I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

IMF recommends that firms should increase real wage growth in Japan

I read two articles/reports today about Japan. The first was a Fairfax article (March 21, 2016) from a journalist who invariably peddles the neoliberal economic myths. The second was from the IMF extolling the virtues of higher wages in Japan. What? Yes, you read the second point correctly. The IMF considers that an essential new policy element (a “fourth arrow”) is required in Japan in the form of real wages growth outstripping productivity growth by around 2 per cent. It wants the government to legislate to ensure that happens. In general, the IMF solution for Japan is in fact one of the key changes that nations have to do bring in to restore some sense of stability into the world economy. Governments around the world has to ensure that real wages growth, at least, keeps pace with productivity growth and that workers can fund their consumption expenditure from their earnings rather than relying on ever increasing levels of credit and indebtedness. This will of course require a fundamental change in our approach to the interaction between society and economy. It will require increased employment protection, larger public sector employment proportions, decreased casualisation, and legislative requirements imposed upon firms to pass on productivity gains. It’s no small order, but it is one of a number of essential changes that we will have to do introduce as part of the abandonment of neoliberalism.

The Fairfax article – Why banks may start dropping money from the sky – recounted some personal experiences of the recent decision by the Bank of Japan to impose negative interest rates on commercial bank reserves.

That part of the article is relatively uninteresting and entirely predictable. The commercial banks are now passing on the central bank ‘tax’ to their customers and it appears people are becoming annoyed at being charged to withdraw their own money.

If people really wanted to spend their savings then they would already be doing that.

Please read my blogs – The folly of negative interest rates on bank reserves and The ECB could stand on its head and not have much impact – for more discussion on this point.

But as the article progressed, the spin escalated.

We read that:

The world is running out of interest-rate tricks to stimulate growth. And government spending is a dead end too. Since the global financial crisis, combined government and private debt globally has blown out from $US142 trillion to more than $US200 trillion. Most will never be repaid.

Tricks with interest rates and government deficits are vital short-term tools to keep economies from slumping into recession or worse. But they do not generate growth in the longer run.

I agree that attempting to manipulate interest rates as a counter-stabilisation measure (that is to influence economic growth in either direction) is a relatively ineffective policy strategy.

The overall outcome of interest-rate changes is somewhat ambiguous and is certainly indirect and untargeted.

But the oft-repeated claim that “government spending is a dead end too” is plainly wrong.

What do you think would happen if the government in any nation announced that they would employ anybody who wanted to work and that such people should simply turn up at some designated address to commence their jobs? I predict millions of people around the world who are currently wallowing in unemployment would immediately take up the offer and start earning income and spending it.

What do you think would happen if the government in any nation announced that they were intending to improve public transport, improve the hospital system, improve the education system, and engage in large-scale environmental restoration projects? How much non-government interest would you expect there to be in the subsequent public tenders to provide capital and labour services to support this strategy? I predict there would be substantial interest among firms who currently have idle capital and poor sales outlooks.

We could give any number of examples where government spending would immediately stimulate non-government sector activity and bring idle productive resources back into use.

The characters who make these claims that “government spending is a dead-end” never blink when there is a public announcement about some large military contract that is just being agreed to, which commits the government to large outlays on tanks, aircraft, submarines and the like.

Further, what evidence to suggest journalist have that the government debt that has been issued since the global financial crisis “will never be repaid”. That is an extraordinary statement to make and defies any understanding of history and evidence.

It is one of those throwaway lines that these pathetic journalists used to invoke negative emotions and fear about government deficits.

The rest of the article was a beat up of trade unions in Australia, which doesn’t bear scrutiny.

IMF promotes wage rises in Japan

The second report I read about Japan was an IMF Working Paper (No. 16/20) – Wage-Price Dynamics and Structural Reforms in Japan – published on February 10, 2016.

The research evidence is that “part of the protracted downturn” in Japan is due “to insufficient fiscal stimulus” in the 1990s.

When the the property bubble burst in the early 1990s in Japan, the Japanese government ramped up public expenditure growth to maintain real GDP growth. In 1993, total tax revenue fell by 3.7 per cent and fell again in 1994 by 1.6 per cent.

Government spending growth increased by 6.4 per cent in 1993, 2.8 per cent in 1994, 4.1 per cent in 1995 and 4.8 per cent in 1996 – which was a combination of cyclical effects (automatic stabilisers) and discretionary decisions to stimulate growth.

The fiscal support that was provided allowed the Japanese economy to avoid any negative real GDP growth (on an annualised basis) despite the massive collapse in private spending after the property collapse.

That was a remarkable demonstration of the effectiveness of fiscal policy in offsetting fluctuations in private spending.

I would note that even though the fiscal deficit grew in the mid-1990s, it remains true that the Japanese government was overly cautious with respect to the provision of fiscal policy stimulus. They initially adopted an expansionary role which delivered modest real GDP growth.

But, over this period they were constantly harassed by the likes of the IMF and OECD (and the host of commentators who choose to repeat the propaganda coming out of those institutions).

We were told then that Japan was about to collapse, that bond markets would shun the government, that interest rates and inflation would surge and that the government would run out of money.

The same sort of idiot statements that are still being made today by these right-wing loons.

The problem was that the Japanese government succumbed to the ideological pressure and in 1997 introduced a sharply contractionary fiscal shift, which included sales tax increases and cutbacks in spending. Expenditure growth was cut by 0.7 per cent in 1997.

This shift was to satisfy the likes of the IMF!

The results were almost immediate and a palpable reminder that fiscal policy is effective in both directions. The economy, which was showing some signs of recovery given the fiscal support, nose-dived.

Moreover, the fiscal deficit expanded. Tax collections fell by 3.4 per cent in 1998 and a further 1.9 per cent in 1999.

It was only the application of further fiscal stimulus that saw the economy resume relatively robust growth in the early 2000s.

Please read my blogs – Japan thinks it is Greece but cannot remember 1997 and Japan returns to 1997 – idiocy rules! – for more discussion on this point.

The IMF paper summarises the so-called ‘three arrows’ of Abenomics – “aggressive monetary easing, flexible fiscal policy, and ambitious structural reforms … the first two so-called arrows of Abenomics are represented as having the aim of reflating the economy in the near term, while implementation of the third arrow would lift potential growth in the long run.”

The paper specifically seeks to examine:

… the effects of Japan’s labor-market and product-market characteristics on the country’s wage-price dynamics and hence of the role of structural factors in perpetuating the country’s economic doldrums.

It discusses the so-called “life-time employment model” and more recent developments, which include “a growing share of workers holding so-called non-regular jobs, for instance part-time positions”.

We learn that the breakdown in ‘life-time employment’ now sees around 37 per cent of the total labour force in part-time positions.

The other major development as the ‘life-time employment’ approach has declined is that there has been “a marked decline in union power”, which has interrupted “synchronized wage bargaining”.

The paper also notes that Japanese firms have a “large share of cash holdings on corporate balance sheets” and “have been reluctant to raise wages, investment or dividend payments”.

In this context, the Japanese Prime Minister has applied “moral suasion on firms to raise wages” and resolve “to raise minimum wage growth to 3 percent”, in an attempt to break the deflationary grip.

The IMF paper uses a standard New Keynesian framework, which is limited at best. For example, to make the mathematics tractable it “presents a closed-economy model where consumer-workers and firms interact in the labor market and in the product market, and the central bank pursues a price stabilizing monetary policy”.

Japan is hardly a closed economy.

I have considered the limitations of these type of models before. Please read my blog – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on this point.

A detailed critique of both the formal (mathematical) and the logical aspects of these New Keynesian equilibrium models is also presented in my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned.

So I won’t continue to eviscerate that aspect of the work. Any macroeconomist who uses the New Keynesian approach (Krugman, Simon Wren-Lewis) is wasting their brain power.

But the paper does present some interesting empirical evidence.

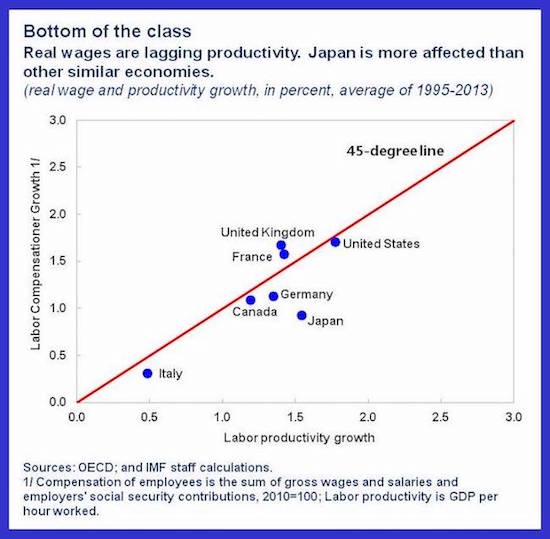

For example, we are introduced to the following graph, which shows “the empirical relationship between labor productivity growth and real

compensation growth for G7 countries” between 1995 and 2013.

The graph comes from the blog reporting on the paper – Japan: Time to Load a Fourth Arrow-Wage Increases – and is a bit different in the time period covered from the graph presented as Figure 1 in the Working Paper.

The heading on the graph says it all. The IMF paper says that:

… over the last two and a half decades productivity improvements did not lead to increases in real wages … As a consequence, the labor income share has declined markedly since the 1990s, from 66 percent in 1991 to 59 percent in 2007.

I will come back to this shortly.

As an aside, comparing the two graphs show how sensitive relationships can be to slightly different sample periods. The graph in the Working Paper (Figure 1, page 8) is for the period 1992 to 2014 and shows Canada enjoying real wages growth in excess of labour productivity growth (by a substantial margin).

The graph in this blog shows Canada crossing the 45 degree line, which means that real wages growth trailed labour productivity growth over the 1995-2013 period.

In my professional life I have actually been confronted with situations (as a referee) where the results of papers that purport to demonstrate very strong results consistent with the neoliberal paradigm of free markets collapse when extra data is added.

In one case, the authors had deliberately used a sample that was one observation less than the complete available data set (and declined to explain to their readers that they were doing this all that, in fact, there was extra data) and when I added the extra observation all of their so-called “interesting results” (that was supportive of deregulation of the labour market) disappeared. In fact, the signs on the key variables switched, which meant that the data was telling us exactly the opposite message to that claimed by the authors to be robust. It was a disgusting example of the mis-use of econometrics.

The IMF paper notes that the lagging real wages has been due to:

… anemic increases or even outright decreases in compensation for regular workers. However, the largest factor that has contributed to paltry wage growth … has been a composition effect: the share of workers who hold lower-paying non-regular positions almost doubled since 1991 to 37 percent of the workforce in 2014. This dramatic increase in duality has been the most notable development in Japan’s labor market since the 1990s.

The rise of more casual employment undermines productivity growth because “firms have a lesser incentive to train non-regular workers and the latter to exert effort in the workplace”.

The conclusion of the IMF paper is that:

… structural reforms that reduce labor-market duality, and thus improve the bargaining power of workers, may generate favorable wage-price dynamics that move the economy closer to hitting its target for inflation …

… workers’ bargaining power in Japan has been deteriorating since the early 1990s … [and] explains the fact that real wages have failed to keep up with productivity improvements and CPI inflation has hovered around zero over the last two and a half decades. On the one hand, Japan has been able to keep a low rate of unemployment despite the strong economic slowdown, but the unfavorable wage-price dynamics resulting from workers’ declining bargaining power have made price reflation even more difficult.

The related IMF blog on the paper (cited above) tells us a bit more. It concludes that:

1. “Everybody agrees: wages need to grow if Japan is to make a definite escape from deflation.”

2. “Full- time wages have increased by a mere 0.3 percent since 1995! For example, despite its record profits …”

3. “the labor market has continued to tighten and participation reached a historic high. By end 2015, only 3.3 percent of people looking for jobs were unemployed”

4. “Yet the current wage negotiations are hardly aggressive at all”.

5. “a fourth arrow needs to be loaded:

– The government could replicate the success of the corporate governance reform by introducing a “comply or explain” mechanism for profitable companies to ensure that they raise wages by at least 2 percent plus productivity growth.

– The authorities could strengthen existing tax incentives to raise wages.

– Policymakers could even go a step further by introducing tax penalties for companies not passing on excessive profit growth.

– Another option is to set the example by raising public sector wages in a forward looking manner.

I have long been arguing that one of the causes of the GFC and its extended aftermath has been the break between real wages growth and productivity growth, which was deliberately engineered by the neoliberal reforms that began in the 1970s as Monetarists took hold of the policy levers.

In the 1980s, when privatisation formed the first wave of the neo-liberal onslaught, we all apparently became “capitalists” or “shareholders”.

We were told that it was dinosauric to think in terms of the old class categories – labour and capital. We were told we now all had a stake in a system where reduced regulation and oversight would produce unimaginable wealth, even if the first manifestations of this new ‘incentivised’ economy channelled increasing shares of real income to the highest percentiles in the distribution.

We were told that “trickle-down” would spread the largesse.

We know better now – and increasingly the recognition, exemplified in 2006 by Warren Buffett’s suggestion that “There’s class warfare, all right … but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning” (Source), is that class is alive and well and in prosecuting their demands for higher shares of real income, the elites have not only caused the crisis but are now, in recovery, reinstating the dynamics that will lead to the next crisis.

The big changes in policy structures that have to be made to avoid another global crisis are not even remotely on the radar.

One of the defining characteristics of the neo-liberal period has been the relentless attack on the capacity of the workers to translate productivity growth into real wages growth.

I considered such distributional shifts in this early blog (2009) – The origins of the economic crisis.

The deregulation in the labour markets not only created increased job instability and persistently high unemployment but also led to large shifts in national income from wages to profits.

The G7 shifts shown in the graph above are minor compared to some nations. In Australia, for example, the wage share has gone from 60 to around 52 per cent.

A 2013 ILO Report written by Englebert Stockhammer – Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution – reported similar trends in other advanced OECD nations.

[Reference: Stockhammer, E. (2013) Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution, International Labour Office, Geneva]

The trends are summarised as such:

First, the wage share in national income has fallen significantly over the last 35 years in most nations. This is because real wages have lagged behind productivity growth. The redistributed national income has gone to profits.

Second, in the Anglo nations, “a sharp polarisation of personal income distribution has occurred” (Stockhammer, 2013: 2), with the top percentile and decile of the personal income distribution substantially increasing their total shares.

The munificence gained at the expense of lower-income workers manifested, in part, as the excessive executive pay deals that emerged in this period.

It has also channelled income into the unproductive casino we know as the financial markets – the gambling chips have come at the expense of real wages growth.

Up until the early 1980s, real wages and labour productivity typically moved together. As the attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified, a gap between the two opened and widened. The widening gap between real wages and productivity growth manifested as the rising profit share.

In 1975, the Australian wage share was around 62.5 per cent of factor income.It is now around 52 per cent.

The Australian government aided this redistribution in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce union power; National Competition Policy and such.

Similar policy approaches and shifts in labour market structure (increased casualisation etc) have occurred elsewhere.

We know what happened next. Imbued with the, now discredited, efficient markets hypothesis, promoted by University of Chicago economists, policy makers bowed to pressures from the financial sector and introduced widespread financial deregulation and reduced their oversight on the banking sector.

This not only led to a massive expansion of the financial sector, but also, set the stage for the transformation of banks from safe deposit havens to global speculators carrying increasing, and ultimately, unknown risks. The massive redistribution of national income to profits provided the banks and hedge funds with the gambling chips to fuel the rapid expansion of the ‘global financial casino’ expanded.

Increasingly, the Gordon Gekkos strutted the stage as celebrities and were cast as important wealth generators. Private returns were high and the lemming rush unstoppable.

But the reality was different. The vast majority of speculative transactions that occur every day in the financial markets are unproductive, in that they are unrelated to the real economy and advancing our welfare.

A substantial portion of the “wealth” generated was illusory and we subsequently discovered that the socialised losses were enormous as the huge, unregulated gambling casino collapsed under its own hubris, criminality and incompetence.

But the two arenas of deregulation created a new problem – one that Marxists would call a “realisation” problem. The capitalist dilemma was that real wages had to typically grow in line with productivity to ensure that the goods produced were sold.

So how does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in capacity to purchase (the real wage)? This was especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses, which squeezed private purchasing power in many nations during the 1990s and beyond.

The neo-liberal period found a new way. The ‘solution” was found in the rise of so-called ‘financial engineering’, which pushed ever increasing debt onto households and firms. The credit expansion not only sustained the workers’ purchasing power but also delivered an interest bonus to capital while real wages growth continued to be suppressed. Households, in particular, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. It seemed to good to be true and it was.

The increasing private sector indebtedness – both corporate and household – is another marked characteristic of the neo-liberal period.

Conclusion

The IMF solution for Japan is in fact one of the key changes that nations have to do bring in to restore some sense of stability into the world economy.

Governments around the world has to ensure that real wages growth, at least, keeps pace with productivity growth and that workers can fund their consumption expenditure from their earnings rather than relying on ever increasing levels of credit and indebtedness.

This will of course require a fundamental change in our approach to the interaction between society and economy.

It will require increased employment protection, larger public sector employment proportions, decreased casualisation, and legislative requirements imposed upon firms to pass on productivity gains.

It’s no small order, but it is one of a number of essential changes that we will have to do introduce as part of the abandonment of neoliberalism.

If the IMF is now making noises in this regard (if only discussing real wages growth) then some progress is being made.

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

I will write a separate blog about this presently, but today we finally published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text – today (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 US dollars)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 US dollars)

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics

Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism

Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts

Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model

Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement

Chapter 10: Money and Banking

Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation

Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy

Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations

Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations

Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available the week after next.

Note: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“So how does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in capacity to purchase (the real wage)?”

Financialisation is one solution.

The other is Feudalisation – replacing machines with people and subsiding them with government ‘tax credit’ payments. We see that here – hence the increase in hand car washes and coffee baristas, tasks which should be done by machines in any advanced nation.

The falling wage share is compounded by growing inequality amongst wages.

How has the distribution of the non wage share changed in the neo-liberal era?

Have we seen an increase in profits across the board?

Have we seen a particular raise in income for speculators in land and opaque financial

products?

Have firms who have been able to offshore labour to even cheaper international markets

increased their profits more than firms who provide services locally?

Where do I find reliable data on the distributional changes in the non wage share of GDP?

So how does all this fit with the fact that Japan has a slowly declining population?

Could it be that population reduction is not the disaster that the Growthists propagandize?

Kevin bill has posted many blogs and many graphs for a few countries in the past so might be worth having a look back at some.

In the USA there’s a horrifying graph the nytimes posted here: https://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2011/09/04/opinion/04reich-graphic.html

That graph clearly gives you an idea of where the money went to. Profits not wages!! The neo-liberal era of inequality.

Bill great post as always. I managed to get a number of comments published on that article citing your blog and the main points. Hopefully at least some readers and maybe the journalist can have their eyes opened. I encourage others to do the same wherever they see journalistic propaganda like this. I was lucky for a guardian reader to tell me about this blog. So I want to spread the word so we can have a human economic enlightenment hopefully before I leave this world.

On a side note and it doesn’t excuse horrible economics journalism like this but fairfax the author of the newspapers has just had more mass sackings in the last few days. Quality journalism is no longer profitable and I worry deeply about where people will get informed information in the future. Thankfully Australia has the public funded ABC for now but is slowly being destroyed by right wing governments. The good news is the guardian I’ve heard has enough money to fund itself for decades so at least we can hope they continue being a good source of journalism and hopefully even MMT one day!!

I had read a post on a different blog where it was argued that unless there were labor productivity increases the labor force participation rate in the U.S. would pretty much remain at its current reduced level. The reasoning seemed to go- increased productivity leads to increased demand for labor leads to increased wages leads to increased willingness to supply labor leads to increased LFPR. I have questions whether increased labor productivity always leads to increased labor demands. It seems to me that you need to make a lot of assumptions, some of them counter-intuitive to me, in order for that process to occur. I would rather just skip a few steps in the bloggers’ chain of thinking and go straight to increased wages. I think the IMF agrees with me here (which is very surprising to me).

And I like to argue that increased wages spurs firms to increase productivity anyway through more efficient use of their labor. And even if that is a bad argument, well you are left with higher wages and maybe a little more inflation worst case.

As Richard Wolff has pointed out, the rising gap between productivity and wages created a ‘bankers’ heaven’ in that the banks could now effectively ‘rent’ the currency to the vast part of the population whilst simultaneously inflating housing bubbles so that more ‘rentier’ activity could be created.

meanwhile in the good ‘ole UK, public assets are being flogged like never before the present Government is set to sell more than Thatcher did. Schools and the land they are on are being financilised as are substantial parts of the NHS.

How can we explain that the myths of ‘trickle down’ and ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’ are still so entrenched after 40 years of proven failure/graft/grift and chiselling?

An article in The New Yorker looks into how ‘magical thinking’ can persist after 40 years of evidence to the contrary:

“Indeed, Nyhan and the political scientist Jason Reifler carried out a study demonstrating that attempts to set the record straight can even reinforce misperceptions: self-described conservatives were shown evidence that the Bush tax cuts had lowered over-all revenues, but, Nyhan told me, “the information actually made them more likely to believe that the tax cuts had increased revenue.”

We’re dealing with something so deeply set in peoples’ psyche that I’m beginning to believe (sadly) that things will have to get a lot worse for any cranial light bulbs to flicker.

Wren Lewis has replied directly to you Bill on his blog

Derek Henry, yes, its starts off well, where he agrees with MMT about the obsession with debt…. but oh dear… there is all that stuff about intergenerational equity, ie passing on a burden to the next generation with the need for higher taxes tomorrow and crowding out… I can’t pretend to understand it perfectly, but I think it must be wrong. Deficit spending creates assets, like the NHS, schools, trained workers, roads, infrastructure. Is not that real wealth, an asset for the young? I really cannot see how government money can crowd out private investment, unless the banks would prefer people to borrow for profit rather than receive public services because it makes a profit for them.

Sandra Crawford, I agree with you. It seems to me that the costs of any public investment are borne by people in the economy at the time that investment is undertaken. These costs would be (at worst) in the form of reduced current consumption with possible inflation if the economy was already operating at full capacity at the time of the investment. These costs cannot somehow be switched to future generations through government debt. Future generations may have distributional problems with past debt issues, but that is an entirely different type of problem. And failure to invest now, almost certainly makes those future problems worse. And anyone who knows that this is wrong, please, please correct me and show me why I am wrong. Especially if you know what you are talking about. Or if your name is Bill 🙂

One thing I forgot to mention in regards to the affects of negative interest rates is that I read the opposite issue to Japan is happening in Europe from an article I read in project syndicate earlier yesterday. European banks unlike the Japanese rather than passing on the costs of negative interest rates to depositors and losing their deposits are instead trying to make up those losses through bank loans. This is actually decreasing the amount of lending and doing the exact opposite of what they’re trying to do. How can so many supposedly smart people be so wrong for so long and simply not see stop and question why? Japan to me is a great example of MMT being proof of economic reality. Maybe your new text book needs to be translated to Japanese ASAP Bill? Maybe we need a helicopter drop of a different kind: MMT educational material!

Jason H my question is profits to Who?

To all employers so all can raise wages without prices or to the parasitical elite?

Bloomberg has an article on “helicopter money” or OMF it seems. Maybe MMT will catch on eventually!

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-22/billions-from-heaven-helicopter-money-option-wins-fans