I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

The case against free trade – Part 3

This blog continues my mini-series of free trade. In Part 1, I showed how the mainstream economics concept of ‘free trade’ is never attainable in reality and so what goes for ‘free trade’ is really a stacked deck of cards that has increasingly allowed large financial capital interests to rough ride over workers, consumers and undermine the democratic status of elected governments. In Part 2, I considered the myth of the free market, the damage that ‘free trade’ causes’. The aim of this mini-series is to build a progressives case for opposition to moves to ‘free trade’ and instead adopt as a principle the concept of ‘fair trade’, as long as it doesn’t compromise the democratic legitimacy of the elected government. This is a further instalment to the manuscript I am currently finalising with co-author, Italian journalist Thomas Fazi. The book, which will hopefully be out soon, traces the way the Left fell prey to what we call the globalisation myth and formed the view that the state has become powerless (or severely constrained) in the face of the transnational movements of goods and services and capital flows. In this blog (Part 3 and final) I consider the concept of ‘fair trade’ as an alternative to the current situation where modern democracies demonstrate an unwillingness to resist the ever-increasing demands of global capital to cede democratic legitimacy in favour of corporate profits.

Previous posts in this series:

1. The case against free trade – Part 1

2. The case against free trade – Part 2

The myth of free trade – continued

In Part 2, I highlighted how trading nations built up their industrial strength (I used Korea as an example). Japan is another good example.

It would never have achieved the state of economic development is current enjoys if it had followed the neo-liberal principles and cut public services, privatised public enterprises, imposed fiscal austerity, and introduced widespread deregulation of capital and labour markets.

As Ha-Joon Chang (2007: 3) reminds us:

… had the Japanese government followed the free-trade economists back in the early 1960s, there would have been no Lexus. Toyota today would, at best, be a junior partner to some western car manufacturer, or worse, have been wiped out. The same would have been true for the entire Japanese economy … Japan would have remained the third-rate industrial power that it was in the 1960s, with its income level on a par with Chile, Argentina and South Africa … it was then a country whose prime minister was insultingly dismissed as ‘a transistor-radio salesman’ by the French president, Charles De Gaulle.

[Reference: Ha-Joon Chang (2007) Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism, London, Bloomsbury Press.]

While the active fiscal role of the state has been central to creating the development successes enjoyed by nations such as Korea, Japan, Germany and the like, there is another reality that the ‘free trade’ lobby obscure when they quote out of mainstream economics textbooks and call for liberalisation.

Even though there were agreements relating to international trade arrangements (embodied in the aftermath of the Second World War as the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), which gave way to the creation of the WTO on January 1, 1995, the liberalisation achieved was heavily laced with continued state intervention and protectionist policies.

There has been an almost dichotomised development process among rich and poor nations, which goes back to the colonial era. The poorer nations (typically under colonial rule) had ‘free trade’ forced upon them with concomitantly poor outcomes, while the colonial powers adopted protectionist positions (Chang, 2007).

Further, while tariffs have come down under successive rounds under the GATT and then the WTO, the global trading terrain has been anything but level.

First, rich nations such as the US still maintain a complex array of tariffs on goods attempting to enter its borders. Japan, for example, maintains a highly protectionist stance with respect to its primary products (particularly against rice imports). These cases are generalised across most nations.

Second, as Ha-Joon Chang notes (2007: 9):

These countries did significantly lower their tariff barriers between the 1950s and the 1970s. But during this period, they also used many other nationalistic policies to promote their own economic development – subsidies (especially for research and development, or R&D), state-owned enterprises, government direction of banking credits, capital controls and so on. When they started implementing neo-liberal programmes, their growth decelerated. In the 1960s and the 1970s, per capita income in the rich countries grew by 3.2% a year, but its growth rate fell substantially to 2.1% in the next two decades.

The reality is for all to see. Economic growth has fallen on average as the neo-liberal regime has been extended. Where so-called ‘liberalisation’ has been most acute, this fall has been larger.

The costs of ‘free trade’

In The case against free trade – Part 2 – I discussed the issue of labour standards and concluded that the current practices espoused in WTO rules and guidelines consistently avoid any specific deliberation of worker protection etc.

The WTO maintains its view that low-wage countries attract capital as a result of their comparative advantage and it is this that leads to development. The evidence is not supportive of that belief (see Chang, 2007 for case studies).

The large capital interests resist any inclusion of labour standards in these ‘free trade’ agreements because they know they would undermine their ‘race-to-the-bottom’ strategy of profit capture.

Environmental damage

A major negative consequence of the increased development of so-called ‘corporate farming’ in poorer nations has been the environmental damage that is caused.

Once again the problem is complex. The aim of economic development is to reduce (and eliminate) poverty but within an environmentally sustainable frame.

However, poverty, in itself, can undermine environmental sustainability. For example, to meet the demands of the World Bank to pay back debts sustainable agricultural practices have been replaced by export-led farming and widescale deforestation in many nations (for example, Nepal).

The evidence is in about the way in which international organisations such as the IMF and the World Bank exploit poverty, which then leads to disastrous environmental outcomes.

These organisations have pushed huge levels of debt onto less developed nations in the name of export-led growth, which is a partner to the neo-liberal ‘free trade’ narrative.

They have also forced these nations to slash public services, privatise public assets and engage in extensive deregulation (particularly in the area of capital flows).

For example, in the 1980s, the African nation of Mali was placed under IMF and World Bank structural adjustment programs where poverty and hardship was deliberately exacerbated by privatisation, cuts to government employment and wages, and decimination of its public education system.

IMF austerity was at the forefront of years of political instability and eventually, once the IMF had the ‘man’ in place who would do their bidding without asking questions, it was declared a model nation by the Washington organisation.

Foreign investment returned to boost the cotton industry but most of the returns courtesy of the IMF privatisation policies go to foreigners and living standards remain low for the locals.

More than 50 per cent of people in Mali are poor. There is gross violations of human rights and a trend over the last decades has been for people to abandon their children in the poverty-entrenched cities because they cannot care for them.

The example of Mali is not isolated. It is the norm when the IMF and the World Bank is involved.

The recent conflict in India involving the proposal to build a coal-fired power plant in Sompeta, which would have destroyed the local sustainable fishing and farming industry. The plant would have taken over valuable wetlands that is at the heart of community sustainability.

Local activists campaigned in 2010 and met with massive police resistance. There were deaths among the protesters. Eventually, the company was forced to abandon its planned development as the local government decreed the land could not be used for that purpose.

However, the struggle goes on there.

The OK Tedi disaster is another example of how multinational corporations who profit from extracting resources from less developed nations largely evade proper scrutiny of the environmental damage they create and the disruption this damage causes local communities.

BHP reneged on the original requirements that protective infrastructure (a tailings dam) be built.

The same company encored recently with the Bento Rodrigues dam disaster and will likely evade paying the full cost of their negligence.

The WTO has also taken decisions which undermine environmental sustainability. In February 2016, it ruled against Indian government support for its emerging solar energy industry. The WTO claims that the so-called domestic content requirements (DRC) that the government had imposed on all new solar installations contrivened its ‘competition’ rules.

The Indian suppliers believed that imported solar panels were being ‘dumped’ on the local market at below production costs (mostly from China) which serves to undermine local industry development.

Corporate farming (agri-business) is also implicated in environmental degradation within less developed countries as part of the ‘free trade’ mantra.

There are many dimensions to this including deforestation, genetic engineering, increased use of dangerous pesticides, irrigation schemes that deplete aquifers, among the other problems encountered.

The WTO has no coherent rules that restrict imports from nations that engage in poor environmental practices. They claim that (Source):

… no specific agreement dealing with the environment. However, the WTO agreements confirm governments’ right to protect the environment, provided certain conditions are met, and a number of them include provisions dealing with environmental concerns.

But in seeming to provide some scope for environmental activism by national governments, the WTO claims that (Source):

Environmental requirements can impede trade and even be used as an excuse for protectionism.’

This is a consistent position of the WTO – any imposts on multinational firms, whether they be in the area of labour or environmental standards, are just trojan horses for “protectionism”.

The WTO responds to calls for trade restrictions if environmental damage is likely to result from production by claiming that:

… measures designed to meet these objectives could hinder exports. And they agree that sustainable development depends on improved market access for developing countries’ products.

They also argue that “environmental standards applied by some countries could be inappropriate”, meaning that a nation does not have the right, under WTO thinking, to determine its own standards.

Further, they adopt the standard mainstream economics positions that the solution to pollution and environmental damage is to create more growth (and damage) to generate the resources necessary to combat the damage (Source):

WTO members are convinced that an open, equitable and non-discriminatory multilateral trading system has a key contribution to make to national and international efforts to better protect and conserve environmental resources and promote sustainable development.

The concession recognised is that nations may enter into so-called “environmental agreements” where they agree to share environmental standards. Trade between the nations is then conditioned by those agreements.

However, they consider it problematic “when one country invokes an environmental agreement to take action against another country that has not signed the environmental agreement”.

A classic case involved the dispute between the US and Mexico over import embargoes against Mexican tuna in 1991. Under GATT rules, one nation could not “take trade action for the purpose of attempting to enforce its own domestic laws in another country – even to protect animal health or exhaustible natural resources”.

The GATT ruled in 1991 that the US embargo was illegal even though the Mexican regulations allowed productive practices that violated US laws.

The GATT said that (Source):

If the US arguments were accepted, then any country could ban imports of a product from another country merely because the exporting country has different environmental, health and social policies from its own. This would create a virtually open-ended route for any country to apply trade restrictions unilaterally – and to do so not just to enforce its own laws domestically, but to impose its own standards on other countries. The door would be opened to a possible flood of protectionist abuses. This would conflict with the main purpose of the multilateral trading system – to achieve predictability through trade rules.

The import of this ruling is that the acceptable standards are really a race-to-the-bottom. A nation that attempts to apply its own higher level of standards to restrict imports is prevented under the WTO rules.

That should not be the case.

While the Mexican dispute worked against the wealthier US, the usual situation is that less developed and less powerful nations are trampled on by first world corporate interests.

Even John Gray, who dallied with the New Right in Britain, wrote in 1998 that the push for more deregulated globalisation (masquerading as the ‘free trade’ and the ‘free market’) would be disastrous in its impacts, which include vast environmental damage, increasing poverty rates, and deepening ethnic divisions.

Gray argued that the ‘free trade’ movement was an Anglo-American contrivance designed to satisfy the needs of financial capital and could never be seen as anything ‘natural’.

He showed how at all times through history humans created markets but conditioned them via social norms, including fairness and inclusiveness.

Gray (1998: 28-29) argued that the costs of following this blind ‘free market’ route have been enormous:

According to the Thatcherite understanding of the role of the state, its task was to supply a framework of rules and regulation within which the free market – including, crucially, the labour market – would be self-regulating. In this vision the role of trade unions as intermediary institutions standing between workers and the market had to be altered and weakened. Employment law was reshaped. The contemporary model that informed these changes throughout was the American labour market, with its high levels of mobility, downward flexibility of wages and low costs for employers.

Partly as a result of these policies, there was an explosive increase in part-time and contract work. The bourgois institution of the career or vocation ceased to be a viable option for an increasing number of workers. Many low-sill workers earned less than the minimum needed to support a family. The diseases of poverty – TB, rickets, and others – returned.

So while our conception of a market is built on a set of social institutions which were designed to allow it to work in the wider interests, Gray (1998: 29) argued that:

The innermost contradiction of the free market is that it works to weaken the traditional social institutions on which it has depended in the past – the family is a key example.

Fair Trade principles

At the end of the APEC leaders’ summit held in Lima, Peru (November 19-20), US President Obama extolled the virtues of what he called ‘free trade’.

The full transcript is available – Press Conference by President Obama in Lima, Peru

President Obama said:

When it comes to trade, I believe that the answer is not to pull back or try to erect barriers to trade. Given our integrated economies and global supply chains, that would hurt us all. But rather the answer is to do trade right, making sure that it has strong labor standards, strong environmental standards, that it addresses ways in which workers and ordinary people can benefit rather than be harmed by global trade.

This is the nub of the debate.

We all typically benefit from trade IF it doesn’t violate democratic choices made by citizens and expressed through their national government policies in areas such as:

1. Working conditions – wages, safety, hours.

2. Rights to association and right to strike – formation of trade unions etc.

3. Consumer protection – safety, ethical standards, quality of product or service etc.

4. Environmental standards.

Under those conditions, what we actually would have is ‘fair trade’ rather than the type of trading arrangements embodied in the raft of so-called ‘free trade’ agrements.

But the problem arises when we try to achieve a cultural intersection as to how to define fairness in these areas.

It is quite clear, for example, from an examination of the way different countries allow their labour markets to adjust to economic slowdowns, that the concept of fairness is slippery.

The economies that avoided the plunge into high unemployment in the 1970s maintained what Paul Ormerod (1994: 203) described as a “sector of the economy which effectively functions as an employer of last resort, which absorbs the shocks which occur from time to time, and more generally makes employment available to the less skilled, the less qualified”.

[Reference: Ormerod, P. (1994) The Death of Economics, London, Faber and Faber.]

Ormerod acknowledged that employment of this type may not satisfy narrow neoclassical efficiency benchmarks, but notes that societies with a high degree of social cohesion have been willing to broaden their concept of ‘costs’ and ‘benefits’ of resource usage to ensure everyone has access to paid employment opportunities.

He argued that countries like Japan, Austria, Norway, and Switzerland were able to maintain this capacity because each exhibited “…a high degree of shared social values, of what may be termed social cohesion, a characteristic of almost all societies in which unemployment has remained low for long periods of time” (Ormerod, 1994: 203).

He is talking about concepts of fairness (equity) and the collective will to ensure political choices are made which favour maintaining adequate levels of employment.

In nations such as Australia or the US, governments are less willing to ensure employment levels are sustained in the face of drops in economic activity.

There are many ways in which differences

What is Fair Trade?

The World Fair Trade Organisation definition is:

Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South.

Which really does not say much.

The so-called 10 Principles of Fair Trade are:

Principle One: Creating Opportunities for Economically Disadvantaged Producers

Principle Two: Transparency and Accountability

Principle Three: Fair Trading Practices

Principle Four: Payment of a Fair Price

Principle Five: Ensuring no Child Labour and Forced Labour

Principle Six: Commitment to Non Discrimination, Gender Equity and Women’s Economic Empowerment, and Freedom of Association

Principle Seven: Ensuring Good Working Conditions

Principle Eight: Providing Capacity Building

Principle Nine: Promoting Fair Trade

Principle Ten: Respect for the Environment

It is fine to establish ‘fair trade’ principles and reject commercial arrangements where, for example, corporate importers exploiting poor farmers because of the imbalance in market power between the two groups.

We can clearly agree that as consumers in high income nations we will not drive prices down to levels that do not allow the farmers in the low-income nations some desired income growth in line with global goals to eliminate poverty.

But then mainstream economists claim that such practices are self-defeating because they promote overproduction, which undermines the suppliers via price drops.

The WTO should be replaced with an all-encompassing multilateral body that is charged with establishing relevant labour and environmental standards to regulate trade.

While it is recognised that nations in different periods of development will have different productive methods, working standards that are acceptable across cultures can be devised.

For example, in Australia road building in highly mechanised with high capital-to-labour ratios relative to Africa, where labour intensive methods are better because they can produce the same standard of output with more labour.

However, within these differences, some standards remain common – the right to association, the right to adequate rest and breaks, the right to holidays, the right to fair pay, the right to strike.

It is beyond the scope of this blog to define all the operational detail. But the general principle is clear – trade should not be allowed if it violates the principles listed above.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) trade principles

In a materialistic sense of well-being, imports provide benefits to a nation (goods and services otherwise unattainable), while exports are a cost (real resources are sacrificed and used by foreigners rather than the nation).

Adopting the view that imports are good doesn’t undermine our critique of ‘free trade’. Indeed, it strengthens it.

Some commentators might think that this starting point then militates against the advocacy for such things as import controls. The answer is that even though, in general, exports are a cost and imports are a benefit, the framework in which we make those assessments is multi-dimensional and extends the concept of material progress in ways that mainstream economics typically ignores.

For example, a commercial transaction that is only considered in terms of the use value that the consumer receives may involve massive damage to the producing community. So while an imported good or service might be seen in narrow terms to be a ‘good’ for the consumer, once we broaden our assessment of the costs and benefits of the overall chain of production and consumption a more nuanced view will emerge.

By adopting principles that allow the actual costs, including damage to the environment, destruction of local sustainable industry, damage to human dignity of unfair work practices etc, the benefits of the import to a consumer will pale into insignificance relative to the costs of the producers.

In those cases, import controls may be justified to limit the damage to the less developed nation, despite the material benefits to the more developed nation being obvious.

Further, there is a compositional aspect to the exports are a cost and imports are a benefit classification. In the case of primary commodity exporting nations such as Australia, the costs involved in mining our vast stores of iron ore maybe low, given the alternative use of the resource within Australia is limited.

Free Trade Agreements

The US president-elect announced today that one of the first things he will do once in office is withdraw from the so-called Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP).

The TPP (like many of these agreements) represent the cutting edge of the ‘free trade’ lobby’s attempt to undermine the capacity of elected states to deliver on their mandate to their electorates, and, instead, hand over almost absolute power over the state to international corporations.

The TPP is being pushed under smokescreen of ‘free trade’, which is one of those classic neo-liberal con jobs like deregulation, privatisation, public-private partnerships and other ruses that imply that self-regulating private markets will deliver maximum wealth growth to all.

We have had difficulty even accessing what the TPP involves. The governments involved have pleaded ‘commercial-in-confidence’ as their reason for preventing a full public debate on the proposed TPP. They hide the negotiating details from us and then tell us that it is in our best interests for them to urgently sign of on it without the normal political oversight.

But the problem is that these agreements give corporations priority over a state and the citizens that the state represents.

In terms of what we know about the TPP (via Wikileaks mainly), the aim of the treaty is to allow international corporations more freedom to operate across national borders without the usual oversight from the legislative environment imposed by the state.

The areas that the signatory states will lose the capacity to regulate include labour market regulations (job protection, minimum wages, etc), the cost of medical supplies, financial market oversight, environmental protection, and standards relating to food quality.

The controversial aspect of these agreements surrounds the so-called Investor State Disputes Settlement (ISDS) clauses, which set up mechanisms through which international corporations can take out legal action against governments (that is, against elected representatives of the people) if they believe a particular piece of legislation or a regulation undermines their opportunities for profit.

It is that crude. Profit becomes prioritised over the independence of a legislature and the latter cannot compromise the former. Our values have really become skewed in the ‘dark age’.

In other words, a democratically-elected government is unable to regulate the economy to advance the well-being of the people who elect it, if some corporation or another considers that regulation impinges on their profitability.

Corporation rule becomes dominant under these agreements, which usurp any WTO rules.

The agreements create what are known as ‘supra-national tribunals’ which are outside any nation’s judicial system but which governments are bound to obey.

The make-up of the tribunals is beyond the discretion of a nation’s population and, as far as we know, will be heavily weighted under the TPP by the corporate lawyers and other nominees. The notion of accountability disappears.

These tribunals can declare a law enacted by a democratically-elected government to be illegal and impose fines on the state for breaches.

With heavy fines looming, clearly states will bow to the will of the corporations. Corporation rule!

There have already been some astounding decisions in these ISDS under other agreements, which have denied governments the right to introduce policies regarding environmental protection (for example, toxic waste safeguards, forestry management processes, etc).

Clearly, the secrecy – in which the TPP is being finalised is a reflection of its toxic nature. The governments know that if the details leak out there will be an outcry and their political positions will become an object of focus.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) keeps a database on – Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) – which they say is “currently being redesigned and updated”. The so-called “reduced version of the database” makes for interesting analysis.

Since 1987, 24 per cent of the 608 cases taken out have been resolved in favour of the state being sued. There are still 58 per cent of the cases outstanding.

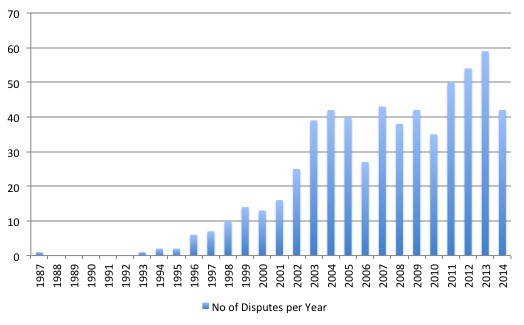

Here are some summary data that I gleaned from the database. The first graph shows the escalation in the ISDS cases since 1987.

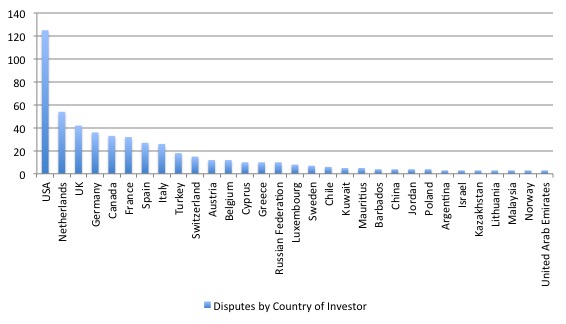

The next graph shows the top 30 countries of investors who sued various states. The US clearly dominates with American corporations taken action in 21 per cent of the total cases. Dutch firms also appear to be particularly litigious.

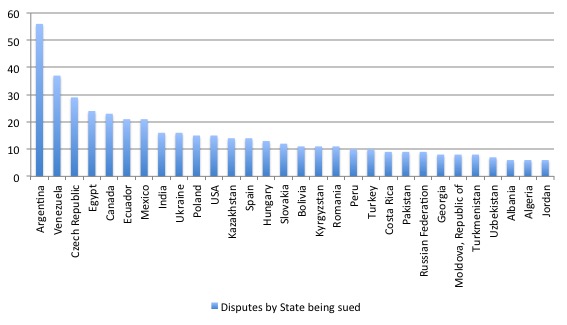

The final graph shows the disputes by state being sued for the top 30 states. Argentina is involved in 9.2 per cent of the total cases followed by Venezuela (6.1 per cent), and the Czech Republic (4.8 per cent).

What evidence is there that these agreements advance well-being? Answer: none. In fact, the evidence so far produced of prior agreements (noted above) tends to conclude that the operation of these agreements undermines the national welfare.

The Australian Productivity Commission released its latest – Trade and Assistance Review 2013-14 – on June 24, 2015.

The APC can hardly be described as anything other than a pro-market body. Its history is that it began life as the Tariff Board (overseeing the protection system in Australia) and in recent decades, became the government’s free market agency – arguing relentlessly for deregulation and privatisation.

So it is hardly a left-leaning organisation.

Its latest Review studied, among other things, the so-called “Preferential trade agreements”, which Australia has entered into in recent years (with China and Japan). These agreements are similar to what we expect will be in the TPP.

The Productivity Commission concluded that:

Preferential trade agreements add to the complexity and cost of international trade through substantially different sets of rules of origin, varying coverage of services and potentially costly intellectual property protections and investor-state dispute settlement provisions.

… The emerging and growing potential for trade preferences to impose net costs on the community presents a compelling case for the final text of an agreement to be rigorously analysed before signing. Analysis undertaken for the Japan-Australia agreement reveals a wide and concerning gap compared to the Commission’s view of rigorous assessment.

It notes:

1. The “proliferation of preferential trade agreements at the bilateral and regional level (referred to commonly as ‘free trade agreements’) is adding to the complexity and business transaction costs of the international trading system”.

2. The “practical impacts of agreements being entered into by Australia remain unclear and highlight the need for thorough evaluation of the negotiated agreement text prior to their signing.”

3. “In substance, the devil resides in the detail of these agreements and full and transparent analysis is not afforded to the final texts for many of them.”

4. “current assessment processes in Australia fall well short of what is needed to adequately assess the impacts of prospective agreements.”

5. “Current assessment processes do not systematically quantify the likely costs and benefits of negotiated texts to an agreement, fail to consider the opportunity costs of pursuing preferential arrangements compared to unilateral reform and ignore the extent to which agreements actually liberalise existing markets”.

6. “that services provisions negotiated under the ASEAN-Australia- New Zealand agreement added little if anything, to those already afforded by services commitments under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)” but exposed the Australian state to unnecessary risks.

Australia, for example, went down this route of secrecy previously, when the national government signed the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement and the Japan-Australia Free Trade Agreement, which effectively prevented the elected parliament from legislating against any of the provisions in the respective treaties.

In the case of the North Asian free trade agrements (Japan, South Korea and China), the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade concluded that the overall impact for Australia of these three agreements will be:

1. An increase of GDP of 0.05 per cent – that is, hardly anything at all.

2. An extra 5,435 jobs between now and 2035 – that is, hardly any impact.

3. Exports to rise by 0.5 per cent, while imports to rise by 2.5 per cent.

[Reference: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2015) Economic benefits of Australia’s North Asian FTAs, Canberra, AGPS.]

It is hard to see how these minimal effects will advance the well-being of citizens in any of the nations involved.

Even worse results are reported for the 2005 Australia-US free trade agreement.

The Productivity Commission also comments on the ISDS activity relevant to Australia. The national government is being sued by an international tobacco company for introducing plain packaging with health warnings. The company claims it undermines its profitability.

The Commission says:

The Australian Government continued defence of its tobacco plain packaging laws in a case brought by Philip Morris Asia in the Permanent Court of Arbitration and a number of countries in the WTO dispute settlement body. This case highlights the potential (and un-provisioned) contingent liability of Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) provisions in trade and investment agreements that confer procedural rights to foreign investors not available to domestic residents. The final outcome of the case is not expected to be known for some time. The ongoing costs to Australian taxpayers of funding the preparation and defence of the tobacco plain packaging legislation, and the ultimate ruling, are unknown, unfunded and likely to be substantial.

In other words, international corporations have more rights than local residents.

The TPP is one component of the corporate intolerance for democratic oversight by states. The agreements are being advanced by neo-liberal governments who think the role of government is to advance the interests of the corporations as a way of increasing wealth.

We already know that the distribution of income and wealth is becoming more skewed as the neo-liberal era continues.

These trade agreements are just dirty scams designed to continue the redistribution of income and wealth to the top end of the distributions and to further neuter the capacity of governments to act independently according to elected mandates.

They line up with fiscal rules, independent fiscal commissions, and the like as key vehicles to suppress our freedoms and choice of legislative environment in which we live.

Conclusion

These so-called ‘free trade’ agreements are nothing more than a further destruction of the democratic freedoms that the advanced nations have enjoyed and cripple the respective states’ abilities to oversee independent policy structures that are designed to advance the well-being of the population.

The underlying assumption is that international capital is to be prioritised and if the state legislature compromises that priority then the latter has to give way.

A progressive agenda would ban these agreements and force corporations to act within the legal constraints of the nations they seek to operate within or sell into.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

28. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost.

29. The metamorphosis of the IMF as a neo-liberal attack dog.

30. The Wall Street-US Treasury Complex.

31. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976.

32. British Left reject fiscal strategy – speculation mounts, March 1976.

33. The US government view of the 1976 sterling crisis.

34. Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well.

35. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976.

36. The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976.

37. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality.

38. The British Left is usurped and IMF austerity begins 1976.

39. Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy.

40. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation.

41. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1.

42. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 2.

43. The case for re-nationalisation – Part 2.

44. Brainbelts – only a part of a progressive future.

45. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 1.

46. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 2.

47. Reducing income inequality.

48. The struggle to establish a coherent progressive position continues.

49. Work is important for human well-being.

50. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 1.

51. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 2.

52. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 3.

53. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 4 – robot edition.

54. Is there a case for a basic income guarantee – Part 5.

55. An optimistic view of worker power.

56. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 3.

57. Reforming the international institutional framework – Part 4.

58. Ending food price speculation – Part 1.

59. Ending food price speculation – Part 2.

60. Rising inequality and underconsumption.

61. The case against free trade – Part 1.

62. The case against free trade – Part 2.

63. The case against free trade – Part 3.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It’s all totally criminal. After “colonising” participating nations and getting them into dollar debt. Creditors come in to soak up assets and leave the citizens permanently impoverished. The IMF comes in and, to use a colourful expression from another blog, bayonets the wounded. All are arms of US hegemony at work., and before them the UK, France and others, Belgium worst of all. The migrant crisis is payback, although they mostly should end up in the USA.

As Steve Keen wrote, a free trade agreement is just one line. All the rest, like 6000 pages in the TPP, are exceptions and regulations over “free” trade. So It cannot possibly be free. The word we want, if there are to be treaties, is Fair Trade. It makes one’s blood boil.

So, what I here you saying is that free trade was designed to satisfy the needs of financial capital while weakening social cohesion, equality and traditional social institutions such as the family, destroying any just compensation for people and leaving financiers more firmly in control of civilization.

Speaking of Trump, we can only hope that he does what he says about the trade agreements. I am reminded of Obama promising to bring sunlight into government. It is amazing the lies he has told and the darkness he has brought on America. I suspect that in any speech he ever gave he only repeated what his benefactors laid out for him and I know that it was all just to deceive us into thinking that he was actually worth a “something”. I quit doing that a long time ago.

While imports are a gain for the importing country,ha choon Ja has pointed out that tarriffs buffers allow domestic industry to develop which in the long term increase domestic industry and enable the country to be a highe r income country(again look at taiwan,s.korea and japan)

This protects growth and develops domestic production capactity .Where as if a nation depended on imports,it would suffer a huge decrease in living standards if there was a foreign exchange shock.

Having sufficient domestic production capacity ensures that a nation will be unaffected by severe currency fluctuations.Think medicine,food,energy,hi-tech equipment,industrial goods,

Which begs the question,what policies should be pursued to ensure high exchange rates so that the domestic population can enjoy favorable terms of trade.(dismissing fixed exchange rates of course and the straight jacket they impose on the fiscal capacity on govt)

having said that I hate wearing sweat shop labor produced clothes,because I hated long hour low pay grueling work,but the cheap clothes boost living standards for the domestic poor.

The ‘effects’ of globalization?

“Know your facts: Poverty numbers

José Cuesta, Mario Negre, Christoph Lakner

07 November 2016

The percentage of people living in extreme poverty around the world has fallen by more than half over the past three decades. But polls show that most people are not only ignorant of this fact, but believe that poverty has increased. This column explores progress towards ending global poverty by 2030, the first of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Poverty figures have fallen around the world since 1990, and there is a broad consensus on the policies needed for further reductions. Eradicating global poverty is achievable, but it is dependent on global and domestic political cooperation.”

Dear Postkey,

If you look into the poverty reduction data country by country you could appreciate how the best examples are not countries that followed the IMF and WTO recipes.

For instance, the gross of poverty reduction is due to China who certainly have beneficed from globalization, but, following its own path and its own pace.

It seems to me that, when looking carefully, the data support the post of professor Mitchell.

“We have had difficulty even accessing what the TPP involves. The governments involved have pleaded ‘commercial-in-confidence’ as their reason for preventing a full public debate on the proposed TPP. They hide the negotiating details from us and then tell us that it is in our best interests for them to urgently sign of on it without the normal political oversight.”

Well, but the full text is right here: http://tpp.mfat.govt.nz/text

There it is written what TPP involves…

“The TPP (like many of these agreements) represent the cutting edge of the ‘free trade’ lobby’s attempt to undermine the capacity of elected states to deliver on their mandate to their electorates, and, instead, hand over almost absolute power over the state to international corporations.”

Barack Obama worked hard to implement the TPP, Hillary Clinton supported it, then she didn’t, and would no doubt have quietly authorised it if she won the Presidency and the Australian Labor Party supports the TPP. Who needs ‘progressive’ parties that treasonously support the ceding of democratic power to big business just as strongly as the right wing free market parties? Any party that supports the TPP with the ISDS protocols deserves zero support and zero votes. Get rid of these traitors!

The working class of most of the developed world, in particular the main English speaking countries, that has been treated so appallingly over the last 30+ years as neoliberalism has metastasised, have been betrayed by the free market right wing political parties and the social democratic/labour parties. Because of this there has been a substantial shift of support of the working class and some of the middle class to the hard right such as UKIP in the UK, Trump in the U.S., One Nation in Australia and various nationalist and racist parties in the rest of Europe. These far right parties will inevitably disappoint in so many areas such as on addressing climate change, curbing the grossly excessive power of big business, equality for all minorities and providing an adequate universal system of education, health care and social support.

The social democratic and labour parties must not move their policy agenda even further to the right in an attempt to regain their traditional voting base but must look at the better social and economic structures that existed before the rise of neoliberalism and promise to restore them, in other words loudly proclaim that neoliberalism, government austerity, totally free trade, totally free markets and ‘trickle down’ monetarism were failed policies. The political and economic structures of the 1970’s combined with embracing worthy technological and economic progress similar to the East Asian, German or Scandinavian economic development model with an interventionist state, within environmental constraints, looks to be the best way forward.

The ALP still clings tightly onto neoliberalism despite appalling and unprecedented levels of wealth disparity, stagnant incomes, very high and rapidly rising real levels of unemployment and underemployment, the ongoing forced destruction of the manufacturing sector and continues to support the drift to a feudal corporate dictatorship.

Jeremy Corbyn however appears to be moving the UK Labour Party down a better path but he may need a new Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer if John McDonnell keeps repeating neoliberal dogma like the need for fiscal discipline.

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/15/john-mcdonnell-labour-must-show-unbreakable-fiscal-discipline

@Postkey Roberto

Best to look at the issue with the accounting realities in mind. Follow the balance sheets.

Globalisation is a homeopathic word we can construe it into many different forms of reasoning.

Its just the cumulative interactions of each nations private sectors with each other and the government sectors likewise.

Someone somewhere must be running a deficit if someone somewhere else is running a surplus. All the hype about China’s great benefits from ‘Globalisation’ versus looking at the reality: You’ve got artificially lower exchange rate (devalued yen) and large government deficits funding the whole show. Nothing miraculous there.

Inevitably when looking at the impacts of trade between A and B you must look at the transitives between the whole set of trading nations {C, D, E, F etc). As much of the analysis impact of ‘free trade’ deals never does this. (usually just assume an infinite stock of rational agents)

Then there is the TPP and others just a ‘free trade’ bumper sticker covering up lawless capitalism dressed up as always as TINA ‘there is no alternative’.

By corollary I can make a sarcastically adamant case could be made for the ‘free market’ rational individuals (presumably the private sector as a whole) to pay ‘no tax’ 😉 Its an unfair barrier that stops trade with my customers. In a globalised world i must have no trade barrier with the customer down the street. Note to self: become a billion dollar corporation and lobby to pay no tax. Hmm wonder how would i go about that 😉

“First they ignore you, then they say you’re mad, then dangerous, then there’s a pause and then you can’t find anyone who disagrees with you.”

Tony Benn