In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s

In the previous instalment of this series of blogs I am writing, which will form the input to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state, which I am working on with Italian journalist Thomas Fazi, I covered the role of trade unions in a capitalist system where class conflict is a major dynamic. One of the characteristics of the post-modern Left is the denial of the role trade unions play in inflationary episodes. However, once we accept that the unions are creatures of capitalism and embody of the conflictual nature of income distribution within that mode of production, then it is clear that as a countervailing force against capital, unions can precipitate economic crisis if they are ‘too successful’. Too successful in this context refers to the use of their power to control the supply of labour which negative impacts on the rate of profit earned by capital and leads to a decline in investment and a rise in unemployment. Trade unions are a problem for capital. Today, we consider the way in which this ‘problem’ manifested in the inflation in Britain in the early to mid-1970s and the failure by the British Labour Party to fully understand the causation involved. By the mid-1970s, the British Labour government had surrendered to the growing dominance of the Monetarist school of thought, which diverted its gaze from the true nature of the economic crisis. They unnecessarily called in the IMF as a result of this blindness.

The inflation of the early 1970s

The long post World War 2 boom was coming to an end by end of the 1960s. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971 marked the end of the fixed exchange rate system for most nations and the tensions that had built up in the 1960s over distributional matters intensified.

The trade unions were gaining strength and becoming more militant as they sought to improve the material conditions of their membership. Membership was high and the later shifts in industry composition towards services and labour force composition towards increased female participation had not yet eroded their capacity to recruit new entrants.

The unions were just behaving according to their institutional logic as part of the conflictual class relations in Capitalism.

On the other side, the growing concentration of industry and the rise of the big multi-national firms had entrenched capital’s power more tightly.

We also need to bear in mind that British capital had neglected so-called ‘British capitalism’ and sought returns in investments abroad, which had undermined productivity growth in Britain and intensified the battle over income shares between wages and profits.

The upshot of this rising institutional power and organisation on both sides of the labour bargain was that workers were increasingly able to push for better pay and firms were increasingly able to push for higher profit margins – and each could resist the attempts of the other to improve their relative position at the expense of the other.

The role of the State in this period of post World War 2 development is also important to understand. While most governments were clearly committed to maintaining full employment through the use of their fiscal capacities, they also didn’t want unseemly breakouts of industrial unrest.

In that context, governments were also willing to deliberately use inflation to mediate between capital and labour and prevent damaging periods of industrial unrest.

As Robert Rowthorn notes (1980: 139):

[governments] … have been unable or unwilling to intervene on a scale sufficient to resolve the basic contradictions of capitalist development, and yet they have been unwilling to face the consequences of potentially very serious crisis. Where imbalances have arisen which threatened to squeeze profits and provoke a crisis, governments have used their control over expenditure to maintain demand. This has created relatively buoyant demand conditions and allowed firms to raise prices, and thereby maintain or even increase the rate of profit …

As a rule, demand is not been maintained specifically to allow firms to increase their prices, but in response to some other pressures, such as the need to maintain full employment or provide cheap finance for industry. On the other hand, when firms have made use of favourable demand conditions in order to raise their prices, governments have not usually prevented them from doing so …

So, it is clearly being governed policy to allow higher prices, and to this extent we can say that inflation is deliberate policy designed to foster the accumulation of capital by maintaining or even raising the rate of profit (emphasis in original).

John Cornwall (1989: 100) used the term “inflationary bias” to describe the situation where the real income resistance on both sides of the labour market had created the conditions where “no successful incomes policy can be implemented that would allow involuntary unemployment to be reduced to a minimum without the strong demand conditions leading to accelerating rates of inflation”.

He considered this ‘bias’ forced governments to introduce aggregate spending policies “that are restrictive enough to generate high rates of unemployment” (p.100). We will come back to that discussion presently.

[Reference: Cornwall, J. (1989) ‘Inflation as a Cause of Economic Stagnation: A Dual Model’, in Kregel, J.A. (ed.) Inflation and Income Distribution in Capitalist Crisis, London, Palgrave, Macmillan, 99-122.]

In a similar vein, Pat Devine argued in 1974 that inflation was a structural construct of Capitalism. He argued that the increased bargaining power of workers (that accompanied the long period of full employment in the Post Second World War period) and the declining productivity in the early 1970s imparted a structural bias towards inflation which manifested in the inflation breakout in the mid-1970s which he says “ended the golden age”.

This argument implicated Keynesian-style approaches to full employment by suggesting that the emphasis on high employment and high rates of growth provided the conditions for these biases to emerge. Then with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of convertible currencies and fixed exchange rates (which provided deflationary forces to economies that had strongly domestic demand growth) these structural biases came to the fore.

[Reference: Devine, P. (1974) ‘Inflation and Marxist Theory’, Marxism Today, March, 70-92.]

Robert Rowthorn (1980) argued that that the mid-1970s crisis – which marked the end of the Keynesian period and the start of the neo-liberal period – was associated with a rising inflation but also an on-going profit squeeze due to declining productivity and increasing external competition for market share. The profit squeeze led to firms reducing their rate of investment (which reduced aggregate demand growth) which combined with harsh contractions in monetary and fiscal policy created the stagflation that bedeviled the world in the second half of the 1970s.

As we have seen, Edward Heath’s resolution to this ‘structural bias” was the policy-motivated attack on the working class bargaining power – both in the form of the persistently high unemployment and specific labour relations legislation. The subsequent redistribution of real income towards profits reduced the inflation spiral as workers were unable to pursue real wages growth and productivity growth outstripped real wages growth. We will return to that issue presently.

Within this context though, inflationary pressures were rising throughout the advanced world in the late 1960s and early 1970s. There were many reasons, including the US spending effort associated with the prosecution of the Vietnam War. We do not need to discuss the plethora of events that were triggering the wage-price dynamics associated with this inflation bias.

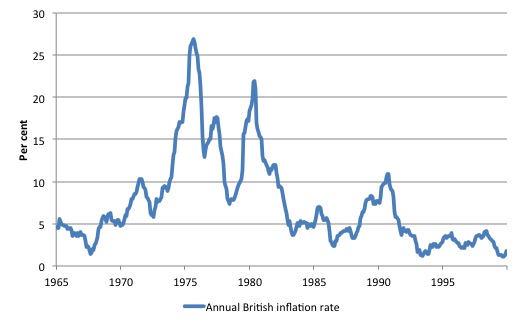

Inflation was rising in Britain in the early 1970s. The following graph shows the annual inflation rate (retail price index) from January 1965 to December 1989. The inflation in the mid-1970s that followed the oil price rises dwarfed the experience in the early 1970s.

The inflation that Edward Heath oversaw was initially instigated by the relaxed credit conditions under the Bank of England’s Competition and Credit Control (CCC), which was introduced in 1971 as part of the first wave of ‘Monetarist’-style changes in the Bank’s thinking. It freed up credit (as part of the growing free market mantra) and attempted to control the money supply via quantity targets.

The policy failed and was abandoned in 1974 but the rising inflation sparked off major industrial conflict as the two ‘price setting’ powers, the firms and the unions attempted to protect their real incomes from the rising inflation.

The Monetarists basically interpreted the inflation in traditional terms – that excessive spending was pulling up prices (the so-called ‘demand-pull inflation’ approach that was shared by Keynesians).

The Monetarists added a new focus on the role of the central bank and the money supply in creating the excess spending.

They used the term spawned by Milton Friedman (1970) – “Inflation is always and everywhere monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output” – which during the Keynesian period had been expressed as too much money chasing too few goods”.

[Reference: Friedman, M. (1970) ‘The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory’, First Wincott Memorial Lecture, University of London, September 16, 1970.]

The argument was simple – if we assume that output is already at its potential level (maximum) and velocity of circulation of the existing money stock (how many times it turns over per period) is constant, then an increasing money supply can only push prices up.

The most important part of the story though is that they argued that the money supply was directly controlled by the central bank and so if the money supply was ‘excessive’ – that is, by the logic of the theory – if there was inflation – then it must be the fault of the central bank.

Please read my blog – Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism – to understand why the Monetarist explanation of inflation was deeply flawed.

Understanding the inflation of the early 1970s requires us to reject the Monetarist causality and instead recognise that inflation can arise from supply side (cost) factors even when their is significant unemployment (output well below its potential).

As John Cornwall noted (1983: 17):

… inflation is essentially a cost-push phenomena, sustained and driven by wage-wage and wage-price mechanisms. Both of these mechanisms are seen to be the outgrowth of institutional changes that have been evolving for some time. In particular, it is argued that the development of powerful unions and oligopolies operating in a full employment context have altered the nature of the inflationary process greatly since the days before unions, but remarkably so ever since the beginnings of the postwar period.

[Reference: Cornwall, J. (1983) The Conditions for Economic Recovery, Oxford, Martin Robertson.]

Cornwall also added a political element to this observation.

He argued that (1983: 17):

Many societies will not tolerate continuous, high unemployment and sooner or later the money supply and aggregate demand targets will be adjusted to stabilise unemployment … Strong trade unions generate strong political as well is market power. If unemployment rates cannot be allowed to rise without limit for political reasons, then whatever inflation is still left when the constraint is reached must be validated.

The notion of cost-push inflation (sometimes called ‘sellers inflation’) has a long tradition in the progressive literature (Marx, Kalecki, Lerner, Kaldor, Weintraub) although it is not exclusively a progressive theory.

Milton Friedman also considered that wage demands from trade unions were a major threat to inflation although he ultimately considered central bank monetary policy to be the real problem in that they accommodated these wage demands by increasing the money supply.

Cost-push inflation is an easy concept to understand and is generally explained in the context of ‘product markets’ (where goods and services are sold) where firms have price setting power. In the real world, firms set prices by applying some form of profit mark-up to costs.

While specific arrangements might vary, firms are considered to desire target profit rates which they render operational by the mark-up on unit costs. Unit costs are driven largely by wage costs, productivity movements and raw material prices.

Trade union bargaining power was considered an important component of the capacity of workers to realise nominal wage gains and this power was considered to be pro-cyclical – that is, when the economy is operating at “high pressure” (high levels of capacity utilisation) workers are more able to succeed in gaining money wage gains.

In these models, unemployment is seen as disciplining the capacity of workers to gain wages growth – in line with Karl Marx’s reserve army of unemployed idea.

Workers have various motivations depending on the theory but most accept that real wages growth (increasing the capacity of the nominal or money wage to command real goods and services) is a primary aim of most wage bargaining.

So income distribution in capitalism can be characterised as a ‘battle of the mark-ups’ – workers try to get more real output for themselves by pushing for higher money wages and firms then resisting the squeeze on their profits by passing on the rising cost – that is, increasing prices with the mark-up constant.

At that point there is no inflation – just a once-off rise in prices and no change to the distribution of national income in real terms.

However, if economic conditions are bouyant and the threat of unemployment is low, workers may resist the attempt by capital to keep their real wage constant (or falling) and hence they may respond to the increasing prices by making further nominal wage demands.

If their bargaining power is strong (which from the firm’s perspective is usually in terms of how much damage the workers can inflict via industrial action on output and hence profits) then they are likely to be successful.

At that point there is still no inflation. But if firms are not willing to absorb the squeeze on their real output claims then they will raise prices again and the beginnings of a wage-price spiral begins. If this process continues then cost-push inflation is observed.

Alternatively, the pressure might come from firms trying to expand their real income by increasing the mark-up at the expense of workers. The workers then engage in real wage resistance drives higher nominal wage demands in retaliation. In this case, we might refer to the unfolding inflationary process as a price-wage spiral.

Further, wage pressures might come from a particular group of workers gaining a large wage increase, which alters the relativities with other workers. To restore these relativities, which in no small way reflect social status, these workers will push for higher nominal wages. A wage-wage spiral, might then precipitate a wage-price spiral.

These insights led to the development of the so-called Conflict theory of inflation.

A series of articles in Marxism Today in 1974 advanced the notion of inflation being the result of a distributional conflict between workers and capital. One such article by Pat Devine (1974) ‘Inflation and Marxist Theory’, Marxism Today, March, 70-92 adequately summarised the approach.

The conflict theory derives directly from cost-push theories referred to above. Conflict theory recognises that the money supply is not controlled by the central bank, as in the Monetarist conception, but is, rather reflects the demand for credit by private firms and consumers through the commercial banking system.

The market power of firms and unions allows them to influences prices and wage outcomes without much correspondence to the state of the economy in search of their respective desired real output (income) shares.

In each period, the economy produces a given real output which is shared between the groups with distributional claims. If the desired real shares of the workers and capital is consistent with the available real output produced then there is no incompatibility and there will be no inflationary pressures.

But when the sum of the distributional claims (expressed in nominal terms – money wage demands and mark-ups) are greater than the real output available then inflation can occurs via the wage-price or price-wage mechanisms noted above.

The upshot is that it is the conflict over available real output, which is endemic to the class conflict withn capitalism, that promotes inflation.

Various dimensions can then be studied – the extent to which different wage contracts overlap and are adjusted, the rate of growth of productivity (which provides ‘room’ for the wage demands to be accommodated without squeezing the profit margin), the state of capacity utilisation (which disciplines the capacity of the firms to pass on increasing costs), the rate of unemployment (which disciplines the capacity of workers to push for nominal wages growth).

As noted above, the role of the state is also important. Conflict theories of inflation note that for this distributional conflict to become a full-blown inflation the central bank has to ultimately ‘accommodate’ the conflict. What does that mean?

If the central bank pushes up interest rates and makes credit more expensive, firms will be less able to pay the higher money wages (the conceptualisation is that firms access credit to fund their working capital needs in advance of realisation via sales). Production becomes more difficult and workers (in weaker bargaining positions) are laid off.

The rising unemployment, in turn, eventually discourages the workers from pursuing their on-going demand for wage increases and ultimately the inflationary process is choked off.

However, if the central bank doesn’t tighten monetary policy and the fiscal authorities do not increase taxes or cut public spending then the incompatible distributional claims will play out and inflation becomes inevitable.

Rising industrial troubles in Britain – early 1970s

With the inflation rate rising in Britain, productivity growth stagnant as a result of the decisions by capital to invest abroad and neglect investment opportunities in Britain itself, and the Tory government intent on forcing workers to reduce real incomes rather than trying to stimulate investment, it was no surprise that the inherent destructive tendencies of capitalism would come to the fore in the early 1970s.

As Rowthorn observed (1980: 143):

… during the 1950s and 1960s … British governments gave a rather low priority to domestic economic development, and devoted both resources and energies to the creation of the world role for British capitalism. This involved rebuilding the City of London as a world financial Centre, facilitating overseas investment by big industrial firms and supporting a huge military establishment. It absorbed resources which could have been used productively at home, and was accompanied by a laissez-faire fairy economic policy of non-intervention in the private sector. As a result, British industry failed to keep up with its rivals and economic development was relatively slow. Clearly, such a process of relative decline must eventually lead to severe problems and, indeed in the late 1960s Britain entered a prolonged period of crisis.

Despite the popular narratives from the Right, Rowthorn also notes that “British workers … were not very militant in this period and put up with a rather modest increase in their living standards” (p.144).

So the neglect of continuing to build the productive potential of the British economy – “a suicidal strategy” according to Rowthorn (p.144) – “was made possible by the quiescence of British workers” (p.144).

The militancy of the unions in the early 1970s, therefore, has to be seen in this historical context and the behaviour of capital in the preceding two decades.

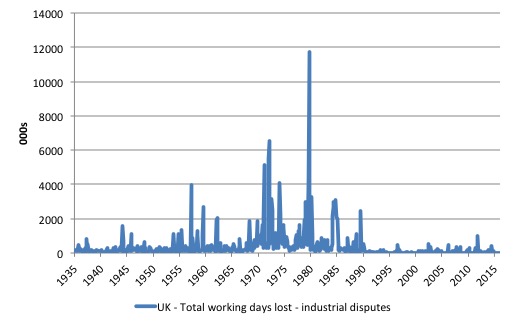

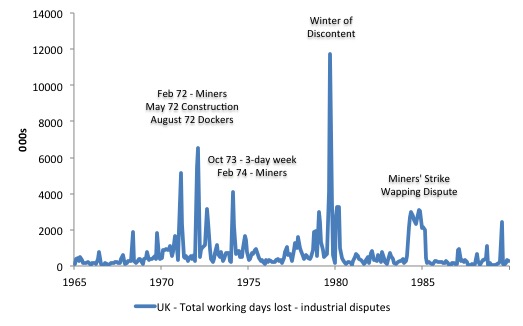

Data available from the British Office of National Statistics for – Labour disputes – indeed, shows the growing industrial relations tension in Britain in the early 1970s, followed by Thatcher’s showdown with the unions and the subsequent muting of union power in the 1990s and beyond.

The following graph shows the total work days lost per month from industrial disputes in all sectors (thousands) in Britain from January 1935 to January 2016. The early 1970s saw a rapid rise in the days lost from industrial disputes as the Heath government introduced the Industrial Relations Act 1971

A closer examination of the period January 1965 to December 1990 is provided in the next graph.

We have discussed Edward Heath’s battle with the trade unions in the early 1970s. While Heath had largely rejected the ideas of Milton Friedman with respect to macroeconomic policy, the desire to quell the power of the trade unions remained a traditional Tory battlefield.

Please read my blog – The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party – for more discussion on this point.

The Industrial Relations Act 1971 was a provocative act by the Heath government to precipitate a showdown with the unions. The Tories clearly believed that the British public were ripe for a prolonged anti-union crusade, which would shift the bargaining power firmly in favour of the Tories’ natural allies, Capital.

The outcome was less favourable for the Tories and led to their political demise in the February 1974 general election and a subsequent repeal of many of the clearly anti-worker aspects embedded in the harsh Industrial Relations Act 1971. While the unions were victorious during this period and managed to resist the real wage impingement attempted by capital and the Tory government, their ‘day in the sun’ was soon to end.

The oil crisis in late 1973 would see to that.

The OPEC oil crisis 1973 – shifts the ground further against the workers

There were two major oil price shocks in the 1970s, which produced dramatic shifts in economic environment that the government around the world had to manage. In a sense, these shocks were without precedent.

The first occurred in October 1973, which caused a surge in the British inflation rate and inflation rates around the world, particularly in oil-dependent economies.

The causation was clear.

While wage-price or price-wage spirals can emerge through shifts in the real income aspirations of either workers or capital, which then sets off resistance from the other party, raw material price shocks can also trigger of a cost-push inflation.

They can be imported or domestically-sourced.

An imported resource price rise immediately leads to a loss of real income for the nation in question. The 1974 oil price hike stirred up an already tense industrial relations environment in Britain as they did in other nations.

The question was how who would bear the real income losses for the nation as a result of the sharp rise in oil prices?

Something had to give. The loss had to be borne by the claimants on real income and the proportion in which the losses would be ‘shared’ then became an outcome of a renewed distributional struggle.

In general terms, if the workers resisted the lower real wages or if bosses did not accept that some squeeze on their profit margin was inevitable, then a wage-price/price-wage spiral would ensure.

And it did – in Britain in 1974. Workers, buoyed by their victories in 1972 and again in early 1974, resisted the real wage cuts.

British capital then retaliated with price hikes and while the Heath government oversaw the first acceleration in the inflation rate, it was the newly-elected Wilson Labour government that oversaw the rise in inflation, which peaked at 26.9 per cent in August 1975.

The government can employ a number of strategies when faced with this type of dynamic. It can maintain the existing nominal demand growth to protect employment but, in doing so, run the risk of reinforcing the spiral.

Alternatively, it can use a combination of strategies to discipline the inflation process including the tightening of fiscal and monetary policy to create unemployment; the development of consensual incomes policies and/or the imposition of wage-price guidelines (without consensus).

The Wilson government was riven with conflict on how to handle the matter and, unfortunately, adopted a Monetarist perspective and attempted to scorch the economy with austerity.

Conclusion

We are now at the point we can appreciate the importance of James Callaghan’s famous 1976 Black Speech to the Labour Party Conference and his decision to call on the IMF for help in changing the perspective of the Left on fiscal policy.

We will deal with that turning point in the next blog of this series.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

We have now published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 US dollars)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 US dollars)

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics

Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism

Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts

Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model

Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement

Chapter 10: Money and Banking

Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation

Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy

Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations

Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations

Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available the week after next.

Note: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

We need a system where the rate of return on enterprise is higher than putting money in the bank.+ A Low cost of capital and sufficiently high enough rates of profit to induce high levels of Investment and output(and employment).

To me the Marxist view: ” when the sum of distributional claims are greater than the real output available,inflation can occur”

Sounds exactly like the monetarist: “too much money chasing too few goods”

Bill

actually i have a good example of how inflation been solved (its close to the way you described how its should be done)

in israel in 1980-1985 the inflation been huge (record high in 1983 450%),there been many causes for that

1.the involvment in lebanon in the 80-s (Israeli version of vietnam war) which soaked huge amount of money for war efforts.

2.Tarif shock therapy of the neo-liberal likud party (its replaced the israeli labour party in 1977) which basically caused sharp outflow of capital and demand to abroad in a really quick timeline (well they indeed created a shock).

3.in the 70-s Israel expierenced lost decade of stagnating productivity and growth most likely the reason is

the deregulated private banking sector (which created by the vision of the so called “patinking boys” his students in heberew university in jerusalem which believed in self regulating financial sector),the deregulated banking sector started to do market manipulation with its own stocks until the face value of this small israeli banks been something like barclays or lloyds this manipulation created 2 big problems.

a.a lot of capital start to go from productive industries to this banks which did wild failed investments abroad at expense of investing in israel.

b.in 1983 the face value of this banks been so huge so they werent able to maintain the price of their stocks any longer and 6 from the 7 operating banks in israel a time collapsed because of that and had to be bailout by the government and eventually natioanlised by the government.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1983_Israel_bank_stock_crisis

but lets come back to the topic with inflation so how israel been able to reduce its inflation?

first of all israel asked help from the american government and not from the IMF (its helped a lot) also israel

still had serious progressive sentiment back then which also helped a lot.

A significant cut in government expenditures and deficit and increased taxation (even though no austerity or surplus budgets at all).

Reaching an agreement with the then-powerful Histadrut (histardut combined all labour unions of israel at the time into one powerful organization) labor union to enact wage controls, thus decoupling rampant wage from price inflation.

Emergency measures imposing temporary price controls over a broad range of basic products and services .

A sharp devaluation of the Shekel, followed by a policy of a long-term fixed foreign exchange rate.(bad neo liberal policy there been even a more horrible plan to dollarize the economy completely)

Curbing the Bank of Israel’s ability to print money to cover government deficits.(useless neo liberal policy in our MMT world the bank of israel like the fed can buy government bonds on the secondery market anyway).

creating a new currency the new israeli shekel which value is 1000 old israeli shekels.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1985_Israel_Economic_Stabilization_Plan

the interesting case here is that israel fought the inflation with higher taxation and strict price controls combined with freezing the salary of the labour unions for an amount of time and its been way better than what happened in the UK.

even though the inflation recorded at 450 percent in israel not at 26 percent so its gave to israel free hand to do something out of mainstream neo liberal failed tool arsenal.

This post really highlights the role that competition in an economy is supposed to play, but really doesn’t manage to accomplish. That firms would be able to set price based on a markup over costs would show that competition as described in standard econ theory really doesn’t exist. And I would argue that that is where the crux of the inflation problem lies. If you were to eliminate that ability to price then inflation goes away.

I would argue that a good labor union is at all times seeking to remove the price of labor from competition between firms across that industry. While unions seek to limit competition in that sense, firms are still able to compete based on labor management, technology and productivity, organization, marketing and sales technique, and costs of other inputs besides labor. Yes, I realize that unions will also seek to limit some labor management techniques that firms like to employ, but these limitations still leave room for effective competitive management if they are instituted across an industry, or better yet throughout the country through labor law.

Overall, I am very impressed with this series so far. There has been nothing “Torylike?” about it that I can see. I am very interested in how the Job Guarantee program would work to limit price-wage or wage-wage-price inflation though. Not that it would have to do better at it than the present system to still be an effective program worth doing.

During one of the unions’ confrontations with the government while Joe Gormley was head of the NUM, the miners asked for wage rises along with other “demands” such as better working conditions, better pensions, and the like. At the last minute, after a weekend, as I recall, the government had set out in a white paper which stated that they were prepared to acede to union demands for those changes that did not necessitate immediate injections of finance, though they did not put their point that way.

If memory serves, the evening before the government published the white paper, I remember Gormley holding a press conference saying that the union was prepared to give way on the demand for higher wages if the government would give way on all the other demands, none of which would cost the government anything immediately, exactly what was in the white paper, though the paper had not yet been made public. The government was caught in a trap of its own making. Gormley had outwitted them — some of us interpreted the event in this way. Not long afterwards, unfortunately, he retired, to be replaced by Scargill. I can’t, however, remember which miners’ dispute it was when this event took place.

It was to be the last time the miners ever won a dispute of any significance with the government of the day. It didn’t take long after that for the NUM to be neutered and the miners decimated. The Thatcher government claimed that the miners and their union were “the enemy within”, a topic subjected to scathing analyis by Seamus Milne.

Addendum: Even if you believed, as many did, that the mines had to be be closed down, not many believed that there was any excuse, other than to punish the miners and to use them as an example to the other unions, none of which were as powerful as they were, for Thatcher to treat the mining communities the way Thatcher did. It was pure vindictiveness. A number of them have still not completely recovered.

It is not unlike the manner in which Osborne is treating the disabled, with even less justification. Disgraceful.

Hi Bill,

There is an interesting comment on your posting here:

http://mikenormaneconomics.blogspot.com/2016/04/bill-mitchell-distributional-conflict.html?showComment=1460083328583#c2460160698385975233

I’m inclined to agree with the proposition that the 70s inflation was from a rising oil price

(the USA lost monopoly price control). Warren Mosler has made the same point (though he

gave different reasons).

I’d be very interested in any response you might have to Dan Lynch’s comment over there.

Cheers,

Tofu

Dear TofuNFiatRGood4U (at 2016/04/08 at 15:22)

Thanks for the link to Mike’s post and the comment.

Any commentator who starts of with “Nonsense!” better be on sound ground given the lack of qualification of such an emphatic entry.

The problem is that the commentator both doesn’t know the historical facts nor appears to understand the dynamics of an inflationary process in a capitalist, monetary economy.

I wonder whether he has actually read the 23 part series that I have produced to date. I doubt it.

1. My blog in question was entitled “Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s” and the empirical analysis was about Britain in that period, although the dynamics I discuss were applicable everywhere.

2. One who is familiar with the historical facts will readily know that inflation in Britain and other nations (such as the US) was already rising significantly in the late 1960s.

Check the graph out that is presented in the blog. In the UK, inflation rose from 1.5 per cent per annum in the November 1967 to 5.2 per cent a year later. By August 1971 it was peaking at 10.3 per cent.

It then moderated a little before accelerating again after the oil shock in October 1973.

Similarly, the US inflation rate average 2.78 per cent through 1967 and then rose to 4.27 per cent in 1968, 5.46 per cent in 1969, 5.84 per cent in 1970, and was up to 7.4 per cent in the month before the OPEC oil price shock was introduced.

However, you want to spin the story, the crude oil price was flat (at around $US20 per barrel) until the acceleration began in the October 1973 and it then jumped to $US49 per barrel by March 1974.

It is simply incorrect and a denial of the historical facts to blame OPEC for the inflation prior to late 1973.

3. I have written many paragraphs in articles, book chapters, blogs, Op Ed pieces and in several of my books analysing the impact of the OPEC oil price shock. To write a comment attacking my blog as if I had ignored that event is disengenous and suggest the commentator has read none of my work over many years on that topic.

But moreover and importantly, the blog in question provides a detailed account of how inflation begins and sustains itself through a adjustment response mechanism.

It is important to understand that a single event cannot lead to inflation. An inflationary process is an outcome of a series of events and responses, especially when it is coming from the supply-side (a raw material price shock).

The OPEC oil price rise in October 1973 was a trigger but alone could not have caused the rapid escalation in prices around the world. To think otherwise is to misunderstand the dynamic interactions that arise in the distributional mechanism of a capitalist, monetary system.

If capital and labour had have agreed (tacitly or otherwise) to swallow the imported oil price shock – and that would mean they would have to have accepted the real income loss that the rising oil prices generated – then there would have been no inflation.

A once-off price rise is not inflation.

So imagine that capital accepted it would wear the real income loss totally and absorbed the cost rise in their margins. No inflation would occur.

Imagine that capital would not accept the real income loss and pushed up prices to maintain their margin. A once-off price level increase would have occurred.

Now, whether that becomes an inflationary spiral depends on the response of the workers. If they accepted the real wage cut – then that is the end of it. They are worse off and the economy digests the real income loss. OPEC exporters gain, workers lose.

However, if they resist the real wage cut and they push for higher nominal wages to compensation for the higher prices then the wage-price spiral is starting.

If firms, in turn, resist the margin squeeze and pass on the nominal wage increases as higher prices – then we have an inflationary process.

It is simple ignorance to think that a single event – a raw material price rise, or a successful wage demand or a successful profit margin push – will generate inflation.

Whether these events result in inflation depends on the responses of the distributional claimants and the response of government to the distributional conflict.

I hope that explanation helps you understand this complex area of economics better.

The commentator on Mike’s site has just revealed his ignorance.

best wishes

bill

And here we have another version of the usual neoliberal story of the completely imaginary “wage-price” spiral of the 70s and 80s, according to which nasty greedy workers pushed up their wages and this caused endogenous price inflation.

The story that is instead apparent from the numbers of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s is that the great inflation was the product of huge government “global security” oriented spending in the USA, and other factors that caused the USA to switch from a net exporter to a net importer, and the international dollar shortage of the 1940s and 1950s to become slowly a dollar glut, which resulted not many years later in the decision to devalue the dollar by a huge amount, the *symptom* of which was the end of the gold standard.

The huge devaluation of the dollar was in effect a “cram-down”. The oil producers refused to be crammed down and increased massively the price of their product after the dollar devaluation, and the Fed Board decided to “accomodate” the huge exogenous price shock, to avoid undermining the USA government’s global security policy.

All this transmitted the cram-down shock wave through the value chain, and unionized workers reacted to sharply rising prices driven by oil and commodity inflation by demanding higher wages, which was temporarily successful. At that point because of the exogenous price shock caused by the falling dollar and oil and commodity producers and unionized workers resisting the cram-down it was creditors and businesses who were forced to take the cram-down as massive losses on existing bond valuation because of increasing nominal interest rates and much reduced profits.

Eventually creditors and businesses fought back and thanks to Volcker and Reagan managed to push the costs of the cram-down onto unionized and non-unionized workers, and debtors, and the cram-down continues today: in the USA median hourly wages have been flat or declining since 1973, and the interest rates have been falling for decades, generating enormous capital gains for creditors.

Most other anglo-american economies just followed the leader, in various particular ways, and most of the world economy was deeply affected.

It was a gigantic price-push shock caused by USA government dollar policy, not by greedy unions causing wage-push price increases.

BTW to show how gigantic the changes were in the 1960s an interesting quote by V Bonham-Carter diary dated May 14th 1963:

“[President Kennedy] went on to describe how [de Gaulle] was now blocking all progress in Europe- in defence, economic, etc. I asked him how he thought this road-block could be broken. He said, ‘The root of the matter is that not only you in Britain but we in the USA have now become debtors and not, as we always used to be, creditors. The gold reserve has ebbed at the following rate (he then gave the figures for the last few years).”

The big change had been happening for a while, the other symptom was that in 1961 many IMF “title XIV” (not quite convertible currency) members had become “title VIII” (convertible currency) members, obviously because their trade situation had much improved thanks to the switch from dollar shortage to dollar glut:

The link is old but I am sure readers of comments will be able to find this

http://www.mocavo.com/Department-of-State-Bulletin-Volume-Xliv-2/316430/402

“Ten members of the International Monetary Fund today [February 15] announced the formal convertibility of their currencies within the meaning of the articles of agreement of the Fund. The 10 are the United Kingdom, the 6 members of the European Economic Community-that is, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands-together with Sweden, Ireland, and Peru. These actions are heartily welcomed by the United States. They represent the culmination of the efforts of the 10 countries to achieve one of the major objectives set forth in the Fund articles. They constitute further evidence that the system of monetary cooperation embodied in the Fund is working successfully. Most of these countries announced the convertibility of their currencies for nonresidents some 2 years ago.”

That was basically what eventually destroyed the Bretton Woods system for which the IMF had been created, so the last bit of the quote is quite ironic.

Dear Bob (at 2016/04/08 at 21:40)

You said in Pavlovian fashion:

You obviously didn’t appreciate the nuances of the blog and the discussion therein. There was no mention of “nasty greedy workers” nor any inference to that end.

Note in your story real wage resistance by workers was an essential part in the inflation causal chain. Not much different to my story really.

best wishes

bill

And I thought supply and demand produced the right price .

Conflict is inevitable amongst capital and labour as well as between capital and labour.

The government can mitigate conflict via taxation,spending and regulation but economists

dreams of wage policies ,price policies ,buffer stocks , money supply control to SOLVE

inflation are utopian hubris.

Despite the trade union militancy and the preceding full employment policies of the post

war settlement it is worth pointing out that poverty was still very real by the mid 70’s

and not just in the USA I can testify to poverty in the uk being raised in a large family

renting a slum,relying on free school meals and never going on family vacations.

Yes my father did not benefit from strong trade unions in his line of work..

Very much part of the appeal of negative rates of taxation amongst lower earners or

a frame changing universal OMF citizens wage is that it does not contribute to cost

push inflation .Raising the levels of non waged income would be another mitigating

tool for government to use confronted by a ubiquitous price rise like energy.

Capatalsm like feudalism and slavery before it has never eliminated poverty even

when it has reached full employment and had powerful unionism .

Good governance can mitigate conflict and undermine trade union militancy but

there is no magic bullet.

Bill,

Thanks for your response. I have a few follow-up/clarification questions–would understand if you don’t have time or can only provide a link:

Is it correct to say that you are describing cost-push inflation (from the mid 1960’s until 1980ish)?

Is there an example of demand-pull inflation (maybe the German hyper-inflation of 1922-23?)

I once read (sorry, forgot the source) that the last instance of US demand-pull inflation occurred in 1921, when the FED pushed too much money into the post WWI economy.

I have the impression that demand-pull inflation is more of an irritant: if everyone keeps up, there is no decline in anyone’s standard of living (whereas cost-push inflation represents real resources becoming scarcer)–is this a reasonable characterization between the two types?

Thanks again for your response.

Quote: “Bob says:

Friday, April 8, 2016 at 21:44

BTW to show how gigantic the changes were in the 1960s an interesting quote by V Bonham-Carter diary dated May 14th 1963:”

.

To add a little historical perspective to this, that would be Lady Violet Bonham-Carter, daughter of the one-time Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, and later a politician in her own right, and eminently well-connected. No surprise that she would be on hob-nobbing terms with world leaders like JFK. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violet_Bonham_Carter

.

Regarding the “Oil Shock”: I am wondering what if there was anything additional an MMT-aware UK government might have done to minimise it. I’m thinking perhaps of something like running a bigger deficit and using it to directly subsidise consumers (domestic and industrial) of oil products, or at least to drastically reduce or remove duties/taxes on oil / oil products. Or would this have simply led to more inflation?

.

Adding to Kevin Harding’s comment about poverty in the UK in the 1970s, I am reminded of the famous 1966 TV drama “Cathy Come Home”, which brought to light problems of poverty, unemployment and homelessness, among a UK that generally at that time was regarded (and felt – I remember that feeling) as becoming slowly but steadily more prosperous.