I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 2

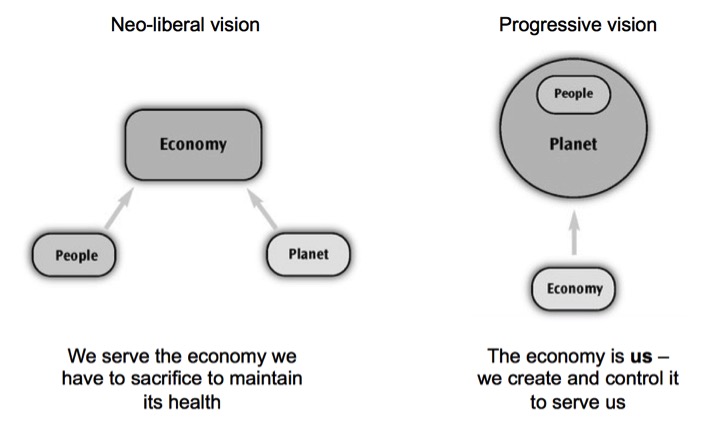

This is Part 2 of my discussion of how a progressive agenda can escape the straitjacket of neo-liberal thinking and broaden how it presents policy initiatives that have been declared taboo in the current conservative, free market Groupthink. Today, I compare and contrast the neo-liberal vision of efficiency, which is embedded in its view of the relationship between the people, the natural environment and the economy, with what I consider to be a progressive vision, which elevates our focus to Society and sees people embedded organically and necessarily within the living natural environment. It envisions an economy that is created by us, controlled by us and capable of delivering outcomes which advance the well-being of all citizens rather than being a vehicle to advance the prosperity of only a small proportion of citizens.

The progressive vision

In yesterday’s blog – Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1 – we saw that what mainstream (neo-liberal) economists deem to be ‘best’ or ‘efficient’ is heavily biased towards the fortunes of private profit seekers.

If private firms are producing for markets at the lowest cost and meeting the demands of consumers for those goods and services, then they are maximising profits and being ‘efficient’.

The textbooks all show that under certain conditions (such as, there are no monopoly forces, people are rational and have knowledge of the future and all current alternatives, firms can freely enter and exit the market, ) then free markets are the only efficient way to organise economic activity.

To prosper, the textbooks then suggest we must bend the human settlement and use the natural environment so as to allow these free markets to work in the way prescribed.

We reach perfection when we achieve this state (so that the price of each good sold is exactly equal to the extra resources that were needed to produce it).

The key assumptions made to generate this ‘perfect’ outcome never hold in the real world. Mainstream economists thus deploy the strategy that any move towards this perfect state (for example, cutting minimum wages) will be an improvement and bring the economy closer to efficiency.

They ignore literature (for example, the Theory of Second Best) which shows that if all the assumptions of the mainstream theory do not hold then trying to apply the results of the theory is likely to make things worse not better.

Almost all of the statements about ‘efficiency’ in mainstream economic theory are of this type.

Should any of these highly restrictive assumptions not hold (at any point in time), then the models cannot generate any reliable conclusions and any assertions one might make based on these economic theories are groundless – meagre ideological raving.

While the mainstream theory of efficiency does recognise the difference between private costs and benefits (borne and/or enjoyed by firms, individuals) and social costs and benefits (borne and/or enjoyed by all of us as a result of economic transactions between individuals), it rarely focuses on costs that are not quantifiable and private.

And when there are massive social costs arising from failed economic outcomes (for example, mass unemployment), mainstream economists have shown a willingness to define them away in such a way that the outcome remains consistent with their predictions.

So the example I gave yesterday was the claim that unemployment is always voluntary and therefore a product of free, maximising (and efficient) choice between income and leisure. There is a denial that the system can fail to provide enough jobs and thus render any choices that an individual might like to make powerless.

For a progressive, the essential goal of getting as much out of the inputs we muster in economic activity remains a goal. That is, this goal is shared with mainstream economists. Otherwise, there is wasteful use of human and natural resources which has no justification.

The questions though are what do we mean when we say we want to get “as much output” as we can and what the inputs that we are acknowledging?

At that point, a progressive vision of efficiency is a world apart from the narrow mainstream neo-liberal concept.

By placing Society rather than private corporations at the centre of our framework, progressives have a broader understanding of costs and benefits, which then conditions how we assess the ‘efficiency’ of an activity.

The right-side panel in the graphic above is what we call a progressive vision of the relationship between the people, the natural environment and the economy.

It leads to a solidaristic or collective approach to problems (sometimes called the All Saints approach), which has has a deep tradition in Western societies.

It recognises that an economic system can impose constraints on individuals which render them powerless. If there are not enough jobs to go around then focusing on the ascriptive characteristics of the unemployed individuals misses the point

Above all, it shifts our attention back onto Society rather than narrowing the focus to the ‘economy’ and corporations. Corporations are just one part of the economy, which is one part of the human settlement.

Once we work within this vision, our notion of efficiency becomes markedly different from that espoused within the neo-liberal vision.

Within this construction of reality, the economy is just one part of Society and it is seen as being our construction with people organically embedded and nurtured by the natural environment.

Shenkar-Osorio (2012: Location 1037) says:

This image depicts the notion that we, in close connection with and reliance upon our natural environment, are what really matters. The economy should be working on our behalf. Judgments about whether a suggested policy is positive or not should be considered in light of how that policy will promote our well-being, not how much it will increase the size of the economy.

In this view, the economy is seen as a ‘constructed object’ – that is a product of our own endeavours and policy interventions should be appraised in terms of how functional they are in relation to our broad goals.

Those broad goals are expressed in societal terms rather than in narrow ‘economics’ terms. In the neo-liberal vision, we are schooled to believe that what is good for the corporate, profit-seeking sector is good for us.

Within the progressive vision the goals are articulated in terms of advancing public well-being and maximising the potential for all citizens within the limits of environmental sustainability.

The focus shifts to one of placing our human goals at the centre of our thinking about the economy while at the same time recognising that we are embedded and dependent on the natural environment.

In this narrative, people create the economy. There is nothing natural about it.

Concepts such as the ‘natural rate of unemployment’, which suggest that governments should not interfere with the market when there is mass unemployment and leave it to its own equilibrating forces to reach its natural state, are erroneous.

Governments can always choose and sustain a particular unemployment rate. We create government as our agent to do things that we cannot easily do ourselves and we understand that the economy will only serve our common purposes if it is subjected to active oversight and control.

In the progressive vision, collective will is important because it provides the political justification for more equally sharing the costs and benefits of economic activity.

Progressives have historically argued that government has an obligation to create work if the private market fails to create enough employment. Accordingly, collective will means that our government is empowered to use net spending (deficits) to ensure there are enough jobs available for all those who want to work.

The contest between the two visions outlined in graphic was really decided during the Great Depression, which taught us that policy intervention was elemental in order to rein in the chaotic and damaging forces of greed and power that underpin the capitalist monetary system.

We learned that so-called ‘market’ signals would not deliver satisfactory levels of employment and that the system could easily come to rest and cause mass unemployment.

We learned that this malaise was brought about by a lack of spending and that the government had the spending capacity to redress these shortfalls and ensure that all those who wanted to work could do so.

From the Great Depression and responses to it we learned that the economy was a construct, not a deity, and that we could control it through fiscal and monetary policy in order to create desirable collective outcomes.

The Great Depression taught us that the economy should be understood as our creation, designed to deliver benefits to us, not an abstract entity that distributes rewards or punishments according to a moral framework.

The government is therefore not a moral arbiter but a functional entity serving our needs. Our experiences during the period of the Great Depression led to a complete rejection of neo-liberal vision.

We re-learned the lesson during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). But still the neo-liberal vision dominates. This is in no small part due to the vested interests that bankroll the media, think tanks and academics to indoctrinate the public into accepting the logic of the neo-liberal vision.

The resurgence of the free market paradigm has been accompanied by a well-crafted public campaign where framing and metaphor triumph over operational reality or theoretical superiority.

This process has been assisted by business and other anti-government interests, which have provided significant funds to emergent conservative, free market ‘think tanks’.

Sharon Beder wrote in 1999 that these institutions fine tuned “the art of ‘directed conclusions’, tailoring their studies to suit their clients or donors” (Beder, 1999: 30).

Politicians parade these so-called ‘independent’ research findings as the authority needed to justify their deregulation agendas.

Multilateral organisations such as the IMF also continue to distort policy debates with their erroneous claims and, in the case of the IMF, incompetent and error prone modelling.

[Reference: Beder, S. (1999) ‘The Intellectual Sorcery of Think Tanks’, Arena Magazine, 41, June/July, 30-32.]

How does the progressive vision expand our understanding of efficiency?

Once society becomes the objective and we recognise that people and the natural environment are the major components of attention, with the economy being a vehicle to advance societal objectives rather than maximising the lot of the profit-seeking, private corporate sector, then our conceptualisation of what is efficient and what is not changes dramatically.

This is especially the case once we understand that our national government is the agent of the people and has the fiscal and legislative capacity (as the currency-issuer) to ensure resources are allocated and used to advance general well-being irrespective of what the corporate or foreign sector might do.

It is clearly ludicrous to conclude that a society is operating efficiently when there are elevated levels of unemployment (people wanting to work who cannot find work) and where large swathes of a nation’s youth are denied access to employment, training or adequate educational opportunities.

It is inconceivable that we would consider a nation is successful if income and wealth inequality was increasing, poverty rates were rising and basic public services were degraded.

In each of these cases, the neo-liberal definition of efficiency could be satisfied, despite the overall well-being of citizens being compromised by the behaviour of the capitalist sector and the policy responses of government.

As an example, consider the case for employment guarantees as a solution to mass unemployment.

We know that the job relief programs that the various governments implemented during the Great Depression to attenuate the massive rise in unemployment were very beneficial.

At that time, it was realised that having workers locked out of the production process because there were not enough private jobs being generated was not only irrational in terms of lost income but also caused society additional problems, such as rising crime rates.

Direct job creation was a very effective way of attenuating these costs while the private sector regained its optimism.

It is well documented that sustained unemployment imposes significant economic, personal and social costs that include:

- loss of current output;

- social exclusion and the loss of freedom;

- skill loss;

- psychological harm, including increased suicide rates;

- ill health and reduced life expectancy;

- loss of motivation;

- the undermining of human relations and family life;

- racial and gender inequality; and

- loss of social values and responsibility.

Many of these ‘costs’ are difficult to quantify but clearly are substantial given qualitative evidence. Most of these ‘costs’ are ignored by the neo-liberal concept of efficiency, in part, because they accumulate outside the ‘market’ and are not quantifiable in the narrow terms of the exchange between buyers and sellers.

Most people do not consider the irretrievable nature of these losses. Every day that unemployment remains above the full employment level the economy is foregoing billions in lost output and national income that is never recovered and the unemployed individuals and their families endure the other related costs.

The magnitude of these losses and the fact that most commentators and policy makers prefer unemployment to direct job creation, shows the powerful hold that neo-liberal thinking has had on policy makers. How is it rational to tolerate these massive losses which span generations?

When direct public sector job creation is mooted as a solution, the neo-liberals chime in with their relentless claims about waste and inefficiency.

They use terms such as ‘boondoggling’ and ‘leaf-raking’ to condition our responses that these schemes just make useless work for the sake of it.

The terms ‘boondoggling’, ‘make-work’ and ‘leaf-raking’ are all synonomous and are meant to imply that nothing good comes from this type of program.

Please read my blogs – Boondoggling and leaf-raking … and The ultimate boondoggle courtesy of slack government policy – for more discussion on this point.

The same conservatives laud the virtues of the private sector as they create hundreds of thousands of low-skill, low-paid, precarious and mind-numbing jobs but hate, with an irrational passion, the idea that the public sector could employ workers that the private sector doesn’t want and get them to work on community development projects at some socially-inclusive wage.

While these free market zealots only see the massive waste of public sector job programs (because ‘the market’ didn’t create the jobs) they fail to see that:

1. National income is being produced which multiplies into more income via increased spending throughout the economy.

2. The massive loss of national income from mass unemployment are attenuated.

3. The huge intergenerational damage that entrenched unemployment to individuals, their families and the broader society is reduced.

These attacks on public sector job creation reached hysterical proportions during the Great Depression in the US, when President Roosevelt introduced his New Deal program, which included the Public Works Administration (PWA) initiative.

The facts are clear. The Public Works Administration (PWA) created hundreds of thousands of jobs and the work helped restore ageing public infrastructure (such as, roads, dams and bridges). Many new buildings were constructed during this period (schools, recreational spaces, libraries, hospitals) and have delivered benefits to the generations that followed.

There are huge reminders of the legacy of this era of public intervention by way of direct job creation. The Tennessee Valley Authority was a huge hydro-electricity project which brought electricity and prosperity to some of the poorest rural areas of the US.

As Harry Kelber wrote in 2008, at the time, the private electricity providers stridently opposed the challenge to their monopoly control. The upshot was that the project forced them to reduce their power charges.

In general, the dynamism of the public sector at that time caused huge outcries from the capitalists who didn’t want challenges to their cosy profit making industries from public sector enterprise.

The capitalists lost out to society! It is a repeating lesson that progressives seem to have forgot.

There are many examples of how job creation programs around the World have left a positive legacy while attenuating the immediate damage of mass unemployment

[Reference: Kelber, H. (2008) ‘How the New Deal Created Millions of Jobs

To Lift the American People from Depression ‘, The Labor Educator, May 9, 2008. LINK.]

Thus, when evaluating whether job creation programs are ‘efficient’ we have to consider the benefits for the workers and their families of having a job both in income terms and in the broader socio-psychological terms.

We have to consider the reduction in the intergenerational costs of children growing up in households where the parents work. We know from research that the disadvantage of unemployed parents is passed onto to their children, which means the costs of the lack of jobs extends well beyond the immediate period.

We have to consider the benefits of social stability where all citizens have access to work and income security. And many more factors that are ignored by the neo-liberal vision and its concept of efficiency.

The same sort of evaluation would be relevant when assessing whether re-nationalisation was a worthwhile strategy for a progressive government to take.

The old hoary that the conservatives raise that these industries were havens of ‘inefficiency’ always ignore the benefits of workers having secure employment and their families enjoying stable incomes. They always ignore the other pathologies that accompany mass unemployment.

And as we will see when I write the second part on the benefits of nationalisation, these conservative attacks on re-nationaisation also ignore a range of progressive benefits of having key sectors like energy, banking and transport in public ownership.

For example, it is much easier for a government to deal with climate change if it owns the energy companies. Technology shifts are much more efficient in this context. More about which later.

We noted in yesterday’s blog that the mainstream vision measures success in terms of GDP. Higher growth is deemed good and vice versa.

However, GDP is a flawed measure of societal or community well being and it largely ignores issues relating to environmental sustainability.

Instead of measuring success, for example, using GDP, progressives will seek to use other measures which capture essential characteristics of Society that are define its health.

Such measures as the Index of Social Health (ISH) (which includes indicators of child poverty, child abuse, infant mortality, unemployment, wages, health insurance coverage, teen suicide rates, teen drug abuse, high school dropouts, old age poverty, crime rates, food insecurity, housing, and income inequality) provide a broader index of social well-being.

Other measures such as the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) also provides a broader measure of the state of the nation and the role the economy is playing in advancing social and environmental well-being.

The GPI, in particular, attempts to estimate the long-term environmental damage that our economic settlement creates.

A similar approach is taken by the Gross Sustainable Development Product (GSDP) measure.

The United Nations Human Development Index (UNHDI) “was created to emphasize that people and their capabilities should be the ultimate criteria for assessing the development of a country, not economic growth alone.”

Once again, the focus of our attention is on Society, community and environment. The economy serves us not the other way around.

Conclusion

In an interview with the American radio service – PBS – on October 17, 2000, British Labour politician Tony Benn was asked whether the Great Depression led to a “huge loss of faith in markets and governments”, to which he replied:

Well, before the Great Depression, the gamblers ran capitalism and brought the economies down. And what happened? The war followed the Great Depression. In war you mobilize everything. Governments tore down the railings in Britain and America to make bullets. They rationed food, they conscripted people, and they sent them to die. The state took over. And after the war people said, “If you can plan for war, why can’t you plan for peace?” When I was 17, I had a letter from the government saying, “Dear Mr. Benn, will you turn up when you’re 17 1/2? We’ll give you free food, free clothes, free training, free accommodation, and two shillings, ten pence a day to just kill Germans.” People said, well, if you can have full employment to kill people, why in God’s name couldn’t you have full employment and good schools, good hospitals, good houses? And the answer was that you can’t do it if you allow profit to take precedent over people. And that was the basis of the New Deal in America and of the postwar Labor government in Great Britain and so on.

This is clearly is a compelling basis for a progressive narrative which does not see the economy as a separable, natural entity from the people and the natural environment.

Collective will is important because it provides the political justification for sharing the costs and benefits of economic activity more generally.

The neo-liberals hate collective will because they desire the powers of the state to be exercised to their own advantage.

There is a further dimension to efficiency that progressives need to come to terms with.

I deal with it in this blog – If you can have full employment killing Germans ….

I won’t write more about it here but a discussion of the issues that arise will appear in our final manuscript.

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

28. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost.

29. The metamorphosis of the IMF as a neo-liberal attack dog.

30. The Wall Street-US Treasury Complex.

31. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976.

32. British Left reject fiscal strategy – speculation mounts, March 1976.

33. The US government view of the 1976 sterling crisis.

34. Iceland proves the nation state is alive and well.

35. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976.

36. The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976.

37. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality.

38. The British Left is usurped and IMF austerity begins 1976.

39. Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy.

40. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation.

41. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1.

42. Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 2.

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“They use terms such as ‘boondoggling’ and ‘leaf-raking’ to condition our responses that these schemes just make useless work for the sake of it.”

You can add another one to that list: “Trident Renewal”.

Dear Bill

Isn’t efficiency ultimately something purely relative, about means rather than ends? An extermination camp can be run efficiently and a hospital can be run inefficiently. According to a value-free definition, efficiency is a low input/output ratio, or a high output/input ratio. If Peter can produce 100 widgets with 50 units of input while Paul produces the same widgets with 60 units of input, then Peter is more efficient than Paul. If Paula can type 300 words in a certain time while Sheila can type only 200 words in that time with the same typewriter, then Paula is more efficient than Sheila.

Efficiency shouldn’t be confused with productivity. If Peter plows with a big tractor and a 6-share plow while Paul plows with a small tractor and a 3-share plow, then Peter will be more productive, but he isn’t necessarily more efficient because he has more capital input.

Efficiency isn’t necessarily desirable. If a letter carrier can deliver more mail in an hour than another because he runs, then it may not desirable because he may prefer walking to running. Efficiency shouldn’t be obtained at the cost of the well-being of workers. Many hands make light work, and light work may be more pleasant than hard work.

Regards. James

Bill, here is a relevant blog which appeared today in Social Europe by Dani Rodrik. It is relevant to many of your recent blogs more so than this particular one;

https://www.socialeurope.eu/2016/07/the-popular-revolt-against-globalization-and-the-abdication-of-the-left/

Loving your series so far professor Mitchell.

There is a conflation between efficiency and effectiveness going on the mind of most mainstream economics, and even the general population which has been captured by its faux narrative and storytelling. Effectiveness is way more important than efficiency to achieve well functioning human societies, but liberalism (neo and non neo, from the XIX century and before) has conflated always both, deriving than from a high efficiency ratio, you will necessarily get higher social effectiveness (on the long run).

This comes from a very narrow understanding of what is a well functioning society, all in favour of narrow economic arguments themselves, very well described by the graphic above. All is sub-servant of the mighty “economy” God (and indirectly, the so-called “markets”). Or even a denial of such thing as ‘society’, if there is no such thing as society as neolibs claim often you can’t pursue social solutions to social problems (because neither exist), and all comes down to a newtonian machine rules by natural laws were we can squeeze a bit more efficiency, always to fight against ‘scarcity’ (real or manufactured, as neolibs love to manufacture scarcity were there is abundance, and pretend there is abundance where there is scarcity, creating chaos in the process).

The obsession with “growth” pushes this further, as if we had to constantly to push further growth, through inflating population and higher material consumption ratios. In this race we are ever chasing higher efficiency ratios, but the dangers come from the non-understanding by economists and politicians of the impossibility of maintaining exponential growth function in a real world were our knowledge and technology won’t be able to keep up with such growth.

Thereby ‘efficiency’ is not the answer to all social problems, because increased throughput as a solution to everything is a chimera that can’t be real. The other angle is to look it from the ‘efficacy’ point of view, how effective is our society at solving problems: how healthy is our population? how can we increase the mean happiness of the population and reduce conflicts, drug abuse, etc.? The answer to most complex social problems is almost never “just be more efficient!!!”, at least not in the narrow sense of value-free definition of efficiency; in fact many times it takes redundancy and “waste” to solve problems. Organisms are not Newtonian machines, at least not in a very limited understanding of what Newtonian means; societies are more like organisms, not like predictive clocks.

There is a cost structure efficiency advantage to public ownership for utilities and rail. These essential services which lower the cost of living and doing business can be ran at prices to the public at full cost of all the necessary factors of production. This cost efficiency makes the rest of the economy wealthier. The current Private (ironically still state subsidised system) has increased fares to pay off dividends for wealthy domestic shareholders and foreign owners. With public ownership the cost structure to society is lower as any profits/surplus can be immediately reinvested into those services to improve and/or expand performance and productivity. Also the fare/usages prices can be at the cost of production /service provision instead of having to price-in premiums/profits mark ups to pay off foreign dividend recipients. This lowers the cost of living for the general public; leaving them with more disposable income. This can increase consumption and distributed purchasing power which supports aggregate demand.

Public ownership has a more efficient cost structure. Which increases the wealth of the rest of the economy/society. An add on effect of this is that it makes the economy more competitive abroad, as the cost of living and doing business is lower.

This is especially true for natural monopolies like network based services and infrastructure such as rail track or electricity transistors or domestic utilities.

Public ownership has a role in the supply side which could lower the cost of business and living-(which in turn would make the economy more competitive).Local, regional or even national government could get directly involved in electricity production to increase available supply of electricity which could lower prices in the market. This would reduce the cost structure for businesses, particularly energy intensive ones, and households. Which increases profits for energy intensive firms and increase disposable income for households.

Public ownership improves the cost structure in the economy through cost efficiencies. Which will lower the costs for households and doing business. Increasing wealth and maintaining distributed purchasing power cross the population.

Public ownership can also meet macro -economic supply side challenges through cost efficient provision of output which can increase supply and bring down prices in a market otherwise dominated by a privately owned cartel

The only things neoliberalism produces efficiently are negative social impacts.

While we’re at it, Australia needs to replace the Productivity Commission with a Quality of Life Commission.