With an national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Japan – another week of humiliation for mainstream macroeconomics

In September 2010, The Project Syndicate, which markets itself as providing the “Smartest Op-Ed Articles from the World’s Thought Leaders” gave space to Martin Feldstein – Japan’s Savings Crisis. Like a cracked record, Feldstein rehearsed his usual idiotic claims that interest rates in Japan would rise because “of the continuing decline in Japan’s household saving rate” and that “the higher interest rate would eventually raise the government’s interest bill by about 4% of GDP. And that would push a 7%-of-GDP fiscal deficit to 11%”. Then, so the story goes, “This vicious spiral of rising deficits and debt would be likely to push interest rates even higher, causing the spiral to accelerate”. At which point, Japan sinks slowly into the sea never to be seen again. It turns out that the real world is a little different to what students read about in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks. At the risk of understatement I should have said very (completely) different. Better rephrase that to say – what appears in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks bears little or no relation to the reality we all live in. Anyway, events over the last week in Japan have once again meant that this has been just another week of humiliation for mainstream macroeconomics – one of many.

One should note at the outset that the predictions of Harvard Professor Martin Feldstein should always be disregarded. Please read my blog – Martin Feldstein should be ignored – for more discussion on this point.

With the Eurozone crisis on-going, commentators have regularly suggested that any day now, Japan is likely to follow Greece down the path to bankruptcy.

On April 11, 2010, a Agence France journalist wrote that the – Risk of Japan going bankrupt is real, say analysts.

A ‘chief economist’ at some Japanese research institute was quoted as saying:

Japan “can’t finance” its record trillion-dollar budget passed in March for the coming year as it tries to stimulate its fragile economy

Then one of those dubious rating agencies “warned that it might cut its rating on Japanese government bonds, which could raise Japan’s borrowing costs amid the faltering efforts of Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama’s government to curb debt”.

To which we should all respond “so what, big deal”.

The ‘chief economist’ intoned again that:

It’s hard to predict when the bond market might collapse, but it would happen when the market judges that Japan’s ability to finance its debt is not sustainable anymore … And when that happens, the yen will plummet and a capital flight from Japan’s government bonds to foreign bonds will occur.

And, remember this quote:

Since the mid-1990s the government debt has followed an explosive path, and policymakers and economists have come to think that there is no more room for fiscal expansion, which had been the major policy tool to cope with the protracted slump throughout the 1990s …

The quote came from a paper – Fiscal Consequences of Inflationary Policies – written by Japanese economist Keiichiro Kobayashi, who is a Senior Fellow of Research Institute of Economy, Trade & Industry, (RIETI) and holds various other appointments.

He is a fairly prominent author and commentator in Japan. Here he is, presumably illustrating graphically how much he knows about macroeconomics, which is not much judging by the distance being demonstrated.

In the paper, Dr Kobayashi outlined a model, which augmented a model that Paul Krugman used to make embarassingly wrong statements about the Japanese economy in the late 1990s. Please see this blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more detail on that.

Dr Kobayashi concluded that:

The policy implication of the above argument is that the Japanese government should undertake a more aggressive fiscal (and monetary) expansion today in order to escape from the liquidity trap. But huge fiscal deficits and the government debt, which is building up at an explosive rate, are also extremely serious problems in the Japanese economy.

When was this paper written? Answer: 2002.

Not to be put of by reality, Dr Kobayashi gave an interview on April 9, 2012 – Build up foreign currency assets to ease pain of bond market crash – to the Asahi Shimbun, which is one of the leading daily newspapers in Japan and offers an on-line news service on Asian and Japanese issues in English.

He told the journalist that:

Japan is in a situation where it … must keep piling on new debt to pay off old debt. In other words, its debt is snowballing. Actually, however, prices of Japanese government bonds, or the government’s IOUs, will tumble before a fiscal collapse or the government’s default on its debt.

To clarify, if Japanese government bond prices are falling then yields are going to be rising. So his prediction was that we should expect, any time soon, the Japanese government bond yields would be shooting up as their price bids were tumbling down.

He even said that “Government bond prices would crash” as there would be “more sellers than buyers” – which, of course, is not a concept applicable to the primary issue market where bond auctions are conducted. There the appropriate measure of demand is the Bid-to-Cover ratio.

The bid-to-cover ratio is just the the volume of the bids received to the total volumes desired in whatever currency the auction is being conducted.

So if the Japanese government wanted to offer 2,400 billion yen worth of 10-year JGBs and there were bids worth 6,997.3 billion yen in the auction, then the bid-to-cover ratio would be 2.916.

That is, nearly three times as many yen bids for the debt-issuance offered.

Which is exactly what happened on Tuesday, March 1, 2016, when the Japanese Ministry of Finance floated the auction tender number 342 for 10-year bonds, to be issued on March 22, 2016 and maturing on March 20, 2026 (Source).

The “Yield at the Lowest Accepted Price” was -0.015 per cent. In English, minus zero point zero one five per cent. And the “Yield at the Average Price” was -0.024 per cent.

This was the first time ever that the Ministry of Finance issued 10-year JGBs at negative yields.

What does that mean?

Which means that bond purchasers are paying the Japanese government to buy 10-year JGBs, which will mature on March 20, 2026.

Another way of saying this is that if a person holds the bond until its maturity, they would receive less than they had paid.

The MOF ended up issuing 2,187.9 billion yen of these 10-year bonds.

And there are around three times the demand for this issue (as indicated by the bid-to-cover ratio).

Many claim the bid-to-cover ratio is an important indicator of an impending crash in the capacity of a bond-issuing governemnt to continuing ‘funding itself’.

First, the bid-to-cover ratio doesn’t matter much at all as a diagnostic because the Japanese Government is not revenue-constrained so it could just abandon the auction system whenever it wanted to if the ratio fell to 0.00001.

Hmmm.

Second, the bid-to-cover ratio is highly interpretative as to what it signals. It certainly signals strength of demand but how strong becomes an emotional/ideological/political matter. Even if you believed that the government was financing its net spending by borrowing, then a bid-to-cover ratio of one would be fine – enough lenders to cover the issue. Some commentators think that 2 is a magic line below which disaster is imminent. There is no basis at all for that.

There is also no basis in the common claim that a ratio above 3 is successful and by implication a ratio below 3 is unsuccessful. After all, anything above 1 tells you that some investors do not get their desired portfolio. That sounds like a failure to me.

Third, the whole concept is skewed away from a sensible depiction of how the system works. As I have noted in the past, there is no shortage of funds created in the financial markets as a result of net government spending. The idea that this spending sets up a funding exigency that diverts scarce investment funds from other purposes is completely false.

Net government spending finances the desire of the non-government to save and thus creates the funds that make that saving possible. Whether that saving is expressed in tenders for government bonds or other financial assets including cash deposits at banks is another matter and not germane to the point.

The funds that the non-government sector uses to buy the bonds, ultimately come from the past deficits run by government in the first place!

Of course, I could have started this little historical sojourn in the mid-1990s rather than during the GFC. There were many similar predictions of doom and gloom for Japan and their capacity of the Japanese government to continue to run relatively substantial fiscal deficits.

For the last quarter of a century, or thereabouts, we have been on standby for the Japanese bond market to collapse and the country to declare bankruptcy.

Those who follow the markets have been keeping their eyes on the Bid-to-Cover ratios for each monthly bond tender – watching for the moment that private ‘investors’ lose faith in the JGBs and refuse to bid. Nothing like that has happened. The Bid-to-Cover ratio in the primary issue on all maturities fluctuate around but there are always bids that do not get satisfied.

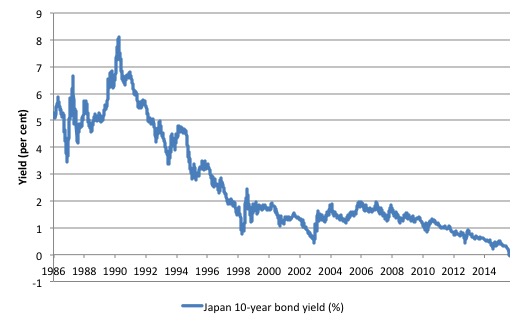

You might like to refresh your memory of the history of the Japanese 10-year bond yield since it was first issued on July 5, 1986 to February 29, 2016. The daily data (all 10,724 observations) is available from the – Japanese Ministry of Finance).

In May 2013, the commentators went ballistic again because there a little upturn in the yields sent them apoplectic and we heard a volley of predictions were that the end-game for the Japanese government was finally manifesting.

The story that headlined in all the financial news outlets was that the bond markets were finally calling in the piper and unless the Japanese government instituted a major fiscal austerity campaign all hell would break loose with respect to yields. At the time I commented – noting this was all nonsense.

Please read my blog – The last eruption of Mount Fuji was 305 years ago – for more discussion on this point.

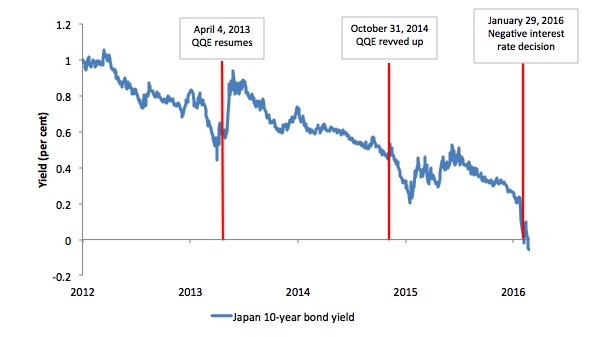

Just before that (April 4, 2013), the Bank of Japan had announced they were resuming their program of – Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) – which involves the Bank using its endless capacity to buy things that are for sale in yen entering the secondary JGB market and more recently corporate debt markets and spending up big.

Big means around “60-70 trillion yen” a year (see Statement Introduction of the “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing”)

On October 31, 2014, the Bank of Japan announced it was expanding the QQE program.

It would now “conduct money market operations so that the monetary base will increase at an annual pace of about 80 trillion yen (an addition of about 10-20 trillion yen compared with the past).”

Then on January 29, 2016, the Bank issued the statement – Introduction of “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with a Negative Interest Rate” – which augmented the QQE program – continuation of the annual purchases of JGB of 80 trillion yen and the application of “a negative interest rate of minus 0.1 percent to current accounts that financial institutions hold at the Bank”.

I considered that last decision in this blog – The folly of negative interest rates on bank reserves.

Here is what has happened to the 10-year JGB yields since 2010 to February 29, 2016, with the announcements demarcated by the red vertical lines.

The explosion in yields have not panned out folks, Japan remains above sea-level!

The fact that the Bank of Japan has been buying up government debt at its leisure clearly allows us to conclude that it is a monopoly supplier of bank reserves denominated in yen.

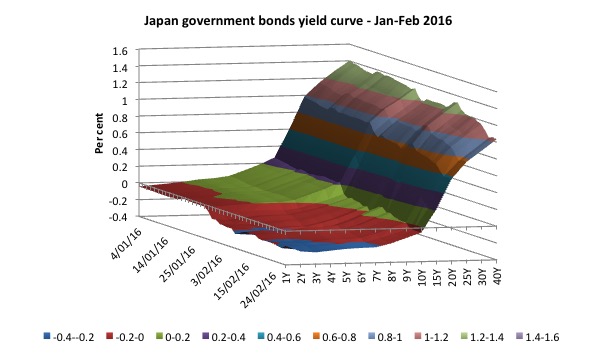

Now before we determine how much the Japanese government has been buying its own debt consider the next extraordinary graph, which doubles as a nice piece of art.

For readers unfamiliar with reading surface charts of yield curves, the vertical axis shows the yields (depicted in the coloured legend at the bottom of the graph). The horizontal axis shows the maturity of the debt instrument issued from 1-year to 40-year JGBs.

The depth axis shows the date – which in this case is from January 4, 2016 to February 29, 2016.

The shifting coloured patterns and the descending values across all maturities indicates that the Japanese government bond yield curve has flattened considerably since the beginning of 2016 and negative yields have spread out to the 10-year bond issues and even more negative yields have spread from the 1-year bonds out as far as 7-year bonds.

The flattening and the negative yields is a quite extraordinary occurrence. It has never been as flat as this across the maturities span.

At the last auction for 40-year bonds (February 23, 2016), the Yield at the Lowest Accepted Price was 1.130 per cent – that is, people are prepared to ‘save’ for the next forty years (until March 20, 2055) at 1.130 per cent!

The February 16, 2016 auction for 20-year JGBS, the yield accepted was 0.792 per cent (these bonds will mature on December 20, 2035).

While the bond market dealers are clearly still queuing up to get as much Japanese government debt as they can (as evidenced by the Bid-to-Cover ratios).

But, further to that, the Bank of Japan is clearly demonstrating its capacity to control yields at whatever level they choose.

A visit to the WWW page – Japanese Government Bonds held by the Bank of Japan (last updated March 2, 2016) – is highly informative and I recommend it as a weekly task for your Internet surfing (-:

Last year, the Ministry of Finance held 12 monthly auctions with 2.5 trillion yen per auction.

In line with the decisions at the Monetary Policy Meeting on April 4, 2013 (Introduction of the “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing”), the Bank has been buying JGBs worth between 10 and 12 trillion yen per month in the secondary bond market – that is, after they are issued to the authorised dealers who participate in the auction process and begin to be traded.

The secondary JGBs market is very thin at present given the demand from the Bank of Japan and the fact that sellers in that market are declining.

Why? Because as the auction yields have gone negative, current bond holders who purchased the debt instrument at positive yields, will worry about having funds (from sales) which are only going to attract negative returns (losses). The smart strategy in that case is to maintain long positions.

In December 2010, the Bank of Japan held around 7.4 per cent of all the outstanding JGBs (across most maturities). By December 2015, that ratio has risen to 32.4 per cent and will rise further as the QQE program continues.

Since the April 2013 announcement, the monetary base has risen from 968,904 trillion yen to 3,659,039 trillion yen (as at February 2016).

The monetary operations really just mean that the Japanese government is spending by using credits created by the Bank of Japan, whatever else the accounting structures might lead one to believe.

The conservatives who have been totally blindsided by these developments have started to introduce a new spin to regain credibility.

They now claim that there are no incentives for the government to engage in ‘necessary’ fiscal austerity and as a result Japan will go bankrupt more quickly than they predicted – forgetting to mention they have been predicting bankruptcy for 20 or more years.

Let me summarise the reality:

1. The Japanese government can never run out of money (yen). It is impossible. Therefore it can never become bankrupted.

2. The Bank of Japan can maintain yields on JGBs at whatever level it chooses, at whatever maturity range it targets, and for as long as it likes. The bond market investors are incidental to that capacity and are supplicants rather than drivers.

3. The size of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet (monetary base) has no relationship with the inflation rate.

4. If the Bid-to-Cover ratio fell to zero – that is, private bond dealers offered no bids for an auction – then the government could simply instruct the Bank of Japan to buy the issue. A simpler accounting device would be to stop issuing JGBs altogether and j

just instruct the Bank to credit relevant bank accounts to facilitate the spending desires of the Ministry of Finance.

5. If private investors choose to buy other assets once the risk in international markets subsides then the Japanese government (the consolidated central bank and treasury) could just buy more of its own debt – to near infinity. End of discussion.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Further, to refresh your understanding – the requirements for a sovereign currency-issuer with no default-risk are:

1. Issues its own currency.

2. Floats it on international markets – no pegs, etc.

3. Doesn’t borrow in any other currency.

4. Doesn’t offer any guarantees of convertibility to another currency.

That is why the Japanese government has zero (not low) default risk on any liabilities that it issues.

Conclusion

Another week of humiliation for the mainstream economics profession!

Weekend Quiz

The Weekend Quiz (formerly known as the Saturday Quiz) will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks Bill for the nice analysis.

Surely Japan should do something radical and just cut the sales tax rate to 0% or mail out cheques to all citizens for a certain amount like Australia did during the GFC to kickstart demand within the limits of inflation modelling. Then finally MMT and would be proven and the world could finally progress with trying to solve real issues like renewable energy technology and infrastructure.

I wonder if anyone in Japan even knows of MMT’s existence to start at least spreading the word?

Dear Bill,

what happened to the articles about the KfW in Germany you wanted to write?

This stuff is so easy to see. So how to explain the “World’s Thought Leaders” and their complete blindness?

Benedict,

Unlearning is much more difficult than learning, particularly when your career is based on what needs throwing out the window.

Dear Bill

I agree that the default risk of Japan’s bonds is zero, but that doesn’t explain why bondholders content themselves with such extremely low yields. The explanation must be that a lot of business have no alternative assets to buy. It can’t be the households since their savings rate is low.

Interest rates in Japan are very low and the government runs deficits, so why isn’t the Japanese economy growing faster? Maybe it is growing as fast as it can. If productivity growth is sluggish and the labor force is shrinking for demographic reasons, then the economy can’t grow fast unless there still are a lot of idle resources, which isn’t the case in Japan. Despite all the lamentations about Japan’s stagnation, it has a low unemployment rate and it has been growing. Maybe there really isn’t a Japanese economic crisis. With a shrinking labor force, there is of course not so much need for investment. In any case, analyzing Japan’s economy without taking demographic factors into account, is highly misleading.

Regards. James

They won’t stop repeating the beliefs. Over and over again using whatever medium is available to them to project their ill deserved authority.

Facts have no effect on propaganda.

Jason H: “Surely Japan should do something radical and just cut the sales tax rate to 0% or mail out cheques to all citizens for a certain amount […] to kickstart demand”.

An itchy question for me for the past while has been: “What does a zero-growth economy look like?” Post Club-of-Rome it seems as though we need such things. If the Japanese economy were a prototype of a ZGE, then maybe it ought not to be kickstarting demand at all. Since I’m not an economist, I can ask, but I have no clue how to answer.

I also am interested in the question from James Schipper. Maybe it is possible that Japan has already achieved that state where all its people have all their basic material needs met. If everyone has adequate housing, and medical care, and education, and food, and is reasonably happy about it (as in not being stuck in a prison or work camp)- then maybe the situation shouldn’t be described as an economic crisis. Actually, it sounds more like a Star Trek world situation where people can devote their time to improving themselves and the rest of humanity, and random aliens of course (hey, I was a big fan). So maybe Martin Feldstein shouldn’t be worrying so much. It doesn’t seem that his writings are doing much to improve the human condition. Maybe he can focus on getting other countries nearer the Japanese model instead.

Dear Bill

Great blog post and thanks for the link to BOJ for the read!

The literature from the deficit alarmists reads like the anti-vaccination movement. It just boggles the mind as to how they can set up a domino like chain of misconceptions/fallacies to reach their conclusions.

I think of the central bank fiscal function in the way i think of a software compiler.

I never doubt the ability of the computer to make a call to address space/make a pointer, i can make infinite calls for address space to implement an algorithm/solve a problem. Ultimately what constrains me is the physical memory environment of the computer itself. In this way its like a central bank it neither has/does not have funds it is an instantiation of address space/currency.

James and Jerry with neo-liberal economics and an overworking culture in Japan that actually has a word for dying by overwork “Karoshi” and a high suicide rate Japan is far from the perfect model. It’s closer than many western countries to it possibly but isn’t perfect. Norway may be a better model but I’ve lived there and they have their own issues particularly with liberal drug laws that enslave too many people to heroin with people passed out in parks in the centre of Oslo. It was shocking to be honest and minor crimes like theft was high too in Oslo. Neo-liberal economics has taken over everywhere. Why for example does Norway depend on its sovereign wealth fund from selling oil to build a hospital for example? If resources are available and it’s needed then build it using the local currency. You don’t need foreign currency to do that.

Japan has too much poverty and social issues like hiring homeless to clean up nuclear waste: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-fukushima-workers-idUSBRE9BT00520131230

If Japan could kick neo-liberal economics then maybe they could become a model. Until then it’s not the perfect model of society some believe.

Much to admire about Japan from the very basic long life expectancy but monetary sovereignty,

low inflation ,low unemployment have not delivered any kind of post growth template .

Wage stagnation for a long period.Acording to the OECD Japan rank 29 out of

34 on poverty.

What is missing? Egalitarian tax policies the vital component of the growth

in the middle classes in the post war settlement.

Twenty five years ago Japan was the top of the economic heap, the economic power to be reckoned with. It’s economic power was based on its international competitiveness and its drive to innovate. As with any increasingly successful economy, internal costs begin to rise. Incomes and labour rates rose strongly. And there goes the international trade advantage. Then at the same time China begins to open itself to the world and begins to be competitive in terms of innovation – it would automatically be competitive on cost. Japanese business even began to divert significant investment flows from domestic industry to China. So I would say these are the factors that have seen Japanese growth weaken. Of course the debt load from the post Tokyo property boom bust of the late 1980s was also a burden. When people talk of the Japanese economic performance of the last 25 years no-one seems to mention China and the diversion of domestic investment offshore but tend to focus on the failure of domestic monetary policy.

Dear Henry,

Twenty-five years ago (1991), signs of difficulty for the Japanese economy were already evident. Japan had been following an export-led growth model, and ran into external political problems. These problems led to the Plaza Accord (in 1985), which was explicitly designed to reduce Japan’s international trade advantage by altering its exchange rate against the dollar. It also, indirectly, led to the search for cheaper sources of labour, which gave a boost to neighbouring economies, like Taiwan and the PRC.

I would say that this exchange rate adjustment was a much more direct cause of the lost decade than any changes in labour incomes.

I’m new to this web site. Great posts, from yet another Austrialian ( in addition to Steve Keen!), who appreciates how the money supply is really created. I’ve got a back log of old posts to read through, but I’m looking forward to it. Cheers