It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism

This blog provides another excerpt in the unfolding story about Britain and the IMF. We pick up yesterday’s story with Britain mired in inflation and rising unemployment as the OPEC oil price rises impact in late 1973. The Tories under the leadership of Edward Heath were trying to deal with internal divisions between the traditional One Nation Conservatists (Heath) and the emerging, right-wing Monetarists. Edward Heath resisted the Monetarists through his term of office and used very traditional ‘Keynesian’ remedies in an attempt to reduce unemployment (for example, the ‘Dash for Growth’) but maintained the usual Tory hostility towards trade unions. His efforts in stimulating growth were stymied by the oil price rises, which spawned a major inflationary outbreak. The Tories blamed the unions and OPEC for the inflation, which, in part, was correct, but then invoked a period of damaging austerity which left the nation in a sorry state. They lost office in February 1974. In this blog, with Harold Wilson back in charge for the second time and his party becoming increasingly infested with Monetarist thinking, we consider the inflation problem in some detail, the lack of any credible evidence to support the Monetarist causality, as a means to understanding how disappointing Prime Minister James Callaghan’s famous 1976 Black Speech to the Labour Party Conference was in terms of maintaining the credibility of the British Labour Party then – and how it opened the way, not only for Margaret Thatcher to wreak havoc, but also for the emergence of the insidious New Labour, which continues to hobble progressive elements in the Party today. It was a major turning point in Left history and needs careful deconstruction.

The two major 1970s oil shocks and inflation

There were two major oil price shocks in the 1970s, which produced dramatic shifts in economic environment that the government around the world had to manage. In a sense, these shocks were without precedent.

The first occurred in October 1973 as noted yesterday and the second came in August 1990.

The second oil crisis in 1979 when oil production fell by around 4 per cent as a result of the Iranian Revolution and the global markets overreacted and pushed the price up by more than 200 per cent over the next year.

In 1980, further disruptions to the world oil supply occurred as a result of the Iran-Iraq War and oil prices did not fall again until half way through that year.

Following that disruption with expanded production from Mexico, Venezuela and Nigeria, oil prices fell significantly over the next 20 years.

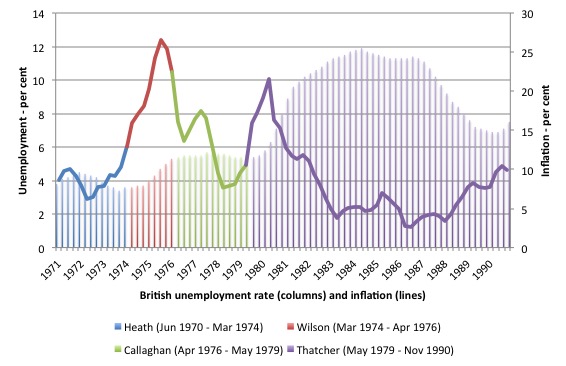

Consider the following graph which shows unemployment (bars) and the annual inflation rate (lines) for the various governments in Britain between 1970 and 1990 (so Heath to Thatcher with Wilson and Callaghan in between).

The last two annual inflation observations under Edward Heath’s tenure followed the first oil shock. Inflation rose from 9.2 per cent in the September 1973 quarter to 12.9 per cent in the March 1974 quarter as Harold Wilson took over.

It then clearly soared to a peak of 26.6 per cent in the September 1975 quarter and unemployment also rose sharply.

James Callaghan’s tenure was associated with declining inflation but persistently elevated levels of unemployment.

Then Margaret Thatcher assumed office in May 1979 and almost immediately inflation skyrocketed as did unemployment. The latter rise was due to the harsh austerity that her government inflicted at the same time as the US economy and other advanced nations entered a major recession.

Thatcher maintained these elevated levels of unemployment for most of her tenure and by the time she was replaced by John Major, British unemployment was still well above anything that had been seen in the 1970s before she took office.

The inflation rate was also higher again as she left office.

What caused the spikes in the inflation rate in early 1974 and again under Margaret Thatcher in late 1979 into 1980? Our analysis yesterday showed that the spikes were not associated with sharp spikes in the growth rate of the broad money supply, which would be required if the Monetarist causality was to make sense.

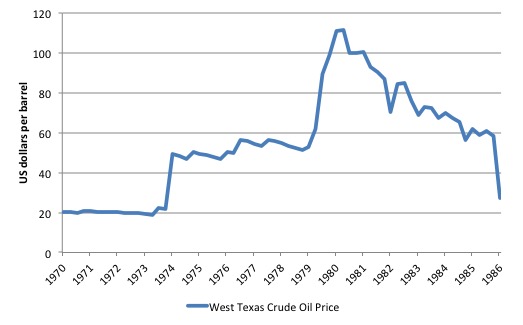

Consider the next graph, which shows the US dollar price per barrel of West Texas Crude Oil from the March-quarter 1970 through to the March-quarter 1986. Any of the crude oil price indexes give a similar temporal profile.

The two spikes in late 1973 and late 1979 are obviously related to the massive disruptions arising from the OPEC hikes and embargos in 1973 and the supply cuts in 1979.

There were domestic responses to those disruptions, which we will examine presently. But in terms of causation, the oil price hikes were instrumental and the acceleration of inflation rates throughout the world.

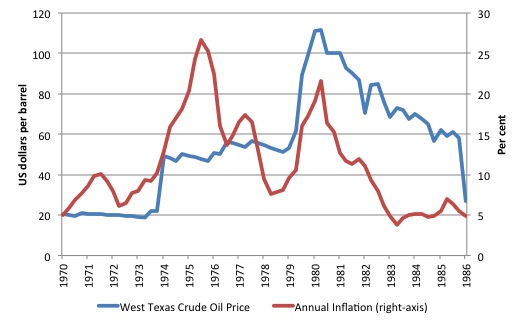

The next graph just adds the annual British inflation rate (right-axis) to the previous West Texas crude oil price (left-axis) to show the timing of the shifts in each time series.

In the same way that Edward Heath and Harold Wilson had to deal with a major supply (cost) shock, Margaret Thatcher was also caught out by world developments that were largely beyond her control.

The interesting discussion is then how they chose to deal with those shocks and how the public have understood (or not as is the case) them.

The non-existent Monetarist causality

The Tory Party under Heath already understood that the essential conditions for the Monetarist explanation of inflation to be credible were absent.

Denham and Garnett (2014) reported that (p.245):

In the early days of his government Heath had held a private discussion with Milton Friedman, and found the latter wholly unconvincing …

Heath, himself reflected on the tensions within the Tory Party at the time in his autobiography. He wrote that the Monetarist push within the Party (Heath, 1988: 521) “failed to cut any ice with the great majority of his colleagues”.

The Tory Monetarists continued to believe that the velocity of circulation was constant, one of the required conditions to establish Monetarist causality linking the growth in the money supply to the inflation rate, even though the empirical evidence was clear – the velocity was in decline at the time.

In their biography of Keith Joseph, a Tory Monetarist in Heath’s Cabinet, Andrew Denham and Mark Garnett say that “To an objective observer this statistics ought to have dealt a fatal blow to the monetarist case, since it implied that inflation should have been falling” (p.246).

But Tories such as Joseph didn’t blink in the face of this damaging reality and blithely continued to advocated free market policy changes and tighter control by the Bank of England on the money supply.

Later in Heath’s tenure as the Bank of England abandoned the so-called Competition and Credit Control (CCC), policy, which they had introduced in 1971 to control the money supply, the Tory Monetarists still could not accept that the money supply was endogenous – that is, not within the policy control of the central bank.

The Monetarist case is based on two arcane notions, one of which is just plain wrong, while the other has limited applicability during a recession.

The first notion is the rather technical sounding concept of the ‘money multiplier’, which links so-called central bank money or the ‘monetary base’ to the total stock of money in the economy (called the money supply).

It is this notion that led the Monetarists to believe that the central bank controls the money supply because it allegedly controls the money base.

The second notion then links the growth in that stock of money to the inflation rate.

The combined causality then allows the mainstream economists to assert that if the central bank expands the money supply it will cause inflation, which was the principle Monetarist claim.

As is often the case, the theory sounded intuitively obvious but very few people fully understand the theoretical route that is required to link central bank monetary expansion with inflation.

The ‘monetary base’ is defined in terms of the quantity of bank reserves held in accounts with the central bank and outstanding currency.

Macroeconomics students around the world rote learn the mantra that the money multiplier times the monetary base determines the money supply.

The money multiplier is just some number that scales up the monetary base to give a larger number, which according to the textbooks is the money supply.

The causality embodied in this mantra is an article of religious faith among mainstream economists and underpinned the attempts in the early 1970s by the Bank of England, infested with the emerging Monetarist thinking, to attempt to introduce so-called ‘monetary targets’.

The attempt failed categorically.

There were renewed attempts in the 1980s elsewhere, which similarly failed.

The monetary targets were just projections of the growth in the measured money supply, which the central banks claimed would be their primary policy vehicle for controlling inflation.

Central banks soon found out that they did not actually have control over the money supply. But the theory persisted.

To understand why the Monetarist causality fails we need to briefly understand the myth of the ‘money multiplier’.

The Myth of the Money Multiplier

Students are introduced to the money multiplier early in their studies. It is an article of faith in mainstream thinking. It is asserted, erroneously, that by manipulating the monetary base, the central bank can control the money supply.

Milton Friedman, the father of Monetarism, once said in relation to the US monetary system that:

… the Federal Reserve System essentially determines the total quantity of money; that is to say, the number of dollars of currency and deposits available for the public to hold. Within very wide limits, it can make this total anything it wants it to be … (Friedman, 1959a: 4; also Friedman, 1959b).

Later in 1968, as the Monetarists were gaining traction in the public debate, Friedman said during his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association, that the central bank should publicly adopt “the policy of achieving a steady rate of growth in a specified monetary total …” (Friedman, 1968: 16).

Unfortunately, like most aspects of the Monetarist doctrine, the theory doesn’t match the reality.

The ‘monetary base’ is measured as the notes and coins in circulation or in bank vaults plus bank reserves held at the central bank.

It is understood that central banks can add ‘money’ to the bank reserve accounts whenever they choose. They create money ‘out of thin air’. The money supply is defined in a range of ways – from very narrow (a small number of components) to broad (more components).

The narrowest measure, M1, includes only notes and coins in circulation and bank and cheque account deposits on demand (that is, funds that can be withdrawn instantly). Broader measures such as M3 include items such as longer-term deposits, which require more than 24-hours’ notice before withdrawal is permitted. The definitions also vary across nations.

The money multiplier is then defined as the money supply divided by the monetary base.

The textbook argument goes that the central bank controls the ‘base money’ in existence and then the act of credit creation in the private banking system multiplies this base up to create the money supply.

The determinants of the money multiplier need not concern us here but relate to various parameters in the banking system (for example, the quantity of notes and coins that depositors wish to hold and any required reserves that the banks must hold).

A simple story to get the concept across is that someone deposits a sum in a bank to earn some interest. The bank then keeps some of that deposit in reserve to meet the daily withdrawal behaviour and lends the rest out at a higher interest rate in order to profit.

The recipient of the loan spends the money, which ends up as a deposit in some bank or another. That bank, in turn, lends most of this new deposit out, and the process continues. The resulting money supply expands as these deposits multiply.

The conception of the money multiplier is really as simple as that.

There are two major flaws:

1. The empirical evidence clearly shows that empirical estimates of the money multiplier are not constant and so can hardly be used to make predictions. If one is to postulate a causal relationship between the monetary base and the money supply mediated by this so-called money multiplier then the multiplier would have to be stable or predictable. The multiplier has not exhibited stability anywhere and thus serves no useful basis for predicting the money supply.

2. The stylised textbook model of the banking system isn’t remotely descriptive of the real world. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) provides a detailed understanding of how banks operate.

Private banks do not wait for depositors to provide reserves before they make loans. Rather, they aggressively seek to make loans to credit worthy customers in order to profit.

These loans are made independent of a bank’s specific reserve position at the time the loan is approved. A separate department in each bank manages the bank’s reserve position and will seek funds to ensure it has the required reserves in the relevant accounting period.

They can borrow from each other in the interbank market but if the system overall is short of reserves these transactions will not add the required reserves.

In these cases, the bank will sell bonds back to the central bank or borrow from it outright at some penalty rate.

At the individual bank level, certainly the ‘price’ it has to pay to get the necessary reserves will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds.

But the reserve position per se will not matter.

For its part, the central bank will always supply the necessary reserves to ensure the financial system remains functional and cheques clear each day.

The upshot is that banks do not lend out reserves and a particular bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet by lending is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements that might be imposed by the central bank.

Loans create deposits, which are then backed by reserves after the fact.

These conclusions are devastating for mainstream economics and undermine the Monetarist claim that the central bank controls the money supply.

The Bank of England tells us that (p.25):

… it does not directly control the quantity of either base or broad money.

This insight is also confirmed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2008: 41):

In recent decades, however, central banks have moved away from a direct focus on measures of the money supply. The primary focus of monetary policy has instead become the value of a short-term interest rate. In the United States, for example, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announces a rate that it wishes to prevail in the federal funds market, where overnight loans are made among commercial banks. The tools of monetary policy are then used to guide the market interest rate toward the chosen target.

[References:

Bank of England (2014) ‘Money Creation in the Modern Economy’, Quarterly Bulletin, Quarter 1.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) (2008) ‘Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy’, Economic Policy Review, September, 41-56.]

Thus, monetary policy is not practised through attempts by the central bank to control the ‘money supply’ but rather through its capacity to set the short-term interest rate, the rate that gains all the headlines each month.

The reality is that the demand for credit by individuals and firms from their banks determines the money supply.

Business firms seek credit to meet working capital needs to produce goods and services to meet their expectations of sales.

Consumers also seek loans for a variety of purposes. These loans appear as bank deposits and so the ‘money supply’ expands. When the credit is repaid the money supply shrinks.

These flows are going on continuously and so fluctuations in the money supply measures published by central banks are just arbitrary reflections of the credit circuit: the borrowing and repayment of loans.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. Rather they determine the price at which it will supply reserves on demand by the banks.

A far better depiction of reality is that instead of the money supply being a multiple of the monetary base (the money multiplier story), the money supply brings forth the demand for bank reserves and so the monetary base responds accordingly.

The causality is thus reversed.

That is the case now and was the case in the early 1970s, which is why the CCC policy introduced by the Bank of England failed and why attempts to introduce monetary targets in the 1980s in various nations failed.

Further flaws in the Monetarist dogma – Money spent can buy goods and services rather than cause inflation

Monetarist causality invokes the Classical theory of inflation – the so-called Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), which in the public narrative is intuitively correct because it seems so simple.

While the QTM was formulated in the 16th century, the idea still forms the core of what became known as Monetarism in the 1970s.

In a blog the other day – The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government – I mentioned one memorable British House of Commons session, where the then Labour Chancellor Denis Healey was asked whether there was a need to “curb the vast wage increases now being sought in the nationalised industries” (see British House of Commons Hansard, HC Deb 27 March 1975 vol 889 cc667-73 – specifically cc671).

Healey responded (cc671-72):

I have set those out in detail in various statements … I must, however, remind the hon. Gentleman of one fact, which, since his right hon. and learned Friend referred yesterday to my speech at the Mansion House, may be worth stating again. I think that there is now general agreement on both sides of the House that the major cause of the inflation now racking Britain is the excessive increase in the money supply which took place in the last year of the previous Conservative Government …

Healey was just mindlessly channelling the QTM.

To understand why the British Labour Party walked into a quagmire of falsehoods during the early 1970s, which they have not been able to extricate themselves from, we need to understand what the QTM is based on or rather, requires to be a valid explanation of the inflation process.

The QTM postulates the following relationship: M times V equals P times Y, which can be easily described in words as follows. M is a symbol for how much money there is in circulation, that is, the money supply.

We have already mentioned V – the velocity of circulation, which is simply defined as the number of times per period (say a year) that the money supply ‘turns over’ in transactions.

To understand velocity, think about the following example. Assume the total stock of money is $100, which is held between the two people that make up this hypothetical economy.

In the current period, Person A buys goods and services from Person B for the $100 it currently holds. In turn, Person B uses the $100 to buy goods and services from Person A.

The total transactions equal $200 yet there is only $100 in the economy. Each dollar has thus been used ‘twice’ over the course of the year. So the velocity in this economy is two.

When we make transactions we hand over money, which then keeps being circulated in subsequent purchases. The result of M times V is equal to the total monetary transactions in the economy per period, which is a flow of dollars (or whatever currency is in use).

The P times Y is the average price in the economy (P) times real output produced (Y), which sums to what we call nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The national statistician estimates the total sum of all the goods and services produced to get real GDP and then values this in some way using the price level to get a monetary measure of total production.

So P times Y is the total money value of the output produced in the period.

At this level, the relationship M times V equals P times Y is nothing more than an accounting statement that says that the total value of spending (M times V) in a period must equal the total monetary value of output (P times Y), that is, a truism.

It is true by definition and thus totally unobjectionable.

How does the QTM become a theory of inflation?

The answer is that the inflation theory uses a sleight of hand. The Classical economists, who pioneered the use of the QTM, assumed that the labour market would always be at full employment, which means that real GDP (the Y in the formula) would always be at full capacity and thus could not rise any further in the immediate future.

They also assumed that the velocity of circulation (V) was constant (unchanged) given that it was determined by customs and payment habits.

For example, people are paid on a weekly or fortnightly basis and shop, say, once a week for their needs. These habits were considered to underpin a relative constancy of velocity.

These assumptions then led to the conclusion that if the money supply changed, the only other thing that could change to satisfy the relationship M times V equals P times Y was the price level (P).

The only way the economy could adjust to more spending when it was already at full capacity was to ration that spending off with higher prices.

Financial commentators simplify this and say that inflation arises when there is ‘too much money chasing too few goods’. It has crude appeal but is plain wrong.

The problem with the theory is that neither of the required assumptions holds in the real world.

First, there are many studies which have shown that velocity of circulation varies over time quite dramatically. Edward Heath clearly understood that fact but the Tory Monetarists such as Keith Joseph chose to deny it because it would have undermined their growing religious zeal for Monetarist dogma.

Second, and more importantly, capitalist economies are rarely operating at full employment. The Classical theory essentially denied the possibility of unemployment.

The fact that economies typically operate with spare productive capacity and often with persistently high rates of unemployment, means that it is hard to maintain the view that there is no scope for firms to expand the supply of real goods and services when there is an increase in total spending growth.

If a firm has poor sales and lots of spare productive capacity, why would it hike prices when sales improved?

Thus, if there was an increase in availability of credit and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will respond by increasing the supply of goods and services to maintain or increase market share rather than push up prices.

In other words, an evaluation of the inflationary consequences of OMF should be made with reference to the state of the economy.

If there is idle capacity then it is most unlikely that a growing money supply will be inflationary.

At some point, when unemployment is low and firms are operating at close to or at full capacity, then any further spending, whether funded by money creation or a reduction in deposits, will likely introduce an inflationary risk into the policy deliberations.

At the time the Monetarists were gaining traction in the public debate and policy makers were falling over each other to preach the doctrine, unemployment was rising (there was significant idle capacity) and velocity was falling.

There was no possible way the Monetarist approach to inflation possessed any explanatory power at all.

But British Labour fell for it and so the story unfolds.

Conclusion

The next instalment will consider the role of the trade unions in Britain in the early and mid-1970s especially in terms of their impact on inflation and their response the oil price shocks.

This will provide a clue to how British Labour should have handled the crisis in 1974 and why appealing to the IMF for loans in 1976 was ludicrous and a derogation of their responsibilities as currency-issuers.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

I will write a separate blog about this presently, but today we finally published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text – today (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 US dollars)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 US dollars)

It is retailing for at Amazon.com or £42.00 or €58.85 from Amazon Europe (UK).

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics

Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism

Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts

Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model

Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement

Chapter 10: Money and Banking

Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation

Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy

Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations

Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations

Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available the week after next.

Note: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

I’m certainly not a monetarist, but aren’t the monetarists right in their claim that there has never been a major prolonged inflation without an increase in the money supply, however money is defined. Monetary expansion may not be a sufficient condition for inflation, but it seems to be a necessary one. Even if the driving force of inflation is the wage-price spiral, this spiral still has to be validated by the central bank.

Regards. James

As can be seen from this UK government spreadsheet, the country was basically a net oil exporter over the whole Thatcher government, while it was a net importer before that. Before about 1976, it produced no oil in any quantity compared to its demand. So we would expect the effect of the two cost shocks (1973, and 1979-80) to be rather different. In the first case the domestic economy necessarily lost out to the external sector. In the second case, there were winners and losers within the domestic sector. It was possible for cost-push inflation to be balanced by increasing incomes, and general economic expansion.

James -look at Bill’s blog here:https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=33155

There is a graph that shows that monetary expansion needn’t be even a necessary condition

I like Lerner’s use of the term ‘flation’. In his book of the same title he writes:

‘ A major part of this book deals with the tragic consequences of policies based on the view that the inflation-deflation issue is a purely symmetrical matter of prices going up when there is too much spending, and going down whenever there is too little spending. These policies..consisted of treating inflation due to pressure by sellers (sellers’ inflation) as if it were demand inflation (inflation due to too much spending). They treated it by holding down total spending in the economy. Unfortunately this has lkittle effect on the rising prices of sellers’ inflation, but is very effective in deflating the economy.’

I am pleased that the price-wage spiral story is back into discussion, as core-CPI targeting is in effect a euphemism to target wages (the “inflexible” price number one).

One cannot compare 70s inflation with today’s inflation because they are measured in completely different ways. If the index used for the 70s was similar to today’s the 70s had rather moderate inflation, similar to today’s, and viceversa. Similarly for the unemployment rate. Today’s and the 70’s price and unemployment indices cannot be compared.

the usual neoliberal story of the completely imaginary “wage-price” spiral of the 70s and 80s, according to which nasty greedy workers pushed up their wages and this caused endogenous price inflation is wrong.

The story that is instead apparent from the numbers of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s is that the great inflation was the product of huge government “global security” oriented spending in the USA.

Devaluation of the dollar was in effect a “cram-down”. The oil producers refused to be crammed down and increased massively the price of their product after the dollar devaluation, the US decided to “accomodate” the huge exogenous price shock, to avoid undermining the USA government’s global security policy.

All this transmitted the cram-down shock wave through the value chain, and unionized workers reacted to sharply rising prices driven by oil and commodity inflation by demanding higher wages, which was temporarily successful. At that point because of the exogenous price shock caused by the falling dollar and oil and commodity producers and unionized workers resisting the cram-down it was creditors and businesses who were forced to take the cram-down as massive losses on existing bond valuation because of increasing nominal interest rates and much reduced profits.

Eventually creditors and businesses fought back and thanks to Volcker and Reagan managed to push the costs of the cram-down onto unionized and non-unionized workers, and debtors, and the cram-down continues today: in the USA median hourly wages have been flat or declining since 1973.

Bill,

Of course, the other thing monetarists seem to misunderstand is that money can also be saved instead of spent. Most people on lower incomes save at least some money in their current accounts for a rainy day, and this would not show up in the monetary aggregates. They prefer to keep it in a current account because the may need access to it unexpectedly, or because they do not know what other accounts they could use.

Kind Regards

Fascinating. So how do I explain all of this to folk in laymen’s terms?!

Dear Scott Egner (at 2016/03/17 at 9:07)

We have a book coming out soon which will edit this material down to layperson level.

best wishes

bill

‘and the second came in August 1990.

The second oil crisis in 1979’

Sorry I’m a little late in my proof-reading

“Of course, the other thing monetarists seem to misunderstand is that money can also be saved instead of spent.”

They assume by loanable funds that it is all spent.

The proof of endogenous money throws the cat firmly amongst those pigeons. Not only is V variable – contrary to early monetarist dogma – but M has a whole dynamic structure of its own

I do not see any mention in Bills article regarding the ending of the Bretton Woods Gold Standard in1971 and the commencement of the Petrodollar system in 1973. Money no longer had any asset backing from then.

The ending of the Gold Standard gave the private banking system carte blanche to issue loans and was the main cause of housing inflation in the UK even today.

Further to blame the unions for inflation is incorrect. The unions did indeed strike/agitate strenously during the ’80’s , but this was to protect their wages which had suffered from inflation. The main cause of this inflation was excess/uncontrolled credit creation from the private banking system.

“They assume by loanable funds that it is all spent.”

How do deficits arise in monetarist thinking then?

Failure went further than Monetarism. It even included the unions in the 1970’s and 80’s; indeed failure seemed to be endemic to much of that post-war period.

The big strikes in the energy, heavy industry and transport sectors were tied in with the goal of maintaining their dominance. There was a valid reason for this confrontation; many thousands of jobs were at stake, irrespective of maintaining real wage levels. There was also the not inconsiderable political dimension.

The Conservative desire to take on unions was shared, ironically, by a significant number of voters who recognised the power possessed by strong unions, over and above their own more limited influence. And this power was able to mould government economic policy even if it meant a misallocation (in terms of efficiency and progressive development) of scarce resources.

That period didn’t of course, have to be mired in such belligerence but weak governments struggle to win over powerful unions when it comes to industrial upheaval, and strong governments leave themselves open to accusations of favouring Capitalistic remedies at the expense of ordinary citizens.

In arguing their case, economists often fail to marry up the goals of humanitarian ideals and commercial enterprise. Instead, the controversy subsides into a biased ideological quagmire.

“How do deficits arise in monetarist thinking then?’

Governments prising hard earned money out of the hands of the private sector with excessive interest rates.

Hence ‘crowding out’.

The big strikes had nothing to do with their dominance at all

While I can’t speak about the English situation however they were in the same situation as the Australian workers were

They could quite clearly see that the massive burst of inflation was going to have a serious impact on the workforce as a whole so very early on the unions went to the managers here who owned all the big mines which were US companies at the time and asked them to sit down and negotiate with them to ease the effect on the workers that both the inflation and the push towards automation that it was bringing about

The bosses arrogantly turned around and told the union reps to “Fuck Off ” literally and the unions made them a promise that they would keep to their dying days

That they would send them as close too the wall as they could but one way or another they would get every entitlement the workers were due out of them and they did

While some didn’t most out here got what they were owed and that was thanks to the unions

many thanks bill, as child of the 70’s who’s parents were subjected to the blinding propaganda of that era (and tried to pull the wool over my eyes) its great to read these words.

if your ever in london, i will gladly buy you a pint!

I haven’t paid much attention to economics since it struck me as weirdly fake at school. Now I’m looking, I’m seeing lots of knowledgeable folk, but few who have a gift for teaching that you do!

Keep up the good work!