In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Corporate welfare is rife in Japan’s banking sector

I am travelling a lot today so I am typing this up in between segments. I met a journalist in Tokyo on Friday and we discussed various matters relating to the current policy debate in Japan. In addition, we discussed the latest situation for the Japanese banking sector and the fact that they are recording record levels of net profits almost across the board, but particularly for the three mega banks, and it might surprise readers when they learn the source of those profits. It is actually quite scandalous but demonstrates the bind that the Bank of Japan now finds itself in – of its own doing, while being cheered on by mainstream economists, several of which are probably receiving lucrative consulting income from the very same banks.

Complementary Deposit Facility

The – Complementary Deposit Facility – is the fancy name process by which the Bank of Japan pays the commercial banks an interest return on excess reserves held by the banks at the central bank.

Further information is available from the BOJ – What is the Complementary Deposit Facility?

CABs are just the “current account balances” that the banks hold with the BOJ as part of the clearing system and “special reserve account balances”.

Each “Designated Reserve Maintenance Period” or “DRMP”, the BOJ calculates the interest payments it gives the commercial banks (simply “multiplying aggregated excess reserve balances” by the current agreed interest rate),

Essentially the BOJ calculates “Aggregated excess reserve balances” as the “sum of the amount of CABs each day during the DRMP less the … the amount of required reserve per day” and provides the commercial banks with a competitive return on those excess balances.

On January 27, 2025, the Bank of Japan increased the interest rate on their Complimentary Deposit Facility from 0.25 to 0.5 per cent.

It introduced this scheme in its monetary policy statement issued on October 31, 2008 – On Monetary Policy Decisions (Change in the Guideline for Money Market Operations, Announced at 1:58pm).

It said the scheme had been decided by “unanimous vote”:

To ensure stability in money markets, a temporary measure will be introduced to pay interest on excess reserve balances in order to further facilitate the provisioning of sufficient liquidity toward the year-end and the fiscal year-end. This measure will be effective from the November reserve maintenance period to the March 2009 reserve maintenance period, and the interest rate applied will be 0.1 percent …

Of course, it was not a temporary measure.

Why did it do this?

Therein lies the bind I mentioned in the Introduction.

In Attachment 2 of the previously linked BOJ statement (above), the bank explains its motives for introducing the Complementary Deposit Facility.

The pressures on the financial system that the GFC engendered led central banks to ramp up their purchases of government bonds in the secondary markets as a way of driving down yields on the bonds (increased central bank demand drove the price of the fixed income assets up and the yields down).

The manifestation of this in the banking sector was the massive build up of excess reserves – the banks were flooded with liquidity – far in excess of the levels they required to meet the daily demands of the clearing system.

The BOJ then faced a dilemma which they noted in the Attachment 2:

Provisioning of sufficient liquidity, however, may induce the uncollateralized overnight call rate (the policy interest rate) to sharply fall below its targeted level.

The point, which only Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists have ever really noted among academic economists, is that if the excess reserve balances receive no return, then the commercial banks which hold the excess balances will try to get rid of them in the overnight market (the market where financial institutions trade among themselves) to banks that might be short of reserves.

This is a competitive process and in trying to get rid of the excess reserves the banks effectively drive the overnight rate down towards zero – any return is better than zero if zero is the default result of doing nothing.

The problem for the BOJ is that if it wanted to run a non-zero policy rate then this inter-bank competition will compromise that policy objective.

The solution for the BOJ is to either soak up the excess reserves by selling government bonds which generate a competitive yield to the banks or to simply offer a competitive yield on the excess reserves and leave the balances intact.

Clearly, the first option is not viable if the reason the excess reserves emerged was because the BOJ was buying up bonds.

So the BOJ opted, as most central banks did, for the second option – and hence the Complementary Deposit Facility was created.

At the time (October 2008), the BOJ’s target policy rate was 0.3 per cent and it paid 0.1 on the excess reserve balances (20 basis points below).

There have been many changes to this “temporary measure” since its introduction.

On March 2011, the rate on excess reserves was reduced to zero, in accordance with further policy rate cuts.

On January 2016, a new multi-tiered system was introduced in line with the announcement of the Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) with Negative Interest Rate policy.

The BOJ’s explanation (What is the Complementary Deposit Facility?) was that:

Under the framework of QQE with a Negative Interest Rate, current accounts at the Bank were divided into three tiers, to which a positive interest rate, a zero interest rate, and a negative interest rate were applied, respectively.

The three tiers were:

1. “Basic Balance: a positive interest rate of 0.1 percent will be applied”.

2. “Macro Add-on Balance: a zero interest rate will be applied” – this component comprised required reserves and balances accumulated as part of the BOJ loan program associated with the “Great East Japan Earthquake”.

3. “Policy-Rate Balance: a negative interest rate of minus 0.1 percent will be applied” – the difference between total balances and the sum of 1 and 2.

This system was explained more fully in the BOJ statement issued on January 29, 2016 – Introduction of “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with a Negative Interest Rate”.

The negative interest rate policy was abandoned in March 2024 and abolished the tiered system applied to the Complementary Deposit Facility.

It then reverted to paying a positive interest rate on excess reserves (the policy that had applied before 2016).

I discussed some aspects of these changes in this blog post – There will not be a fiscal crisis in Japan (June 23, 2025).

In a Speech at the 2025 Spring Annual Meeting of the Japan Society of Monetary Economics – The Bank of Japan from the Perspective of Business Operations – the BOJ Deputy Governor explained very clearly what was going on.

He said that the policy of paying interest on excess reserves has meant:

… it has become possible for a central bank to determine the size of its balance sheet separately from the guidance of interest rates, thereby enabling it to implement large-scale policies using the asset side of its balance sheet.

So the BOJ can buy as much government debt as it chooses without compromising its policy interest rate – and does that by leaving the excess reserves in the system and cutting off any “arbitrage” that would see rates drop to zero by paying a competitive return on the excess reserves.

Current balances and income flows

As at November 20, 2025, the total current account balances subject to the Complementary Deposit Facilty stood at 488,780 billion yen (Source).

Some simple arithmetic tells us that the total payments under the CDF are around 0.38 per cent of the September-quarter nominal GDP or around 2,443.9 billion yen.

In effect, the BOJ is now paying out massive amounts to the commercial banks, which surprise-surprise, underwrites their record level of profits.

Profitability of Japanese Banks

The BOJ publishes 6-monthly reports on the banking sector, the latest being the – Financial System Report (October 2025) (published October 23, 2025).

Also, the Financial System Report Annex Series provides more detail.

Financial Results of Japan’s Banks for Fiscal 2024 (published September 12, 2025) – provides interesting information about the profitability of the banks.

We read:

At major financial groups, net income for fiscal 2024 was about 4.5 trillion yen, increasing by 33.2

percent from the previous year. Net income was boosted by an increase in net interest income

following rises in yen interest rates and domestic loans outstanding …At major banks (on a non-consolidated basis), net income for fiscal 2024 was about 3.3 trillion yen,

increasing by 47.5 percent from the previous year, despite a marginal decrease in net non-interest

income.

So those who doubt that higher interest rates provide benefits to commercial banks should reflect on their position.

This is one of the reasons that bank economists around the world are always demanding the central banks increase rates – they know full well that bank profits increase as a result.

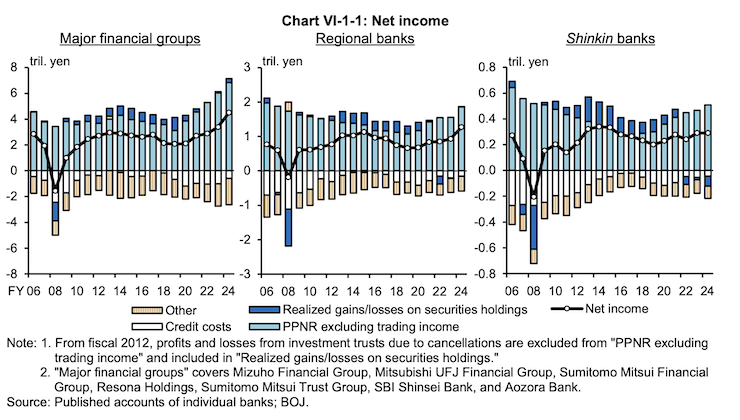

The following graph is taken from the BOJ’s Financial System Report October 2025 (cited above) (page 71) and shows the net income for the major banks, the regional banks and the Shinkin banks in Japan.

Shinkin banks are a Japanese creation and are local membership cooperatives that serve local SMEs – they are sort of akin to building societies in Australia.

Data I was provided with that comes from a financial services company in Tokyo shows that:

1. The average net income for the largest 16 banks rose by 16.7 per cent (annual basis) in the first half of 2025.

2. Net income for the three mega banks rose – 12.7 per cent for MUFG (Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group); 27.6 per cent for Mizuho FG; and 27.3 per cent for SMFG (Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group) – they have recorded record net profits.

3. The next tier of banks (Yokohama Financial Group, Mebuki Financial Group, Gunma Bank, Kyoto Financial Group, Iyogin Financial Group, and Daishi Hokuetsu Financial Group) all expect net profit increases exceeding 20 per cent.

4. The Total net income for the top 16 banks was 4,994 billion yen evaluated in quarter three.

5. The vast majority of the banks are forecasting further increases in their net income into fiscal year 2026.

Compare that to the total income received from the BOJ as a result of the Complementary Deposit Facility – 2,443.9 billion yen.

Almost half – although the lack of data prevents us from attributing the latter to the former in any direct way.

But it is fair to say that a significant proportion of the lift in net income that the Japanese banks are enjoying in 2025 has come from the interest payments that the Bank of Japan is providing on excess reserves.

In other words, a significant flow of profits is coming from the ‘government’ payments while the commercial banks do nothing to earn it nor take any risk in earning it.

Annual dividends paid by the banks are also rising which means the payments under the Complementary Deposit Facility are enriching the shareholders of the banks, while ordinary consumers are being hit with higher borrowing rates.

It is forecast that if the BOJ was to increase its policy rate by a further 0.25 per cent, the banks would record a further 300 billion yen in annual profits.

Now consider this …

We often hear statements relating to income support payments to the unemployed – that the jobless citizens have become welfare dependent.

Proponents of this view also insist that the unemployed are forced to jump through an array of compliance hoops (euphemistically labelled ‘activity tests’ but are mostly socio-pathological punishment regimes) in order to get the pittance governments give them.

But you will find nothing written in the financial press about the massive corporate welfare scheme operating across the world’s financial sectors whereupon the governments via their central banks are paying out billions to commercial banks via these excess reserve payments, which are underwriting their net profits and boosting the wealth of the bank’s shareholders.

And the banks do not have to do anything in order to get the ‘corporate welfare’.

That is why I said it was scandalous in the Introduction.

Conclusion

The MMT perspective is clear – the central bank should set the policy rate at zero and not offer a return on excess reserves within the banking sector.

My own position goes further than that and it involves nationalising all the banks.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The solution for the BOJ is to either soak up the excess reserves by selling government bonds which generate a competitive yield to the banks or to simply offer a competitive yield on the excess reserves and leave the balances intact.”

Or introduce Minimum Reserve Requirements (MRR) as the ECB has done to put in a ‘false floor’ with a zero rate tier. An idea that is the latest sticking plaster on a failing concept, even if they have only introduced a very small tier at present.

All without any consideration that if interest rates ‘work’ with an MRR in place, then there is no reason why the central bank can’t “QE” the whole stock of bonds and then increase the MRR accordingly. After all why hand out any free money if even the latest neoliberal ‘inflation targeting’ models say they don’t have to.