I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

I have been going back through my snippets library looking at what economists and politicians said back earlier in the crisis and comparing the predictions with reality to try to understand better why Europe is lagging behind. I have been compiling national profiles for various nations lately to ensure I remain cogniscant of the detailed developments that have been occurring. It takes some organisation. I have been concentrating by interest on Finland, Spain and Portugal lately. It astounds me when I read or hear that the Eurozone has been a success because the currency is stable. Even that last statement is false given the monetary union is fighting deflation at present with recessed output levels and entrenched mass unemployment. The current statements coming out of European leaders accord almost directly with the same sort of things they were saying in 2010 as the region was plunging deep into recession. It seems that they have learned nothing. Some of the past leaders have retired with handsome pensions and will not be held to account for their policy incompetence. Others remain in office and their public statements demonstrate that they cannot see beyond the blindness of the Groupthink that defines the patterned behaviour of the elite European policy-making institutions.

In the lead up to the Toronto G-20 Summit in June 2010, the Der Spiegel article (June 25, 2010) – Germany Warns US Not to Become ‘Addicted to Borrowing’ – reported that the US representatives had argued “that Germany abandon austerity in favor of additional economic stimulus measures”.

It quoted German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble as saying:

… governments should not become addicted to borrowing as a quick fix to stimulate demand. Deficit spending cannot become a permanent state of affairs … while US policymakers like to focus on short-term corrective measures, we take the longer view and are, therefore, more preoccupied with the implications of excessive deficits and the dangers of high inflation.

Schäuble predicted that the US policy position would trigger a disastrous inflationary spiral.

On June 16, 2010, the then boss of the ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet gave an – Interview with La Repubblica – the Italian newspaper.

He reiterated the Ricardian Equivalence nonsense claiming that by cutting into fiscal deficits the Eurozone leaders would “increase the confidence of households, investors and firms and, therefore, consolidate the recovery.”

The evidence base tells us he was fundamentally wrong. Private investment continued to collapse and consumption expenditure remained subdued as fiscal austerity was imposed.

Trichet was asked whether the policy response in the Eurozone at the time (austerity) posed a “clear risk of deflation”. He replied:

I don’t think that such risks could materialise. On the contrary, inflation expectations are remarkably well anchored in line with our definition – less than 2%, close to 2% – and have remained so during the recent crisis. As regards the economy, the idea that austerity measures could trigger stagnation is incorrect.

Wrong – very wrong – completely wrong.

Austerity caused the stagnation and the Eurozone remains locked into a struggle with deflation and stagnant economic growth which is not being driven by capital formation, thus underpinning growth in potential GDP as well as supporting current spending.

I re-read a German article in Der Spiegel from November 2010 – Germany Blasts Bernanke: Results of Fed Stimulus Could Be ‘Horrendous’ – which quoted the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble as saying:

They have already pumped an endless amount of money into the economy via taking on extremely high public debt and through a Fed policy that has already pumped a lot of money into the economy. The results are horrendous …

Der Spiegel also quoted the then European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso who told the G-20 media circus that:

… there is no more room for deficit spending.

Let’s have a little reflection on the “results”.

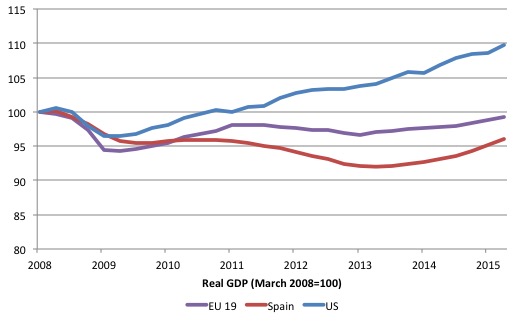

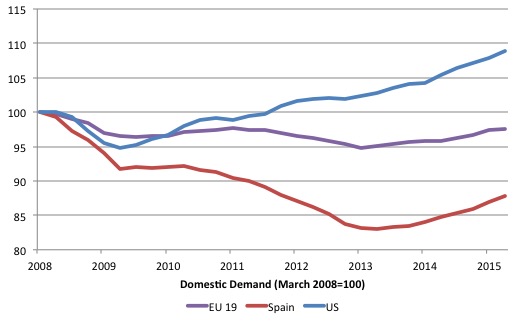

Consider the following graphs. The first shows the evolution of real GDP indexed to 100 at March 2008 for the Eurozone nations, Spain (individually) and the US up to the June-quarter 2015. The second shows the evolution of real domestic demand (Total private consumption and investment, and Total government spending), similarly indexed for the same entities.

The initial downturn was similar in speed and ferocity for all three cases but that is where the similarity ends. The early fiscal stimulus in Europe (driven by both some discretionary measures and the operation of the automatic stabilisers) saw some positive growth response.

But that was curtailed fairly quickly once the SGP rules were asserted (more or less) and fiscal austerity was prioritised. After 7.5 years, the 19 Eurozone Member States together are still not back to the March 2008 peak – so as a bloc the real output losses continue to accumulate as the world approaches the next cycle.

For Spain, real GDP is still 3.9 per cent below the March 2008 peak and despite all the hype about it being the ‘poster child’ for austerity that 7.5 year outcome does not look very successful to me. I will have more to say about Spain another day as I compile other information.

There are many indicators that suggest the Spanish recovery is weak, reliant on low-wage precarious jobs and has not been driven by high productivity-inducing investment. Stay tuned for an ugly downturn when the next cycle turns.

The standout in this company, is, of course, the US even though by any standards its recovery has been pretty weak. For example, between the March-quarter 2000 and the March-quarter 2008, the US grew by 21.3 per cent overall.

Between the March-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2008, the US economy grew by 9.7 per cent. But relative to Spain and the Eurozone as a whole, the US performance is excellent.

Then consider domestic demand. The US has experienced an 8.8 per cent growth in domestic demand between the March-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2015 whereas for the Eurozone, domestic demand has contracted by 2.5 per cent and for Spain it has contracted by a massive 12.2 per cent.

The components of domestic demand are also interesting.

Between the March-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2015, total consumption grew by 7.9 per cent while private investment (capital formation) grew by 13.8 per cent.

Over the same period, total consumption in the Eurozone grew by 1.5 per cent while total investment fell by 15.3 per cent. For Spain, consumption expenditure fell by 5 per cent and investment fell by 30.9 per cent.

The dramatic drop in capital formation in the Eurozone (and particularly in Spain) has not only suppressed real GDP growth over the period shown but will also mean that future growth rates will be reduced because potential output growth has slowed and those effects will endure for many years at least.

With the massive drop in domestic demand in Spain one could hardly hold it out as a poster child for the policy stance that was forced onto the citizens there.

One might suggest that the dominant Eurozone policy stance which emphasises fiscal austerity and export-led, internal devaluation has been inferior to the US growth strategy which has relied on continued fiscal deficits supporting a recovery in domestic demand.

I know there are some who argue that the major difference between Europe and the US has been monetary policy – given the Eurozone has only engaged in large-scale quantitative easing recently.

But as context, Japan and the UK have had inferior performance to the US but better than the Eurozone – both engaged in quantitative easing throughout the crisis.

By contrast, Australia brought in a relatively large discretionary fiscal stimulus early in the crisis and, like the US, has maintained the fiscal deficit, despite the conservative intention to cut it. The Reserve Bank of Australia did not engage in quantitative easing. The outcomes have been vastly superior to Europe. Real GDP has grown by 18 per cent between the March-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2015 and domestic demand has risen by 16 per cent.

Now think about the current policy persuasion in Europe at present.

On fiscal policy, the Eurozone is still hell-bent on imposing austerity under their Stability and Growth Pact and related additions since the crisis (six- and two-packs and the fiscal compact).

The UK Guardian article (October 15, 2015) – Italy budget: Renzi risks Brussels battle – reports that plans by the Italian government to introduce some fiscal stimulus as the nation wallows in recession will be rejected by the European Commission.

The article says that:

… a series of business-friendly tax cuts and measures to boost consumer spending … could be rejected … the Brussels elite … wants Italy to take the opportunity of its recent recovery to step up fiscal tightening.

Extraordinarily, it appears that the European Commission:

… is concerned that the deterioration in world trade following the slowdown in China could hurt the Italian economy, hitting tax revenues and further widening the budget deficit.

So they have learned nothing from the crisis. The application of the fiscal rules requires nations to impose discretionary cuts to net public spending in a recession because the operation of the automatic stabilisers (lost tax revenue due to slower growth) push the recorded fiscal deficit beyond the 3 per cent ceiling.

The correct response to a decline in the external contribution to total spending and real GDP is to expand domestic demand. If private sector consumption and investment growth is insufficient to make upt he lost spending then the government sector has to be the source of spending.

The Eurozone adopts the perverse strategy, which is not specified in any economics textbook, mainstream or otherwise – that when total private spending is falling, net public spending also has to fall.

The performance of their economy shown in the graphs above demonstrate how ridiculous that policy stance is.

Of course, the fiscal outcome is sensitive to major downturns in the external economy. But that is the very reason that discretionary net public spending should increase as tax revenue is falling due to the slowdown in the private economy.

There was an article in the Financial Times (October 5, 2015) – What the bankers can teach stimulus-addicted economists – by one Ludger Schuknecht which is instructive.

Who is Ludger Schuknecht? He is the “chief economist of the German finance ministry” or in other words the right-hand person for the Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble.

He constructs fiscal stimulus as a drug addiction and that is why “so many economists keep asking for more”.

This is metaphorical language designed to disabuse people of the notion that responsible use of fiscal policy usually requires continuous fiscal deficits.

He claimed that:

… after decades of attempts to fine-tune the economic cycle by running fiscal deficits and cutting interest rates at times of weak demand, many economies are fragile. In too many countries debt and public spending are high, and interest rates close to zero. This leaves little room for effective policy when the next crisis hits – as it surely will.

First, the claim that the history of fiscal and monetary policy and the current ‘fragility’ of “many economies” now is intended to be causal but is, of course, spurious.

For decades, nations ran continuous fiscal deficits of various magnitudes and adjusted interest rates and discretionary public spending up and down according to movements in the non-government spending cycle.

These nations enjoyed growing living standards driven by real wages growth in line with productivity growth and full employment. Real GDP growth was much stronger than it has been in the era of fiscal austerity.

Everything wasn’t perfect and there was instability as a result of the fixed exchange rate system under the Bretton Woods agreement, particularly in Europe.

But the fragility we see now in many economies is a direct result of the neo-liberal era which has downplayed the use of fiscal deficits, promoted monetary policy as an inflation-first policy tool and introduced widespread financial deregulation that unleashed the greed and irrationality of the investment banks.

Second, there is no less “room for effective policy now” should governments wish to use their spending capacity. The “room” is artificially restricted in the Eurozone by the fiscal rules. But in currency-issuing nations the national government can purchase any unsold goods and services that are available for sale in the currency of issue – including any unemployed labour.

The “room for effective policy” is thus defined by the idle real resources that the government might wish to bring back into productive use.

It is ridiculous to claim otherwise.

The Financial Times article gives you a window into the mentality of the German government. We read that Ricardian Equivalence is alive and well in the Finance Ministry:

Consumers and businesses are more confident in their economic prospects when they believe governments and central banks can respond to challenges.

Which he intends to mean that if governments cut their discretionary fiscal deficits and increase interest rates then the non-government sector will spend up big.

Pigs might fly! And it won’t be those Eurozone PIIGS!

Apparently, “this lesson goes largely unheeded”. No it hasn’t! The Eurozone has basically followed a policy stance similar to this and things have deteriorated further. We have the experiment – it has failed.

Conclusion

There is only one reasonable way to interpret the graphs produced above.

My current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – is about the patterned behaviour in Europe which has led to a major denial of the facts among the Eurozone elite.

I think the title is still current.

Advertising: Special Discount available for my book to my blog readers

My new book – Eurozone Dystopia – Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – is now published by Edward Elgar UK and available for sale.

I am able to offer a Special 35 per cent discount to readers to reduce the price of the Hard Back version of the book.

Please go to the – Elgar on-line shop and use the Discount Code VIP35.

Some relevant links to further information and availability:

1. Edward Elgar Catalogue Page

2. Chapter 1 – for free.

3. Hard Back format – at Edward Elgar’s On-line Shop.

4. eBook format – at Google’s Store.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill Mitchell, thank you for your visit to Finland – it has been inspiring. I finished part III of your book now 🙂

The article of Schuknecht is interesting, as Finnish ex-PM and current finance minister Alexander Stubb also compared government borrowing to doping.

I recently wrote a blog post for the Eurocrisis in the Media -blog on Finland, which no doubt also reflects your own recent experience. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/eurocrisispress/2015/10/08/finnish-competitiveness-raising-policies-and-their-discontents/#more-4701

Best, Paul Jonker-Hoffrén

Because there is nothing to learn. The walls of the cave are the ends of the Universe. There is a currency inside the cave, but no one sees it is also the key to a greater Outside. It takes a particular type of intelligence to do that, and the cave dwellers, viewing those who could do so as other societies had once viewed left-handers, have carefully exorcised them from the bloodline of the their own, until even the memory of them has faded into the dull chiaroscuro of a sleep without dreams. There is happiness in the cave, but only for the learned ones, and that is fine, because that is all that is possible.

BTW this just appeared in my blog stream – sits well (in part) with your post:

http://bruegel.org/2015/10/clueless-in-europe/

Bill,

I couldn’t agree more with your analysis.

I am providing a link to the infamous blackmail letter that Trichet sent Zapatero in 2010.

http://estaticos.elperiodico.com/resources/pdf/7/1/1385549200917.pdf

The letter effectively killed of the expansionist fiscal policy that brought the fiscal deficit to 9% of GDP and was begining to produce a recovery. The letter is essentially a neoliberal agenda imposing deregulation of the labor market to undermine the bargaining capacity of workers, reduces serverance payments, kills collective bargaining and sundry “free market” reforms. It is also an extralimitation of the former ECB beyond his powers which makes equivalent to a coup d’êtat. After the intervention of ECB Spain plunged into an even worse depression and deflation from which we are barely inching out now after causing misery and pain and turning Spain into the most unequal country in Western Europe.

If you need help in accessng statistical data for your article in Spain just holler.

Best,

Stuart

Gdp is a inherently false metric to use ( it’s merely a measure of pointless activity)

Spain is a deadzone, a victim stark victim of the money monopolists and their elephant like memories.

Dig deeper (net national income) and you will begin to realise the economic crisis is in reality european civilizational collapse.

Rise of activity (not wealth) in Spain a result of increased touristic (exporting of wealth) in return for tokens from the company store.

Touristic activity increase a simple result of the implosion in North Africa.

“Between the March-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2008, the US economy grew by 9.7 per cent. But relative to Spain and the Eurozone as a whole, the US performance is excellent.”

Is this correct?

“Between the March-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2015, total consumption grew by 7.9 per cent while private investment (capital formation) grew by 13.8 per cent.”

According to W. Mosley it was investment in the ‘oil industry’ that prevented the economy from contracting/not expanding due to tax increases and sequestration?

Bill, Have secured in e-format your new book ‘Groupthink’ and I am enjoying the read. Very comprehensive history of the European predicament and great analysis. Looking forward to the last few chapters as they appear to be quite interesting.

Has Corbynomics been borrowed from MMT thinking, because that’s what it appears to be?