I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

One of the first things that conservatives (and most economists which is typically a highly overlapping set) raise when Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents suggest that increased deficits are essential to reduce mass unemployment is the so-called balance of payments constraint. Accordingly, we are told that the capacity of a nation to increase domestic employment is limited by the external sector. And these constraints have become more severe in this age of multinational firms with their global supply chains and the increased volume of global capital flows. I will address the specific issue of a balance of payments constraint on real GDP growth (that is, the limits of fiscal stimulus) in a future blog. But today I want to consider the so-called Exchange Rate Pass-Through (ERPT) effects of that are part of the balance of payments constraint story. The mainstream narrative goes like this. Higher wage demands associated with full employment and/or stronger imports associated with higher fiscal deficits lead to external imbalances due to rising imports and loss of competitiveness in international markets (eroding export potential). In a system of flexible exchange rates, the currency begins to lose value relative to all other currencies and the rising import prices (in terms of the local currency) are passed-through to the domestic price level – with accelerating inflation being the result. If governments persist in pursuing domestic full employment policies the domestic inflation worsens and the hyperinflation is the result, with a chronically depreciated currency. Real standards of living fall and a general malaise overwhelms the nation and its citizens. I am sure you have heard that narrative before – it is almost a constant noise coming from the deficit phobes. Like most of the conservative economic claims and I include the austerity-lite Leftist parties in this group, it turns out that reality is a bit different. Here is some discussion on that issue.

Part of the austerity logic is that to increase employment and maintain both stable inflation and external balance, a nation has to reduce unit labour costs or in the modern terminology engage in so-called internal devaluation.

Successful nations achieve reductions in unit costs by increasing productivity, through a range of measures including maintaining first-class education and health systems, high quality skill development structures and strong new investment in best-practice technology.

It is clear that these initiatives take time to plan and implement and deliver returns in the future. Many of these policy areas are also among the first to be targetted for cut backs when conservatives embark on fiscal austerity.

In the mid-1970s, as most advanced nations were mired in stagflation (mass unemployment and elevated and rising inflation rates), the mainstream economists claimed that the only way that nations could be successful in reducing unit costs in the short- to medium-term quest was to cut workers’ wages and/or entitlements.

It was argued that these initiatives could be quickly implemented but would also encounter strong real wage resistance from powerful unions.

The solution then was to undermine the capacity of unions to defend the real wage levels of their members.

Tied up in all of this was the belief that if a government tried to push growth faster than some (theoretically-derived) natural rate of growth (and this rate is part of the balance of payments constraint literature) then not only would rising labour costs render a nation uncompetitive as unions took advantage of the higher employment to press ever-increasing wage demands, but the rising income would push out imports and lead to a balance of payments crisis and exchange rate depreciation would occur.

The argument then contends that the Government has to step in and introduce contractionary fiscal policy and/or tighter monetary policy to suppress the wage pressures, reduce import demand and attract higher levels of capital inflow.

It is argued that under these conditions are nation is forced to follow a ‘stop-go’ growth path, where periods of stimulus and growth push the economy up against the balance of payments constraint, which then necessitates an economic downturn (not recession) to restore balance.

While the ‘stop-go’ terminology was really born in the period of fixed exchange rates (Bretton Woods period), it is survived into the flexible exchange rate era.

If we take these arguments at face value (which is the topic of another blog), then the question that arises is why should a nation be worried about its exchange rate falling relative to other currencies, if it has been able to achieve full employment?

It is argued that under flexible exchange rates, nations can ‘import’ inflation from other nations, which negate real income gains made through domestic expansionary policy.

Exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) refers to the impact on domestic prices of a change in a nation’s exchange rate. In other words, it directly relates to the extent to which a nation imports inflation when its exchange rate depreciates and/or suppresses domestic inflation pressures when its exchange rate appreciates.

The conventional wisdom is that when the, say Australian dollar, depreciates, the prices of all imported goods rise in local currency terms, which then ‘pass-through’ into the domestic price level, which is typically measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

One of the mainstream claims, therefore, is that fiscal stimulus becomes self-defeating because it ultimately results in increasing external deficits and accelerating domestic inflation, via the exchange rate depreciation. This is in addition to any inflationary impacts that are claimed to occur through higher wage demands as a result of stronger employment growth.

In terms of ERPT, there are two distinct stages that are identified in the conceptual process, both of which can be statistically examined and summed to estimate the extent of the pass-through on the CPI.

- First, fluctuations in the exchange rate are reflected in import prices, especially where the goods are priced in foreign currencies.

- Second, the changing import prices then influence the evolution of the CPI.

Before we get into that a few words about price indexes will be useful.

Most national statistical authorities publish a range of ‘price’ index measures. The Australian Bureau of Statistics, for example, publishes an Import Price Index within its – International Trade Price Indexes – which were last published in December 2015.

Table 13.8 tells us that the Import Price Index (IPI):

… measures changes in prices of imports of merchandise into Australia. The index numbers for each quarter relate to prices of imports landed in Australia during the quarter.

The ABS say that “All prices used in the IPI are expressed in Australian currency”. Why is that important?

The ABS say that:

As a result, changes in the relative values of the Australian dollar and overseas currencies can have a direct impact on price movements of imports that are purchased in foreign currencies. Prices reported in a foreign currency are converted to Australian dollars using the relevant exchange rates at the date of change of ownership. Where foreign currency purchase prices use forward exchange cover, the prices used in the index exclude the forward exchange cover.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the best-known domestic measure of inflation although central banks typically use modified measures of the CPI to estimate so-called ‘core’ or ‘underlying’ inflation. This usually involves taking out volatile components such as energy prices and/or trimming outlier observations.

According to the ABS Information Paper (6461.0) – Consumer Price Index: Concepts, Sources and Methods:

The CPI is a current social and economic indicator that is constructed to measure changes over time in the general level of prices of consumer goods and services that households acquire, use or pay for consumption. The index aims to measure the change in consumer prices over time. This may be done by measuring the cost of purchasing a fixed basket of consumer goods and services of constant quality and similar characteristics, with the products in the basket being selected to be representative of households’ expenditure during a year or other specified period.

The point is that it is the prices of final goods and services that are computed in the CPI.

This definition is internationally accepted and was resolved at the Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians convened by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 2003.

I won’t go into how the CPI is constructed here. That is a lifetime of writing in itself. The cited Information Paper is good reading though if you like technical detail. It is also applicable to most advanced nations at least although terminology might vary from country to country.

The impact of import prices on the CPI is, in part, determined by the proportion of total goods and services that are indeed imported and included in the CPI ‘basket’ of goods and services.

Further, the the weight of these classes of goods and services in the basket that comprises the CPI is clearly important.

The ABS have recently began publishing its “International trade exposure series”, which nets out the impact of ‘tradables’ and ‘non-tradables’ on the CPI.

The ‘Tradables component’:

Comprises all items whose prices are largely determined on the world market.

The latest – CPI Analytical Series – estimates that the tradables component adds about 39.8 per cent to the variation in the CPI, the remainder being the non-tradables component.

The ERPT effect also depends on other factors including:

- The expected magnitude of the depreciation/appreciation – and the expected persistence of the new exchange rate level or range. If firms expect the new level to be more or less permanent (within their planning period at least) then they will have a different view than if they think it will shift back again soon. Existing inventory also has to be taken in to account (given it would reflect previous exchange parities).

- The state of the domestic economy – pass-through might be higher in good times because there is less need to compress profit margins.

- The costs involved in adjusting the catalogue of prices on offer. Firms offer millions of items for sale and it is very costly to adjust the price of each when exchange rate fluctuations occur. Further firms that continually alter prices lose faith with their customers who plan their consumption on the basis of catologue prices. This is less of an issue with the growth of Internet commerce.

- The extent to which imported goods can be substituted for with locally-produced goods. For example, in Australia, we regularly have large exchange rate swings and these manifest in shifting holiday locations – Swiss Alps skiing holidays or East coast Australia camping trips – these type of goods and services have what economists call a high “elasticity of substitution” meaning that it is easy to not book a flight to Europe and go to the beach in Australia instead when the price changes.

What is the evidence?

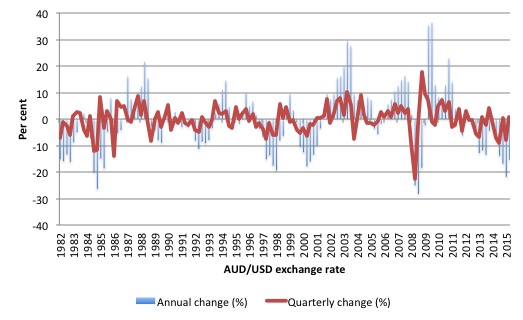

Consider the following graph, which shows the annual percentage change in the Australian-USD exchange rate from the September-quarter 1982 to the December-quarter 2015 (in blue columns) and the quarterly change (red line).

By any standards, the parity fluctuates a lot. In June 2001 it was down to 50.9 US cents per Australian dollar. Three years later it was up to 75 US cents. Then above parity a few years after that only to be back to 72 US cents in December 2015.

Australia is a very wealthy, high income nation which undergoes regular and large variations in our exchange rate. It is a good test case for ERPT.

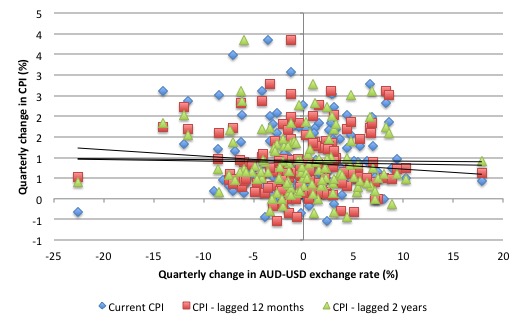

Consider the following graph which shows the relationship between quarterly percentage fluctuations in the Australian-USD exchange rate (rising rate is an appreciation) and the quarterly changes in the CPI.

I have created three CPI series – the current value (blue), lagged by 12 months (red) and lagged by 24 months (green). Some argue that the impact of exhange rate fluctuations take time to work their way through to the domestic price level. So the lags out 12 and 24 months should pick up the lagged effect if there is one.

The linear black lines are just simple regressions. If there was a strong relationship as described in the mainstream theories (and the textbooks) then we would expect the regression lines to be visibly sloping downwards and the relationship between the two pairs of time series to be statistically significant.

The data range is from the September-quarter 1982 to the December-quarter 2015. So there is enough time for these effects to be disclosed.

The upshot is that there is no discernible effect of percentage changes in the Australian dollar parity against the USD (as an example) and the percentage change in the CPI.

I constructed the same graph for just the tradable component of the CPI and a similar result was derived.

Just for fun, I also constructed some quite complicated dynamic time series regression models (with all the tricks) to test higher and intermediate order lag effects controlled with other factors (such as domestic growth rates) and still found no significant relationship at any lag.

Conclusion: percentage shifts in the AUD/US exchange rate (quarterly or annually) do not seem to have a significant impact on the Australian CPI or sub-measures of the CPI.

So why do we believe the conservatives when they claim that an exchange rate depreciation will impart dangerous inflationary forces into the domestic economy, which will undermine any attempts to use increased net public spending (that is, fiscal deficits) to reduce the unemployment rate back to full employment?

A huge empirical literature exists on this topic and it is a topic that central bank research department’s are particularly interested in, given the bias in monetary policy these days towards inflation control.

A Bank of Canada study – Has Exchange Rate Pass-Through Really Declined? Some Recent Insights from the Literature – finds that:

…. the correlation between changes in consumer prices and changes in the nominal exchange rate has been quite low and declining over the past two decades for a broad group of countries …

there is fairly convincing evidence to suggest that measured short-term ERPT to consumer prices has declined …

In relation to pass-through to import prices:

1. The study suggests that the “decline in ERPT to import prices” is due “to increased trade integration, because supply chains have become more interconnected and globalized”.

This allows vertically-integrated multinational firms to shift production around natinos where currency movements are favourable.

Further, “large importers have significant market power, in particular, the power to discriminate between suppliers based on location” and mitigate any exchange rate impacts on import prices.

2. The “swift and significant integration of emerging economies into global markets may have contributed to the fall in ERPT to import prices in many industrial countries by increasing the prevalence of pricing-to-market (PTM)”.

3. “The decline in pass-through to aggregate import prices can therefore be attributed to changes in the underlying composition of products in each country’s import bundle, particularly the move away from commodities and towards products in sectors with higher degrees of product differentiation and lower degrees of ERPT, such as manufacturing”.

In relation to the pass-through to the CPI:

1. “The large non-tradable component in distribution margins thus significantly insulates consumer prices from exchange rate movements” (Source).

2. “increased competition among retailers in the local market can also lead to a decline in ERPT to consumer prices”.

The Bank of Canada study also argues that:

the expenditure-switching effect helps to redirect consumption and investment in a country with a trade deficit away from imports, as the exchange rate depreciates, making the country’s exports more attractive to foreigners … [thus] … The benefits of a flexible exchange rate may also be larger than they appear …

A 2014 New Zealand central bank study – Exchange rate movements and consumer prices: some perspectives – found that:

Petrol prices adjust substantially and quickly. But a significant share of New Zealand’s imports appear to be priced for the local market and, however they are priced, there is a large domestic distribution component for most tradable goods. That means prices for traded goods in New Zealand will adjust by a smaller percentage than any given percentage movement in the exchange rate, and may diverge from those in the rest of the world for protracted periods.

A 2015 Bank of England paper – Much ado about something important: How do exchange rate movements affect inflation? – provided three broad conclusions:

First, contrary to common belief, exchange rate movements don’t seem to consistently have larger effects on prices in sectors with a higher share of imported content. Second, exchange rates don’t seem to consistently have larger effects on prices in the most tradable and internationally-competitive sectors. Third, the effects of exchange rates on inflation – and even just on import prices – do not seem to be consistent across time. Most of what I learned in grad school on this topic no longer seems to apply.

It argued that if we examine “what drives the initial exchange rate movement”, further insights can be gleaned.

So, for a supply-side shock will have different ERPT effects than in a situation where the exchange rate is depreciating at the same time a nation is experiencing “strong domestic demand” or “global demand”.

It says that when “exchange rate movements result primarily from changes in domestic and global demand, they are associated with very different inflation dynamics than other types of shocks – undoubtedly due to the support to company sales from stronger demand.”

Conclusion

This is one of those cases where economists in classrooms or in the media just sprout textbook mantras without any coherent understanding of the empirical content of their statements.

Sure enough we can draw complex diagrams that show conceptually how ERPT can work – with arrows going everywhere from this box to that box and so on – but there is a real world out there.

The real world tells us that the ERPT is weak in most nations for which coherent empirical research has been conducted.

There is some pass-through but not enough to trigger a hyperinflation and certainly not enough to derail a full employment program based on stimulating domestic demand.

Interestingly, the increased globalisation of supply chains and vertical integration of multinational firms has reduced each nations’ CPI response to exchange rate fluctuations.

So next time this issue is raised at your dinner table you know what to say!

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The conventional wisdom is that when the, say Australian dollar, appreciates, the prices of all imported goods rise in local currency terms, which then ‘pass-through’ into the domestic price level”

If such a thing could happen doesn’t that suggest that competition in the domestic market is insufficient? Yet if you’re running at full domestic output then domestic competition should be at its most intense.

One of the key pieces of data from the recession was the collapse in the strength of the British Pound. It fell by 20% from an elevated level down to what it was in 1997. There was quite a big impact on the producer price index, but very little impact on the consumer price index and nothing at all on the wages index.

And of course that was because the level of demand was insufficient to sustain the supply. Competition for customers was intense and substitution happened at an accelerated rate.

So ISTM that the policy output from the evidence is clear. Ensure the competitive part of your economy is subject to intense competitive pressure in all markets, fix price contract the non-competitive bit at the prices you want to see – regardless of CPI – and allow firms that are excessively borrowed in foreign currency fast track administration programmes to refinance from the banks in the domestic currency.

“when the, say Australian dollar, appreciates, the prices of all imported goods rise in local currency terms”

I suspect a typo – shouldn’t it be “depreciates” that is goes weaker e.g. from 1.05USD/AUD to 0.7USD/AUD? This makes imported goods priced in USD dearer in the local currency (AUD).

Yep, has to be a typo.

Very interesting and incredibly detailed piece Bill thanks as always.

One thing I’m curious about is hedging of foreign exchange movements that large companies use. This would only make the effects of currency movements even less influencing on pricing and hence inflation. It can Ofcourse work the other way with a bad choice of hedging but from what I’ve seen with active competition profits are impacted rather than price. I’m thinking in particular the examples of major airlines hedging their bets on fuel prices with some big winners and losers. A Google search brings up a number of articles both current and from the past couple of years.

This is a very interesting article, Bill. I think that you’re mostly right.

But I still think that this is a case-by-case issue. The case of the UK in 2008 has always been very interesting to me. It highlights what could be a substantial vulnerability on the part of an economy whose manufacturing has declined massively, whose currency is tied up with banker inflows and whose industry is interlinked into global supply chains.

The sterling depreciated substantially in 2008 – somewhere around 20-25% – because the banks froze up. What happened after this was interesting. Import prices rose substantially. But export prices ROSE TOO!

Why? Because many of the exports used imports as inputs because industry is so stitched into the global supply chain. This meant that the depreciation led to a contraction in domestic income with no increase in domestic competitiveness. The Treasury did a survey of this. You can find it here:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/elmr/explanations-beyond-exchange-rates/trends-in-the-uk-since-2007/art-uktrade.html

The UK then went on to experience inflation. While the rest of the world was slipping into deflation the UK had inflation of over 4%. If the labour market hadn’t been so slack I’d imagine that this inflation could have been easily over 6% and may well have gotten stuck in the system.

I’m totally non-dogmatic on this. But I think that this case should be considered. From a scientific point-of-view it is interesting and should be studied. Perhaps it is unique to Britain. I think that it probably is. But it is a very volatile situation so far as I can see. If foreign demand for sterling dried up because bankers got spooked – say, by an election of Corbyn – then the sterling could decline. All the adjustment would be felt in real income terms with little short-term increase in competitiveness. If the labour market was tight this could lead to an uptick in inflation. I think that the BoE would raise rates aggressively in such a scenario.

I’m sympathetic to the above post. I think what you have written is broadly true. In cases like Canada, the US, Australia, Japan and most European countries depreciation is no big deal. But in countries like Britain I’m not so sure. I think that the evidence here should be looked at with an open mind and the consequences of it thought through.

Bill,

Locals taxes should also be a factor e.g. in UK fuel duty with VAT then added means prices rarely dip below £1 /litre even with current oil prices and $ rates.

Regards

Dear Adam K and Lance

Thanks. It was a typo.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

We should distinguish between real and nominal exchange rate variations. If there is a nominal devaluation but no real devaluation, then that should have no effect on the price level. Let’s say that the Brazilian real is worth 0.5 USD at T1. Between T1 and T2, the inflation in Brazil is 50% and in the US 20%. If at T2, the real is worth 0.4 USD, then there has been a nominal but no real devaluation. If exchange rate fluctuations accurately reflect differences in inflation rates, then there is no imported inflation. Nor is there a loss of competitiveness if the country with the higher rate of inflation undergoes a devaluation which maintains its real exchange rate unchanged. That’s a huge advantage of flexible exchange rates. It allows countries to have different inflation rates from their trading partners without importing inflation or losing competitiveness. Unfortunately, exchange rate variations are often caused more by short-term financial flows than by different price levels.

Regards. James

“While the rest of the world was slipping into deflation the UK had inflation of over 4%.”

That’s not strictly true. The UK pattern followed the trend across the EU – but at a slightly higher rate. And of course we didn’t get the unemployment that occurred elsewhere in the continent.

Plus you have to factor in the under inflation caused by the massive rise in the exchange rate that occurred after 1997. Gordon Brown kept inflation down with financial speculation that kept the pound very high.

So 2008 can just be seen as catch up as things snapped back to their usual configuration.

“If foreign demand for sterling dried up because bankers got spooked ”

How can foreign demand for sterling dry up? That is how the countries that export to the UK are able to export more than they import. For the demand to ‘dry up’ the exports have to stop coming. Why is China going to allow that to happen if it is still in export-led growth mode? It maintains a currency peg for a reason – to keep its people in work by importing demand from the rest of the world. Japan does the same.

Shuffling capital around may create short term movements, but unless there is a patsy in the market (the central bank being stupid usually or private banks lending for speculation) it all ultimately gets driven by the underlying trade dynamics.

” I think that the BoE would raise rates aggressively in such a scenario.”

They may do. But they didn’t do last time. Have you wondered why?

Neil,

(1) I think UK inflation was higher and much commented on at the time.

(2) Capital inflows can dry up long-term. Especially in terms of portfolio investment. China has no control over this. There are also issues surrounding the 2008 devaluation that we simply do not understand and appear tied up with the fact that the City sloshes daily FX transactions and so forth around.

(3) Because the economy was in recession. I’m talking about a scenario that is close to full employment.

Phil,

I agree with Neil above, and also direct you to the movements in VAT. In 2009 the government temporarily lowered VAT from 17.5% to 15%. This influenced the CPI. In 2010 VAT was returned to 17.5%. The following year the Tory government raised it again to 20%. So there is a lot of noise in the UK’s headline CPI relating to VAT changes.

Charles,

VAT was raised in 2011. Inflation was well above global trends by the end of 2009/beginning of 2010.

I think the general consensus is that this inflation was due to the 20-25% depreciation of the sterling in an economy heavily reliant on imports even for foodstuffs.

Just this paper is material for a paper, if you haven’t written it already.

To follow that up, here’s an article around the time of the VAT hike:

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/feb/15/cost-of-living-vat-rise

As you can see, inflation was already running at 3.7% in December – very high for this period – and was forecast to increase by a measly 0.5% because of the VAT increase. The forecasts proved approximately correct.

Something else was definitely driving the bulk of inflation.

“If foreign demand for sterling dried up because bankers got spooked ”

Does not make any sense at all.

The reason countries export to us in the first place is to get their hands on £’s. They see it as one of the safest investments in the world which then allows them to do many other things.

Like move some into a savings account at the BOE or buy properties in London which will give them a great return. Or buy up some of our private sector.

Phil,

“Inflation was well above global trends by the end of 2009/beginning of 2010.”

This was precisely the time (i.e. January 2010) the Labour govt raised VAT back to 17.5% (from 15%) which the ONS have said would have added between 1% and 1.5% to headline CPI.

Charles,

So a VAT increase from 15% to 17.5% in 2010 led to a 1-1.5% increase in CPI. But a VAT increase from 17.5% to 20% in 2011 led to an increase of only 0.5% in the CPI?

I don’t see how that works.

Maybe look at it this way. Here are the US figures during the crisis:

2008: 3.8%

2009: 0%

2010: 1.6%

And the UK figures:

2008: 3.6%

2009: 2.2%

2010: 3.2%

Your VAT increases start in 2010. Yet it is clear that the higher trend had started in 2009. Note that the sterling depreciated in the second half of 2008.

I think the causality is clear. I think the VAT increases had maybe a 0.5% impact on the CPI in both 2010 and 2011. But the main increase was driven by the depreciation. You can see it in the import price statistics very clearly.

Phil,

I’m not saying that VAT changes explain everything, just that you have to take them into account.

You can look at the ONS’ CPI-Y measure of inflation which excludes the maximum effect on prices of changes to indirect taxes like VAT:

2008 3.8%

2009 3.4%

2010 1.7%

2011 3.0%

I don’t think the maximum effect actually took place, but I read somewhere that surveys of companies suggested that when VAT rises 2/3rd of the burden is past to the consumer. When it falls only 1/3rd of the benefit is past onto the consumer. The point is this creates a lot of noise.

I agree that no one has ever explained entirely what has happened in the UK that has been different from the rest of the world, and devaluation will have had some impact on CPI, but probably not nearly as much as most people would think.

Kind Regards

“I think UK inflation was higher and much commented on at the time”

It was higher, but it followed the pattern of the inflation across the EU. EU *average* inflation was 3% when the UK was above 5%.

Looking back at Oct 2011, the CPI was 5%, excluding volatiles was 3.4% with the majority of the rest of the increases coming from energy induced cost rises in administrative price sectors (Transport, Education, Hospital Service, Water).

None of this translated into wage rises and was way lower than the producer price indexes where input prices were up 14.1% on a downward trend.

“Capital inflows can dry up long-term. Especially in terms of portfolio investment.”

Not in a floating rate exchange system they can’t. There is no such thing as capital flows in such a system. Somebody always ends up holding the baby. All you can get is a reduction in loans outstanding, which as we have seen brings out the central bank and the government to prop things up. You can have an idiot government, like we have in the UK, but that’s a different point.

“Because the economy was in recession. I’m talking about a scenario that is close to full employment.”

In which case you have to first explain how we deal with the four million without work that want it and 1.5 million short of work.

Otherwise it’s another of those ‘assume we are at light speed’ arguments.

Charles,

Yes probably had an effect. Be careful with business surveys though. They’ll always try to justify price increases by blaming government taxation. They’ll typically get at least five newspaper articles out of that sort of statement.

Neil,

I really don’t get your views on capital account. There are lots of examples where capital gets spooked and flees. Asian crisis is the classic case in the 1990s. We’re about to see another in Turkey if you want to watch in real time. Keep your eyes peeled.

“There are lots of examples where capital gets spooked and flees. ”

It can’t in a floating rate system. To swap £s for $s you have to have someone in the other direction. All you need to do is ban bank lending for currency settlement on pain of loans being declared illegal and a gift of shareholders funds and watch liquidity dry up. Unfortunately the people in charge are morons.

Hello Bill,

but Russia had a strong pass-through effect on CPI after rouble depreciation. Do Your examples not about emerging markets?)

Bob,

I’m afraid that it can. I’m not sure why this myth that sharp capital outflows cannot provoke major currency and banking crises floats around amongst MMT proponents. I think that proponents should make some clear statements in this regard because their followers – of which I consider myself one – appear completely confused on this simple point.

In the meantime, there is plenty of solid empirical work such as this:

http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/episodes-of-large-capital-inflows-and-the-likelihood-of-banking-and-currency-crises-and-sudden-stops_5kgc9kpkslvk-en

But nobody has restricted bank lending when it comes to currency settlement. This si the problem described in this post:

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2016/01/the-procrustean-economy.html

“The conventional wisdom is that when the, say Australian dollar, depreciates, the prices of all imported goods rise in local currency terms, which then ‘pass-through’ into the domestic price level, which is typically measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI).”

I’m not saying this because you said it, but this seems illogical. I would have thought that if people were importing more than normal this means domestic sales would be lower than otherwise, therefore pushing domestic prices down not up. And even if this causes the exchange rate to depreciate and then import prices go up as a result then people will stop importing, not continue doing it!

I’ve been following the RBA quite closely and they keep beating this drum which says; a higher AUD would result in a slower pick-up in growth and inflation.

But I think your point is stop worrying about the exchange rate and so something about the employment rate

Very interesting topic. Professor Bill Mitchell, do you have posts about the same topic but on developing countries? Thank you. I have been researching on external constraints in Latin American countries and I have found a strong correlation between the investment growth rates and imports growth rates (the R squared ranges from 0.50 to 0.80, it is stronger after 1980). The relationship also is strong in the case of capital goods imports. It may suggest that the developing countries depend on capital-goods imports and could find a constraint if their capacity to import is weakened. Effectively, in the case of Australia the correlation is weak (R squared=0.22). The following is the link where you can see the correlations: https://economikapital.com/index.php/2021/10/07/the-south-american-economies-external-constraints-a-comparison-with-australia-and-east-asian-countries/

Britain imports 40% of its food

Britain imports 37.5% of its energy

It must be vulnerable to Exchange rate led inflation