I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy

Today I have been working with various datasets (labour costs, long-term unemployment) and this blog provides some interesting aspects of what is going on at present. The blog should also be seen in the context of a speech made yesterday by the Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Ric Battellino (a NAIRU devotee) to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia in Perth. His presentation was intending to justify the interest rate hikes that the RBA has been pursuing this year. He continued to assert the RBA line that the Australian economy is running out of spare capacity and so interest rate hikes are necessary. This is in the context of a sharp rise in the exchange rate which is deflationary, actual falls in the inflation rate (and well within their “target band”), more than 12.5 per cent of available labour resources remaining idle and long-term unemployment rising because employment growth can barely keep pace with labour force growth. Macroeconomic policy in Australia is severely distorted at the moment because of the dominance of monetary policy and the obsessions about budget surpluses. In summary, the NAIRU mantra is preventing good macroeconomic policy and the growing pool of long-term unemployed are carrying the burden more than most.

Battellino said by way of summation that:

With the economy now having grown more or less without interruption for about 20 years, it is understandable that spare capacity is limited. This means that the economy cannot grow much above its potential rate without causing a rise in inflation. With a large amount of money continuing to flow into the country over the next couple of years as a result of the resources boom, the challenge will be to manage the economy in a way that keeps economic growth on a sustainable path, with inflation contained. This is what the Bank is trying to do.

That is the official line.

The extraordinary thing about that speech (if you read it) is that he doesn’t make any substantial case to justify the claim that the economy is running out of productive capacity. He mentions the labour market in one sentence where he notes that the appreciating $AUD has damaged the tourism industry in Queensland and “it is not surprising that these areas are currently experiencing among the highest rates of unemployment in the country”.

No other mention.

The same day the ABS released its detailed labour force data which shows that long-term unemployment jumped sharply in the last few months. I will return to that later. But the stunning thing is that Battellino didn’t even mention the labour market in any meaningful way but just chose to perpetuate the story that the economy is near full capacity.

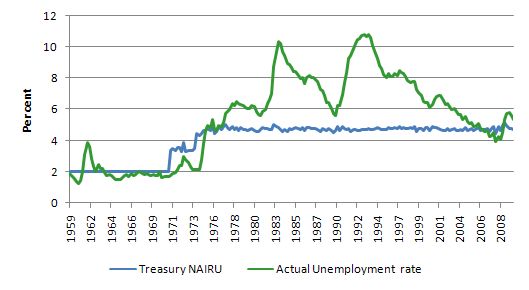

To understand how these ideologues think you only need to consult this graph which shows the Australian Treasury’s estimate of the NAIRU and the actual unemployment rate. You can learn more about the Treasury model via the TRYM Home Page.

An explanatory handbook describes the model. There you will read the following depiction of its “long-run” characteristics:

The model could be described as broadly new Keynesian in its dynamic structure but with an equilibrating long run. Activity is demand determined in the short run but supply determined in the long run … the aggregate supply curve is vertical in the long term at a level of employment and production consistent with the estimated NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment). More precisely, in long run equilibrium the economy grows along a steady state growth path consistent with the NAIRU. There is a wide confidence interval around the NAIRU leading to a degree of uncertainty on the supply side … The model will eventually return to a supply determined equilibrium growth path in the absence of demand or other shocks … The long run is introduced largely for convenience and it may be, for example, that parts of the supply side assumed to be exogenous are partly endogenous (eg the NAIRU and trend labour productivity growth) … In the long run, in the absence of shocks or policy changes, capacity utilisation returns to normal levels and unemployment returns to the NAIRU.

Later in that document they admit that the “level of the NAIRU has significant implications for any short to medium term analysis” (including inflation estimates and interest rate decisions) but that the estimates are unstable and they have no real explanation for the sudden jump in the mid-1970s (read: it was just arbitrarily imposed because the dominant economic theory started to claim that was the reason unemployment jumped in the mid-197s) and that the standard errors around the point estimate are huge.

In fact, there is no meaningful content in the NAIRU time series that the TRYM model uses. It is exogenously imposed on the forecasting process and without any reasonable basis.

Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion about the flaws in the NAIRU. In my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned – we provide a forensic critique of this concept.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) was legally constituted to pursue full employment as one of its three goals (price stability and general welfare being the others). The functions of the RBA Board are set out in Section 10 of the Reserve Bank Act 1959. However, the RBA has been significantly influenced by the NAIRU concept and it conducts monetary policy in Australia to meet an openly published inflation target. The persistently high unemployment in Australia over the last 25 years, would suggest that the RBA is not working within its legal charter.

In September 1996, the Treasurer and Reserve Bank Governor issued the Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, which set out how the RBA was approaching its goals, and articulated that inflation control was its primary policy target (RBA, 1996: 2): The RBA emphasises the complementary role that “disciplined fiscal policy” has to play in an inflation-first strategy. There was no discussion about the links between full employment and price stability except that price stability in some way generated full employment even though the former required disciplined monetary and fiscal policy to achieve it. In a stagflation environment if price spirals reflect cost-push and distributional conflict factors the RBA will always have to control inflation by imposing unemployment.

The RBA answers this apparent contradiction by arguing that the trade-off between inflation and unemployment is not a long-run concern because, following NAIRU logic, it simply doesn’t exist. A high ranking RBA official said in 1999 that:

Ultimately the growth performance of the economy is determined by the economy’s innate productive capacity, and it cannot be permanently stimulated by an expansionary monetary policy stance. Any attempt to do so simply results in rising inflation.

The empirical evidence is clear that the economy has not provided enough jobs since the mid-1970s and the conduct of monetary policy has contributed to the malaise. The RBA has forced the unemployed to engage in an involuntary fight against inflation and the fiscal authorities have further worsened the situation with complementary austerity.

The point of this is that organisations such as the RBA cannot reliably predict inflation (or the real effects of their actions) because according to them the economy is supply-driven in the medium-term and if nominal demand is higher than the “real” growth path then inflation will occur. So if the unemployment rate goes to their estimates of the NAIRU, flawed though they are, these organisations automatically consider the environment is one of accelerating inflation (as a matter of assumption).

The question that arises is: What happens if this growth path is in fact path-dependent (hysteretic)?

Models that impose a NAIRU (natural rate of unemployment) on the economy typically assume this steady-state is invariant to aggregate demand dynamics. It is somehow an aggregate driven by “structural rigidities” etc but when you get down to the supporting papers that the OECD has published in the past (for example, Estimating the structural rate of unemployment for the OECD countries you learn how crooked this concept is.

Thus, while real wages do not adjust in the short-run to “clear” labour markets, eventually, the aggregate demand stimulus generates wage and price inflation as “the gaps between expenditures demand and potential output (GAP) and the actual and underlying structural rates of unemployment (UNR and the NAIRU)” close. The result is that the economy returns to these arbitrarily imposed steady-states.

In Full Employment abandoned – we showed that a lot of the so-called “long-run structural variables” were all driven by the business cycle – that is, aggregate demand. So they were not independent of fiscal policy.

Please read my blogs – Redefining full employment – again! and The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

In my PhD thesis (and an early article published in Australian Economic Papers in December 1987 which was based on my PhD research) I wrote:

Recent policy orientation in the U.K., the U.S.A. and in Australia is based, it seems, on the view that inflation is the basic constraint on expansion (and fuller employment). A popular belief is that fiscal and monetary policy can no longer attain unemployment rates common in the sixties without ever-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. The natural rate of unemployment (NRU) which is the rate of unemployment consistent with stable inflation is considered to have risen over time – labour force compositional changes, government welfare payments, trade-union wage goals among other “structural” influences are implicated in the rising estimates of the inflationary constraint.

In that research, I showed that the increasing NAIRU estimates (based on econometric models) merely reflected the decade or more of high actual unemployment rates and restrictive fiscal and monetary policies, and hence, were not indicative of increasing structural impediments in the labour market? I also showed that there was no credibility in the claims that major increases in unemployment are due to the structural changes like demographic changes or welfare payment distortions.

For the technically minded you might like to read the original article which appeared in Australian Economic Papers, December 1987 which has the formal theoretical model and econometric analysis.

This work was part of a new research agenda that was able to show that structural changes were in fact cyclical in nature – this was called the hysteresis effect. Accordingly, a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

I produced a theoretical model which showed that any structural constraints that emerge during a large recession (more about which later) can be wound back by strong fiscal policy stimulation. I have also produced several empirical articles during that period to verify the claims.

The facts are as follows. Recessions cause unemployment to rise and due to their prolonged nature the short-term joblessness becomes entrenched long-term unemployment. The unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again. But this behaviour has to be seen in the context of the policy position that the national government takes at the time of the recession and the early recovery period. As I show below, this has made a significant difference in Australia.

It is true that once unemployment reaches high levels it takes a long time to eat into it again because labour force growth is on-going and labour productivity picks up in the recovery phase. You need to run GDP growth very strongly at first to absorb the pool of idle labour created during the recession unless you provide a strong public employment capacity that is accessible to the most disadvantaged (for example, this is what the Job Guarantee is about!).

It is also the case that if GDP growth remains deficient then the idle labour queue will remain long and employers will use all sorts of screening devices to shuffle the workers in the queue. They increase hiring standards and engage in petty prejudice. A common screen is called statistical discrimination whereby the firms will conclude, for example, that because on average a particular demographic cohort is unreliable, every person from that group must therefore be unreliable. So gender, age, race and other forms of discrimination are used to shuffle the disadvantaged from the top of the queue.

The long-term unemployed are also considered to be skill-deficient and firms are reluctant to offer training because they have so many workers to choose from.

But to understand what happens during a recession we need to consider the cyclical labour market adjustments that occur.

The hysteresis effect describes the interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

An extensive literature links the concept of structural imbalance to wage and price inflation. It can be shown that a non-inflationary unemployment rate can be defined which is sensitive to the cycle. Given that inflation typically results from incompatible distributional claims on available income by firms and workers, unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital. This is the underlying reason why inflation targetting uses unemployment and a policy tool rather than as a policy target!

Why is all that important? Answer: because the long-run is never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

So these NAIRU-mindsets that just assume that an unemployment rate that touches the “made up” Treasury NAIRU line represents full employment do not provide a reliable guide to policy.

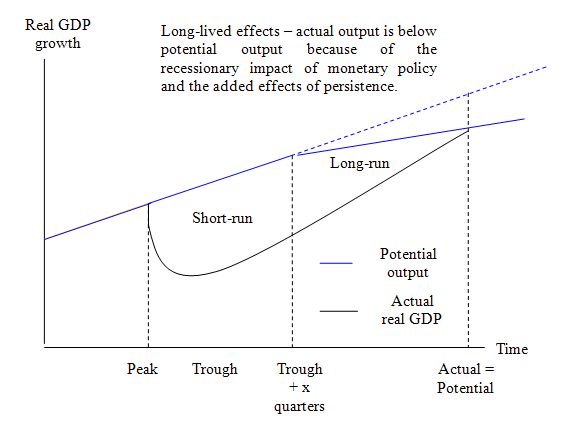

In the blog – The Great Moderation myth I presented the following diagrams which also bear on the point.

Hysteresis theories purport permanent losses of trend output as a consequence of the disinflation. The following diagram shows that the real GDP losses are much greater than you would estimate if you used the neo-classical long-run constraints imposed by the OECD.

You can see that potential output falls after some time (as investment tails off) and actual output deviates from its potential path for much longer. So the estimated costs of the disinflation (and fiscal austerity supporting it) are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit.

But the point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken. Hysteresis means that where you are today is a function of where you were yesterday and the day before that.

By imposing these artificial conservative constraints on their simulations, the OECD is guaranteeing that the main neo-liberal results hold in the long-run.

There is no informational content at all in their outcomes.

Labour cost developments

Now after all that we look at the the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) – Labour Price Index, Australia for September 2010, which was released on Wednesday.

I have known the Melbourne Age economics correspondent Peter Martin for a long time and think of him fondly. He usually writes incisive pieces that tend to provide balance to the more extreme views in the press coming from the mainstream commentators aided and abetted by News Limited.

In his most recent article (November 18, 2010) – Pressure starts to build in the pay cooker – he writes that “AUSTRALIA’S long-awaited wages blowout may be on the way”. This is buying into the mainstream bandwagon that say the economy is overheating and that inflation is about to explode.

It might be Peter but there is not enough evidence here to worry me that a wages explosion is coming from this data release.

To make his case Martin said rather alarmingly that:

After remaining at or below 1 per cent per quarter since the onset of the financial crisis, the Labour Price Index managed 1.1 per cent in the September quarter, with the more closely watched private sector index jumping 1.2 per cent, the biggest increase in the 13-year history of the index.

Which isn’t completely accurate because the seasonally-adjusted private hourly labour cost index grew by 1.2 per cent in the June 2008 quarter as well. Further, the average quarterly growth over the history of the index has been 0.9 per cent with a standard deviation of 0.15 per cent. So the current result is within the 95 per cent confidence interval of “average”.

Martin chose to quote a banking-type economist who said that:

It looks as if wage growth bottomed in December last year … For private sector companies it is not yet excessive, but for workers wages are once again growing faster than prices.

Which means what exactly? Only that the real wage has grown a little. Does that signal any rise in inflationary pressures? Answer: not necessarily. You need to bring in productivity movements and I was surprised Peter Martin didn’t make this important point.

Economists used to talk about the “room” for non-inflationary nominal wages growth. Essentially labour productivity growth provides the room for nominal wages growth to exceed the current inflation rate and not add pressure to inflation.

If nominal wages are W and L is total employment then W.L = the total wage bill facing the economy. Unit labour costs equals the output you get for this wage bill so we might write:

ULC = (W.L)/Y

where Y is total real output. We could calculate this on an hourly basis or whatever.

Note that this can also be written W*(L/Y) and (L/Y) is the inverse of labour productivity (output per unit of labour input). So W/(Y/L) is also unit labour costs.

This means that if nominal wages grow in line with labour productivity growth then ULC will be constant. However, what happens in real terms is what matters.

A related concept is the wage share which is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP.

To compute the wage share we need to consider total labour costs in production and the flow of production ($GDP) each period.

Employment (L) is a stock and is measured in persons (averaged over some period like a month or a quarter or a year.

The wage bill is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (W) prevailing at any point in time. Stock (L) become a flow if it is multiplied by a flow variable (W). So the wage bill is the total labour costs in production per period.

So the wage bill = W.L as before. The wage share is just the total labour costs expressed as a proportion of $GDP – (W.L)/$GDP in nominal terms, usually expressed as a percentage. We can actually break this down further.

Labour productivity (LP) is the units of real GDP (Y) per person employed per period. Using the symbols already defined this can be written as:

LP = Y/L

which is what we found above. This tells us what real output (GDP) each labour unit that is added to production produces on average.

We can also define another term that is regularly used in the media – the real wage – which is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period. To compute the real wage we need to consider two variables: (a) the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P).

We might consider the aggregate price level to be measured by the consumer price index (CPI) although there are huge debates about that. But in a sense, this macroeconomic price level doesn’t exist but represents some abstract measure of the general movement in all prices in the economy.

Now the nominal wage (W) – that is paid by employers to workers is determined in the labour market – by the contract of employment between the worker and the employer. The price level (P) is determined in the goods market – by the interaction of total supply of output and aggregate demand for that output although there are complex models of firm price setting that use cost-plus mark-up formulas with demand just determining volume sold.

The inflation rate is just the continuous growth in the price level (P). A once-off adjustment in the price level is not considered by economists to constitute inflation.

So the real wage (w) tells us what volume of real goods and services the nominal wage (W) will be able to command and is obviously influenced by the level of W and the price level. For a given W, the lower is P the greater the purchasing power of the nominal wage and so the higher is the real wage (w).

We write the real wage (w) as W/P. So if W = 10 and P = 1, then the real wage (w) = 10 meaning that the current wage will buy 10 units of real output. If P rose to 2 then w = 5, meaning the real wage was now cut by one-half.

Nominal GDP ($GDP) can be written as P.Y where the P values the real physical output (Y).

Now if you put of these concepts together you get an interesting framework. To help you follow the logic here are the terms developed and be careful not to confuse $GDP (nominal) with Y (real):

- Wage share = (W.L)/$GDP

- Nominal GDP: $GDP = P.Y

- Labour productivity: LP = Y/L

- Real wage: w = W/P

By substituting the expression for Nominal GDP into the wage share measure we get:

Wage share = (W.L)/P.Y

In this area of economics, we often look for alternative way to write this expression – it maintains the equivalence (that is, obeys all the rules of algebra) but presents the expression (in this case the wage share) in a different “view”.

So we can write as an equivalent:

Wage share = (W/P).(L/Y)

Now if you note that (L/Y) is the inverse (reciprocal) of the labour productivity term (Y/L). We can use another rule of algebra (reversing the invert and multiply rule) to rewrite this expression again in a more interpretable fashion.

So an equivalent but more convenient measure of the wage share is:

Wage share = (W/P)/(Y/L)

which says that the real wage (W/P) divided by labour productivity (Y/L).

I won’t show this but I could also express this in growth terms such that if the growth in the real wage equals labour productivity growth the wage share is constant. The algebra is simple but we have done enough of that already.

That journey might have seemed difficult to non-economists (or those not well-versed in algebra) but it produces a very easy to understand formula for the wage share.

Two other points to note. The wage share is also equivalent to the real unit labour cost (RULC) measures that Treasuries and central banks use to describe trends in costs within the economy. Please read my blog – Saturday Quiz – May 15, 2010 – answers and discussion – for more discussion on this point.

The point of all this is that if RULCs are not rising then there are no inflationary pressures emerging from the labour market. In other words, the growth in productivity provides the “room” for the the growth in real wages (nominal wages growth in excess of the current inflation rate).

That should always be the focus – has there been “room” for this nominal wage increase.

To help us I did some analysis using the ABS data. This is the graph that commentators this week have dubbed a wage explosion. It is taken from the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) – Labour Price Index, Australia for September 2010. The graph shows the annual growth in hourly nominal pay for the economy as a whole (blue line), the public sector (red line) and the private sector (green line) from September 1998 to September 2010.

You can see the recent recession dampened private sector hourly wages growth considerably and as the economy has resumed reasonable growth patterns the wages growth is getting back on track. The stimulus impact of the public sector is obvious with a boost to public wages from 2008 to sometime in 2009 and that is now waning.

On the surface of it, this is not a worrying nominal trend.

But was there room for this nominal wages growth? Answer: Yes, read on.

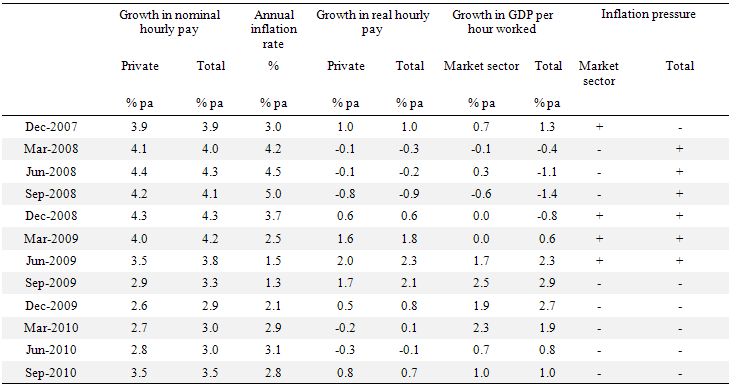

The following Table tells us the story since December 2007. The second and third columns are the annual growth in nominal hourly pay since December 2007 for the private (market) sector and the economy in total, respectively. The next column is the annual inflation rate which gives the real equivalents for the market sector and total economy in the next two columns. The next two columns show the annual growth in market-sector and economy-wide productivity (taken from the national accounts and estimated conservatively for the September quarter given that data is not yet available).

The final two columns show whether the real wages growth exceeds (+) or is less than (-) the growth in productivity for the respective sectors (market and total). If the sign is negative then the nominal wages growth has not resulted in any “inflationary pressures” and vice versa. There are a lot of negative signs over the last year!

I would also qualify this analysis by saying that underlying the + or – interpretation is an assumption that the current wage share is the true equilibrium. I don’t actually believe that and in fact would argue that to restore stability into the next growth the wage share will have to rise quite significantly. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

But even with that highly restrictive assumption (that the current wage share is appropriate) the growth in hourly pay is not adding any inflationary pressures at present.

I could further disaggregate this into components of the market sector but the message will be pretty similar.

The other point to note is that productivity growth is low at present and will gather pace in the coming quarters. This will further depress the impact of any nominal wage rises. So while there was a rise in nominal hourly pay in the last quarter there is every reason to believe this is within the “room” provided for by labour productivity growth. That is – no cause for alarm.

Meanwhile … long-term unemployment is on the rise

The last point to note is that on the day the RBA was telling us that there is very little spare capacity available in the Australian economy (Thursday) the ABS released their Labour Force, Australia, Detailed – Electronic Delivery data for October 2010, which gives up-to-date estimates of long-term unemployment.

In this blog – Long-term unemployment – stats and myths – I show that there is no supply constraint binding as a result of long-term unemployment. If employment growth is strong enough then both unemployment pools – short-term and long-term are drawn down by employers.

As unemployment started rising in the 1970s and has persisted at high levels ever since, orthodox economists concentrated on the supply side of the labour market, hypothesising that full employment should be redefined to occur at much higher unemployment rates than in the past. Remember my definition of full employment is less than 2 per cent official unemployment, zero hidden unemployment and zero underemployment.

However, Michael Piore (1979: 10) reminder is worth remembering always:

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original)

(Reference: Piore, Michael J. (ed.) (1979) Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc.: White Plains.)

The orthodox approach, however, has been to consider long-term unemployment to be a (linear) constraint on a person’s chances of getting a job. The so-called negative duration effects are meant to play out through loss of search effectiveness or demand side stigmatisation of the long-term unemployed. That is, they become lazy and stop trying to find work and employers know that and decline to hire them. Over this period, skill atrophy is also claimed to occur.

So it has been common for mainstream economists and policy makers to postulate that there is a formal link between unemployment persistence, on one hand and so-called “negative dependence duration” and long-term unemployment, on the other hand. Although negative dependence duration (which suggests that the long-term unemployed exhibit a lower re-employment probability than short-term jobless) is frequently asserted as an explanation for persistently high levels of unemployment, no formal link that is credible has ever been established.

However, despite the lack of evidence, the entire logic of the 1994 OECD Jobs Study which marked the beginning of the so-called supply-side agenda defined by active labour market programs was based on this idea.

This agenda has seen the privatisation of the Commonwealth Employment Service, the obsession with training programs divorced from a paid-work context and the raft of pernicious welfare-to-work regulations. All have largely failed to achieve their aims.

Once you examine the dynamics of the data you quickly realise that short-term unemployment rates do not behave differently to long-term unemployment rates. The irreversibility hypothesis is unfounded.

The following graph shows the Long-term unemployment ratio (% of total unemployment) and the unemployment rate (%) from September 1997 to October 2010. The relationship between long-term unemployment and the unemployment rate is very close. As unemployment rises (falls), the PLTU rises (falls) with a lag.

Several studies have formally examined this relationship and all have found that a rising proportion of long-term unemployed (PLTU) is not a separate problem from that of the general rise in unemployment. This casts doubt on the supply-side policy emphasis that OECD governments have adopted over the last two decades. So while the OECD and its mainstream lackeys all claim search effectiveness declines and this contributes to rising unemployment rates, it is highly probable that both movements are caused by insufficient demand. The policy response then is entirely different.

The reason that long-term unemployment is rising sharply again in Australia is because employment growth is not strong enough. In recent months employment growth has barely kept pace with labour force growth (and last month failed to). In that sort of environment, the unemployment sequence through increasingly longer duration categories and more spill over into the 52 weeks or more (which is the definition of long-term unemployment in Australia).

So it amazes me that the Government and its central bank (RBA) are willing to just disregard the growing number of unemployed and treat then as part of the NAIRU. At present there are 646 thousand unemployed and the implied Treasury TRYM model full employment unemployment level (NAIRU) is 574 thousand.

But it gets worse. Underemployment currently stands at around 7.5 per cent or 874 thousand workers who want on average around 14-15 extra hours per week but the demand ration on the labour market (that is, inadequate growth rate) prevents them from working harder. Just a rough rule of thumb suggests that the underemployment translates into about 400 thousand full-time equivalents of spare capacity.

So more than a million workers (in full-time terms) are available and the RBA claims we are close to exhausting capacity.

If the problem is sectoral – then fiscal policy is the appropriate tool to use. The current reliance on increasing interest rates to “temper” the alleged inflation threat is damaging the weaker parts of the economy. In fact, only really mining is booming at present. It would be far better to restrict resource demand in that sector with an appropriately scaled Resource Rent Tax and inject net public spending in the regional areas in the non-mining states to ensure that this long-term unemployment is mopped up quickly.

At present the policy balance – rising interest rates and contractionary fiscal policy – is completely the opposite to what Australia needs to achieve the goals of full employment and price stability.

Meanwhile …

Our budget-surplus obsessed national government – self-styled champions of women’s’ pay equity – have refused to support a pay adjustment for women as part of an equal pay test case currently under-way in the wage tribunal.

This time last year the then Employment Minister (now Prime Minister) agreed to support the pay rise to create “an appropriate equal remuneration principle”.

But now the Federal Government has presented is submission to the hearing which includes:

The government’s fiscal strategy – which is aimed at ensuring fiscal sustainability and returning the budget to surplus – will influence the government’s ability to support the sector in meeting additional wage costs … If any additional government funding is provided, it would likely come at the expense of other government-funded services.

So this is just another example of how appropriate social policy development is subjugated to the neo-liberal straitjacket of fiscal austerity. The latter has no substance or basis.

It demonstrates what has happened to the “progressive side” of politics. As the neo-liberal ideology gained dominance the progressive parties (including the current government’s party) started to move further and further to the right. They still mouth off slogans about being committed to “removing historical barriers to pay equity” but then block all social policy development that might achieve that in the name of the amorphous budget surplus ambition.

Truly mindless.

Digression: good on us!

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the first issue of its Environmental Issues: Water use and Conservation, Mar 2010 data today which indicated that:

The prevalence of rainwater tanks as a source of water for Australian households continues to increase. Twenty six per cent of households used a rainwater tank as a source of water in 2010 compared with 19% of households in 2007 and 17% in 2004. South Australia continues to have the highest proportion of households with a rainwater tank (49%) but there was a marked increase in the proportion of households with a rainwater tank in Queensland and Victoria. Households that use a rainwater tank as a source of water in Queensland increased from 22% in 2007 to 36% in 2010. Similarly, rainwater tank use in Victoria increased from 17% in 2007 to 30% in 2010.

We have two tanks at our place! And according to the saying – “when you have too many rain water tanks you barely have enough!”

Conclusion

Europe is waking up soon and the live coverage of the crisis will start for another day. Checking the scoreboard overnight tells me that Ireland has been invaded by parachuting hostiles; the Irish government should sack the central bank governor there moments before resigning themselves; and denial abounds. Anyway, we will see what happens today (tonight!).

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even curlier than last week!

That is enough for today!

I have a question about QE. I read somewhere that the new reserves created by the FED can be withdrawn by banks and converted into cash, is this possible?

sorry, my post is not related to this particular blog entry. Perhaps somebody can explain this to me:

if bank lends 1 million – then it creates 1 million deposit (which borrower spends) and 1 million liability, as I understand. However, with interest the borrower must return 2 million. So:

How can it be said that this horizontal transaction amounts to net 0 sum? Borrower has to find the 2 million somewhere (of course only over time), while only 1 million was spent into economy.

Is the assumption here – that over the time that 1 million spent into economy will become 2 million? But how? Only through lending it to somebody who will owe interest as well. So expectation is that government will spend these amounts into economy over that time?

In any case it does not seem like zero sum horizontal transaction to me.

Thank you.

I have never really understood people who call them self liberals and think they have the right to condemn large parts of the general public to unemployment in the name of an economic dogma like NAIRU. No matter how valid as economic theory I can’t see that anyone who claims to be a liberal can give them self this right to put their fellow citizens in misery.

We usually don’t believe it’s our right to e.g. eradicate people that is not productive because it’s economically sound, but “we” obviously think it’s right to condemn a certain percent of the people to unemployment and misery because a unproved economic dogma say it will prevent inflation.

This summer the potential social democratic finance minister in Sweden was very disturbed that the economic high priests in official institutions have raised the NAIRU above 6 percent (of course NAIRU is nothing that make the headlines or generally debated), or as they like to call it here equilibrium unemployment. He was disturbed that present gov. have made this happen, like the NAIRU was an law of nature that couldn’t be broken. The economic high priests with divine access have consulted the economic Gods and got the message we have to obey to. Otherwise the economic Gods will strike in vengeance and turn us into a Zimbabwe clone.

Peter: I have a question about QE. I read somewhere that the new reserves created by the FED can be withdrawn by banks and converted into cash, is this possible?

Banks routinely exchange reserves for currency and vice versa. Reserves remain in the FRS for interbank settlement. Currency is used in the economy to settle accounts directly without interbank settlement. This is simply about how transactions are settled.

Tom, if banks can exchange reserves for cash then how boosting reserves would be different from printing money? If Bernanke credits banks with 600B of reserves, they can convert into cash right away, am I wrong?

NAIRU seems to be part of the justification of the growth at any cost mindset which is unsustainable,at least to any conscious person who hasn’t got their head firmly stuck up their posterior in the general region of self interest.

It seems to be bleeding obvious that part of the unemployment problem is the insane rate of immigration leading to an unsustainable population level.While I support the concept of MMT as being the best way forward I think we also need to get back to thinking through some fundamental problematical behaviours which impact on more than narrow economic interests.

Maybe the views of Hermann Daly and the like need to be considered more carefully.

hi gary,

think we are talking about balance sheet effects netting to zero,

not income or revenue account which is determined by nett interest margin.

bill can correct me on this if im wrong

Peter: Tom, if banks can exchange reserves for cash then how boosting reserves would be different from printing money? If Bernanke credits banks with 600B of reserves, they can convert into cash right away, am I wrong?

Banks can convert their reserves to currency anytime they wish. So what? There is no change in net financial assets. How is that “printing money”?

BTW, the reason that bank convert reserves to vault cash is to meet expected demand for cash at the window. Do you expect lots of people coming to the window to close out their savings accounts to put the cash under the mattress?

@mahaish

Thank you for the reply. That is what I think too – but this ignores really important dynamic, IMO. So what that bank accounts balance out to zero? Economic effects of banks – do not. So called “horizontal” transactions are not really horizontal. Banks are acting like giant money vacuums, it seems – that collect from many and give to a few. So what that they supply credit to the economy – if their net effect is to collect more than they credit?

Goverment should run deficits all the time just to offset this. Or am I missing something?

Banks spend their income as operating expenses, and dividends on shareholders, so they behave like any other profit-seeking business. Accumulation of wealth does increase private sector’s need for net financial assets. But if the government-issued component of our money supply would be larger in relative to private sector’s credit component, then debt levels and interest burden would be lower.

Banks are acting like giant money vacuums, it seems – that collect from many and give to a few.

That’s something along the lines of my thinking. Somehow the velocity of money is slowing down and has been for the last 30 years or so. This is due to successive neo-liberal policy victories. Each policy in itself has incrementally reduced the number of hands a dollar passes through before it ends up in an ultra wealthy bank account. When each dollar gets to it’s final destination it does little except contribute to non-productive asset inflation.

Wage negotiating power has been diminished and business profits have been increasing. In every financial transaction some % of the transaction gets to an ordinary worker and is re-spent quite quickly. The profit mainly gets into ultra wealthy bank accounts and stays there. (That’s why they are wealthy – Through not spending money)

Nationalised utility companies have been privatised in many countries. The profit % that previously got returned to the public sector (and in a way re-spent) is now languishing in a fat cats account.

Pensions outsourced. Another % to cream off and store away in dark places. Growth in credit cards and auto loans – more cream for the cat. Financial de-regulation etc etc.

Add to this tax avoidance scams and some pullback of progressive taxation. There something badly wrong with system that needs to be address via aggressive tax reform and re-nationalisation of some key monopolies.

Puzzle: But if the government-issued component of our money supply would be larger in relative to private sector’s credit component, then debt levels and interest burden would be lower.

This is why the rentier class loves “fiscal responsibility” for governments. The more positive the government budgetary balance, the more the private domestic sector has to borrow to maintain its standard of living, absent an offsetting external balance. This translates to more financial rent for the rentiers.

“We usually don’t believe it’s our right to e.g. eradicate people that is not productive because it’s economically sound, but “we” obviously think it’s right to condemn a certain percent of the people to unemployment and misery because a unproved economic dogma say it will prevent inflation”

In a right-minded society we should state that we need something better than NAIRU because clearly people are suffering and 30 years of supply side nonsense hasn’t eliminated that.

Now either NAIRU is incorrect and we can get down to true transistional unemployment arrangements, or NAIRU is correct in which case the society should compensate properly those who are suffering because the system imposed is conceptually inadequate for their needs. Clearly there must be some greater benefit elsewhere for that system to be imposed in the first place – so transfer payments from that benefit to the disadvantaged are obviously just and correct.