I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The origins of the economic crisis

A good way to understand the origins of the current economic crisis in Australia is to examine the historical behaviour of key macroeconomic aggregates. The previous Federal Government claimed they were responsibly managing the fiscal and monetary parameters and creating a resilient competitive economy. This was a spurious claim they were in fact setting Australia up for crisis. The reality is that the previous government created an economy which was always going to crash badly.

The global nature of the crisis has arisen because over the last 2-3 decades most Western governments including the Australian government succumbed to the neo-liberal myth of budget austerity and introduced policies which allowed the destructive dynamics of the capitalist system to create an economic structure that was ultimately unsustainable. Once this instability began to manifest it was only a matter of time before the system imploded – as we are now seeing.

You can understand my take on this story by looking at the following graphs that I have put together (click on each graph for a larger version). This short blog is a summary of a major study I am conducting on this issue.

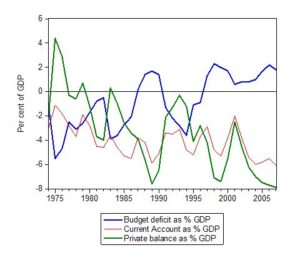

The first graph is the so-called “sectoral balances” which plots the Budget Deficit (-), the Current Account balance (- for deficit) and the private domestic balance (difference between Saving and Investment; – for deficit) as a per cent of GDP. The sectoral balances is another way of viewing the national accounts and provides empirical evidence for the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness. Consider the accounting identity drawn from the national accounts for the three sectoral balances:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The Equation says that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process.

The graph shows the sectoral balances for Australia. While the current account deficit has fluctuated with the commodity price cycle, it has continued to deteriorate slightly over the longer term. Accordingly, the dramatic shift from budget deficits to surpluses from the mid-1990s onwards has been mirrored by a corresponding deterioration in private sector indebtedness.

The only way the Australian economy could keep growing in the period after 1996 was for the private sector to finance increased spending via increased leverage. As I have explained in other blogs, this is an unsustainable growth strategy. Ultimately the private deficits will become so unstable that bankruptcies and defaults will force a major downturn in aggregate demand. Then the fiscal drag compounds the problem.

The solution is simple. The government balance has to be in deficit for the private balance to be in surplus given a relatively stable external balance. In terms of the slightly worsening current account deficit, we can interpret that as signifying an increased desire by foreigners to place their savings in financial assets denominated in Australian dollars. This desire means that that the foreign sector will allow us to enjoy more real goods and services from them relative to the real goods and services we have to export. We note that exports are always a “cost” while imports are “benefits”. As long as there is a foreign desire for our financial assets, the real terms of trade will provide net benefits to Australian residents which manifests as the current account deficit. An external deficit presents no intrinsic problem despite views by the orthodoxy to the contrary.

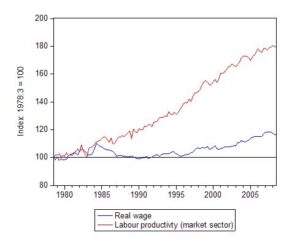

In the second graph you can see that real wages have failed to track GDP per hour worked (in the market sector) – that is, labour productivity. Real wages fell under the Hawke Accord era which was a stunt to redistribute national income back to profits in the vein hope that the private sector would increase investment. It was based on flawed logic at the time and by its centralised nature only reinforced the bargaining position of firms by effectively undermining the traditional trade union movement skills – those practised by shop stewards at the coalface. Under the Howard years, some modest growth in real wages occurred overall but nothing like that which would have justified by the growth in productivity. In March 1996, the real wage index was 101.5 while the labour productivity index was 139.0 (Index = 100 at Sept-1978). By September 2008, the real wage index had climbed to 116.7 (that is, around 15 per cent growth in just over 12 years) but the labour productivity index was 179.1.

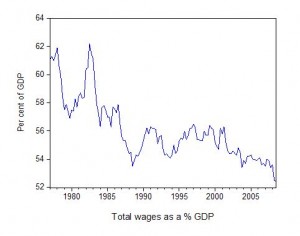

What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital. The Federal government (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the ways. The next graph depicts the summary of this gap – the wage share – and shows how far it has fallen over the last two decades.

The question then arises: if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself? This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector since around 1997.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold. But in the recent period, capital has found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals that we have read about constantly over the last decade or so.

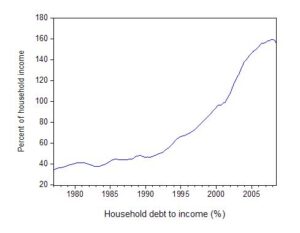

The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages. The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

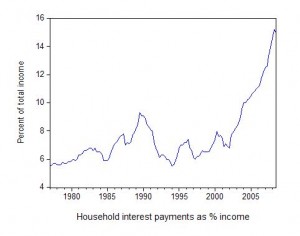

The next graphs shows various perspectives on the increasing household indebtedness in Australia. The left hand chart shows the spiralling in the debt to disposable income ratio which stood at 69.1 per cent in March 1996 and by September 2008 had risen to a staggering 156.1 per cent. It was often argued by the Government, the RBA and so-called financial industry experts during the build up period that there was no call for alarm because wealth was growing along with the debt. Well the debt was increasingly purchasing volatile assets other than housing and a fair proportion of the wealth created during that period has gone but the debt remains. The right hand chart shows the servicing burden (interest payments as a percentage of disposable income). This ratio has risen from 5.7 per cent in March 1996 to 15 per cent in September 2008, further squeezing the living standards of the household sector.

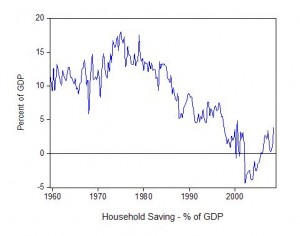

The problem with this strategy is that is was unsustainable. Household savings went negative as the government budgets went further into surplus. The next graph shows this clearly.

The only thing maintaining growth was the increasing credit which, of-course, left the nasty overhang – the precarious debt levels. I said years ago that this would eventually unwind as households realised they had to restore some semblance of security to their balance sheets by resuming their saving. Further, this increased precariousness of the household sector meant that small changes in interest rates and labour force status would now plunge them into insolvency much more quickly than ever before. Once defaults started then the triggers for global recession would fire and the malaise would spread quickly throughout the world. I was often criticised by conservatives and neo-liberal types for “crying wolf”. They kept harping on the fact that wealth was rising. Well the wealth has been severely diminished in the crisis but the nominal debt and the servicing commitments remain.

The return to deficits is the first step in recovery. Budget deficits finance private savings and are required if the household balance sheets are to remain healthy. Real wages also have to grow in proportion to labour productivity for spending levels to be maintained with sustainable levels of household debt. The household sector cannot dis-save for extended periods.

In designing the policy framework that will sustain growth in employment and reduce labour underutilisation these tenets have to be central. It also means that the massive executive payouts both in the private and public sector (including universities) have to be stopped and more realistic distributional parameters (more widely sharing the income produced) have to be followed.

Further, the first thing the Federal government should purchase is all the labour that no-one wants. By introducing a Job Guarantee they could offer a minimum wage to all those who wanted work and therefore restore full employment at a fraction of the investment they are proposing to make by way of fiscal stimulus.

Great blog! My only suggestion for future blogs on this theme would be , in regard to your comments about the move into riskier lending territory, to place more emphasis on:

(a) the efforts of the banking industry to convince respective national governments to further deregulate the finance sectors (e.g. repeal of Glass-Spiegel Act in the US and the deregulation policies maintained by the Blair and Brown governments in the UK);

(b) the inadequacies of Basel-II, which favoured both internal modeling techniques affording too much influence to easily-compromised ratings agencies, and dubious processes of generating securitised collateral, where the associated risk was on-sold to institutions situated outside the province of the heavily regulated trading bank sector.

I would also note that development models in 1960s and 1970s East Asia and early post-war Japan avoided the down-sides of such a debt-driven spending strategy through a combination of repressed-consumption and state-managed promotion of investment (an approach that is currently embraced by China).

Hello Bill,

Great article / blog which unfortunately would be beyond the scope of politicians or the reptiles that advise them upon economic and financial matters.

good times ahead I’m sure.

Dear Alan

Thanks for the comment. Blogs can be educative perhaps. I guess we will learn this the hard way but eventually we will learn it. The middle class are being levelled by this crisis and they are the ones that swing back and forth to substantiate paradigm changes.

best wishes, bill

Dear Bill,

“The middle class are being levelled by this crisis and they are the ones that swing back and forth to substantiate paradigm changes.”

If I read this correctly ,then by destroying the middle-class, neo-liberalism will be able to resist the paradigm change.

Cheers, Alan

Hi Professor Mitchell,

I am finding your blog very interesting and thought-provoking.

The reason for this post is that I have been following a different argument on the origins of the crisis presented by Andrew Kliman and Alan Freeman, which draws on Marx’s tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

(I realize this tendency stands or falls with Marx’s theory of value, but Kliman and Freeman are associated with the “temporal single-system interpretation” (TSSI) of Marx, which claims to have refuted existing critiques of Marx’s theory – their arguments are summarised by Kliman in his book Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency.)

I would be very interested in your opinion on Kliman’s argument.

Briefly, Kliman argues that capitalism cannot be set back on a sustainable high-growth course until profitability recovers to something like the level attained after the Great Depression and WWII – or at least until profitability recovers to levels well above those that have prevailed at the onset of each unsustainable recovery since the 1970s.

According to Kliman, in 1932 the rate of profit had sunk to -2%. By 1943, due to massive destruction of capital – both in value and physical terms – the rate of profit had risen to 30%. He argues that it was this strong revival in profitability that lay the basis for strong growth in the immediate post-war period.

Since then, however, the rate of profit has tended to recover, after crises, to lower and lower levels. According to Kliman, from 1941-1956, the rate of profit averaged 28%. From 1957-1980 it averaged 20%. From 1981-2004 it averaged 14%. The reason for the decline in profitability, he argues, is that governments have stepped in during crises (e.g. in the 1970s, early 1980s, and now) in an attempt to prevent the degree of capital destruction that occurred during the Great Depression and WWII, for obvious reasons. For Marx, the functional role of capitalist crises is to restore profitability, but this has not been allowed to occur sufficiently (in terms of the system’s requirements) – for political and, yes, humane reasons.

But in limiting the degree of capital destruction, Kliman argues, revival of profitability is also prevented, causing stagnationist tendencies that have been overcome only through unsustainable debt and the consequent creation of speculative bubbles.

In my view (though Kliman doesn’t argue this, at least in the link provided below), the ongoing vicious attacks on real wages and workers’ living conditions of the past thirty-five years or so can be regarded as an attempt by capitalists (and neoliberal governments) to prop up the rate of profit.

A more in-depth summary of Kliman’s argument can be found here:

http://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/2009/04/17/on-the-roots-of-the-current-economic-crisis-and-some-proposed-solutions/

alienated

The formula in the USA for the period 1980-2007 is really very simple (and it is what all “bailouts” and Fed money-printing are aimed at restoring): As productivity increases, real wages go down (that’s right, Virginia, “productivity” gains are always good for employers, but only good for employees if something makes the employers share those gains – which they really don’t want to do). The demand gap created by falling wages is filled (and demand is greatly expanded) by a big growth in consumer debt. You have reviewed it well, Bill. This process requires no specific government action other than to get out of the way (though in a starting environment like USA 1980, where there were existing government supports for wages and government restrictions on credit creation, pro-active government steps consisting of removing wage supports – including labor organizing laws – and removing credit creation restrictions, enhances the process).

In theory, if allowed to continue uninterrupted, as long as 1) lenders will lend to all who seek to borrow and 2) borrowers will borrow from all who will lend and 3) borrowers will make all their interest payments and 4) borrowers will repay all the principal or lenders will refinance all debt, then productivity can increase to 100% (assuming all goods and services are eventually produced by machines) and all the former wage earners will pay for all their consumer expenses with borrowed money. Total consumer debt will never go higher than GDP – in fact, the way GDP is measured increases in debt on the books (and all the financial activity to expand and service debt) raises GDP. This theory is part and parcel of neo-liberalism, which is not only inherently anti-government it is also inherently anti-labor (it is, in fact, only pro-capitalist – with an open worship of “entrepreneurs”). This whole model is not workable in the real world for too many reasons to discuss here, all of which would be obvious to a bright 6th-grader. In the USA the neo-liberal experiment from 1989-2007 first started breaking down (in the USA) toward the end of 2005 when the interest payments on debt undertaken by families to maintain or increase consumption reached levels of interest due higher than available income received (during the transition, people who had been taking home-equity loans to consolidate credit card debt started taking on additional credit card debt to meet their mortgage payments. “Financial innovation” (no-down payment loans, liar loans, interest-only loans, and zero-pay loans) only accelerated the credit ride up and the fall back down by loading up low-income families with big debts, it wasn’t necessary for the process to be unsustainable. The tipping point came when families couldn’t meet their interest payments – most commonly on mortgage debt, but only because paper-gains real estate equity extraction had become the primary form of debt expansion for consumer purchases. The rest is history, with the actual “credit crisis” (in which lending froze up and even when dethawed remained on a declining trajectory) coming only after consumer borrowing had gone into spasm. All the subsequent banking and commercial problems have resulted simply and directly from the reversal of the consumer debt growth that so wonderfully replaced wage growth for almost thirty years.

Looking forward, we ask “Will the governments – by bank and mortgage bailouts, or by money-printing, or by any other means, be able to restore the status quo ante as they so desperately desire”? The neo-liberal answer is yes, as soon as they get all the borrowing back to the level it was before. There is no room in the neo-liberal world for returning to wage growth, only for returning to credit growth (remember, “productivity is King”). Your model, Bill, as I understand it, points toward addressing wage growth rather than credit growth as a means to restore purchasing power and economic prosperity. I think you are on the more economically sound and socially healthier path, but sadly I don’t believe for a moment that any Anglo-American-Australian-type government will pay you any attention.

Regarding the explanation of the crisis that I mentioned above, Kliman has made available a new study on US corporate profitability and its connection (in his view) with crises, including the current one. It is still in draft form and can be found here (along with the data used in the study):

http://akliman.squarespace.com/persistent-fall/

The paper is long (about 27000 words). A brief summary of his findings can be found here:

http://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/2009/10/18/the-persistent-fall-in-profitability-underlying-the-current-crisis/

Bill and everybody,

would it be an objective point to start saying that wages as share of GDP should be 50% (or least never go below this point if we say that government is out there for all people) and then design public policies toward this objective? Like personal tax vs capital gain and corporate tax.

If yes then on this metric Australia still fares pretty well.

Income and wealth inequality develops by not rewarding labor for their productivity, as the professor has just shown us. It is the root cause of financial instability. Capital, and the need for capital must be balanced, for an economy to function stably.

If the accumulation of capital exceeds the need for capital to fund growth, the taxes on wealth and capital gains must be increased, and that on consumption and consumer income decreased .

If consumer demand, and the attendant capital needs, outpace capital accumulation, the reverse is required. Taxes then should be shifted from capital gains to consumption and consumer income.

Over the past several decades capital accumulation has outpaced the demand for capital, largely due to reductions in top bracket tax rates and stagnation of middle class incomes. The discussion that follows shows what happens when this occurs.

If too much capital is accumulated, rates of return on capital drop. As rates of return drop, capitalists seek ways to improve them through the use of leverage or through the use of techniques to increase the demand for credit.

If leverage is used , risk increases, necessitating even larger rates of return. This leads to a potentially unstable situation. So there is a limit to the amount of leverage that can be used.

As the limits of leverage are reached, investment banks and hedge funds will look for ways to stimulate demand for credit. This can be done by relaxing the standards for issuing credit, and compensating by using techniques to hide risk.

By collateralizing debt and issuing insurance on debt capitalists can be made to feel more comfortable with less secure investments. Debt issued with relaxed credit standards can be mixed with more secure debt making it harder for rating agencies to correctly assess risks. If regulation does not keep up with these measures, or decreases, the value of the collateralized assets and insurance instruments will be jeopardized.

Excess capital can also result in additional risky speculation. When returns on productive investments are low and approaching inflation levels, capitalists will be willing to take larger risks in short term speculation on valuable assets and commodities, causing prices to rise. In turn, the rise in prices creates an upward momentum in asset prices that attracts even more speculation. Such price bubbles tend to be self sustaining as more and more capitalists are willing to take advantage of the upward momentum in prices, until eventually that trend cannot be sustained and the bubbles burst.

All of these measures are driven by the need to increase returns on capital, when there is just too much capital for the real investment needs of the country. This is the situation that has developed over the last few decades largely because returns have been going more and more to capitalists while workers wages have stagnated. With stagnating wages, the demand for goods and services has not kept up with the accumulation of capital.

The stagnation of wages has caused consumers to seek returns in the financial sector and to tap available credit to sustain consumption. This is evidenced by the excessive growth of the financial sector. At the same time, high income and capital gains tax rates have been reduced, accelerating the income and wealth gap between capitalists and middle class consumers.

Unless taxes are shifted to wealth and capital gains from consumption and consumer incomes, this increasing spread in income and wealth will continue to cause instability and the kind of financial crises we are now experiencing.

Future references:

http://voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/5823

Debt, deleveraging, and the liquidity trap – krugman

*****

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=13193

When will the workers wake up?

*****

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=13206

Saturday Quiz – January 22, 2011 – answers and discussion (Wage Share)

*****

bill, I like how I can add to a post this far in the future. Thanks for that!!!

More Future References:

*****

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/04/28/where-the-productivity-went/

Where The Productivity Went

*****

http://www.epi.org/publication/ib330-productivity-vs-compensation/

The wedges between productivity and median compensation growth

By Lawrence Mishel | April 26, 2012

“Conclusion

Productivity growth has frequently been labeled the source of our ability to raise living standards. This is sometimes what is meant by the call to improve our “competitiveness.” In fact, higher productivity is an important goal, but it only establishes the potential for higher living standards, as the experience of the last 30 or more years has shown. Productivity in the economy grew by 80.4 percent between 1973 and 2011 but the growth of real hourly compensation of the median worker grew by far less, just 10.7 percent, and nearly all of that growth occurred in a short window in the late 1990s. The pattern was very different from 1948 to 1973, when the hourly compensation of a typical worker grew in tandem with productivity. Reestablishing the link between productivity and pay of the typical worker is an essential component of any effort to provide shared prosperity and, in fact, may be necessary for obtaining robust growth without relying on asset bubbles and increased household debt. It is hard to see how reestablishing a link between productivity and pay can occur without restoring decent and improved labor standards, restoring the minimum wage to a level corresponding to half the average wage (as it was in the late 1960s), and making real the ability of workers to obtain and practice collective bargaining.”

*****

Try putting more people into retirement to tighten up the labor market.

And even more future references:

Debt inequality is the new income inequality

By Tami Luhby @CNNMoney May 2, 2012: 5:26 AM ET

http://money.cnn.com/2012/05/02/news/economy/income-debt-inequality/index.htm

*****

Debt Serfdom in One Chart

The essence of debt serfdom is debt rises to compensate for stagnant wages. (probably should be real wages)

Friday, May 04, 2012

http://charleshughsmith.blogspot.com/2012/05/debt-serfdom-in-one-chart.html

plus the Doug Short chart

*****

Leveraging Inequality

Finance & Development, December 2010, Vol. 47, No. 4

Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2010/12/Kumhof.htm

At end, “Restoring equality by redistributing income from the rich to the poor would not only please the Robin Hoods of the world, but could also help save the global economy from another major crisis.”

No mention of banking/hedge fund in there. Replace major crisis with a too much debt crisis. Too much gov’t debt and too much private debt are both medium of exchange problems. Increasing the amount of medium of exchange while having a zero private debt and zero public debt economy helps allow productivity gains and other things to be evenly distributed between the major economic entities and evenly distributed in time. It also helps to eliminate:

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t (preferably with debt) plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (preferably with debt)

And, also helps to eliminate the idea that the amount of medium of exchange in circulation can fall due to debt defaults and/or debt repayments.

Those are all problems from targeting price inflation and/or NGDP and assuming real aggregate demand is unlimited and doing nothing else.

And again more future references:

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/06/fed-survey-from-2007-to-2010-median.html

From the Federal Reserve: Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2007 to 2010: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances (ht MS)

http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2012/pdf/scf12.pdf

“The Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) for 2010 provides insights into changes in family income and net worth since the 2007 survey. The survey shows that, over the 2007-10 period, the median value of real (inflation-adjusted) family income before taxes fell 7.7 percent; median income had also fallen slightly in the preceding three-year period. The decline in median income was widespread across demographic groups, with only a few groups experiencing stable or rising incomes.”

And, “The decreases in family income over the 2007−10 period were substantially smaller than the declines in both median and mean net worth; overall, median net worth fell 38.8 percent, and the mean fell 14.7 percent (figure 2).Median net worth fell for most groups between 2007 and 2010, and the decline in the median was almost always larger than the decline in the mean. The exceptions to this pattern in the medians and means are seen in the highest 10 percent of the distributions of income and net worth, where changes in the median were relatively muted. Although declines in the values of financial assets or business were important factors for some families, the decreases in median net worth appear to have been driven most strongly by a broad collapse in house prices.”

And, “The only group (by income) with an increase in the median net worth was the top 10%. There is much more in the survey.”

Yet another future reference:

http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2012/06/guest_contribut_19.html

Guest Contribution: “Labor Shares and Corporate Savings”

“The stability of the labor share, the proportion of an economy’s total income paid out to workers as compensation for their time, has long stood as one of the principal stylized facts of economic growth. While this regularity may very well hold across centuries or in the long run, our recent work demonstrates the failure of this characterization over the last three decades. In “Declining Labor Shares and the Global Rise of Corporate Savings,” (Karabarbounis and Neiman, 2012) we show that labor shares have eroded in most countries around the world, including seven of the eight largest. Globally, corporations paid about 65 percent of their income to labor (as opposed to capital) in 1975, compared with about 60 percent in 2007.1 This trend can be seen in the red dashed line in Figure 1, which plots year fixed effects from a regression of labor shares each year in the eight largest economies that also absorbs country fixed effects.2″

“Changes in the labor share have broad implications for inequality and for our understanding of how firms operate. We also demonstrate that the labor share declines were associated with increases in corporate profits and corporate savings, which equal the portion of profits which were not paid out as dividends. Indeed, all eight of the world’s largest economies saw an increase in the share of their total savings originating in the corporate sector rather than from households or the government. Corporate savings accounted for a minority of total global savings in 1975 but contributed a majority by 2007. The upward sloping black line in Figure 1 plots year fixed effects from a regression of the share of total savings due to the corporate sector in the eight largest economies after absorbing country fixed effects. The increase of more than 20 percentage points is striking. In essence, thirty years ago global investment was primarily funded by household savings whereas now it is primarily funded by the savings of corporations.

What caused these trends? …”

Some more!

Wages aren’t stagnating, they’re plummeting

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/wp/2012/07/31/wages-arent-stagnating-theyre-plummeting/

Higher productivity doesn’t mean higher wages

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/wp/2012/08/10/higher-productivity-doesnt-mean-higher-wages/

I think that it is cool that ‘Fed Up’ continues to add info here! 🙂

Back again.

Majority of New Jobs [in the USA] Pay Low Wages, Study Finds

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/31/business/majority-of-new-jobs-pay-low-wages-study-finds.html

It starts with:

“While a majority of jobs lost during the downturn were in the middle range of wages, a majority of those added during the recovery have been low paying, according to a new report from the National Employment Law Project.

The disappearance of midwage, midskill jobs is part of a longer-term trend that some refer to as a hollowing out of the work force, though it has probably been accelerated by government layoffs.

“The overarching message here is we don’t just have a jobs deficit; we have a ‘good jobs’ deficit,” said Annette Bernhardt, the report’s author and a policy co-director at the National Employment Law Project, a liberal research and advocacy group.”

Wekasus, thank you! I hope you find the posts informative and useful.

Thanks to bill for allowing posts this far in the future and an ongoing discussion.

Still at it.

Labor Day, Income & The Middle Class

Charts:

MEDIAN INCOME

PERCENTAGE OF OVERALL US INCOME

SIZE OF MIDDLE CLASS

COSTS OF MIDDLE CLASS LIFESTYLE

MIDDLE CLASS DEBT LEVELS

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2012/09/the-middle-class/

Still more to be done!

PRIVATE Debt Is the Main Problem

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2012/09/private-debt-is-the-main-problem/

I believe gov’t debt can be a problem too.

Will it ever end?

Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011

http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/income_wealth/cb12-172.html

“In 2011, real median household income was 8.1 percent lower than in 2007, the year before the most recent recession, and was 8.9 percent lower than the median household income peak that occurred in 1999. The two percentages are not statistically different from one another.”

Behind the Decline in Incomes

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/12/behind-the-decline-in-incomes/

“4. There’s more evidence that the work force is “hollowing out,” as there was significant job growth in the first, second and fifth income quintiles, but not in the third and fourth ones.”

Average Hourly Earnings:

Deciphering Historical Trends

http://advisorperspectives.com/dshort/commentaries/Average-Hourly-Wage-Trends.php

The End of the Middle Class Century: How the 1% Won the Last 30 Years

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/the-end-of-the-middle-class-century-how-the-1-won-the-last-30-years/262221/

The IMF should not exist, and I don’t agree with everything here but …

http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2012/09/13/united-states-how-inequality-affects-saving-behavior/

“Saving patterns before the crisis

To analyze individual household behavior, we used the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, a well-established dataset that collects data from the same households over time. Our key finding is that that households with consistently lower income growth experienced larger declines in their saving rates and a larger rise in their MORTGAGE [MY emphasis & most likely from a BANK] debt before the crisis. We also find that these types of households contributed significantly to the overall decline in the saving rate.

For instance, the households with the bottom third of income growth over 1999-2007 accounted for half of the decline in the overall saving rate over the same period. This finding is surprising because economic theory would predict that households save less when their income falls temporarily, but not when the fall is highly persistent [NOT if economists & politicians tell them things will get better]. By contrast, we don’t find a large decline in the saving rates of families with consistently lower income levels; their saving rates have always been lower than the saving rates of higher income families.

Our results suggest that households with disappointing income growth attempted to preserve their living standards in the boom years by tapping into their housing equity [WAGES not keeping up with prices? , monthly budgeting].

Their decisions did not anticipate the impending correction in house prices, the weaker economy, and lower incomes.The easy availability of home equity financing allowed households with low income growth to at least temporarily “keep up with the Joneses”; in other words, consumption inequalities remained smaller than income inequalities. With the subsequent housing crash, those households already suffering from lowest income growth found themselves more vulnerable, with high levels of debt [MORE monthly budgeting].

Another interesting finding is that the decline in saving rates was larger for households with bottom third of income growth than for those who experienced the top third of house price increases. On the basis of this finding, it seems worth examining further whether the decline in the saving rate prior to the crisis reflects more the declining opportunities-GRASPING FOR THE LAST STRAW TO PREVENT DECLINING LIVING STANDARDS (MY emphasis)-rather than the story of winners in the “housing lottery” consuming their windfalls.

Saving patterns after the crisis

How did households fare after the crisis?

We found that those more dependent on housing wealth and those with higher debt levels on the eve of the crisis indeed raised their savings sharply after the crisis. Yet, as this sharp correction started from very depressed and even negative saving rates, these households have not yet made meaningful progress in reducing debt and repairing their balance sheets. Hence, these households may face grim future consumption prospects.

Taken together, our results do suggest that the lower income growth for segments of the income distribution was linked to the drop in saving rates and growing indebtedness of American families. Moreover, households that entered the crisis with a more precarious wealth situation have made limited progress in rebuilding their net worth (the difference between household financial and nonfinancial assets and their debt) by actively saving out of their incomes.

Recent data on household finances indeed show that at least half of the American families had lower net worth (in inflation-adjusted terms) in 2010 than they did two decades ago (the median American family in 2010 had a net worth of $77,000, compared with $126,000 in 2007 and $79,000 in 1989).

The data also shows that the share of the population that saved any of their income dropped from 54.6 percent to 52 percent between 2007 and 2010.

Unless their incomes and house prices pick up robustly, many households will need sustained levels of higher savings to rebuild wealth, making it less likely for the American consumer to drive U.S. growth.”

A few more …

Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six

http://www.voxeu.org/article/us-economic-growth-over

Hard Times Come Again Once More

http://www.economicprincipals.com/issues/2012.09.23/1419.html

Hard Times??? My FOOT!

If the economic situation was handled correctly, there should be very little of the “Hard Times”!

Your a trooper Fed Up! 🙂

And some more…

http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/commentary/2012/2012-13.cfm

http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/trends/2012/0212/01gropro.cfm

Left out the titles for the ones just above (12:35).

Labor’s Declining Share of Income and Rising Inequality

— some talk about Labor Income & Capital Income

Behind the Decline in Labor’s Share of Income

All stakeholders should be involved. From:

Higher Wages Are The Key to Rebuilding the American Dream: Pulitzer-Prize Winning Reporter

http://finance.yahoo.com/blogs/daily-ticker/key-growing-economy-pay-workers-more-says-hedrick-155918542.html

Sort of related to productivity & too much debt. Pimco is actually part of the problem but …

More People Over 65 Are Still Working

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2012/10/08/more-people-over-65-are-still-working/

What’s Your Number at the Zero Bound? (Has to do with retirement)

http://www.pimco.com/EN/Insights/Pages/Whats-Your-Number-at-the-Zero-Bound.aspx

Time for Some More

The Uncomfortable Truth About American Wages

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/22/the-uncomfortable-truth-about-american-wages/

“This finding of stagnant wages is unsettling, but also quite misleading. For one thing, this statistic includes only men who have jobs. In 1970, 94 percent of prime-age men worked, but by 2010, that number was only 81 percent. The decline in employment has been accompanied by increases in incarceration rates, higher rates of enrollment in the Social Security Disability Insurance program and more Americans struggling to find work. Because those without jobs are excluded from conventional analyses of Americans’ earnings, the statistics we most commonly see – those that illustrate a trend of wage stagnation – present an overly optimistic picture of the middle class.

When we consider all working-age men, including those who are not working, the real earnings of the median male have actually declined by 19 percent since 1970. This means that the median man in 2010 earned as much as the median man did in 1964 – nearly a half century ago. Men with less education face an even bleaker picture; earnings for the median man with a high school diploma and no further schooling fell by 41 percent from 1970 to 2010.

Women have fared much better over these 40 years, but they started from a lower level, and the same problems faced by their male counterparts are beginning to have an effect. Since 1970, the earnings of the median female worker have increased by 71 percent, and the share of women 25 to 64 who are employed has risen to 71 percent, from 54 percent. But after making significant wage gains over several decades, that progress has slowed and even reversed recently. Since 2000, the earnings of the median woman have fallen by 6 percent.”

Some talk about the “jobs” recovery in the USA:

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2012/11/explosion-in-uncovered-employment.html

“Covered employment is the set of working employees that have unemployment benefits.”

And, “I added data points to Tim’s chart. Let’s do the math.

According to the BLS, the economy added 4,951,000 since January 2009. In the same timeframe, uncovered employment rose by 6,573,468! The difference is 1,622,468.

Got that?

133% of the jobs created since January 2009 are not covered. Employment rose by less than 5 million while uncovered employment rose by over 6.5 million.”

This Time is Different, Again? The United States Five Years after the Onset of Subprime

Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff

http://www.scribd.com/fullscreen/110191703?access_key=key-1gvz59t1cbvkq7nqew4l

*****

The Middle Class Is Worse Off Than You Think: Michael Greenstone

http://finance.yahoo.com/blogs/daily-ticker/middle-class-worse-off-think-michael-greenstone-133855510.html

*****

Finding Jobs, But Working For Less Pay

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/finding-jobs-working-less-pay-010500333.html

*****

Tax Cuts for the Wealthiest Don’t Stimulate the Economy: Report

http://finance.yahoo.com/blogs/daily-ticker/tax-cuts-wealthiest-don-t-stimulate-economy-report-160714639.html

http://graphics8.nytimes.com/news/business/0915taxesandeconomy.pdf

*****

Retirement Plan Shift Is Creating a Generation of Workers Unable to Retire

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/retirement-plan-shift-is-creating-a-generation-of-workers-unable-to-retire.html

Is it possible that there is wealth/income inequality for businesses too?

Meet the Four Companies That Together Provided Most of 2012 Earnings Growth in the S&P 500

Apple, AIG, Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2012/11/26/apple_aig_goldman_sachs_and_bank_of_america_provided_most_of_2012_s_earnings.html

Jobs, Productivity and the Great Decoupling

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/12/opinion/global/jobs-productivity-and-the-great-decoupling.html?_r=0

“The Great Decoupling is not going to reverse course, for the simple reason that advances in digital technologies are not about to stop. In fact, we’re convinced that they are accelerating. And this should be great news for society. Digital progress lowers prices, improves quality, and brings us into a world where abundance becomes the norm.

But there is no economic law that says digital progress will benefit everyone evenly. As technology races ahead it can leave a lot of workers behind. In the short run we can improve their prospects greatly by investing in infrastructure, reforming education at all levels and encouraging entrepreneurs to invent the new products, services and industries that will create jobs.

While we’re doing this, however, we also need to start preparing for a technology-fueled economy that’s ever-more productive, but that just might not need a great deal of human labor. Designing a healthy society to go along with such an economy will be the great challenge, and the great opportunity, of the next generation.

We have to acknowledge that the old ride of tightly coupled statistics has ended, and start thinking about what we want the new ride to look like.”

New ride might look like more retirement?

I agree with some but not all of this:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2012/12/01/the-debt-issue-in-neoclassical-economics/

Krugman’s Explanation of Stagnant Real Wages

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2012/12/krugmans-explanation-of-stagnant-real-wages.html

“Another reader made a similar criticism: “The argument depends on the theory that workers are paid their marginal product. Some people hold to this old idea, however it is not supported by the empirical evidence.” Amen.

For further discussion of criticisms of marginal productivity theory (a two part paper), see here and here.”

http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue59/Moseley59.pdf

http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue61/Moseley61.pdf

“It is time we stop talking about marginal products and look for other better, logically consistent and empirically supported theories of the distribution of income.

I agree with Krugman in a subsequent post where he stated: “If you want to understand what’s happening to income distribution in the 21st century, you need to stop talking so much about skills, and start talking much more about profits and who owns the capital.”

But marginal productivity theory is not a coherent way to talk about profits.

Fred Moseley

Mount Holyoke College”

Richard Koo Debunks the “Deleveraging is Almost Done, American Consumer Getting Ready for Good Times” Meme

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/01/richard-koo-debunks-the-deleveraging-is-almost-done-american-consumer-getting-ready-for-good-times-meme.html

“And the implications…

The answer can also be found in Figure 1:the fact that the latest white bar is below zero means households drew down financial assets in the quarter. And that is hardly a good sign. It has happened only three times since 2000, including the present occasion.

The first instance (barely visible in the graph) was in 2000 Q4, when the Internet bubble collapsed. The second was in 2008 Q4, when the failure of Lehman Brothers sparked a global financial crisis. People faced cash flow problems in both periods andprobably were forced to draw down existing savings to make necessary payments.

During the bubble period towards the middle of Figure 1, much attention was paid to the fact that the US household savings rate had turned negative. While the sector did run a financial deficit during this period, the deficit was attributable to the fact that the increase in financial liabilities (ie growth in borrowing) was greater than the increase in financial assets (ie growth in savings). There was no drawdown of financial assets.

Hence we need to pay attention to the fact that the latest figure shows only the third drawdown of financial assets since 2000 and that this drawdown is responsible for the financial deficit in the broader household sector. The reason: if household consumption is being financed by the drawdown of financial assets, it is not likely to be sustainable.”

Median Household Incomes: Down 0.5% in 2012

http://advisorperspectives.com/dshort/updates/Median-Household-Income-Update.php

“Overview: The Sentier Research monthly median household income data series is now complete through 2012. Nominal household incomes rose 1.3% for the calendar year, but adjusted for inflation, household incomes declined by 0.5%. Real household incomes have essentially been flat for the past seven months and are down 7.9% thus far in the 21st century.”

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2013/01/job-growth-productivity-and-labor-force-2/

20 Years – Net Job Creation , Labor Productivity , Labor Force Participation Rate

See chart(s) there.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-27/what-bernanke-didn-t-say-about-housing.html

“What Bernanke Didn’t Say About Housing”

“One of the more interesting exchanges at Ben Bernanke’s testimony to the Financial Services Committee today was the one between the Federal Reserve chairman and Representative Scott Garrett, a Republican from New Jersey.

Citing Bernanke’s assertion that one of the benefits of QE had been the rise in home prices, Garrett said the following:

“Previously you have said that the Fed’s monetary policy actions earlier this decade, 2003 to 2005, did not contribute to the housing bubble in the U.S. So which is it? Is monetary policy by the Fed not a cause of inflationary prices of housing, as you said in the past? Or is it a cause of inflating prices of housing? Can you have it both ways?”

“Yes,” Bernanke said, much to Garrett’s surprise. The increase in home prices now is justified by the low level of mortgage rates, he said. On the other hand, those rates averaged 6 percent in the early part of the last decade and “can’t explain why house prices rose as much as they did.”

What he didn’t say was that the percentage of adjustable-rate mortgages soared to a record 37 percent of total mortgage volume in 2005. From mid-2003 to mid-2006, ARM volume averaged 30 percent. The interest rate on ARMs is priced off the Fed’s overnight rate. It was this type of loan that witnessed the most egregious underwriting abuses and the highest delinquency and foreclosure rates.

Garrett 1, Bernanke 0.

Garrett wasn’t finished. He asked Bernanke about another presumed benefit of QE: higher stock prices.

“I’m sure you’re familiar with Milton Friedman’s work that says that people only really consume off of their permanent income, which basically means that you don’t consume — increase consumption — because your stocks have gone up in the marketplace,” Garrett said, before wandering off into areas such as how seniors should invest, “risk-taking” and “price discovery” in a market distorted by the Fed.

These are all good questions. I’ve asked many of them myself, most recently in my column today. The Fed is convinced it has the tools, regulatory wherewithal and forecasting acumen to prevent a misallocation of credit, better known as an asset bubble, with the potential to destabilize the financial system.

Like Congressman Garrett, I’m not so sure.”

Back for more:

What Happened to Wages?

Below are five data graphics from my new book An Illustrated Guide to Income in the United States (pgs 106, 108, 109, 110, 112) that shows the long-term growth in wages in the US.

http://visualizingeconomics.com/blog/2013/3/4/wages

And,

The U.S. Economy in the 1920s

http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/smiley.1920s.final

“Earnings for laborers varied during the twenties. Table 1 presents average weekly earnings for 25 manufacturing industries. For these industries male skilled and semi-skilled laborers generally commanded a premium of 35 percent over the earnings of unskilled male laborers in the twenties. Unskilled males received on average 35 percent more than females during the twenties. Real average weekly earnings for these 25 manufacturing industries rose somewhat during the 1920s. For skilled and semi-skilled male workers real average weekly earnings rose 5.3 percent between 1923 and 1929, while real average weekly earnings for unskilled males rose 8.7 percent between 1923 and 1929. Real average weekly earnings for females rose on 1.7 percent between 1923 and 1929. Real weekly earnings for bituminous and lignite coal miners fell as the coal industry encountered difficult times in the late twenties and the real daily wage rate for farmworkers in the twenties, reflecting the ongoing difficulties in agriculture, fell after the recovery from the 1920-1921 depression.”

“The shift from coal to oil and natural gas and from raw unprocessed energy in the forms of coal and waterpower to processed energy in the form of internal combustion fuel and electricity increased thermal efficiency. After the First World War energy consumption relative to GNP fell, there was a sharp increase in the growth rate of output per labor-hour, and the output per unit of capital input once again began rising. These trends can be seen in the data in Table 3. Labor productivity grew much more rapidly during the 1920s than in the previous or following decade. Capital productivity had declined in the decade previous to the 1920s while it also increased sharply during the twenties and continued to rise in the following decade.”

Table 3 says 5.44% growth 1919 to 1929.

Keywords for last post:

1920 , 1920’s , 1924 , 1927 , 1929

This does not help monthly budgets.

U.S. Health Care Prices Are the Elephant in the Room

By UWE E. REINHARDT

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/29/u-s-health-care-prices-are-the-elephant-in-the-room/

Census Bureau: More renters with high housing costs

http://www.housingwire.com/fastnews/2013/04/16/census-bureau-more-renters-high-housing-costs

“The number of U.S. households that rent rather than own a home rose from 34.1% in 2009 to 35.4% in 2011. Nearly 25% of the nation’s metros saw a rise in renting households, while less than 3% saw a drop.

The study revealed that more renters are spending a high percentage of their income on rent. In this report, renters spending 35% or more of household income on rent and utilities are considered to have high rental costs.

The number of renters with high housing costs in the U.S. increased from 42.5% in 2009 to 44.3% in 2011. However, average rental rates in the U.S. declined during the same time period.

“While we saw a decrease in rental vacancy rates and pricing in some areas, the burden of rental costs on households increased across many parts of the nation,” said Arthur Cresce, assistant division chief for housing characteristics at the Census Bureau.

He added, “Factors such as supply and demand for rental housing and local economic conditions play an important role in helping to explain these relationships.””

Not helping the monthly budget.

http://advisorperspectives.com/dshort/guest/Lance-Roberts-130509-Labor-Hoarding.php

“Of course, one of the highest “costs” to any business is labor. One way that we can measure this view is by looking at corporate profits on a per employee basis. Currently, that ratio is at the highest level on record.”

“However, the mistake is assuming that just because initial claims are declining that the economy, and specifically full-time employment, is markedly improving. The next chart shows initial jobless claims versus the full-time employment-to-population ratio.”

“The current detachment between the financial markets and the real economy continues. The Federal Reserve’s interventions continues to create a wealth effect for market participants, however, it is unfortunate that such a wealth effect is only enjoyed by a small minority of the total population – and it is primarily those at the upper end of the pay scale that have jobs.”

Debating Doctors’ Compensation

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/24/debating-doctors-compensation/

May Employment Report Offers Little Cause for Celebration

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2013/06/may-employment-report-offers-little-cause-for-celebration/

“The greatest issue plaguing the U.S. economic recovery is the dismal pace of real income and wage growth. As long as incomes do not keep up with the underlying rate of inflation, the economy cannot manage enough growth to foster job creation. Average hourly earnings were unchanged in May, and only 2 percent higher than year ago levels. In other words, consumers are simply running in place. This is particularly frustrating for those at the lower end of the income spectrum.

According to the report, 96,300 of the 175,000 new nonfarm jobs created last month were in very low wage industries (retail, 27,000), temporary, (25,600), leisure and hospitality (43,000). The industries with the two lowest hourly wages are leisure and hospitality at $11.76 per hour and retail at $13.92 per hour. Even more concerning is that many of these positions are being filled by older, formerly retired persons who are taking away employment opportunities for young people. The unemployment rate for teenagers (16 to 19 years) increased to 24.5 percent in May from 24.1 percent in April.

This is not a social judgment; it’s economics. That middle income strata – the primary driver of the U.S. economy – has fallen to the low income, and the low income has plunged to poverty. Now it’s just the “haves” in the driving seat, and once the stock market gets hit, it will fall down a rung too.”

Not Just May Employment

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/raskin20130322.htm

“About two-thirds of all job losses resulting from the recession were in moderate-wage occupations, such as manufacturing, skilled construction, and office administration jobs. However, these occupations have accounted for less than one-quarter of subsequent job gains. The declines in lower-wage occupations–such as retail sales and food service–accounted for about one-fifth of job loss, but a bit more than one-half of subsequent job gains. Indeed, recent job gains have been largely concentrated in lower-wage occupations such as retail sales, food preparation, manual labor, home health care, and customer service.3

Furthermore, wage growth has remained more muted than is typical during an economic recovery. To some extent, the rebound is being driven by the low-paying nature of the jobs that have been created. The slow rebound also reflects the severe nature of the crisis, as the slow wage growth especially affects those workers who have become recently re-employed following long spells of unemployment. In fact, while average wages have continued to increase steadily for persons who have remained employed all along, the average wage for new hires have actually declined since 2010.”

Got some more:

Wage deflation charts of the day

http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2013/07/09/wage-deflation-charts-of-the-day/

“This chart shows where a lot of the current stock-market strength is coming from: capital is taking more than 100% of real productivity gains, with labor steadily losing out. This, I fear, is the New Normal: OK for investors, bad for workers.”

This chart refers to Figure 1.

Occupational Employment and Wages News Release

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ocwage.htm

With more:

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2013/08/is-mckinsey-to-blame-for-skyrocketing-ceo-pay/

“Anyone who has worked in the corporate milieu knows that the arrival of McKinsey on the scene tends to not be a sign of good news for the rank and file. What is less known is McKinsey’s role in the creation of the CEO-to-worker gap itself. In 1951, General Motors hired McKinsey consultant Arch Patton to conduct a multi-industry study of executive compensation. The results appeared in Harvard Business Review, with the specific finding that from 1939 to 1950, the pay of hourly employees had more than doubled, while that of “policy level” management had risen only 35 percent. If you adjusted that for inflation, top management’s spendable income had actually dropped 59 percent during the period, whereas hourly employees had improved their purchasing power.”

And, “Crony capitalism and the transfer of wealth from shareholders to insiders goes back much further than you may have guessed.

Good ideas gradually die of their own accord, replaced with better ones. Bad ideas have a death grip on society, often with wealthy sponsors benefiting from them. That’s why they seem to hang around forever…”

http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/nyt-warns-of-a-looming-crises-in-germany-rising-wages

“Simple arithmetic shows that the impact of productivity growth will swamp the impact of demographics.”

Auto leasing surges to record high

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101003126

“Todd Skelton, who oversees AutoNation dealerships in Palm Beach and Broward County, Florida, said customers are now hunting for the lowest monthly payment with a new car or truck, and often that means taking out a lease.

“People are much more open-minded about leasing. Nowadays, almost any make or model can be leased and that’s attractive to a lot of customers,” noted Skelton.

Leasing comeback with auto rebound

Three years ago, just 17.7 percent of vehicles bought with financing were leased.

But leasing has soared since then due to a combination of more aggressive leasing offers by automakers and buyers searching for the best option to keep monthly payments in check amid rising new car and truck prices.

“Manufacturers have enhanced their lease options so leasing is often a better deal than financing with a loan,” Skelton added.”

Hello to the monthly payment consumer from the 1920’s!!!

A Decade of Flat Wages

The Key Barrier to Shared Prosperity and a Rising Middle Class

http://www.epi.org/publication/a-decade-of-flat-wages-the-key-barrier-to-shared-prosperity-and-a-rising-middle-class/

“The nation’s economic discourse has finally shifted from talk of “grand bargain” budget deals to a focus on addressing the economic challenges of the middle class and those aspiring to join the middle class. Growing the economy from the “middle out” has become the new frame for discussing economic policy. This is long overdue; in our view, an economy that does not provide shared prosperity is, by definition, a poorly performing one. Further, such an economy will not provide sustainable growth without relying on consumption fueled by asset bubbles and escalating household debt. The collapse of the housing bubble and the ensuing Great Recession have laid bare the consequences of this model of unbalanced growth.

The revived discussion of strengthening the middle class, however, has so far failed to drill down to the central problem: The wage and benefit growth of the vast majority, including white-collar and blue-collar workers and those with and without a college degree, has stagnated, as the fruits of overall growth have accrued disproportionately to the richest households. The wage-setting mechanism has been broken for a generation but has particularly faltered in the last 10 years, once the robust wage growth of the late 1990s subsided. Corporate profits, on the other hand, are at historic highs. Income growth has been captured by those in the top 1 percent, driven by high profitability and by the tremendous wage growth among executives and in the finance sector (for more on wage and income growth among the top 1 percent, see Bivens and Mishel 2013).

President Obama’s July 24 speech in Galesburg, Ill., marking the kickoff of the White House’s “A Better Bargain for the Middle Class” initiative, illustrates both the best of this recent focus on the middle class and the failure to adequately acknowledge and address the economy’s failure to broadly raise wages. The president appropriately looked back in time, noting:

In the period after World War II, a growing middle class was the engine of our prosperity. Whether you owned a company, swept its floors, or worked anywhere in between, this country offered you a basic bargain-a sense that your hard work would be rewarded with fair wages and benefits, the chance to buy a home, to save for retirement, and, above all, to hand down a better life for your kids.

And he correctly identified what broke down:

But over time, that engine began to stall. That bargain began to fray. . . . The link between higher productivity and people’s wages and salaries was severed-the income of the top 1 percent nearly quadrupled from 1979 to 2007, while the typical family’s barely budged.”

The myth of the modern welfare queen (TANF)

http://www.cnbc.com/id/100975718

“An average of about 1.72 million families a month received direct assistance through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families last year, according to the latest data from the federal government’s Office of Family Assistance. That’s about half the 3.94 million families who received TANF in 1997, according to an Urban Institute report funded by the Department of Health and Human Services

In addition, about 62 percent of never-married moms ages 20 to 49 with a high school degree or less were working in 2011, according to an analysis of Current Population Survey data prepared by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal-leaning think tank. That’s up from about 51 percent in 1992 but down from 76 percent in 2000, before two recessions hit low-skill workers hard.

Welfare-to-work

Welfare has not been the same since the mid-1990s, when the old program, called Aid to Families with Dependent Children, was replaced by TANF. The new program’s requirements include that recipients do 20 to 30 hours a week of work-related activities, such as job hunting or community service.

Most states allow adults to collect TANF for a maximum of five years over the course of their lifetime.

(Read more: Most would keep job after lottery win)

“The expectation is that you need to be looking for work,” said LaDonna Pavetti, vice president for family income support policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “And if you don’t, you will either have your benefits reduced or lose them entirely.”

Many more low-educated single mothers did start working soon after the program was introduced, but experts say welfare-to-work cannot take all the credit for that. The late-1990s welfare reform effort also coincided with the expansion of the earned income tax credit-which provides financial assistance to low-wage workers-and a strong labor market.

“There really were three factors: One was welfare reform, one was expansion of the EITC, and one was (the) economy,” Pavetti said. “Welfare reform was not the biggest role in that.”‘

Working, but struggling

These days, Kathryn Edin, a professor of public policy at Harvard University, said the good news is that many single mothers who used to be longer-term welfare recipients are now workers who need assistance only once in a while.

But the bad news for those with little education and low skills is that, in the past decade or so, it has become increasingly difficult to find a stable, full-time job that pays well. That means some moms may now be working very hard and still find that their families are at or near poverty.

A person working a full-time, minimum wage job would take home $15,080 a year. That’s below than the Census Bureau’s 2012 poverty threshold for a family of one adult and two children under 18.”

$7.25 per hour [federal minimum wage] times 40 hours per week times 52 weeks per year = $15,080 per year

Between 2000 and 2012, American wages grew…not at all

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/08/21/between-2000-and-2012-american-wages-grewnot-at-all/

“Get a load of that productivity line, and how much steeper it is than the compensation lines. That’s not supposed to happen, and for many decades, it wasn’t. In 1996, Paul Krugman observed that from 1977-1992, “the increases in productivity and compensation have been almost exactly equal. But then how could it be otherwise? Any difference in the rates of growth of productivity and compensation would necessarily show up as a fall in labor’s share of national income – and as everyone who is even slightly familiar with the numbers knows, the share of compensation in U.S. national income has been quite stable in recent decades.” That was true when Krugman wrote it. It’s not true anymore. Labor’s share of national income is experiencing a serious fall. The benefits of productivity growth are going increasingly to owners of capital, not to labor.”

See chart #3 and Figure 1.

Obamacare, tepid US growth fuel part-time hiring

http://www.cnbc.com/id/100977130

‘Economists and staffing companies are cautiously optimistic that part-time hiring and the low wages environment will fade away as the economy regains momentum, starting in the second half of this year and through 2014.

But businesses, accustomed to functioning with fewer workers, might not be in a hurry to change course. A study by financial analysis firm Sageworks found that profit per employee at privately held companies jumped to more than $18,000 in 2012 from about $14,000 in 2009.

“Private employers are either able to make more money with fewer employees or have been able to make more money without hiring additional employees,” said Sageworks analyst Libby Bierman. “The lesson learned for businesses during the recession was to have lean operations.”‘

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101135835

“Asset bubbles alone don’t cause financial crises like the one in 2008, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan told CNBC on Wednesday. Instead, the combination of bubbles and leverage is the problem, he said.

“We missed the timing badly on September the 15th, 2008 [the day Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy]. All of us knew there was a bubble. But a bubble in and of itself doesn’t give you a crisis,” he said in a “Squawk Box” interview. “It’s turning out to be bubbles with leverage.”

Take the explosion of the dotcom bubble in the 1990s and even the stock market crash of 1987, he continued, they barely showed up in longer-term economic growth figures.

In his new book, “The Map and the Territory,” the 87-year-old Greenspan reflected on the 2008 financial crisis and the questions it raised about the economic models used to predict risk. He looked at the shortcomings of current forecasting tools and how they can be updated to take better account of human nature.

“If you’re looking at the distribution of outcomes, fear is hugely more important than euphoria or greed,” Greenspan told CNBC. “Bubbles go up very slowing and then they go bang.”

After the 2008 crisis, Greenspan said, he came to realize there was “something fundamentally wrong” with the way he and many colleagues were looking at the economy. “I was shocked, surprised, and since delighted at how many of the aspects of fear, euphoria and time preference … [were] systematic,” not random.”

Japan , Abenomics

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101142483

“Many analysts have attributed the recent uptick in inflation data to higher energy import costs, rather than a substantial improvement in consumer spending or corporate investments, which effectively distorts the numbers.

(Read More: Why Japan stocks may storm higher even if the yen firms)

With several of Japan’s key nuclear power stations suspended, the country has to rely on imports to meet its energy needs, which have become more costly given the yen’s near 12 percent decline against the dollar this year.

Schulz, too, attributed the recent rise in inflation to energy costs skewing the data. He also saw the planned consumption tax hike from 5 to 8 percent next April as a potential headwind.

“Right now we have a build-up of additional demand before the consumption tax hike, which will be implemented next spring, after that we will have a drop,” he said.

Other analysts were also reluctant to become too optimistic on Japan’s inflation numbers.

“Even though we’ve seen positive numbers for four consecutive months, it will take a very long time for Japan to meet its 2 percent inflation target,” said Junko Nishioka, chief Japan economist at RBS Securities.

Nishioka said two main factors were at play: the yen appears to have halted its weakening trend, pulling back to 97 to the dollar from 100 in early July; companies are still struggling to transfer input costs to their output prices.

(Watch This: Energy imports root of Japan trade deficit: Pro)

“The pace of [adjusting output prices] is very slow in Japan because most of the price makers have been suffering deflationary costs for a long time. So it’s hard for them to increase output prices despite the more healthy condition of the economy,” she said.

Meanwhile, Paul Donovan, managing director and deputy head of global economics at UBS told CNBC that although Japan’s inflationary level seemed to be picking up, it was the “wrong sort of inflation.”

(Read more: Abenomics speeds corporate investment, but not in Japan)

“You’re seeing food and energy price inflation, wage deflation and consumer durable goods deflation. It’s the worst possible inflation for getting a sustained recovery because it makes the consumer feel really bad,” he said.

“You really need wage inflation and that isn’t coming through at the moment. If people feel their incomes are higher, then they will be prepared to spend money in a meaningful way,” he added.”

Retirement research:

Why 401(k) savers don’t have enough to retire

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101153706

“Many workers say they would like to put more money into their 401(k) plans but simply don’t have enough left after paying everyday expenses to do it.

That’s the new reality. Most Americans with 401(k) and other defined contribution plans are accumulating debt faster than they’re saving for retirement, according to a new report from the financial services website HelloWallet.

The amount that retirement plan participants spent to pay down debts has risen nearly 70 percent in the last 20 years, the study found. Many workers say they are unable to contribute as much as they would like to their 401(k) plan because they have more expenses and less income than they had in the past.

(Read more: Over 50? Ask your financial advisor this)

The problem is most pronounced for those closest to retirement. Half of retirement plan savers 50 to 65 are accruing debt faster than they’re building up their savings, according to the HelloWallet study. They’re spending an average of 22 percent of their income paying down debt.

“It’s remarkable,” says HelloWallet CEO Matt Fellowes. “You’d expect most people at that point to be deleveraging: paying off their mortgage, paying back their student loans or have already paid off their student loans, and not having difficulty paying off credit card debt. But in fact those are the households that are most likely to be building up debt faster than retirement savings.”

The result is that these older workers have only about two years of retirement income saved. Yet Americans are living longer and will typically need about 17 years worth of retirement income after age 65.”

Debt Savers in Defined Contribution (401-k) Plans

http://info.hellowallet.com/rs/hellowallet/images/debtsavers.pdf

Six feet under as a retirement plan?

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101133464

Richard Alford: On Grading the Bernanke Fed

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/11/richard-alford-on-grading-the-bernanke-fed.html

Japanese Households Without Savings Climb to Most Since ’63

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2013/11/japanese-households-with-zero-savings.html

Will debt derail Abenomics?

http://blog.mpettis.com/2013/11/will-debt-derail-abenomics/

Recovery’s Great If You Were Already Rich (or Even Modestly Well Off): Ritholtz Chart

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-11-12/this-recovery-s-great-if-you-were-already-rich.html

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2013/11/no-money-to-retire-new-american.html

“Call it the new American nightmare: Running out of money in retirement is scaring the **** out of record numbers of older workers, forcing them to stay in the workforce.

Now 80 is the new 60 when it comes to retirement. Many older workers who finally clock out have sharply underestimated their financial needs in retirement, raising the specter of personal financial disaster.

By putting off retirement the Baby Boomers are a large reason for the high levels of unemployment for those looking to enter the workforce. According to the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics the rate of joblessness in people 20- to 25-years old is 12.5 percent, twice the rate of people 25 and older.”

And, “The percentage of older middle-class Americans who said their day-to-day financial concern is “paying the monthly bills” has climbed from 52 percent last year to 59 percent today, according to Wells Fargo. Saving for retirement comes in second. Four in 10 say saving and paying the bills is “not possible.”

Older adults are now the fastest-growing share of the US labor force. By 2020, workers 55 and older will comprise a stunning 25 percent of the civilian labor force.”

Personal finance and monthly budgeting matter macroeconomically.

Striking it Richer:

The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States

(Updated with 2012 preliminary estimates)

Emmanuel Saez, UC Berkeley•

September 3, 2013

http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2012.pdf

See page 7 thru page 10. (table and figures)

http://www.cnbc.com/id/101207907