In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality

This is a further instalment in tracing through the British currency crisis in 1976 and its retreat to the IMF later in that year. Today we discuss whether it was the IMF that forced the change of direction for British Labour or all their own dirty work with the IMF just being used to depoliticise what Callaghan and Healey wanted to do (and were doing) anyway. We trace through the way the leadership of the British Labour government were building the case for austerity and the path they followed leading up to the request to the IMF for a stand-by loan. Far from being the only alternative available, the course taken by the Government was a triumph of ideology and perception over evidence and reality.

After the large credit line was provided by the Bank of International Settlements in June 1976, the Chancellor announced further cuts in government spending in July and the formal introduction of a money supply growth target, designed to obviate the perceived need to approach the IMF for a loan (Capie, 2010: 751)

[Reference: Capie, F. (2010) The Bank of England: 1950s to 1979, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.]

For a short period, the currency markets were quiet. The currency turbulence resumed in September because as Douglas Wass noted so-called “market confidence” (Wass, 2008: 223) in the pound remained low. Douglas Wass was the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury at the time.

The Bank of England had also injected more than $US800 million into the foreign exchange markets during July and August to bolster the pound, which appeared to stabilise the parity for a time (Wass, 2008).

However, locked into the mindset of defending the parity, it was clear that the Bank’s foreign reserves would be depleted given the expected official intervention requirements in the coming months and the Government’s need to repay the swap loans that were due on December 7, 1976.

Constrained by its ideological predilection against any form of capital or import controls, an aversion to depreciation, and a fear that using central bank funds to match the fiscal deficit would cause inflation, the British Treasury formed the view that the nation was in a “blind alley” (Wass, 2008: 223) unless it approached the IMF for funding.

Even though the currency was now floating, the hangovers from the Bretton Woods system, and the conflation of the level of the pound with some patriotic symbol of British greatness, were as strong as ever. Peter Browning, who was the Treasury’s chief media officer at the time, later wrote that (1986: 5) that “open advocacy of devaluation was … the next worse thing to publishing obscene literature”.

He was referring to the Wilson Government’s first period of office in the 1960s under the Bretton Woods system where the deep reluctance to formally devalue the obviously overvalued pound was a major feature of the travails he encountered in that period of office.

But the same cultural aversion to allowing the pound to adjust downwards in times of overvaluation persisted into the floating exchange period, even though the ‘market’ would have sorted out the value rather than entering a process where the government had to seek permission from the IMF to adjust the parity as was the case under the Bretton Woods arrangements.

[Reference: Browning, P. (1986) The Treasury and economic policy, 1964-1985, London, Longman.]

So the decision to approach the IMF for a stand-by loan, to resist depreciation and the need to impose restrictive capital and trade measures, was only a matter of when rather than if! Wass (2008: 223) wrote “The only question in the mind of the Treasury was that of timing”.

Healey had also told his colleagues in a briefing on his special July spending cuts that (British Cabinet, 1976m: 3):

It will … be difficult to finance a large PSBR except by driving interest rates to levels at which industry cannot afford to borrow, thus choking off the investment on which sustained growth will depend and without which there is no hope of reducing unemployment to acceptable levels …

The only alternative would be to print money …. with consequences for inflation … If no action were taken to rein back the growth of money we would create an excess of liquidity which would add to our difficulties.

[Reference: British Cabinet (1976m) Public Expenditure 1977-78 – The Economic Background, July 2, 1976, CP(76) 42, TNA CAB/129/190/17.]

This was straight out of the mainstream textbooks at the time and reflected an increasingly Monetarist perspective. It was hard to see how firms would not respond to the increased demand by employing more workers given that British unemployment was at elevated levels at the time.

The fact that the Treasury had narrowed their focus and considered the IMF to be the only alternative went to the heart of the question: How much policy independence does a currency-issuing state have in the context of global capital mobility?

It is significant that the austerity mentality that prevailed within the economic areas of the British government at the time and enunciated by the Chancellor Denis Healey were not forced on Britain by the IMF negotiations.

In fact, the evidence clearly demonstrates that British Labour were the first government in advanced nations to break with the Keynesian consensus at the time (we exclude Germany as a special Ordoliberal case, although they resorted to Keynesian remedies in the late 1960s).

The IMF adopted a typical stance in the negotiations with the British government, which by then was emerging as neo-liberal in flavour.

The fact is that the Labour Party had already began to adopt an austerity approach in 1974 (Rogers, 2009; Ludlum, 1992).

Ludlum (1992) notes that Chancellor Healey had already made substantial spending cuts in the “April 1975 Budget” (p.717), following repeated warnings to his colleagues that he would do so. Then, the February 1976 Public Expenditure White Paper “announced a total of £4.6 billion of planned cuts” (p.717) and was followed in July 1976 “by an emergency package of a further £1 billion cut in planned spending in 1977-78” as well as some tax hikes (p.717).

[Reference: Ludlum, S. (1992) ‘The Gnomes of Washington: Four Myths of the 1976 IMF Crisis’, Political Studies, 40 (4), 713-727.]

When Healey announced the approach to the IMF on September 29, 1976 at the Labour Party Conference he said that (Ludlum, 1992: 717:

I’m going to negotiate with the IMF, on the bais of our existing policies, not changes in policies …

Here is the snippet of Healey’s speech to the Blackpool Annual Conference where he announces that the British government would ask the IMF for a standy-by loan:

Ludlum (1992: 720) also notes that Healey signalled his intention to impose cash limits on public spending programs in the April ‘Budget’ 1975 and then published the details in his emergency July 1975 statement. In 1977-78, these limits contributed to a public “underspend … more than twice as large as the additional cuts required for that by year by the IMF deal” (p. 720).

Finally, far from bowing to conditions imposed by a Monetarist-infested IMF in return for the stand-by loan, Healey already “announced an unambiguous commitment to limiting M3 money supply growth in the Budget of April 1976 and had published an M3 money supply forecast, set at 12 per cent, in the July 1976 measures” (p.721).

Ludlum also argues convincingly that (p.724):

The most famous piece of evidence offered for Labour’s shift away from Keynesian employment policies towards the monetarist ‘natural rate hypothesis’ has been Callaghan’s address to the Party Conference in September 1976 before the IMF application. In this speech, he explicitly recanted Keynesian full employment techniques and equally explicitly introduced the monetarist natural rate of unemployment hypothesis as an ‘absolute fact of life’.” The speech is said to have ‘effectively sounded the death-knell for postwar Keynesian policies’, and to have ‘served the monetarist cause for years to come’. The evidence suggests, however, that the shift away from the post-war consensus on sustaining fuli employment through demand management had begun a full two years before Callaghan’s proclamation of the death of Keynesianism. Whiteley has argued that the incoming government’s very first Budget was mildly deflationary at a time when unemployment was already at 2.5 per cent.

It was clear that the Wilson then Callaghan government were prepared to allow unemployment to rise as it began to preach a Monetarist-style ‘inflation-first’ dogma well before it determined that the IMF was the only alternative to getting funds.

That articulation did not first appear in Callaghan’s speech at the Annual Labour Conference in Blackpool on September 28, 1976 even though the words he used there (see below) have been repeated over and over again, ad nauseum by Leftists who claim the nation state is dead as a result of the forces of globalisation.

In fact, Callaghan made a decisive speech to the House of Commons on June 9, 1976 where he articulated much of what he would repeat in Blackpool some three months later.

In reply to a speech by the then Member for Finchley, Margaret Thatcher to support a ‘no confidence’ motion she was moving against the government, Callaghan said clearly (HC Deb 09 June 1976 vol 912 cc 1458-1459:

The Government’s economic objective is to overcome inflation … That is the Government’s first and overriding objective … Our second objective is to make inroads into the unacceptably high level of unemployment …

It is significant he didn’t include the objective of full employment, which by then had been abandoned as a commitment by the British Labour Party (Ludlum, 1992).

The ‘Budget’ strategy outlined by Healey over several years clearly recognised that unemployment would rise as it cut public spending, which was after all, one of the key reasons why the Left were so opposed to the February 1976 Public Expenditure White Paper and any talk of negotiating further austerity with the IMF.

In the July 10, 1975 – Draft White Paper on Inflation – which emerged out of negotiations between the Government, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) and the Trades Union Congress (TUC), it was stated that:

Inflation is the most serious economic problem facing the country.

[Reference: British Cabinet (1975) Draft White Paper on Inflation, C(75) 76, TNA cab-128-57-cc-75-33.]

This is despite the fact that official unemployment was already above 1.2 million (and under the policies adopted would peak above 1.5 million).

It was also clear that the inflation that had been triggered by the OPEC oil shocks and the distributional struggle between labour and capital that followed to determine who would take the real losses implied by the higher import prices was abating, especially given the co-operation that the trade unions had provided under the Social Contract.

The acceptance of the Monetarist mainstream views which ultimately led to Callaghan embracing the TINA-IMF type narrative was thus already starting to dominate senior Labour party politicians long before the IMF came into the picture.

In 1975, the Government’s official lines was that the persistently high inflation and current account deficits were being caused by what it considered to be an unsustainable fiscal deficit, which was driving excessive monetary growth. This was fairly classic Monetarist causation.

They nuanced the argument with the crowding out notions advanced at the time by the Bacon-Eltis thesis (see The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976).

One commentator, J.S. Fforde (1983: 203), who was an advisor to the Bank of England Governor at the time, claimed that Healey’s introduction of a published M3 growth target in 1976 was necessary because it “became clear that financial confidence was unlikely to be obtained without it”.

[Reference: Fforde, J.K. (1983) ‘Setting Monetary Objectives’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, June – LINK]

But while this was a Monetarist-inspired intervention, Fforde claims that “other aspects of policy, which continued to be conducted broadly along Keynesian lines” (p.203). He termed this policy approach “monetarily-constrained ‘Keynesianism'” (p.204), which gave way to “monetarism” in 1979 under Margaret Thatcher.

In other words, the British Labour government in this period was caught betwixt two competing macroeconomic paradigms – which also made the framing of policy incoherent at times (for example, fiscal austerity and interest rates of 15 per cent when unemployment was rising beyond 1.4 million).

It also brought different factions of Cabinet into conflict.

Interestingly and as an aside to our argument, Fforde also offered this advice to his readership (p.200):

The United Kingdom is a unitary state and a parliamentary democracy. Subject to parliamentary and ultimately electoral approval, macroeconomic policy is decided and carried out by a uni ed executive branch. This includes, for purposes of this paper, both the Treasury and the Bank of England. The latter is institutionally and operationally separate from the Treasury but is best regarded as the central banking arm of a centralised macroeconomic executive.

Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank – for more discussion on this point from an Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective.

While Denis Healey had fallen for the argument that fiscal austerity and monetary control was necessary, the Left of the party were developing alternatives.

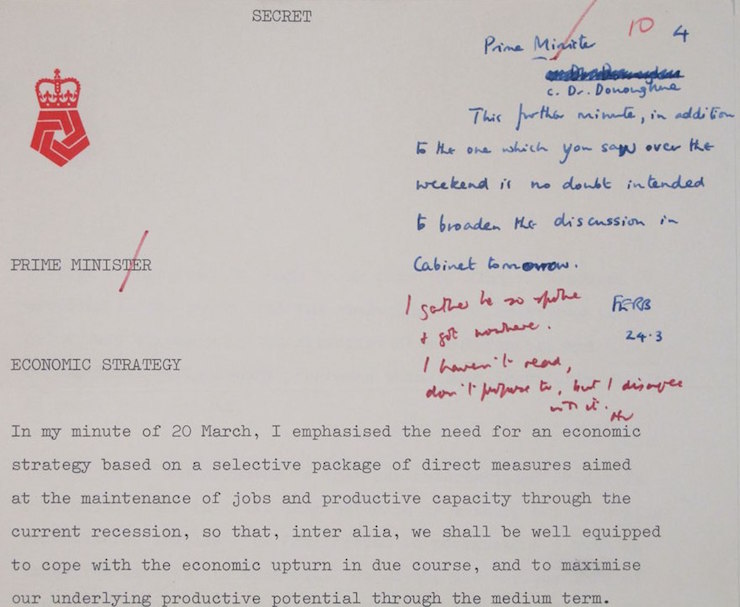

On March 24, 1975, Tony Benn then the Secretary of State for Industry, sent the Prime Minister with a document outlining the alternative path, which was based on such policy changes as import controls (particularly on luxury items), and a national plan to invest in and revitalise British industry.

Wilson annotated the document in this way:

I haven’t read, don’t propose to, but I disagree with it.

The following graphic is an image of the front page of the document held in the British Archives (TNA PREM 16/341). Wilson’s annotation is the red handwritten note at the top right hand side.

That is one of the characteristics of Groupthink – denial without consideration.

As a aside, in June 1975, Harold Wilson tried to get rid of Tony Benn from this position as Secretary of State for Industry. He pressured Benn to resign by offering his a job of Secretary of Energy which would have put him in charge of the North Sea oil developments.

This would avoid having to publicly sack him, which would have been politically difficult given the narrow margin that Wilson held office by.

The UK Guardian article (December 29, 2005) – Foot led leftwing revolt over attempt to oust Benn – reminds us that Micheal Foot led a “leftwing rebellion” to protect Benn from Wilson’s attempts to remove him.

The irony is that Been actually accepted the job but Wilson had still “been humiliated” by the crude attempt to silence a major rival. Wilson’s days were numbered.

Another important aspect of the evolution of British Labour at the time was the use of depoliticisation to push a shift in direction.

Rogers (2009: 972) points out that the July 1976 cuts introduced by Denis Healey as an emergency measure:

… were achieved through a strategy of preference shaping depoliticisation by encouraging perceptions of crisis in the foreign exchange markets despite preferences for depreciation, and that the IMF settlement was broadly in line with fiscal cuts the Treasury believed necessary.

In other words, by appealing to an external authority (depoliticisation), Callaghan and Healey were able to hector their colleagues into accepting austerity as the only way forward, when, in fact, the Cabinet had alternative viable policy plans before them.

[Rogers, C. (2009) ‘The Politics of Economic Policy Making in Britain: A Reassessment of the 1976 IMF Crisis’, Politics and Policy, 35(5), 971-994.]

Colin Hay (1998: 528) constructs the issue in terms of whether the sorts of changes Healey were made (even though Hay is not discussing the 1976 crisis) were “necessary (summoned by an inexorable logic of economic globalisation), conditional (on the perception that such a logic is at work), or altogether contingent (emphasis in original).”

To better understand this distinction, Hay (p.529) notes that:

… the extent to which the parameters of the politically possible are circumscribed not by the ‘harsh economic realities’ and ‘inexorable logics’ of competitiveness and globalisation, but by perceptions of such logics and realities and by what they are held to entail (emphasis in original).

This relates to the “political power of (economic) ideas” (p.528).

In other words, the ‘space’ for alternatives to the Monetarist line (such as Benn’s interventions) at the time Healey was pushing through his austerity, existed, but were “no longer perceived to exist” (p.529).

Hay (p.529) agrees that the world changes but that:

… only a distinct absence of political imagination and/or a severe dose of political fatalism would imply that such changes narrow the range of alternatives to those which would subordinate social policy to economic imperatives, consigning the universal and redistributivist welfare state to a somewhat nostalgic rendition of the past.

[Reference: Hay, C. (1998) ‘Globalisation, Welfare Retrenchment and the ‘Logic of No Alternative’: Why Second-best Won’t Do’, Journal of Social Policy. 27(4), 525-532.]

It should escape our focus that at the time, the Monetarist surge in the academy had very little empirical support. It was based on an idea which had no robust validation within reality. For example, attempts to control the money supply growth by the Bank of England failed in the early 1970s.

The rise in acceptance of Monetarism was not based on an empirical rejection of the Keynesian orthodoxy, but in ALan Blinder’s (1988: 278) words ‘was instead a triumph of a priori theorising over empiricism, of intellectual aesthetics over observation and, in some measure, of conservative ideology over liberalism. It was not, in a word, a Kuhnian scientific revolution.’

[Reference: Blinder, A. (1988) ‘The fall and rise of Keynesian economics’, Economic Record, 64(187), 278-294.]

There was a concerted campaign including the publication of the Powell Manifesto and the funding of a burgeoning number of right-wing think tanks by those who saw gain in undermining the commitment to full employment and various financial and labour market regulations to promote the idea of Monetarism irrespective of the facts.

Please read my blog – The right-wing counter attack – 1971. – for more discussion on this point.

Callaghan and Healey bought into the ‘inflation-first’ narrative and abandoned the commitment to full employment. That did not mean they were immune to the vicissitudes of the rising unemployment in Britain at the time. But they were clearly prepared to allow unemployment to rise because they thought it would reduce inflation and allow the economy to stabilise at the natural rate of unemployment.

Pure Monetarist doctrine!

The perception created by the academics and think tanks was successful in making inflation appear to be a worse bogey person than unemployment.

Blinder (1987: 51) presented a compelling critique of this view and concludes that the political importance of inflation has been blown out of all proportion to its economic significance.

After dismissing the arguments that inflation imposes high costs on the economy, Blinder (1987: 33) noted

The political revival of free-market ideology in the 1980s is, I presume, based on the market’s remarkable ability to root out inefficiency. But not all inefficiencies are created equal. In particular, high unemployment represents a waste of resources so colossal that no one truly interested in efficiency can be complacent about it. It is both ironic and tragic that, in searching out ways to improve economic efficiency, we seem to have ignored the biggest inefficiency of them all.

[Reference: Blinder, A. (1987) Hard heads soft hearts, Reading, Addison-Wesley.]

As an aside, Blinder also challenged the perception that the costs of inflation were unbearable.

Blinder (1987: 45-50):

More precisely, is the popular aversion to inflation based on fact and logic or on illusion and prejudice? … Too many trips to the bank? Can that be what all the fuss is about? … Can that be all there is to the costs of inflation? The inefficiencies caused by hyperinflation are, of course, monumental. But the costs of moderate inflation that I have just enumerated seem meager at best.

And further, Blinder (1987: 51) also reacts to critics who lay all manner of societal ills on inflation at 6 per cent:

Promiscuity? Sloth? Perfidy? When will inflation be blamed for floods, famine, pestilence, and acne? … the myth that the inflationary demon, unless exorcised, will inevitably grow is exactly that – a myth. There is neither theoretical nor statistical support for the popular notion that inflation has a built-in tendency to accelerate. As rational individuals, we do not volunteer for a lobotomy to cure a head cold. Yet, as a collectivity, we routinely prescribe the economic equivalent of lobotomy (high unemployment) as a cure for the inflationary cold. Why?

But the Right was very successful in promoting the fear of inflation and reducing our concern for unemployment. And the Left – that is, British Labour were duped into pursuing the agenda as an elected government.

Those on the Left that resisted were isolated into a ‘socialist’ rump and accused of losing touch with the realities of the situation. But there were multiple realities – moulded into one perceived reality.

These manufactured (confected) perceptions were what allowed Callaghan and Healey to alter the course of history and shift Left politics towards the Right – a shift that has massive consequences in the present day.

Conclusion

The final instalment in the series covering the British-IMF crisis will analyse the events of November and December 1976 (the IMF negotiations), sum up the situation, and discuss the alternatives that might have been taken at the time.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

28. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost.

29. The metamorphosis of the IMF as a neo-liberal attack dog.

30. The Wall Street-US Treasury Complex.

31. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976.

32. British Left reject fiscal strategy – speculation mounts, March 1976.

33. The US government view of the 1976 sterling crisis.

34. Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well.

35. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976.

36. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

Paperback version of my Eurozone book now available

>My current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – carries an on-line price of £99.00.

It is now available in much cheaper paperback form for £32.00.

Also the eBook is available 36.27 US dollars from Google Play or 61.45 Australian dollars from eBooks.com.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Great stuff. I’ll send a link to young John McDonnell.

Hi Bill

Very interested to see you’re bringing Colin Hay into it: I have always been intrigued by his committment to distinguish between the causal effects of actual physical constraints and those produced by ideas and perception. His 1999 (I think) book on New Labour was probably one of the best, and his subsequent work on them has also been very enlightening.

That said, he (unfortunately) doesn’t grasp the full implications of being a sovereign currency issuer: for example, in a journal article that came out around 2003(ish) he actually advocated joining the Euro because he believed that the inability to use interest rates subsequently to control macroeconomic activity (which he had never had much faith in anyway) would have motivated the Blair government (and Brown treasury in particular) to resort to more active “Keynesian” fiscal policy: he even advocated fiscal remedies to increasing house prices rather than a reliance on interest rate policy that would make borrowing more expensive for everyone. It didn’t seem to occur to him (nor to me, reading it at the time) that joining the Eurozone would have made effective fiscal policy activism impossible anyway! It’s a shame really, because he clearly understood many of the other weaknesses of neoclassical economics (he for example noted in a 2004 paper that measurements of the “NAIRU” are usually generated by circular arguments proclaiming whatever the unemployment rate is at the time to be (also) the “only” unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation).

His book on comparative welfare states with David Wincott also serves as an excellent review of the literature demolishing “supply-side” arguments against welfare policies, but unfortunately (as to be expected for someone not well versed in MMT) their discussion of the “affordability” aspects was less helpful.

Colin Hay has moved to Science Po Max Planck Institute where this kind of thing is published.

Fourcade, Ollion, & Algan, “The Superiority of Economics”, November 2014:

“Economists also distinguish themselves from other social scientists through their much better material situation (many teach in business schools, have external consulting activities), their more individualist worldviews, and in the confidence they have in their discipline’s ability to fix the world’s problems. Taken together, these traits constitute what we call the superiority of economists, where economists’ objective supremacy is intimately linked with their subjective sense of authority and entitlement. While this superiority has certainly fueled economists’ practical involvement and their considerable influence over the economy, it has also exposed them more to conflicts of interests,

political critique, even derision.”

While he was still at Sheffield, Hay published a blog post entitled “Too important to leave to the economists: putting the ‘political’ back in political economy, The crisis has shown us that we can’t let mainstream economists continue setting the policy agenda” in October 2013.

While the Science Po is ranked as the 4th best university in political and international relations, it also has as a grad, Jean-Claude Trichet. Given Hay’s history in critiquing neoclassical economic theory and pitiful empirical analysis, while one can understand wishing to associate with an institution with such enormous resources, one can still wonder what took him there.

I should add that the MaxPo article was written by a sociologist, a research fellow, and an economist. It isn’t a neoliberal tract either, but suffers from a certain kind of style too common in sociology. And when they say that American sociology came out of economics, they neglect the considerable influence of the investigative journalists of the time, some of whom became eminent academic sociologists.

Larry, interesting information. Could you perhaps elaborate a bit on the ‘certain kind of style too common in sociology.’?

Lars, there are a number of ways in which sociologists write badly, the worst example of which was Talcott Parsons. It could be said if you wanted to be nice that he wrote German English. In the case at hand, the reader is often left to wonder what the point is that the authors wish to make and what their own position is. Some of this will be down to the journal for which the research paper is going, the Journal of Economic Perspectives. But that won’t be the whole story. Does this help? Of course, it may be that I have developed an allergy to this kind of writing. But I am not the only one. Dan Ariely says he hates writing for academic journals. One mathematician I know of who has a Fields Medal refuses to write for refereed journals anymore, so corrupt has the process become in his view. As the article shows, the incestuous character of the econ journals has for some time been a disgrace to the profession. Some economists think economics has become like a religion rather than a social scientific endeavor, such as Robert Nelson in his Economics as a Religion.

As can be seen from that short clip, Healey was a bit of a “bruiser” (although he also had another, rather refined, cultural side to him). Jim Callaghan, seen at the end smiling broadly (and rather smugly), was sometimes known as “Sunny Jim”. In private life he was also a farmer, and it is well known what a conservative lot farmers usually are …