The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

The folly of negative interest rates on bank reserves

On Friday (January 29, 2016), the Bank of Japan issued a seven-page document – Introduction of “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with a Negative Interest Rate” – which left me confounded. Do they actually know what they are doing or not? For years, the liquidity management conducted by the operations desk at the Bank has been impeccable, in the sense that they have maintained near zero interest rates in the face of growing fiscal deficits. There was always some doubt when they were the early users of quantitative easing which many claimed was to provide the banks with more reserves so that they would increase their lending to the private domestic sector in order to stimulate growth, after many years of rather moderate real performance to say the least. Of course, banks are not reserve constrained in their lending so the the only way that this aspect of ‘non-conventional’ monetary policy would be stimulatory would be if investment and purchasers of consumer durable were motivated to borrow at the lower interest rates that the asset swap (bonds for reserves) generated. The evidence is that the stimulus impact has been low and that there are many other factors other than falling interest rates governing whether borrowers will approach their banks for loans. In their latest announcement, the logic appears to be that by reducing reserves they will induce banks to lend more. Go figure that one out!

The official announcement said the Bank:

1. Decided to introduce “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) with a Negative Interest Rate” in order to achieve the price stability target of 2 percent at the earliest possible time.”

2. “The Bank will apply a negative interest rate of minus 0.1 percent to current accounts that financial institutions hold at the Bank”.

3. The “outstanding balance of each financial institution’s current account at the Bank will be divided into three tiers, to each of which a positive interest rate, a zero interest rate, or a negative interest rate will be applied, respectively”. This is the so-called adoption of the “three-tier system”. It is designed to “prevent an excessive decrease in financial institutions’ earnings stemming from the implementation of negative interest rates”. More about which below.

3. “The Bank of Japan will conduct money market operations so that the monetary base will increase at an annual pace of about 80 trillion yen”. So more quantitative easing.

4. “The Bank will purchase Japanese government bonds (JGBs) so that their amount outstanding will increase at an annual pace of about 80 trillion yen.3 With a view to encouraging a decline in interest rates across the entire yield curve … The Bank will purchase exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and Japan real estate investment trusts (J-REITs)”. So they are planning to exchange a broad range of public and private assets for reserves. This is the qualitative aspect of the policy.

The decision to impose a negative interest-rate of minus 0.1 per cent was carried on a “5-4 majority”, a near thing in other words.

In its – Key Points of Today’s Policy Decisions – it said that it aimed to:

… lower the short end of the yield curve … [to] … exert further downward pressure on interest rates across the entire yield curve through a combination of a negative interest rate and large-scale purchases of JGBs.

It does this by effectively imposing a tax on banks for holding reserves above certain limits (as explained below). The interbank market will push rates down accordingly because banks will not be prepared to borrow from each other at higher rates. This, in turn, will push the longer maturity rates down.

Most of the flattening of the curve will come from the continued purchase of Japanese government bonds and other financial assets at various maturities along the yield curve.

It was doing this to “achieve the price stability target of 2 percent at the earliest possible time”, although it now said its would set the target as the first half of 2017 rather than much earlier as previously planned.

The ostensible reason given for the imposition of the negative interest rate tier is that the Bank is worried about volatility in global financial markets and desires “to maintain momentum toward achieving the price stability target of 2 per cent”. In other words, they think that by imposing a new public tax on the private sector it will promote exhilarating inflation.

In other words, they think the imposition of a new tax will be consistent with “additional monetary easing”, which means that we are now being told a tax rise is a stimulatory strategy.

I will come back to that soon.

I recognised that such measures as the negative interest-rate could impact badly on the “earnings of financial institutions”. But, in that context, the Bank claimed that “overcoming deflation as soon as possible and exiting from the low interest-rate environment lasting for two decades is essential for improving the business conditions for the financial industry”.

Also in the context of minimising damage to the financial institutions, the Bank introduced its new “Three Tier System” for pricing reserves.

The first tier, pays a positive interest rate of 0.1 per cent on what the Bank calls the Basic Balance. This covers all the existing reserves that are in the system from previous QQE exercises (around ¥220 trillion – that is, a fair pool).

The second tier, the so-called Macro Add-on Balance will receive a zero interest rate. This corresponds to the “amount outstanding of the required reserves held by financial institutions subject to the Reserve Requirement System” and the other reserves associated with loans to cover the earthquake-affected regions.

The third tier, the Policy-Rate Balance, which is the reserves not included in the previous two tiers, will attract a negative interest rate of -0.1 per cent.

What are the reserves in the third-tier? They are new reserves entering the system. Remember all the justifications for QQE were constructed around wanting to give the banks more reserves so they would increase their lending, notwithstanding the fact the bank lending in Japan or anywhere else is not reserve constrained.

Well, under the QQE policy, the Bank proposes to pump and additional ¥80 trillion per year into the banks’ reserve balances and then tax them 0.1 per cent into the bargain.

From the Bank’s perspective, the negative interest-rate decision is a cautious move relative to the ECB’s current practice of imposing a 0.3 per cent tax on all reserves (there are no tiers in their system).

Their logic is that if they followed the ECB practice immediately they could drive some banks broke or seriously impair their profitability.

Does that sound like it is a stimulatory (positive) move?

Why is QQE a furphy?

I have dealt with the question of reserves, inflation and lending before.

Please read my blogs – Quantitative easing 101 and – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Quantitative easing is not really capable of stimulating lending. Anyone who thinks otherwise doesn’t understand the banking operations that link monetary policy to bank reserves. Developing this understanding is a core differentiating feature of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

This workign paper from the Bank of International Settlements – Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal – is very useful in advancing this understanding.

It argued that mainstream economists have not really thought much about the unconventional monetary policies that have been used in this downturn by central banks.

In relation to these policies, the paper says that their:

… distinguishing feature is that the central bank actively uses its balance sheet to affect directly market prices and conditions beyond a short-term, typically overnight, interest rate. We thus refer to such policies as “balance sheet policies”, and distinguish them from “interest rate policy”.

In making this distinction, they show that these policies are intended to work by altering “the structure of private sector balance sheets” and targetting “specific” markets. The major points they make are as follows:

First they say that:

… rather paradoxically, some of these policies would have been regarded as “canonical” in academic work on the transmission mechanism of monetary policy done in the 1960s-1970s, given its emphasis on changes in the composition of private sector balance sheets.

That is, the recent history of macroeconomics has attempted to obliterate insights that were well understood during the “Keynesian” period.

They then say that a:

… key feature of balance sheet policies is that they can be entirely decoupled from the level of interest rates. Technically, all that is needed is for the central bank to have sufficient instruments at its disposal to neutralise the impact that these policies have on interest rates through any induced expansion of bank reserves (holdings of banks’ deposits with the central bank). Generally, central banks are in such a position or can gain the necessary means. This “decoupling principle” also implies that exiting from the current very low, or zero, interest rate policies can be done independently of balance sheet policies.

The “decoupling principle” is based on the way in which the central bank remunerates bank reserves relative to the policy rate, which is the rate it announces as its statement of monetary policy.

Consistent with MMT, there are two broad ways the central bank can manage bank reserves to maintain control over its target rate.

First, central banks can buy or sell government debt to “adjust the quantity of reserves to bring about the desired short-term interest rate” a practice that has been “well known to practitioners for a long time” (page 3).

MMT posits exactly the same explanation for public debt issuance – it is not to finance net government spending (outlays above tax revenue) given that the national government does not need to raise revenue in order to spend. Debt issuance is, in fact, a monetary operation to deal with the banks reserves that deficits add and allow central banks to maintain a target rate.

Second, “central banks may decide to remunerate excess reserve holdings at the policy rate” which “sets the opportunity cost of holding reserves for banks to zero”. The “central bank can then supply as much as it likes at that rate.” The important point is that the interest rate level set by the central bank is then “delinked from the amount of bank reserves in the system” just as in the first case when the central bank drains reserves by issuing public debt.

So the build-up of bank reserves has no implication for interest rates which are clearly set solely by the central bank.

Bringing those insights together the BIS paper said:

In particular, changes in reserves associated with unconventional monetary policies do not in and of themselves loosen significantly the constraint on bank lending or act as a catalyst for inflation …

The preceding discussion casts doubt on two oft-heard propositions concerning the implications of the specialness of bank reserves. First, an expansion of bank reserves endows banks with additional resources to extend loans, adding power to balance sheet policy. Second, there is something uniquely inflationary about bank reserves financing.

They correctly point out that those who think that an expansion of bank reserves provides banks with additional resources to extend loans assumes that “bank reserves are needed for banks to make loans”.

MMT outrightly rejects these propositions. Bank reserves are not required to make loans and there is no monetary multiplier mechanism at work as described in the text books.

The BIS authors concur and say that:

In fact, the level of reserves hardly figures in banks’ lending decisions. The amount of credit outstanding is determined by banks’ willingness to supply loans, based on perceived risk-return trade-offs, and by the demand for those loans. The aggregate availability of bank reserves does not constrain the expansion directly.

It is obvious why this is the case. Loans create deposits which can then be drawn upon by the borrower. No reserves are needed at that stage. Then, as the BIS paper says, “in order to avoid extreme volatility in the interest rate, central banks supply reserves as demanded by the system.”

The loan desk of commercial banks have no interaction with the reserve operations of the monetary system as part of their daily tasks. They just take applications from credit worthy customers who seek loans and assess them accordingly and then approve or reject the loans. In approving a loan they instantly create a deposit (a zero net financial asset transaction).

The only thing (other than its capital) that constrains the bank loan desks from expanding credit is a lack of credit-worthy applicants, which can originate from the supply side if banks adopt pessimistic assessments or the demand side if credit-worthy customers are loathe to seek loans.

The BIS authors then demonstrate that:

A striking recent illustration of the tenuous link between excess reserves and bank lending is the experience during the Bank of Japan’s “quantitative easing” policy in 2001-2006. Despite significant expansions in excess reserve balances, and the associated increase in base money, during the zero-interest rate policy, lending in the Japanese banking system did not increase robustly

And that really is the issue?

Japanese banks are not expanding credit not as a result of their unwillingness to make loans or a lack of reserves. The reason for the slow credit is that businesses have sufficient capital stock to satisfy the demands of a very weak consumption sector and do not need to borrow.

Until they expect stronger consumption growth or better export potential, the firms will keep the investment ratio rather flat (at around 13 per cent of GDP).

Negative interest rates will not alter that.

It will only change when firms perceive better investment prospects.

Some might think that the banks will pass the ‘tax’ (negative interest rates) on to depositors, which might stimulate them to run down their deposit balances and spend or park then into higher-yielding investments.

Once again, this ignores sentiment. Households and firms hang on to cash as a liquidity measure to transcend time while they are uncertain of the future.

If they were confident they would already be spending more. It is also highly unlikely that reducing deposit rates will alter sentiment. If sentiment was to change, it is likely that it would lean towards a more pessimistic outlook, given that this measure looks like the central bank is getting desperate and no longer really understands what is going on.

How is Japan faring?

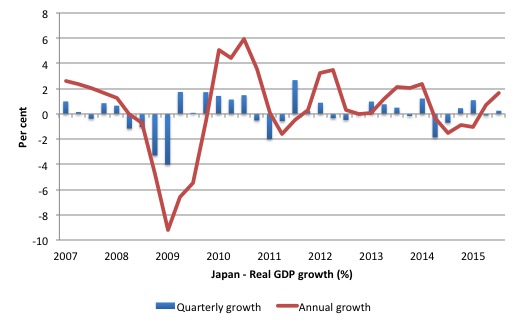

The following graph shows the growth of real GDP from the March-quarter 2007 to the September-quarter 2015. The annual growth (year-on-year) is in blue bars while the red line is the quarterly growth rate.

On an annual basis, Japan came out of recession in the June-quarter and this growth was consolidated in the September-quarter.

The latest annual growth rate of 1.7 per cent built on the strong growth earlier in 2015 and a 0.3 per cent growth rate for the September-quarter itself.

The sudden negative spike in the June-quarter 2014 result was the direct outcome of neo-liberal incompetence (the sales tax hike) and is no longer affecting the annualised growth rate calculation.

But the quarterly result for the September-quarter 2015 is a good sign for Japan, given it was driven by stronger growth across all the expenditure categories.

The Abe government raised the sales tax from 5 per cent to 8 per cent in April 2014 as part of a ridiculous plan to reduce the fiscal deficit.

While domestic demand slumped for several quarters following the sales tax hike it is grew at 1.42 per cent on an annual basis in the September-quarter.

Please read my blog – Japan returns to 1997 – idiocy rules! – for more discussion on the damaging impacts of sales tax hikes.

The sales tax hike was a replay of the events that occurred in 1997 when the ideologues came out in force and pressured the national government to cut into the fiscal deficit.

The government raised the sales tax then with disastrous consequences. The lessons clearly have not been learned.

I discussed the 1997 debacle in detail in this blog – Japan thinks it is Greece but cannot remember 1997

The latest – Consumer Confidence Survey – published by the Cabinet Office (January 12, 2016) showed that:

1. The index was up 0.1 percentage points in December 2015 from November 2015 and has been recovering over the last few months prior after hitting negative territory when the sales tax hike was implemented.

2. Two of the four components of the index rose in December (overall livelihood, 0.2 points; income growth, 0.7 points; employment, -0.4 points) and willingness to buy durable goods, unchanged).

So household consumption expenditure is still fragile as the impacts of the sales tax hike persist.

Private consumption finally resumed positive annual growth in the September-quarter 2015

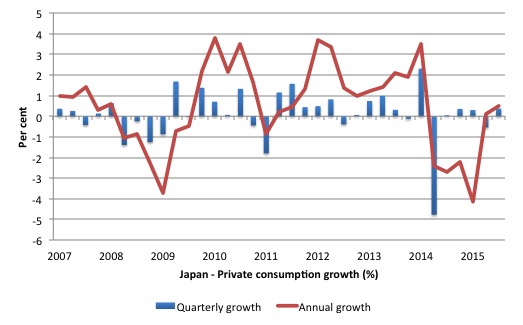

The following graph shows growth in private consumption spending since the March-quarter 2007. The blue bars are the annual (year-on-year) outcome, while the red line is the quarterly result.

The sales tax hike had the predictable negative effect with a sudden dive in consumption overall in the June-quarter 2014 (-4.8 per cent) followed by four quarters where growth averaged zero percent.

The combination of the sales tax hike, declining real wages, and the export decline caused the quarterly growth of private consumption to decline again in the June -quarter 2015 (-0.5 percent), which all but wiped out the gains made since the March-quarter 2014.

The recovery in the September quarter (0.4 percent quarterly growth) is driven by a slight increase in confidence and continued support for growth from the public sector (fiscal policy).

The poor consumption performance also impacted on private sector investment. However, Private non-residential investment also resumed growth in the September-quarter 2015 (0.6 per cent quarterly growth and 2.3 per cent annual growth).

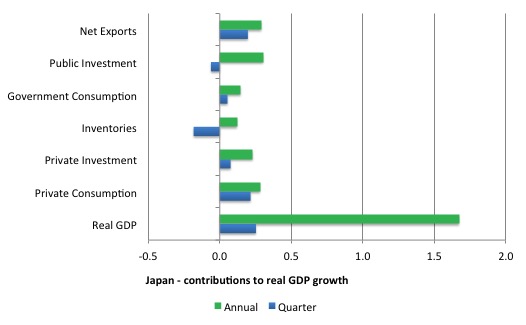

The next graph shows the contributions (in percentage points) to real GDP growth of the major expenditure categories in Japan over the last quarter and over the last 12 months (to the September-quarter 2015).

Growth coming from all the major expenditure environments in the September-quarter 2015 with the public sector spending on consumption and public infrastructure complementing a broad non-government spending recovery.

Net exports contributed to growth and both exports and imports rose (a good sign – the latter indicating domestic income has risen).

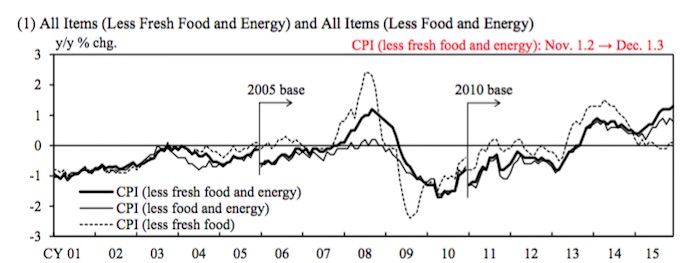

The Bank of Japan publishes various – Measures of underlying inflation or ‘Core’ inflation to guide it in its monetary policy decisions.

The latest Bank of Japan publication Measures of Underlying Inflation was published on January 29, 2016.

The following graph taken from the Bank’s publication shows the various measures of call CPI inflation since 2001.

We see that the Bank’s preferred measure of underlying inflation – CPI (less fresh food and energy) – grew by 1.3 per cent in December 2015. This is in fact, the fastest acceleration in the index since the March 1994 when Japan was struggling to get out of the property collapse.

This measure has been consistently positive since August 2013.

Its broader measure, which excludes only fresh food (that is, ignores the declining oil price effects), however, was barely positive.

Clearly, the Bank’s claim that it wants to engineer a 2 per cent inflation rate is being thwarted by this data. It announced last Friday among its tranche of policy statements that it was now pushing out

But does that matter? The period of deflation appears to be over in Japan at present. So low inflation at least is to be expected in the coming year or so.

One argument supporting the negative interest rate move is that with low inflation, firms have no incentive to accede to higher wage demands.

Spring is approaching for Japan and that means the ‘spring wages offensive’ (Shuntō) is also approaching. The government has indicated it is keen to drive inflation higher to encourage higher wages growth, which in some why is meant to stimulate economic growth.

The reality is that this years enterprise bargains between unions and firms will see further wage suppression given the weakness in the economy. Further, even if inflation and nominal wages growth was to rise, the real wage is unlikely to rise far enough to have a significant effect on the real purchasing power of workers.

Conclusion

QE built bank reserves, allegedly to encourage the banks to lend more. Now negative interest rates are being used in the hope of reducing bank reserves, in the hope that banks will lend more.

If you think we are entering the land of absurdity, you wouldn’t be far wrong.

The National Accounts data shows what generates growth. Strong public sector contributions providing a basis for renewed optimism among households and firms who then also spend more.

Basic macroeconomics. The Bank of Japan should just sit tight and let the Ministry of Finance do the work.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

There’s more to this than meets the eye in my opinion. To me this looks all political.

I think the US has leaned on Japan here because of what China is doing when they founded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Recognising the challenge, the US intensively lobbied allied states in Asia and Europe to stay out of the AIIB, arguing that it would not meet IMF and World Bank standards of transparency, environmental and social responsibility, and democratic governance. With the exception of Japan, the US proved unable to sway its closest partners.

Plus it competes with the the Japanese-led Asian Development Bank.

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers wrote that October 2014 (when the AIIB was formed) “may be remembered as the moment the United States lost its role as the underwriter of the global economic system.

As Obama put it in his 2015 State of the Union address: “China wants to write the rules for the world’s fastest-growing region. Why would we let that happen? We should write those rules.”

If negative interest rates don’t benefit Japan then who do they benefit ? Or who also do they hurt?

“Debt issuance is, in fact, a monetary operation to deal with the banks reserves that deficits add and allow central banks to maintain a target rate.”

Just on the overnight or all the way up the yield curve?

Is there any reason why Australian joined the Asian Infrastructure Fund ?????

Bill,

Any rationale for 2% inflation target or another wet finger in the air job as EU’ s 3% for SGP etc?

Housing inflation in most major cities is some 2 or 3 times the inflation target -is this an unintended result of QE/QQE?

Frances Coppola has a suggestion, which looks plausible to my untrained eye, that this is just a ruse by the Japanese to weaken the yen and boost exports while pretending to their trade partners that they are doing something more politically palatable.

Will we ever see QE for the people in Australia ? I thought it was against the Lisbon treaty … but Iceland did it so why not ?

I’m struck most by the contradictory policies of taxing reserves while adding reserves via QE. A simultaneous reserve drain/add will stimulate lending? That doesn’t conform to any school of thought with which I’m familiar.

“QE built bank reserves, allegedly to encourage the banks to lend more. Now negative interest rates are being used in the hope of reducing bank reserves, in the hope that banks will lend more.

If you think we are entering the land of absurdity, you wouldn’t be far wrong.” Bill Mitchell

I was mystified too since the commercial banks don’t lend to the private sector since the private sector does not have reserve accounts at the central bank to make this possible*. Instead, the commercial banks create additional liabilities to their reserves when they “lend” to the private sector.

But a negative interest rate on reserves would make reserves a hot potato that banks wish to get rid of, it seems. But how? One way is for a small bank to increase “lending” confident that its new liabilities will end up with competing banks which will then drain the small bank’s reserves via inter-bank check clearing. This strategy is less likely to work with a large bank since checks are then more likely to be from one of the bank’s customers to another with no inter-bank reserve transfer.

Another way is for the commercial banks to lobby for a tax increase by the monetary sovereign since such taxes destroy reserves (account balances of the monetary sovereign at the central bank are not reserves since the monetary sovereign is not a commercial bank nor does it participate in inter-bank lending).

More pondering needed though …

*Ignoring the possibility that a commercial bank might buy physical cash with its reserves and lend that to a private sector borrower.

aka, we can see Reserves can’t leave the banking system. Hence, it is an inescapable tax.

Bill, you may well find this information helpful:

https://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2016/k160129b.pdf

Bob,

For the commercial banks as a whole, it’s an inescapable* tax but an individual bank might reduce its share of the tax by new liability/deposit creation which should shed some reserves via inter-bank check clearing. But that’s the purported purpose – to spur new “lending” by the commercial banks, not to benefit the commercial banks themselves, who would be competing to shed the most reserves without making bad loans while the overall reserves kept increasing.

*well almost since a commercial bank could buy vault cash with its reserves, I suppose.

The crisis of economic mismanagement is like the crisis of environmental management. Only a salutary disaster will convince people to change course. What do I mean by a “salutary disaster”? Essentially, I mean a disaster so big it teaches everyone a lesson they can’t ignore. The Great Depression was such a disaster. The people and their governments could no longer ignore the fact the system wasn’t working. They had to change or the people faced starvation and the governing elites faced revolution and being hung from lampposts. It is the same with the environmental crisis. Nothing serious will be done about global warming (for example) until a chunk of Greenland ice sloughs off rapidly enough to raise the sea level half a meter in a decade or bush fires raze California end to end in a couple of seasons. Only then will something be done.

So long as a salutary disaster does not happen in the economy or the environment, the elites can keep telling lies and the people can keep being credulous. The value of analytical and prognostic thinkers like Bill Mitchell will only come to the fore when the salutary disaster(s) hit. Before such times they are ignored. When those times arrive, their bodies of work will be recognised as crucially important and then applied. One can only hope the time will not be too late.

People are rarely convinced by argument. They are largely convinced only by force. As it would be immoral, contradictory and counter-productive to apply human force to force people to be good or sensible, then one has to wait for natural forces to apply the force. One can attempt to teach and instruct. Such measures can work well on the young, on a new generation. However, elite mature people entrenched in positions of power and privilege or ordinary mature people entrenched in general prejudice and complacency rarely respond to logic or sense when the naturally or systemically mandated new paradigm is outside their experience. They just can’t get it. But overwhelming natural force or human system systemic collapse works. Then they get it.

I wish I could have a more sanguine view of the ability of humans to show foresight and wisdom but over sixty years of experience on this planet suggest to me that the contrary is the case. It seems that to be impervious to groupthink one must always have been an outsider as well as being sufficiently intelligent and educated to deconstruct pervading lies and myths. Only outsiders can fully see and think without the blinkers and presuppositions of in-group groupthink.

Professor forgive the question you may have answered this before elsewhere. I have never understood why the central banks continue with this policy when it does not work.

We seem to be suffering from a soft depression globally as the credit boom has died over the years. In the current monetary system, if I use the bank of England description money is “Loaned into Existence” the credit creation process then multiplies the money supply throughout the economy generating growth????

Now the banking systems appear to be totally “loaned up” and this system no longer works.

Why can’t Central banks just issue “debt free” money to the government to be spent on transfer payments or other programs to create the monetary expansion the banks in their solvent former life used to provide.

Sounds crazy but I have been watching this disaster in slow motion since before 2008 and I see no difference between the banks issuing credit and creating money or this role passing to the government .

The public as usually will be distracted by wars and football so will never know the difference

Derek Henry, as for who might hurt, Bloomberg suggests that countries may be engaging in a currency war of competitive devaluations, acknowledging also that banks may be less willing to lend under present conditions. They don’t provide a great deal of evidence for this.

Sadly, I misspelled the Swedish Royal bank’s name as if it were Dutch. It, of course, should be Riksbank.

“since the private sector does not have reserve accounts at the central bank to make this possible*.” aka

A gross violation of equal protection under the law, btw.

Stephen,

You seem to believe the fractional reserve theory of banking, according to which banks can collectively create money (via the multiplier) but individual banks can’t.

However, the credit creation theory of banking is different: it holds that each individual bank can create money “out of nothing” by the simple act of extending credit.

When banks make a loan they create a deposit and a loan. No prior cash needed. Banks have access to reserves when needed via the central bank.

Firstly a bank creates a loan. So the loan is to person A, and firstly the deposit is to person A as well. At that point the bank is still fine and still fully funded.

What happens then though is that person A wants to pay person B.

If person B is at the same bank, then there is NO problem. The deposit is switched to person B and the bank is still fully funded.

The fun starts when person B is at another bank.

What has to happen that is that bank 2 has to take over the deposit in bank 1 from person A. That increases the assets of bank 2 which then creates a new deposit for person B.

That’s how payment works. Somebody has to take the place of the original depositor in the source bank before you can create anything in the target bank.

Of course at that point bank 2 is taking a risk on bank 1 and will expect to be paid by bank 1 an interest rate to compensate for that risk.

And it also means that if bank 2 isn’t prepared to take a risk on bank 1, that nobody in bank 1 can pay anybody in bank 2.

It’s this latter point that caused the creation of central banks – to make sure that the payment system clears. The theory being that all the banks trust the central bank ‘in the last resort’ and therefore the central bank can ensure payments always clear.

So the cost of funding is really the payments bank make so they can be part of a payment clearing system.

I suggest you read this Bill Mitchell Blog – Money multiplier and other myths, that explains why the money multiplier is incorrect:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=1623

This is another nail in the coffin of the money multiplier myth.

A central bank attempting to decrease the amount of reserves to encourage lending.

Behind the smoke and mirrors I think the aim is clear .Another attempt to increase

lending by driving down the real interest rates borrowers actually get.Yes there may

be another signal intended to devalue the currency to boost exports.

It is unlikely to work because of Japan’s workers chronic income stagnation despite

low unemployment levels.Households are unlikely to take on big purchases and

firms unlikely to expand production with chronic lack of customers money tokens.

This problem is not confined to Japan .Financial speculation ,bubbles growing and bursting,

here in the UK annual house price rises are close to 10 % nationally all signs of investors

seeking return but not finding it in providing real goods and services .

Mass consumerism and stagnant incomes are not a winning combination if only

there was a way to increase household income without increasing firms costs.