These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

My Op Ed in the mainstream Japanese business media

It’s Wednesday and my blog-light day. Today, I provide the English-text for an article that came out in the leading Japanese business daily, The Nikkei yesterday on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to the pandemic. Relevant links are provided in the body of the post. The interesting point I think is that ‘The Nikkei’ is the “the world’s largest business daily in terms of circulation” and has clear centre-right leanings. The fact that they are interested in disseminating ideas that run counter to the mainstream narrative that the centre-right politicians have relied on indicates both a curiosity that is missing in the conservative media elsewhere, and, the extent to which MMT ideas is becoming more open to serious thinkers. I have respect for media outlets that come to the source when they want to motivate a discussion on MMT rather than hire some hack to write a critique, which really gets no further than accusing MMT of being just about money printing.

Article in Nikkei

I was invited recently by the economics editor of – Nikkei, Inc – which own ‘The Nikkei’ newspaper, the prestigious Japan-based daily which is “the world’s largest business daily in terms of circulation”, to write an opinion piece about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to the pandemic.

Nikkei, Inc also own the London-headquartered Financial Times and various TV networks in Japan.

The article – 雇用創出・教育へ投資果敢に コロナ危機と財政膨張 – appeared yesterday (December 22, 2020) in their – 経済教室 (Economic Class) columns where authors help readers understand new ideas.

The title literally translated means – Investing in job creation and education boldly – Corona crisis and fiscal expansion

Thanks very much for their invitation.

For Japanese readers, here is a snapshot (picture) of the article. The link above will take you to a readable format of the article (which is behind a paywall).

For non-Japanese readers, the English text that I sent the publisher follows. I had 1250 words. The heading that follows was my original title, although when one writes Op Ed articles, the title is also the choice of the editors of the media outlet.

Also, I can update those who are interested and have sent me inquiries – the Japanese government fellowship that I have been awarded for 2021 and which I was due to take up residency in Japan in February 2021 will be deferred until later in 2021 as a result of all the travel restrictions associated with the coronavirus.

I anticipate to be in Japan for two months from October 2021 if all things go to plan. It will be a very exciting period to work with researchers in Kyoto and Tokyo and interact with the policy debate.

My Japanese is improving!

The paradigm shift in macroeconomics – Modern Monetary Theory

The sequence of crises – 1991 recession, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and, now the pandemic – has exposed the deficiencies of mainstream macroeconomics and focused attention on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), as the rival paradigm.

We have entered a new era of fiscal dominance as policy makers discard their reliance on monetary policy to stabilise economies.

Even the IMF acknowledge that “Central banks … have facilitated the fiscal response by … financing large portions of their country’s debt buildup”, which has “helped keep interest rates at historic lows”.

This policy shift is diametric to what mainstream macroeconomists have been advocating for decades as they repeatedly warned that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster.

However, their predictions have been dramatically wrong and provide no meaningful guidance to available fiscal space nor the consequences of these policy extremes for interest rates and inflation.

Japan’ experience is illustrative.

It embraced the neoliberal private credit excesses in the 1980s, which caused the 1991 property collapse.

The government’s response pushed economic policies to the extreme of conventional limits – continuously high deficits, high public debt, with the Bank of Japan buying much of it.

Mainstream economists predicted rising interest rates and bond yields, accelerating inflation and, inevitably, government insolvency.

All predictions failed.

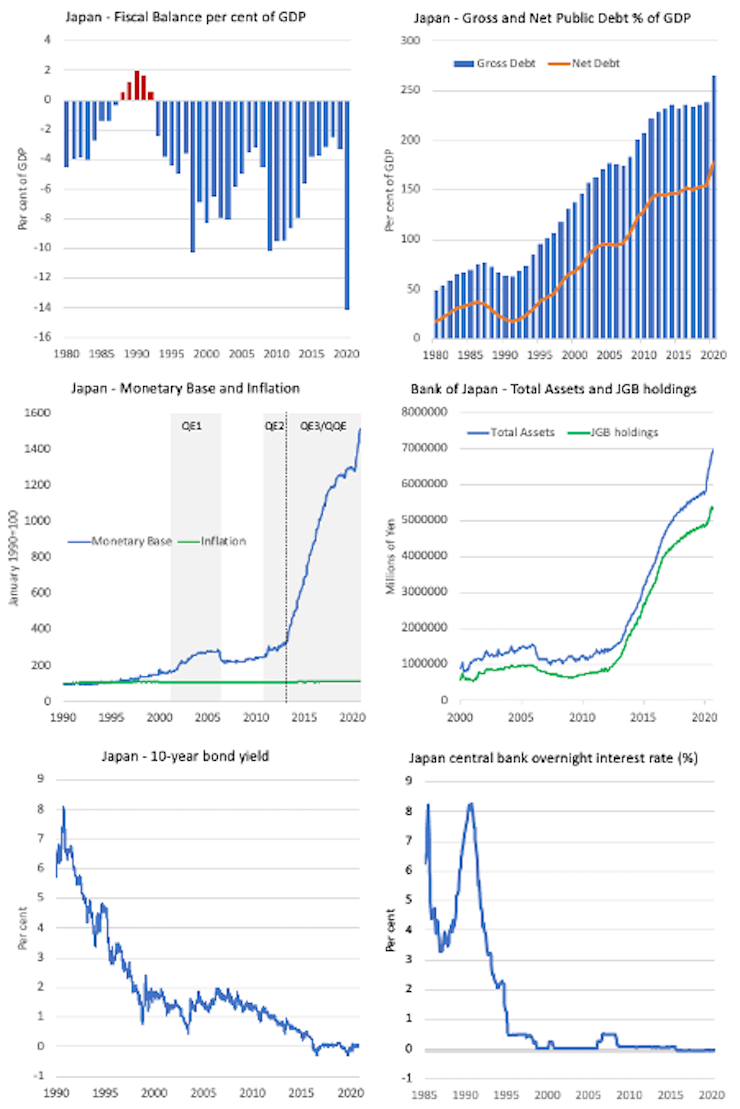

Japan has maintained low unemployment, low inflation, zero interest rates and strong demand for government debt (see graphic).

I provided this graph to The Nikkei which summarises the macroeconomic fiscal and monetary data.

Similar predictions were made during the GFC, when many governments followed the Japanese example.

They again failed because the underlying economic theory is wrong.

Austerity-obsessed governments, applying that flawed theory, forced their nations to endure slower output and productivity growth, elevated and persistent unemployment and underemployment, flat wages growth, and rising inequality.

MMT has consistently advocated a return to fiscal dominance and disabuses us of the claims that fiscal deficits are to be avoided.

MMT defines fiscal space in functional terms, in relation to the available real productive resources, rather than focusing on irrelevant questions of government solvency.

Most of what has been written in the media about MMT is misleading and seems content to dismiss it as ‘money printing’, which to the critics leads to inflation.

However, rather than being some sort of policy regime, MMT is, in fact, a lens which provides a superior understanding of our fiat monetary systems, particularly the capacities of currency-issuing governments.

To operationalise an MMT understanding as policy one has to overlay a set of values. Most policy choices that are couched in terms of ‘financial constraints’ are, in fact, just political or ideological choices.

The fiat money era began when US dollar gold convertibility ended in 1971.

This opened fiscal space for currency-issuing governments because the Bretton Woods requirements to offset spending with taxation and/or borrowing were no longer binding under floating currencies.

There is thus no financial constraint on government spending. Unlike households who use the currency and are financially constrained, a currency-issuing government cannot run out of money.

It can buy any goods and services that are available for sale in its currency including all idle labour.

Mass unemployment becomes a political choice.

MMT allows us to traverse from obsessing about financial constraints and all the negative narratives about the need to ‘fund’ government spending, to a focus on real resource constraints.

It focuses on how policy advances desired functional outcomes, rather than the size of the deficit.

To maximise efficiency, government should spend up to full employment.

The fiscal outcome will then be largely determined by non-government saving decisions (via automatic stabilisers).

The only meaningful constraint is the ‘inflationary ceiling’ that is reached when all productive resources are fully employed.

Mainstream economists will claim that they knew this all along because, in their words, governments can always ‘print money’, but, should not, because it is inflationary.

MMT demonstrates how this reasoning and terminology is erroneous.

First, all government spending is facilitated by central banks typing numbers into bank accounts.

There is no spending out of taxes or bond sales or ‘printing’ going on.

Elaborate accounting and institutional processes, which make it look as though tax revenue and/or debt sales fund spending, are voluntary arrangements that function to impose political discipline on governments.

Second, all spending carries an inflation risk.

If nominal spending growth outstrips productive capacity, then inflationary pressures emerge. Government spending can always bring idle resources back into use, without generating inflation.

At full employment, a government wishing to increase its resource use has to reduce non-government usage.

By curtailing private purchasing power, taxation, while not required to fund spending, can reduce inflationary pressures.

Many commentators then argue that MMT economists are naïve because it is politically difficult to impose higher taxes (or spending cuts) to tackle inflation.

But governments regularly use discretionary fiscal cuts under the guise of fiscal consolidation. Japan’s sales tax increases exemplify this.

The harsh austerity that many nations introduced after the GFC is another example.

Further, many inflationary triggers do not require contractionary demand policies: for example, changes to administrative prices (indexation arrangements), and, regulative shifts when market power is abused.

Governments should always anticipate sectoral bottlenecks and implement skill development policies to sustain labour requirements.

Large-scale public works that add useful infrastructure can also be scaled to meet changing economic conditions.

Overall, given the scale of the crisis, there is little prospect of excessive demand driving inflation in the coming years.

There is also little prospect of a 1970s-style stagflation.

Governments wrongly responded to the politically-motivated supply-shock (oil price hikes) with contractionary demand policies when they should have fast-tracked energy substitution technologies.

More extreme supply shocks explain the hyperinflation of 1920s Germany and modern-day Zimbabwe, both of which are regularly, but erroneously, claimed to demonstrate the danger of fiscal deficits.

The Zimbabwean government’s confiscation of highly productive white-run farms to reward soldiers, who had no experience in farming, caused farm output to collapse, which then damaged manufacturing.

Even with fiscal surpluses, the hyperinflation would have occurred such was the depth of the supply contraction.

What about quantitative easing?

When central banks embarked on large scale government bond buying programs, mainstream economists predicted accelerating inflation.

Indeed, central bankers justified QE as a way to boost inflation, which has been systematically below their price stability targets.

While these bond-buying programs effectively funded fiscal deficits, no inflation resulted because any increase in spending did not push the economy beyond resource constraints.

Mainstream macroeconomics also assert that bank lending is reserve-constrained and competition by government deficits for scarce savings drives up rates and ‘crowds out’ more productive private spending.

In the real world, bank lending is only limited by the credit-worthy borrowers that seek loans. Further, central bankers can maintain yields and interest rates at very low levels indefinitely to suit their policy purposes.

Bond markets can only determine yields if governments allow them to.

MMT economists have always considered that fiscal surplus obsessions were unjustified and underpinned destructive policy interventions. Now, as never before, the scale of the socio-economic-ecological challenges before us requires a rejection of these obsessions.

Meeting these challenges will require significant fiscal support over an extended period. Any premature withdrawal of support will worsen the situation.

MMT shows that the problem into the future will not be excessive deficits and/or public debt or inflation.

Rather, the challenge is to generate productivity innovations derived from investment in public infrastructure, education and job creation as our societies age.

Mainstream economic theory has shown time and again that it cannot effectively tackle the challenges facing the world today.

Music – Broken Wings – John Mayall

This short song – Broken Wings – was Track 5, side B on the – The Blues Alone – album, which John Mayall released in November 1967 on the Ace of Clubs Records label.

This was the first full album I ever bought in my early teenage years with my paper round money. The Ace of Clubs label was great because they were (from memory) $1.99 instead of the usual price for a long playing disk of $4.95.

The album followed pretty well straight after he released – Crusade – his third studio effort which marked the appearance of Mick Taylor (just before he took up with the Rolling Stones).

Mayall had a habit of falling out with his guitar players or bassists – Eric Clapton left the Bluesbreakers, then his replacement, the mighty Peter Green left, bass player John McVie left, and then Mick Taylor. Quite a lineup. Fortunately the dissidents (Green and McVie) formed the first version of Fleetwood Mac and we know what that produced before the band turned to pop.

On this album, John Mayall played all the instruments barring the drums, which were provided by the magnificent Keef Hartley whose own recording career is worth getting acquainted with.

Not only did John Mayall play most of the instruments, he also designed the sleeve notes and cover art for the album, which featured himself playing what I believe was a home made guitar.

So on The Blues Alone he could only really argue with himself.

I loved this track (still do) and fell in love with Hammond B3 organs and always wanted one except I never had a place big enough to store it and guitars took my attention away.

Anyway, mellow out and enjoy the artistry.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

A great article! And congratulations to you Bill for being invited to publish in the Nikkei, a leading business newspaper. It is a big recognition of your life long dedication to MMT and for all the proponents too. Perhaps, it’s also a pre-welcome for your visit in disguise. I hope there will be many more publications like this in the months and years to come, so people around the world will have a clearer perspective/lens for creating better public policies, as well as helping to reduce fake news or economic pseudo-theories.

I hope to see your FT op ed very soon.

Is it not passing strange that The Nikkei aren’t totally familiar with the source of money and the involvement of central banking via the activities of Richard Werner in Japan in the mid-late 1990s?

Werner coined the expression Quantitative Easing /QE way back then and his exploits and involvement with Japanese central banking are documented in his 2003 Japanese best selling book, Princes of the Yen, and the subsequent 2014 documentary of the same name (available free online).

I see Richard Werner as similarly important to the MMT founders in understanding the realities of money, economics and banking and hence what becomes possible because of that.

I thought Werner distrusted government and only advocates cutting up the large banking sector into small banks to avoid a new GFC and maybe a Keen-like debt jubilee when the private debt ratio becomes unsustainable and not continuous management by the central bank but I could be wrong.

Anyway, I think this is a fine article, written very much what I would think the Japanese like to read: clear, concise, structured, almost like a long haiku if that would exist. Great stuff.

Carol,

I’m sure that Bill and the FT will coincide before too long.

There are many FT readers who already appreciate the basis of MMT theory and its precise logical outcome.

Where the hesitancy arises is possibly due to a cynical appreciation of how markets actually work – something that occasionally makes MMT’s condemnation of right wing economics sound as though there is an alternative fairytale solution.

Bill’s aware of the accusation of MMT being associated with a touch of naivety.

@Goggs. Perhaps when they put Wolf out to grass.

Carol,

I think generally, MMT will take universal hold when the world accepts that competitive markets and enlightened social values have in essence a basic incompatibility.

That change in society means perhaps a lengthy process (originating fundamentally with post WW2 welfare frameworks) that entails adapting to a more civilised form of competitive mercantile behaviour.