With an national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

The intersection of neoliberalism and fictional mainstream economics is damaging a generation of Japanese workers

The – Japanese asset price bubble – burst in spectacular fashion in late 1991 (early 1992) following five years in which the real estate and share market boomed beyond belief. The boom coincided with a period of over-the-top neoliberal relaxation of banking rules which encouraged wild speculation. The origins of the boom can be traced back to the endaka recession in the mid-1980s, after the signing of the – Plaza Accord – forced the yen to appreciate excessively. This was at the behest of the US, which wanted to reduce its current account deficit through US dollar depreciation. The narratives keep repeating! This post, however, is not about the boom, but its aftermath. The collapse in 1991-92 marked the beginning of what has been termed the – Lost Decades – which was marked by a trend slowdown in economic growth, deflation, and for the purposes of this post, cuts in real wages as nominal wages stagnated. While the long period of wages stagnation was bad enough for Japanese workers, there is still hardship coming as the cohort who entered the labour market during this period reach retirement age. This post is part of work I am doing on Japan, which I hope will come out in a new book early next year after I return from my annual working period in Kyoto towards the end of this year.

In relation to the labour market, the period directly following the bubble crash has been termed the – Employment Ice Age – and the young workers that entered the labour market after finishing school between 1993 and 2003 during this period are referred to as the ‘Ice Age Generation’.

For that decade or so, this generation of workers was locked out of the stable occupational structures and were forced to rely on unstable, poorly paid positions in order to survive.

The companies that survived the crash faced dire economic conditions and were carrying huge numbers of older workers who were essentially in life-time employment.

To survive, these employers effectively froze graduate recruitment and offered new positions in the secondary labour market where they needed extra labour.

In 1993, there were 17.1 million Japanese children and teenagers aged between 10 and 19.

That number was stable going back to 1970 (16.9 million), which are the oldest members of the ‘Ice Age Generation’, where they encountered the end of the bubble soon after graduating from university.

The ‘Ice Age Generation’ thus are now aged somewhere in their 40s and 50s, with some nearing retirement age.

The legacy of this period is that a whole generation of workers have encountered disadvantage which has multiple dimensions.

First, there is the phenomenon of – Jōhatsu – or ‘evaporation’, which describes the situation where people withdraw from society in shame.

I recall being in Tokyo in the mid-1990s for some work meetings and in the early morning I would go out running through parkland not far from the hotel.

The main park in that vicinity was full of tents, cardboard box houses etc and were occupied by so-called – salarymen – of the ‘Ice Generation Age’, who had and/or lost their jobs or were burdened with debt as the asset prices collapsed.

Many of these men still wore business suits as they waited for the charity service each morning to deliver hot rice and tea.

It was a surreal scene and has stuck in my mind ever since.

Nearby, I would also observe men in business suits sitting on park benches all day with their brief cases.

This group were not the Jōhatsu people in the park but workers who had lost their jobs and were unable to admit to their families and as such pretended to be at work.

Many of that group did become the disappearing class.

There is a reluctance in Japan to discuss this trend even though it is “estimated that 100,000 Japanese people disappear annually”.

The related phenomenon is – Hikikomori – or “severe social withdrawal” which affects a growing number of Japanese people.

The Japan Times discussed the so-called ‘8050 problem’ in this analytical article (November 14, 2018) – The ‘8050 problem’ – ‘hikikomori’ people entering 50s as parents on whom they rely enter their 80s.

This problem is closely linked to Hikikomori and:

… refers to “children” in their 50s whose only means of support are parents in their 80s.

The ‘8050’ group:

… is defined loosely as those aged 35 to 44 who left school between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, were unable to get permanent jobs, and ended up flitting from one low-wage, dead-end part-time job to another.

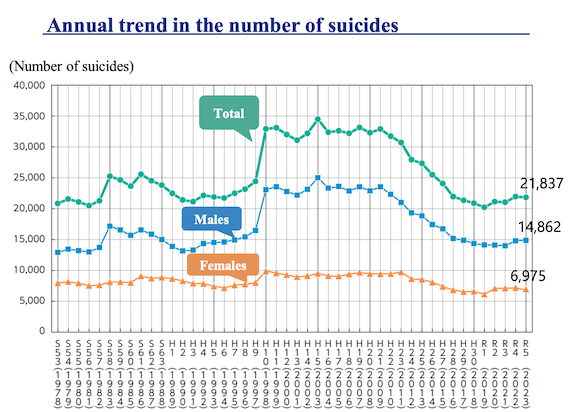

Second, there was a jump in suicides after 1994.

The following graph taken from the – The 2024 White Paper on Suicide Countermeasures – published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare shows the annual suicide numbers from 1978 to 2023.

The dating is first in Japanese – SS is the Showa era from 1926 to 1989 so SS58 corresponds to 1978 in Western dating conventions.

H1 onwards refers to the start of the Heisei era which began on January 8, 1989 and ended on April 30, 2019, to be followed by the Reiwa era from May 1, 2019.

We are now in R7.

The White Paper also noted that:

Suicide mortality rate (the number of suicides per 100,000 population) has increased in different age groups since 2020; In

particular, it had continuously increased until 2023 among those in their 40s and it had greatly gone up through 2021 to 2022

among those in their 50s.

This is the burden borne by the ‘Ice Age Generation’.

Third, this generation has found it more difficult to start and sustain families, which is one of the contributors to the declining population.

But more generally, this generation has endured poor financial and health status, and is approaching retirement age with little or no saving or wealth.

Some have never really been able to find secure employment.

While the ‘Ice Age Generation’ has endured hardships throughout their adult life, their problems are becoming worse as they approach retirement age.

The way the Japanese pension system is constructed makes it certain that many members of this group will live out the rest of their lives in abject poverty.

There are several related issues that relate to this conclusion.

First, the – Japanese Welfare State – is not particularly generous and is described as a “non-typical conservative regime” where it is assumed that much of the old age support will be provided by families.

The data shows that “65% of the elderly live with their children”.

While the government welfare support is increasing in scope and magnitude, it remains that Japan is in the lower end of OECD countries in terms of welfare spending.

However, the problem for the ‘Ice Age Generation’ is profound when it comes to access to the national pension system, which is complex in Japan.

The system has three levels – supported by government and corporations.

1. Basic pension or Kokumin Nenkin (国民年金, 老齢基礎年金) – which provides “minimal benefits”.

To be eligible for the full pension payment, a worker has to contribute currently ¥16,980 per month for 480 months during their working life (40 years x 12 months).

The full basic pension is currently ¥69,308, which is very low, especially when the recipient may not own their own housing.

A pro-rata pension can be paid if the contribution has been for at least 120 months.

The exemptions for the pro-rate payment can be:

(a) Full – upon which the person gets 1/3 to 1/2 of the basic pension (a pittance) depending on when they were exempted and doesn’t have to pay a contribution – this is confined to very low income workers.

(b) 3/4 exemption – monthly contribution of ¥4,250 for a 1/2 to 5/8 pension (depending on when exemption granted).

(c) 1/2 exemption – monthly contribution of ¥8,490 for a 2/3 to 3/4 pension (depending on when exemption granted).

(d) 1/4 exemption – monthly contribution of ¥12,740 for a 5/6 to 7/8 pension (depending on when exemption granted).

2. Top-up or Fuka nenkin (付加年金) pension component – income based as a percentage.

3. Employees’ Pension or Kōsei Nenkin (厚生年金) – company pensions varying in coverage and generosity based on salary and contributions.

So one can see the problem.

Not only is the Basic pension fairly low, but to qualify one has to have worked continuously for a long period.

The design was based on the stable employment that Japan enjoyed prior to the bubble crash.

But for the ‘Ice Age Generation’, the design is totally inadequate, because their work attachments have been at best sketchy and they have not built up the necessary eligibility for the full basic pension or the more generous Kōsei Nenkin.

So not only have they failed to accumulate wealth during their working age, but upon retirement they will be forced to live on the basic pension (at best) or most likely a pro-rata fraction of that pension.

The debate in Japan at present then is about what will happen to this cohort.

It is clear that the Japanese government will have to provide additional welfare support to stop this group from being homeless or malnourished.

But then the mainstream economists step in and claim that the fiscal burden will be too great.

The Liberal Democratic Party, which dominates is full of politicians who refuse to increase the generosity of the system either in the form of higher pension payments or more broadly, provision of state housing etc.

The Japanese government could have also ensured that the employment prospects were improved for this generation through public sector employment.

There is no shortage of work to be done in Japan and the ability of the ‘Ice Age Generation’ to better prepare for their old age would have been enhanced through the provision of more stable public sector jobs.

The Japanese government is aware of that but has not done enough to advance that goal.

Conclusion

It is a further example of how the calamity caused by neoliberalism intersects with fictional mainstream economic thinking to undermine the well-being of the people.

It would be easy for the government to solve the material dimensions of this problem.

Which might also go some way to reducing the psychological burdens this generation bear.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Earth cannot meet additional demands on non-renewable natural resources (materials, energy), even should it be decided to finance the purchase of yet more goods.

One could argue for redistribution of existing goods, rather than the creation of new goods. But that is a different argument than the argument over the ability of the state to finance new goods.

Overall, the issue today is not about whether we can finance new goods. The issue is that the Earth cannot provide more goods, whether we can finance them or not.

Some phenomena observed in Japan are also occurring in Europe and North America. This has become especially noticeable since the Global Financial Crisis, as the austerity regime is creating failed generations.

(Some) People talk about recovery, but I don’t believe it has happened. For a real recovery to occur, the paradigm must change and history shows how much human sacrifice is required for such a shift.

As for Japan, I’m uncertain, but in Europe, I see increasing violence. The european ruling class has already inflicted so much harm on its population and shows no signs of stopping…

More than governments acknowledging reality, it is the majority of people who must recognize the injustices and harm neoliberalism has caused. Governments serve the ruling class, this is obvious in Europe and North America.

Thanks Bill for very insightful blog. Shows that travel when accompanied by keen observation allied to knowledge can broaden the mind. In the UK, over just the last few years, due to the pensioner vote, the state pension has been protected better than much other state spending. Future pensioners when faced by the consequences of the undermining of the economy by the government backed private pensions industry and housing as investment (debt) industry may look back and see this as pretty much the only decent thing governments did for future generations (though undermining their welfare in pretty much every other way).

@John (May 9th)

But governement can of course intervene in markets to reduce (or eliminate) poverty.

Even Trump has apparently issued an executive order forcing drug companies to reduce prices in the US – yikes!

The drug company execs are screaming of course.

Trump wants a cheap supply of viagra

I think many young people entering the labour market in the 90s in NZ were pretty stuffed too. Huge loans, long recessions, neoliberalism red in tooth and claw…wild west labour laws. I certainly remember witnessing the misery and insecurity. Then again I can’t really say i remember “a good economy” ever. I do remember early 80s NZ as being a gentler place where most people seemed to have the basics. No paradise but more secure for working people.

Thanks Bill for this sobering post. I have been reading about the Plaza accord lately as well since it relates, as you note, with the current situation. Overall problem of international monetary system and its adjustment mechanism, ref. Keynes. Looking forward to your book on Japan. Keep up the nice work.

Hi bill if people spend from savings it reduces the deficit while increases transactions and potentially inflation. Government spend and get all back as tax only tax leakage from circular flow more transactions before come back as tax then tax and saving in circular flow. Possibly structural deficits are deflationary!

Hi,

I believe the mainstream theory government finances spending by tax, borrow or print is wrong. In the UK all government spending works by creating money and there are unlimited intraday overdrafts at the central bank borrowing happens at the end of the day. Money can’t leak abroad it is a swap/exchange, not a conversion. If there is no saving or pay back bank loans in the spending chain you will get all government spend back as tax. Similarly, if people spend from savings or take out bank loans and spend no saving or pay back bank loans get all that money back as tax too. Government spend at Tesco get some back as VAT (taxes as ‘cashback’), Tesco pays its employees another chunk taken by government in income tax and so forth.

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmpubacc/349/349ap02.htm

Point 20 says:

“ensure that its position is balanced at the end of each day”

Also at diagram in bottom surplus/shortfall in consolidated fund.

The bubble period of the 1980s in Japan yielded a CAGR of about 20% (if you buy the Nikkei index in 1980 and sell at the peak in 1990), which is roughly the equivalent of the boom seen in the US tech bubble of the 1990s; the key difference being that the US kept chugging along after a brief recession. Also, not just the Plaza accords, the US was making use of tariffs in 1980s as it is now. If you’re interested, there was a good memoir on Japan’s semiconductor industry (『日本半導体物語 』)that came out last year. The author was an engineer and later an executive at Hitachi, which at one time was the leader in the industry by market share. Right around the time of the Plaza accords, by the admission of the CEOs of American tech companies such as Compaq, Japanese chips had overtaken its US competitors in terms of engineering and sophistication, not just pricing. Yet, the price undercutting angle became the obsession of US policy and to promote ‘fair competition’ the US forced Japanese chip companies to break out the costs of its production using accounting methods determined by the US and effectively applied a tariff in instances where the price of the chips was deemed too low. According to the author, the tariffs costs were immediately made up by slashing the the R&D budget.