being slow to rise) … the capital stock was simply unable to keep pace with the growth in hours worked …

They also found that the work-from-home trend that has boomed since the pandemic began has not reduced the productivity of workers despite a massive lobby supported by the business sector arguing that without “in-person interactions” productivity slumps.

The Report considers the evidence on “hybrid work” and notes (p.54):

Workers do not need to be in the office full-time to experience the benefits of in-person interactions. As a result, hybrid work (working some days remotely and some days in the office) tends to be beneficial to productivity, or at least, is not detrimental to productivity …

Allowing workers to work from home some days can improve worker satisfaction … and allows people to benefit by avoiding the commute to work, meaning they have additional time for other purposes …

… hybrid work is associated with higher quantity and novelty of output compared to workers who are full time in the office or full time working remotely.

Importantly, the PC argues that “long run investment has been low” or in decline for several decades as a result of corporations not diverting the gains they made from wage suppression into higher investment in best-practice technology.

The low wages growth environment has made it easier for corporations to generate higher profits for shareholders without having to keep pace with innovation.

The PC note that one of the reasons for the low business investment is the “growing market power of firms”:

… as firms can increase revenue by marking-up prices rather than increasing output. Theoretically, firms with more market power may have less incentive to produce output and build capacity, therefore reducing capital accumulation

Hence the low productivity environment.

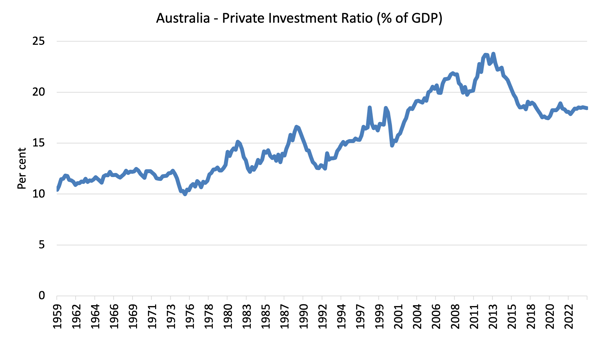

This graph shows the private business investment to GDP ratio (the share of private capital formation expenditure in total expenditure) from 1959 to December 2024.

The decline in the business investment ratio since 2010 is evident and a fundamental reason why productivity growth is slumping.

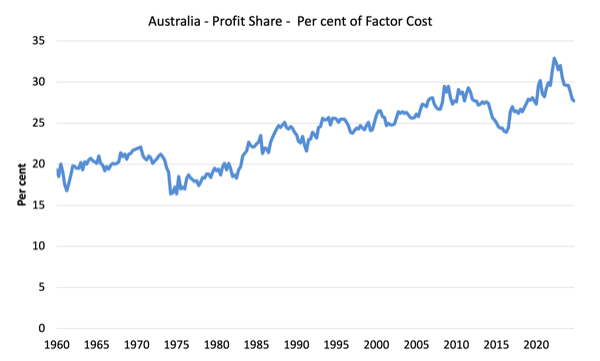

One might be tempted to say that this is because profits have not grown sufficiently.

Which would be false.

Business profits are at record levels and there has been a significant redistribution of national income towards profits at the expense of wages over the last four decades.

This graph shows the profit share of national income for Australia.

Conclusion

Sidney and Beatrice Webb understood all of this more than a century ago but the interests of capital have always railed against their work.

An economy of high wages is the sure path to a highly productivity economy.

There is a plethora of research supporting that position.

The neoliberal period has seen the balance of power tilt back to employers and capital, which has engaged in the antithesis of that approach.

And now the results are pretty clear – record low wages, precarious work, longer working hours, less business investment in best-practice technologies, reduced job stability, and at the end of the causal chain – stagnant productivity.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The 2010-2012 crisis made huge transfers to the tip of the social pyramid. The quantity was so vast, that the wealth didn’t came from the lower classes (that didn’t possess those quantities), but from the very well off. Maybe we can assume that the transfers were mainly from the top 50% of the pyramid to the 1% tip.

And in those 50% you find most, if not all, the decision makers, politicians, justices, managerial class and so on. And so, they had to find a way to recover some of the lost wealth. After all, they are STILL in charge, right?

And then came 10 years of free credit, so they could invest and recover.

But, the west lost its industry and became addicted to gig economics. So, the question arose: where to invest? The answer was: REAL ESTATE!

And so they bought like crazy, in places where that housing could turn a profit, mainly in short-term rents, like local lodging.

By the end of the decade, interest rates hiked like crazy. Credit was no longer free.

Who was to pay that interest? Not the landlords.

And then inflation came along.

How can you expect they can pay their loans, if the diferential between what they pay is not offset by what they get?

Increasing productivity increases overshoot.

The goal is to do less, not to do more with less.

We need land value tax to increase equality.

Claim one: “LVT is a very silly idea because you can’t assign a value to the land without knowing what the value of the denomination you are using is. That ends up being a circular argument.” Set one price JG hour unskilled labour. LVT needs JG.

Claim two: Argument against land value tax “If you try to tax land, then the rich just put the price up, which will then get paid because of the government injections the land tax is trying to fund.” True but land value goes up based on rent as they charge more. In reality LVT is matched with corresponding tax cuts on output and employment, tenants’ net incomes will increase, which will increase rental values and hence rents; so it looks as if landlords are ‘passing on’ the LVT when actually they are just increasing the rent in line with what tenants are willing and able to pay. But even if LVT is a replacement tax, it bring a flood of homes onto the market when people “right-size” (be that up- or down-sizing), which will tend to level rental values downwards.

government injections raise land values, a well-calibrated LVT rises automatically to match, preventing private capture. it is wrong to suggest that it would be an endless upward spiral. All citizens get their share of land value and they can spend it as they please. So it quickly reaches an equilibrium.

Rent is not the only thing a household can spend its money on.

So a household might be prepared to pay £5,000 a year more to have one or two extra rooms or a bigger garden – and in turn they sacrifice having two nice holidays a year, or getting a shiny new car every four years, or working fewer hours.

And some households will be prepared to pay an extra £5,000 to move from a ‘grotty’ area to a nice ‘area’.

But that differential can’t go beyond £5,000 because otherwise more households will say they prefer two holidays a year, or a regular new car, or working fewer hours or whatever.

Something like this: “how exactly tenants would be better off under the LVT system you propose. I get that they’d be no worse off; landlords can’t pass on the LVT, as rents are already set at pretty much the maximum a tenant could afford.

But where do they benefit? They would no longer have to pay council tax, but this just means that the landlord can increase their rent by an equivalent amount. ”

The calculations are all very circular, so it is easiest to start with the end result, which is that the rental value of the lowest value areas will still be £nil, rental values in prime prime areas will be even higher than now, there will be more wealth (less tax on income) and less inequality (tax concentrated land ownership instead of more evenly distributed incomes).

What prevents all growth going into higher rents in the medium or long term is the fact that people’s expectations of a ‘basic minimum’ standard of living (i.e. that which they will spend their money on first before spending anything on land rent) increase nearly as quickly as the economy grows.

(Consider: if every household decided that buying a brand new BMW every few years is one of life’s essentials and put aside £10,000 or towards it, even if that meant that they had to trade down to a smaller or cheaper home, then very few households would end up moving because rents would fall by £10,000 a year!)

John: Increasing productivity increases the output/input ratio. There is a limit to increases in productivity. While increases in productivity are still possible, and they still are possible for some time yet, they can allow us to do the same with less (output ↔ / input ↓) or, since many countries require a degrowth phase, do less with much less again (output ↓ / input ↓↓).

Increasing productivity means an hour of human labour can produce more output; fewer labour hours can produce the same output; and fewer labour hours again can produce less output (if degrowth is required). Productivity rises have been occurring on and off since the advent of agriculture, albeit a lot of the increased production has been the result of increasing the resource throughput over time (output ↑ / input ↑), which does not amount to increases in productivity. At the global level, the throughput has increased to the extent that the global Ecological Footprint is now 1.75 times global Biocapacity, which is clearly unsustainable.

Provided the benefits of increased productivity are equally shared between labour and capital (human-made and natural capital), which in a monetary economy means increasing the real factor payments to labour and capital (which then allow labour and owners of capital to share in the increased financial claims on the increased real stuff produced per unit of real input), workers can enjoy more leisure time (a shorter working week) without having to forgo material standards of living. Or, if degrowth is required, and we all have to accept fewer goods and services, workers could enjoy more leisure time again (and an even shorter working week) as compensation for enjoying fewer goods and services.

The problem at present is that most of the benefits of increased productivity are going to capital. Workers are having to work the same if not more hours to purchase the goods and services required to actively participate in mainstream society (note: I consider the increase in per capita GDP beyond a certain threshold as an increase in the ‘cost to live’, as opposed to an increase in the ‘cost of living’, of which I think the former is what people are really and rightly complaining about).

Thank you for writing about the Webbs. It is great for lay people like me to be introduced to the foundational thinkers in progressive economics.

I know that in my job having a living rather than minimum wage attracts better employees and definitely improves morale. We generally are grateful to get these better wages and we do work hard as a result as there is some loyalty and goodwill to the organization. This creates a better service for clients and means more repeat custom. Precarity in my industry is still a problem though and definitely mitigates against higher productivity as workers stretch themselves too thin across multiple casual employers making them tired, unreliable and forced to drop a shift at short notice if something a bit longer or slightly better paid comes along. This creates a lot of messy uncertainty for employers. I think they would be better off with a smaller pool of reliable permanent workers than large pool of precarious ones.

Thank you for introducing me to the Webbs, Bill. Before this I had to rely upon older sources (like Friedrich List and some rather obscure early 18th century American economists who appear in Michael Hudson’s “America’s Protectionist Takeoff, 1815-1914: The Neglected American School of Political Economy”) when making the argument for the benefits of a “high wage economy.”

I have for years been in ongoing arguments with the neoliberal soaked public discourse in the “Globe and Mail” comments under articles bemoaning Canada’s poor record of productivity increases — which over the last decade have only been appearing with ever greater frequency. Over and over again I have to remind them that tax cuts for Canadian businesses NEVER result in increased productivity enhancing capital investment — the c-suite preferring to engage in real estate speculation and financial engineering, including stock buybacks. Those old enough to remember former (now deceased) Conservative Finance Minister Jim Flaherty’s dismay when he lowered Canadian corporate tax rates to the lowest in North America only to watch his “friends” in the business community pocket the profits, yielding precisely zero increases in either investment or productivity, ought to be wise to the con. Yet still without fail I must endure the endless, tedious repetition of complaints about unions or government spending and debt, or complaints about immigrants and demands for tax cuts and reductions in regulations (invariably dismissed as “red tape”), though lately I have just been seeing some glimmers of hope in the advent of a few other commenters who are beginning to agree with me. Baby steps …

Sidney Webb was the one that persuaded Edwin Cannan to accept a leading position at the LSE.

From Cannan you get the likes of Robbins and Hayek the latter often citing Cannan as being influential in introducing free market liberalism to students.

Beveridge is primarily known because of his work in designing the welfare state. But in some ways his later work ‘Full employment in a free society” is more interesting.

In paragraph 120 of that work Beveridge makes the case for what is effectively a job guarantee.

In paragraphs 283-288 he outlines the internal contradictions in the Keynesian solution to unemployment that will undermine that solution and allow Thatcher to emerge:

“So long as freedom of collective bargaining is maintained, the primary responsibility of preventing a full employment policy from coming to grief in a vicious spiral of wages and prices will rest on those who conduct the bargaining on behalf of labour. The more explicitly that responsibility is stated, the greater can be the confidence that it will be accepted. “ ibid paragraph 288