In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Japan GDP growth contracts as politicians fight it out over size of fiscal stimulus

I am travelling today to Tokyo and have little time to write here. But with the latest national accounts data coming out on Monday (November 17, 2025), the discussions within the government are about the size of the fiscal stimulus that will be initiated in the next fiscal round. This The Japan Times article (November 18, 2025) – Extra-big extra budget pushed by some Japanese lawmakers – provides some information. The new Prime Minister is proposing to limit the fiscal shift to an extra 17 trillion yen (about $US110 billion) but a small group within the ruling LDP want the package to be around 25 trillion yen. I think the stimulus should be around 50 trillion yen and there are economists in the financial markets who agree with me. More on that another day. But the current debate is being conducted within the context of the latest – National Accounts – for the September-quarter 2025, issued by the Cabinet Office (November 17, 2025). The economy grew by 1.1 per cent over the last 12 months (down from 2 per cent in the June-quarter). In the September-quarter, GDP shrank by 0.4 per cent, the first negative quarter since the March-quarter 2024. The need for stimulus is clear. The debate is over how much.

The summary results for the September-quarter (seasonally adjusted) were:

- GDP growth: -0.4 per cent for the quarter (down from +0.6); +1.1 per cent annually (down from +2 per cent).

- Private Consumption: +0.1 per cent quarter (previous +1.4); +0.8 per cent annual (previous +0.4).

- Private Residential Investment: -9.4 per cent quarter (previous +0.3); -7.9 per cent annual (previous +2.4).

- Private Non-Residential Investment: +1 per cent quarter (previous +0.8); +3.3 per cent annual (previous +2.3).

- Public Consumption: +0.5 per cent quarter (previous +0.1); +0.5 per cent annual (previous -0.1).

- Public Investment: +0.1 per cent quarter (previous -0.1); -0.1 per cent annual (previous -0.6).

- Exports: -1.2 per cent quarter (previous +2.3); 2.7 per cent annual (previous +6.1).

- Imports: -0.1 per cent quarter (previous +1.3; +1.5 per cent annual (previous +5.0).

- Domestic demand: -0.2 per cent quarter (previous +0.3); +0.8 per cent annual (previous +1.8).

Summary:

1. Growth is faltering.

2. Domestic demand is contracting.

3. Government spending growth increased but not sufficiently to offset the decline in non-government spending growth.

4. Exports declined overall – reflecting the impact of the imposition of tariffs by the US (particularly in the motor vehicle sector).

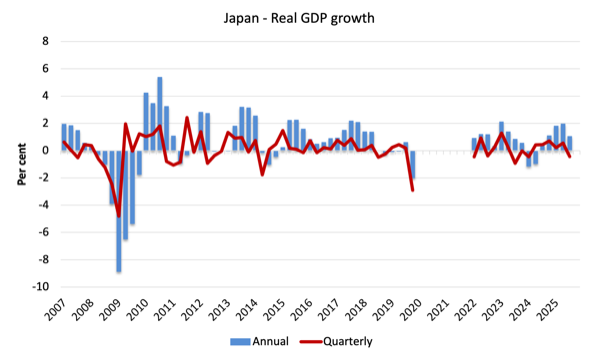

The first graph shows the quarterly and annual real GDP growth rates from the March-quarter 2007 to the December-quarter 2019.

I excluded the observations from March-quarter 2020 to the December-quarter 2023 as they were COVID-19 outliers.

Contributions to growth

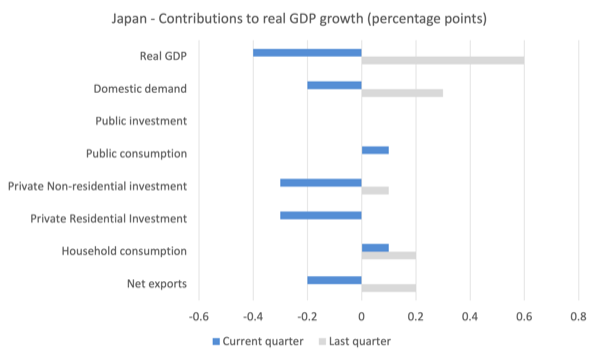

The next graph shows the contributions (in percentage points) to real GDP growth of the major expenditure categories in Japan for the June-quarter 2025 (denoted last quarter) and the September-quarter (denoted current quarter).

Only private and public consumption expenditure provided any growth stimulus.

Government investment expenditure has provided no stimulus for the last 2 quarters.

The decline in export contribution is down to the tariff situation, which saw motor vehicle exports slump significantly.

Previous quarters were biased as a result of the car manufacturers shipping larger volumes of vehicles to the US prior to tariffs taking effect.

There was also evidence that the manufacturers are absorbing the tariff imposition in the margins (that is, cutting prices).

The negative contribution of private residential investment (basically house construction) was due to a regulatory change introduced by the Japanese government which required increasingly strict energy efficiency standards on new housing construction.

The prospect of rules that will make it harder for foreigners to purchase houses in Japan may impact soon but have not yet been introduced in any formal way.

Consumer and Business Confidence

The Japanese Cabinet Office publishes a – Monthly survey of Consumer Confidence.

The latest results, released on October 29, 2025 (for a survey conducted in October 15, 2025) tells us:

1. “The Consumer Confidence Index (seasonally adjusted series) in October 2025 was 35.8, up 0.5 points from the previous month”.

2. All components that influence the Consumer Perception Indices were positive:

Overall livelihood: 34.3 (up 1.1 from the previous month)

Income growth: 40.0 (up 0.6 from the previous month)

Employment: 40.1 (up 0.2 from the previous month)

Willingness to buy durable goods: 28.9 (up 0.1 from the previous month)

This suggests that the household spending is not about to fall apart.

In my recent presentation at the Japanese Diet (November 6, 2025), I argued that cutting or abandoning the sales tax would generate the biggest GDP return given the way that Japanese households respond to the tax hikes.

In Australia, for example, when the federal government introduced a value added tax in 2001, household consumption expenditure didn’t budge much at all because households just went more into debt.

The Japanese households eschew this approach and immediately cut spending after the three sales tax hikes since 1997.

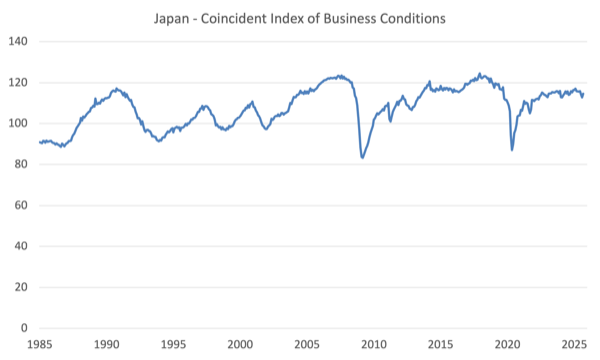

The Cabinet Office also publishes Monthly – Indexes of Business Conditions.

The latest result (November 10, 2025) showed that conditions have declined since the start of 2025, but the September observation suggested the decline was “halted”.

The following graph is their latest time series (since January 1985) of their ‘Coincident Index’, which is explained in this document – Guide for Using Composite Indexes and Diffusion Indexes.

Basically, the “composite indexes mainly aim to measure the tempo and the magnitude (“the volume”) of economic fluctuations”. The “coincident index … coincides with the business cycle, and is used to identify the current state of the economy.”

And:

… increasing the coincident index reflects that the economy is in an expansion phase, and decreasing coincident index reflects that the economy is in a contraction phase. The magnitude of the changes in the coincident index reflects the tempo of the expansion or contraction phases.

The debate over expansion

I most recently discussed the issue in this blog post – Japan – errant fiscal rule is sure to backfire (October 30, 2025).

GDP contracted by 0.4 per cent in the September-quarter 2025.

There were one-off impacts of the new construction regulations which led to a -0.3 points contribution from Private Residential Investment.

But excluding that temporary glitch from our assessments means that overall GDP growth was still negative.

We also have not been able to form a clear idea on the overall impact of the US tariffs, which was clearly negative in the September-quarter 2025.

What the US President will do next is anyone’s guess but it is clear that the Japanese motor vehicle manufacturers have lost some traction in the US market.

Clearly, there is no justification for further interest rate increases and the Bank of Japan should cut rates.

In terms of fiscal policy, the question is not whether to introduce a new fiscal expansion.

It is how large the expansion should be.

The new Prime Minister is receiving advice – ill-informed in my view – that she has to walk a line between stimulating an economy that is going backwards and appeasing financial markets over the size of the fiscal deficit.

That is the usual bluff that the mainstream economists present.

And bluff it is.

The construction is false and leads to poor decision making.

So while some might think that the extra 17 trillion yen that Ms Takaichi is proposing sounds like a lot but given the growing spending (output) gap, it is way too small an injection.

Even the so-called LDP rebels who want a 25 trillion yen injection are being constrained in their thinking by that false dichotomy I mentioned above.

In both cases, a significant proportion of the injection would be returned via increased tax payments from the non-government sector.

Some claim that the rising yields on Japanese government bonds is a sign that the financial markets consider the fiscal deficit is too large and are demanding higher premiums.

That is another false construction.

The slight decline in the demand for JGBs is due to the returns on other financial assets rising in line with the rate hikes that the Bank of Japan has initiated.

It is just an arbitraging effect and has nothing to do with the size of the fiscal deficit.

As I noted in my talk at the Diet a few weeks ago, which was attended by many Members of Parliament, there is no fiscal crisis in Japan and nor will there ever be.

The obsession with fiscal surpluses is flawed and leads to poor decision making.

I argued that there was a vicious cycle in Japan which since the asset price crash in early 1990s had locked Japan into a secular stagnation.

This cycle is characterised by:

1. Excessive retained earnings by Japanese corporations.

2. Massive underinvestment (public and private).

3. In turn, corporations are unwilling to provide quality employment – and so non-regular employment is rising as a proportion of total employment.

4. This leads to low wages growth and suppressed consumption expenditure.

5. And so it continues.

Japan needs a large fiscal shock to break this cycle and turn it into a virtuous cycle where firms are not reluctant to invest, and, in turn, are willing to offer quality employment and pay higher wages.

Until that happens, the stagnation will continue.

I would advocate, in this regard, an injection of around 45-50 trillion yen achieved by a combination of new infrastructure spending and the abandonment of the sales tax.

The first step is to demonstrate to the private sector that the government is serious about stimulating growth and will support the process fully, rather than adopting stimulus, then bowing to the fiscal surplus fanatics and trying to cut the deficit again.

That is what happened, for example, in 1997 and the result was a sales tax increase to ‘fix’ the fiscal position driving the economy into recession after fiscal policy had supported steady growth.

The aim of that first step would be not only to expand output but also to switch the non-government outlook from pessimism and gloom to optimism.

Only then will corporations start spending their massive pool of retained profits on new investment projects.

At that point the doom cycle ends and the economy can continue to expand on the back of non-government spending growth without the same level of government support.

Conclusion

The latest Japanese National Accounts data is ample evidence that a major fiscal expansion is required.

That policy change must be seen in the context of the doom cycle of secular stagnation that Japan has found itself locked into.

A major fiscal shock is required.

There can be no fiscal crisis in Japan, which means trying to achieve an erroneous trade-off between expansion and minimising the shift in the deficit, will always lead to an expansion that is too small.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill – in case you missed this

You get cited quite liberally

‘MMT, Marxism and Crisis,’ Owen Bennett, Arena, Oct 2025

https://arena.org.au/mmt-marxism-and-crisis/

Japan could be the first domino in the fall of Western Power !

Japan has become an early warning signal for the decline of the Western order. an economy in trouble a mirror reflecting the future of the United States and Europe in an era of intensifying power competition between America and China. Critical factors such as demographic decline, financial instability, security dependence, supply chain disruption, and the rise of China’s geoeconomic influence.

After 1991 the United States believed it had engineered a world in which its allies could prioritize efficiency over resilience. Japan embraced this logic wholeheartedly. It outsourced supply chains, depended heavily on foreign markets, and anchored its security to Washington’s strategic freedom.

This arrangement worked as long as global trade remained frictionless, and the American order holds together.

External forces are now overwhelming its traditional buffers.