Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Wages growth in Australia at record lows

Last week was a very busy data release week and so I am still catching up. Last Wednesday (August 12, 2020), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest- Wage Price Index, Australia – (June-quarter 2020). The ABS reported that the June-quarter result was “the lowest annual growth in the 22-year history of the WPI”. Private sector grow was just 0.1 per cent and public sector growth was 0.6 per cent. The overall WPI growth was just 0.2 per cent. With annual inflation in the June-quarter recorded at -0.3 per cent, real wages grew. But the inflation result was distorted the federal government decision to offer free child care in the early period of the pandemic (now rescinded). The reality is better reflected in the core inflation rate (excluding volatile items) of 0.4 per cent. Taking that measure, real wages fell overall in Australia in the June quarter. Further, over the longer period, real wages growth is still running well behind the growth in GDP per hour (productivity), which has allowed profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.

The summary results (seasonally adjusted) for the June-quarter 2020 were:

- The Wage Price Index grew by 0.2 per cent in the June-quarter 2020, and 1.8 per cent over the previous 12 months – slowing.

- The growth for the private sector was 0.1 per cent in the December-quarter and 1.7 per cent over the year – slowing.

- The growth for the public sector was 0.6 per cent in the December-quarter and 2.1 per cent over the year – slowing.

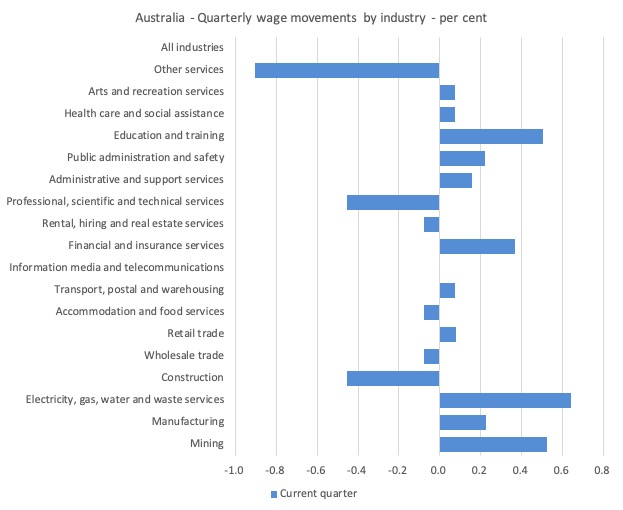

- The largest quarterly wage rises occurred in Electricity, gas, water and waste services (0.6 per cent), Education and training (0.5 per cent) and Financial and Insurance Services (0.4 per cent).

- Wages declined in Other Services (-0.9 per cent), Professional, scientific and technical services (-0.5 per cent), Construction (-0.5 per cent), Wholesale Trade (-0.1 per cent), Accommodation and food services (-0.1 per cent), and Rental, hiring and real estate services (-0.1 per cent).

- The annual CPI inflation rate was -0.3 per cent in the 12 months to June 2020. But as I explain below, the figure is distorted by the administrative decision of the federal government to offer free child care in the early period of the pandemic (now rescinded).

- Labour productivity growth (output per hour) grew by 1.1 per cent over that period.

Nominal wage and real wage trends in Australia

The ABS Media Release – said that:

After a steady period of wage growth over the previous 12 months, wages recorded the lowest annual growth in the 22-year history of the WPI … The June 2020 quarter was the first full period in which COVID-19 social and business restrictions were captured in the WPI …

The June 2020 quarter rise was mainly in the public sector (0.6%). Private sector wage growth eased to 0.1 per cent as businesses adjusted to changes in the Australian economy.

The inflation in the June-quarter was reported at -0.348 per cent, driven by the decision by the Federal government to offer free child care in the early period of the pandemic to ensure the centres remained solvent.

The other inflation measures, which the Reserve Bank of Australia uses when assessing underlying movements, for the June-quarter were:

1. Core inflation excluding volatile items: 0.4 per cent per annum.

2. Weighted median: 1.3 per cent.

3. Trimmed mean: 1.2 per cent.

Which means that irrespective of the inflation measure used, there was a modest real wage increase overall for both public and private employees, which reversed the zero real wages growth in the March quarter (negative for private workers).

The wage series used in this blog post is the quarterly ABS Wage Price Index. The Non-farm GDP per hour is derived from the quarterly National Accounts.

Productivity data available via the RBA Table H2 Labour Costs and Productivity.

The ABS Information Note: Gross Domestic Product Per Hour Worked – says that:

In Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (cat. no. 5206.0) and Australian System of National Accounts (cat. no. 5204.0) the term ‘GDP per hour worked’ (and similar terminology for the industry statistics) is generally used in preference to ‘labour productivity’ because:

– the term is more self-explanatory; and

– the measure does not attribute change in GDP to specific factors of production.

On price inflation measures, please read my blog – Inflation benign in Australia with plenty of scope for fiscal expansion – for more discussion on the various measures of inflation that the RBA uses – CPI, weighted median and the trimmed mean The latter two aim to strip volatility out of the raw CPI series and give a better measure of underlying inflation.

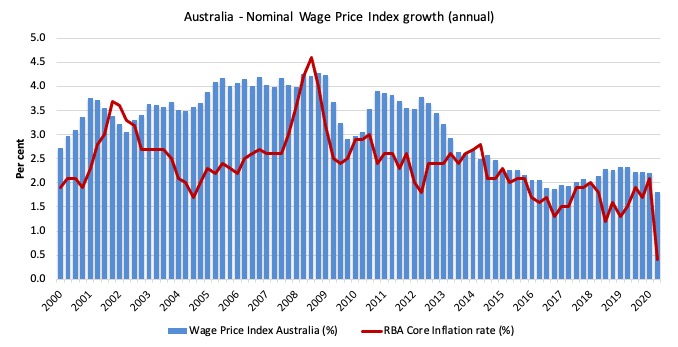

The first graph shows the overall annual growth in the Wage Price Index (public and private) since the December-quarter 2000 (the series was first published in the December-quarter 1997).

I also superimposed the RBA’s core annual inflation rate (red line). The blue bar area above the red line indicate real wages growth and below the opposite.

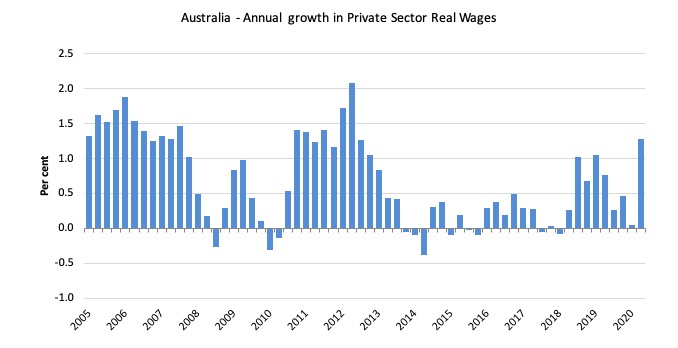

The following graph shows the annual growth in private sector real wages since the June-quarter 2005 to the June-quarter 2020. The Core inflation measure excluding volatile items is used.

The June-quarter result is an outlier – given the temporary government decision to offer free child care (now rescinded).

Throughout 2017 and into 2018, real wages growth was negative. But then there were several quarters of modest real wages growth. The trend, however, is towards zero real wages growth.

The aggregate data shown above hides quite a significant disparity in quarterly wage movements at the sectoral level, which are depicted in the next graph.

6 out of the 18 industrial sectors experienced wage cuts in the June-quarter 2020.

With the temporary negative inflation rate (courtesy of free child care) it doesn’t make sense to produce my usual sectoral real wages graph.

The ABS also reported that:

Private sector businesses reported genuine market-based reductions in jobs paid by individual arrangement to ease financial pressures. These agreements are more sensitive to labour market conditions …

June 2020 quarter WPI reported a higher proportion of wage reductions for Manager and Professional roles than for other occupations.

At an industry level, the Professional, scientific and technical services, Construction and Rental, hiring and real estate services industries had the highest proportions of wage reductions.

In other words, some workers took serious pay cuts – the most affected occupational group – Manager and Professional roles – around 13 per cent.

These cuts were for workers with ‘individual agreements’ while those on enterprise agreements and award based jobs were able to resist the pay cuts.

Workers not sharing in productivity growth

It is one thing for real wages to be rising but that doesn’t mean that the share of worker wages in national income is constant.

Real wages growth means that the rate of growth in nominal wages is outstripping the inflation rate, another relationship that is important is the relative growth of real wages and productivity.

Historically (for periods which data is available), rising productivity growth was shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards.

In effect, productivity growth provides the ‘space’ for nominal wages to growth without promoting cost-push inflationary pressures.

There is also an equity construct that is important – if real wages are keeping pace with productivity growth then the share of wages in national income remains constant.

Further, higher rates of spending driven by the real wages growth then spawned new activity and jobs, which absorbed the workers lost to the productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

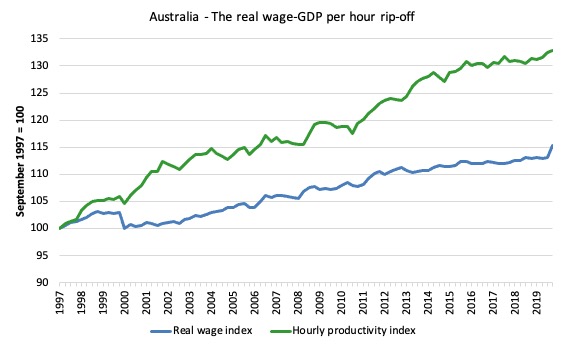

Taking a longer view, the following graph shows the total hourly rates of pay in the private sector in real terms (deflated with the CPI) (blue line) from the inception of the Wage Price Index (December-quarter 1997) and the real GDP per hour worked (from the national accounts) (green line) to the June-quarter 2020.

It doesn’t make much difference which deflator is used to adjust the nominal hourly WPI series. Nor does it matter much if we used the national accounts measure of wages – I will deal with these nuances in a later blog post.

But, over the time shown, the real hourly wage index has grown by 15.3 per cent (although the most recent quarter is distorted by the free child care decision that temporarily reduced the inflation rate for the June-quarter), while the hourly productivity index has grown by 32.8 per cent.

If I started the index in the early 1980s, when the gap between the two really started to open up, the gap would be much greater. Data discontinuities however prevent a concise graph of this type being provided at this stage.

For more analysis of why the gap represents a shift in national income shares and why it matters, please read the blog post – Australia – stagnant wages growth continues (August 17, 2016).

So even though we should be happy to see real wages growth occurring, this does nothing much to redress the massive loss of income that workers might have otherwise enjoyed had real wages kept pace with productivity growth over the stretch.

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go?

Answer: Mostly to profits.

One might then claim that investment will be stimulated.

At the onset of the GFC (June-quarter 2008), the peak Investment ratio (percentage of private investment in productive capital to GDP) was 23.3 per cent.

It peaked at 24.3 per cent in the June-quarter 2013. But in recent quarters it has steadily fallen and in the March-quarter 2020 (most recent data) it stood at 17.6 per cent.

Some of the redistributed national income has gone into paying the massive and obscene executive salaries that we occasionally get wind of.

Some will be retained by firms and invested in financial markets fuelling the speculative bubbles around the world.

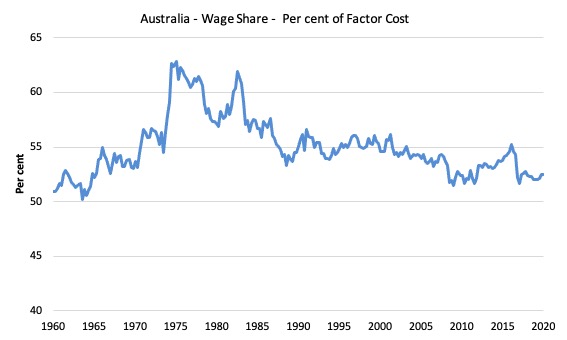

Now, if you think the analysis is skewed because I used GDP per hour worked (a very clean measure from the national accounts), which is not exactly the same measure as labour productivity, then consider the next graph.

It shows the movements in the wage share in GDP (at factor cost) since the March-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 2020.

The only way that the wage share can fall like this, systematically, over time, is if there has been a redistribution of national income away from labour.

I considered these questions in a more detailed way in this blog post series:

1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 1 (November 20, 2019).

2. 1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 2 (November 21, 2019).

And the only way that can occur is if the growth in real wages is lower than the growth in labour productivity.

That has clearly been the case since the late 1980s. In the March-quarter 1991, the wage share was 56.6 per cent and the profit share was 22.2 per cent.

By the March-quarter 2020, the wage share had fallen to 52.5 per cent and the profit share risen to 29 per cent.

The relationship between real wages and productivity growth also has bearing on the balance sheets of households.

One of the salient features of the neo-liberal era has been the on-going redistribution of national income to profits away from wages. This feature is present in many nations.

The suppression of real wages growth has been a deliberate strategy of business firms, exploiting the entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment over the last two or three decades.

The aspirations of capital have been aided and abetted by a sequence of ‘pro-business’ governments who have introduced harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce the trade unions’ ability to achieve wage gains for their members. The casualisation of the labour market has also contributed to the suppression.

The so-called ‘free trade’ agreements have also contributed to this trend.

I consider the implications of that dynamic in this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009).

As you will see, I argue that without fundamental change in the way governments approach wage determination, the world economies will remain prone to crises.

In summary, the substantial redistribution of national income towards capital over the last 30 years has undermined the capacity of households to maintain consumption growth without recourse to debt.

One of the reasons that household debt levels are now at record levels is that real wages have lagged behind productivity growth and households have resorted to increased credit to maintain their consumption levels, a trend exacerbated by the financial deregulation and lax oversight of the financial sector.

Real wages growth and employment

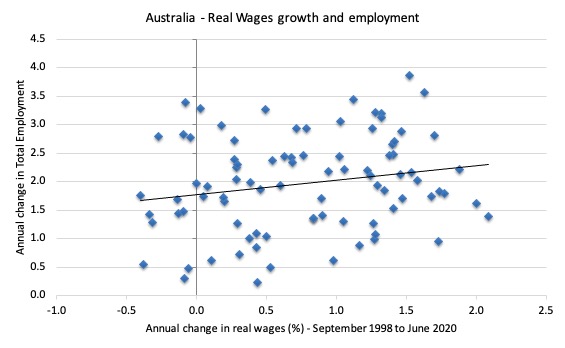

The standard mainstream argument is that unemployment is a result of excessive real wages and moderating real wages should drive stronger employment growth.

As Keynes and many others have shown – wages have two aspects:

First, they add to unit costs, although by how much is moot, given that there is strong evidence that higher wages motivate higher productivity, which offsets the impact of the wage rises on unit costs.

Second, they add to income and consumption expenditure is directly related to the income that workers receive.

So it is not obvious that higher real wages undermine total spending in the economy. Employment growth is a direct function of spending and cutting real wages will only increase employment if you can argue (and show) that it increases spending and reduces the desire to save.

There is no evidence to suggest that would be the case.

The following graph shows the annual growth in real wages (horizontal axis) and the quarterly change in total employment (vertical axis). The period is from the December-quarter 1998 to the June-quarter 2020. The solid line is a simple linear regression.

Conclusion: When real wages grow faster so does employment although from a two-dimensional graph causality is impossible to determine.

However, there is strong evidence that both employment growth and real wages growth respond positively to total spending growth and increasing economic activity. That evidence supports the positive relationship between real wages growth and employment growth.

Noting that we should not draw causality from two-dimensional cross plots.

Conclusion

Australia recorded its lowest rate of wages growth on record (in terms of the Wage Price Index – available since the September-quarter 1997) in the June-quarter.

While the nominal wage increase of 0.2 per cent meant that real wages improved in the June-quarter, that was only because of the negative inflation rate arising from the federal government decision to offer free child care in the early period of the pandemic (now rescinded).

The reality is better reflected in the core inflation rate (excluding volatile items) of 0.4 per cent.

Taking that measure, real wages fell overall in Australia in the June quarter.

Further, over the longer period, real wages growth is still running well behind the growth in GDP per hour (productivity), which has allowed profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.

6 out of the 18 industrial sectors experienced wage cuts in the June-quarter 2020.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Taking that measure, real wages fell overall in Australia in the June quarter. Further, over the longer period, real wages growth is still running well behind the growth in GDP per hour (productivity), which has allowed profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.”

Unless consumers spend their money within the public sector does everything not end up as profits anyway ? Even then the government will still buy from the private sector to improve the public sector which will end up as profits.

With everything ending up as profits, even savings eventually and apart from taxes which destroy broad money. Isn’t the problem the accumulation of those profits ending up in fewer hands ?

Which the virus has amplified, as the online companies like Amazon have absorbed a lot of consumer spending along with a few others like a sponge. Which maybe gives everyone a glimpse of what the future will look like as technology increases and spending habits change. Haven’t we already seen How this plays out over the last decade or so ?

How do you stop profits ending up in fewer hands. Especially when less competition is now a major part of foreign policy ? As governments continue to back their Elon Musk’s and Bezo’s and export industries to the hilt to steal ever more world aggregate demand.

Foreign policy will continue to encourage less taxes and more offshoring of profits than ever before until both China and Russia are defeated. Doesn’t matter what colour is in charge they all sing from the same song sheet.

What makes up the remaining part of national income? If the wages share is 52.5 percent and the profits share is 29 percent, there must be 18.5 percent that consists of other things.

“With everything ending up as profits”

Remember: Profits are spent and interest is spent. And that goes back into the circulation.

The horizontal circuit is a stable flow with a three way diverter in a firm which divides the flow between the wages of workers, the wages of bankers and the wages of capitalists.

It’s about the flow, not the stock. The savings stocks tend to be largely dynamically stable – with almost as much flowing out of them in aggregate as is flowing in.

MMT tends to favour maintaining the flow, and not worrying too much about the stock.

“apart from taxes which destroy broad money”

Net Loan capital repayments destroys broad money too. Loan repayments (including paying for items bought on credit) destroys horizontal money. Taxes destroy vertical money.

Broad and narrow are essentially monetarist terms and of little use as you know. We save narrow money deposits and stuff their calculations up 🙂

To put it another way, the problem is excess savings.

The traditional Left wants to confiscate savings and play Robin Hood handing them out to the “deserving” (based on their current definition of deserving.

The right want to hide the excess savings with ever increasing private credit pushed by a rapacious banking sector.

And MMT says the savings act largely like taxes and are essentially inert so just replace the missing income flow via a Job Guarantee.

Accommodate rather than confiscate or obfuscate

I think that graph of wages vs employment growth doesn’t really show much at all, except to debunk a strong relationship either positive or negative. A simple illustration of this is the error in the prediction is ~2 percentage points above/below regression line. This is larger than the range of predictions themselves, which is about 0.5 percentage points, from ~1.75% growth up to ~2.25% growth.

As usual the macroeconomic story is very hard to talk about “marginal effect” in a meaningful way. Why? because the underlying assumption is that you change one “input” and keep other “inputs” constant. This is often not possible, because the “inputs” are all related to each other. You change one you change the other.

I think you get a much stronger (negative) relationship between wage growth and the underemployment rate or underutilisation rate. And this makes more sense too – if an employer has alternative options, why pay the employee more money? Of course this is likely a nominal wage story rate than a real wage story.

just to follow up on the last point of my post, we have had record high underemployment (and underutilisation) in the same quarter as the record low wage growth. Also, underemployment has been above 8% for the last 7 or 8 years, and wage growth has been consistently below 2.5 percent per annum for this time as well.

True Neil.

But as the virus and pre virus has shown profits are going into fewer and fewer hands. As explained in ” savings are an export product ” you can accommodate but how do you share the profits more widely ?

When trends over the last decade show this has not been happening. The JG can help in many ways but the flow will end up in the same stocks with the same old names written on it as technology moved them to the same platforms.

More competition and more taxes ?

Foreign policy will ensure that won’t happen when you have a competition authority who prefers mergers no matter what colour is in power. They are all the same neoliberal globalists. They prefer to give these guys more power on a global playing field rather than stripping it away.

According to Neil, “MMT says the savings act largely like taxes and are essentially inert so just replace the missing income flow via a Job Guarantee. Accommodate rather than confiscate or obfuscate.” But meta-economic values, held by many in the MMT community, also indicate that the rich, by virtue of their riches, are able to unduly influence public policy to prioritize the preservation and enhancement of those riches over meeting pressing social and environmental needs. Without some degree of confiscation, how is this crucial meta-economic issue to be addressed? Even the exclusive public financing of campaigns, of questionable constitutionality in the U.S. as a potential denial of the right of free (political) speech, would not eliminate the “revolving door” influence of the rich, who would still be able to tempt politicians to promote the interests of the rich in exchange for lucrative private positions to be bestowed upon them after leaving office. Nor would term limits seem to be effective in solving this undue influence problem, because the same corruptive dynamics would be in play regardless of the lengths of the terms of public offices. Thus, I find it difficult–indeed, impossible–to escape the conclusion reached by many others that near-polar wealth distribution is fundamentally incompatible with functional democracy.

” rich, by virtue of their riches, are able to unduly influence public policy”

Not by their riches. By virtue of their little black book they have acquired on the way to being rich. And that doesn’t go away if you remove the money. They still know everybody in power.

The myth amongst many, put out to justify their envy, is that because you gain power by gaining money, you must remove power by removing money. That doesn’t get rid of the little black book. All it does is poke the hornet’s nest.

It’s as fundamental a system error as neoliberals believing they can control an economy with one interest rate.

And means they will never get power because they don’t understand it. They just spend forever talking about who they will tax when the magic sky fairy grants them the power to do so.

Politics involves cutting deals with people you’d rather not. It’s not a game for purists.

Yes Newton. But MMT shows that taxing the financial savings of the too wealthy is an entirely separate issue and is not needed in order to ‘finance’ the government spending on that which we decide is important. We don’t need ‘their money’ to have our government spend on what we want it to. Too often that is not understood and ‘where is the government going to get the money’ becomes the question instead. Separate issue.

Addressing economic inequality is important in its own right and can and should be done for the reasons you laid out. But don’t let it become thought of as a limiting factor in the government spending process- some of which actually addresses that inequality.to begin with.

Neil Wilson: interesting comment, but do you really believe, say, that Conrad Black has the same influence as he had when he was much wealthier and owned all those publications. I do not deny that having, say, been to Eton, helps a lot, but I don’t think that the “bonding” social capital of the wealthy, like the bonding social capital of the mafia, is anywhere as important as current financial and military assets — Stalin’s quote about how many divisions the pope has. There may be longterm effects to that black book, but I think one can overstate its short- or medium-term importance.

I don’t think Richard Branson has the same influence as when Blair was in charge, and he’s still thoroughly minted.

The black book network moves too, and age still withers. The obsession with finance on the left is little more than a mask for deep envy.

“The obsession with finance on the left is little more than a mask for deep envy.”

Envy is what drives capitalism and why socialism fails.

“And means they will never get power because they don’t understand it. ”

Why does the government have power, putting aside legal sanction? It has power because it can create money and is prepared to use that power. Similarly with the wealthy. They have money (and do have networks) but they have to have the balls to use it, and many do. Money confers also a mystique. To argue that there is no correlation between money and power is silly.

@Neil Wilson,

I told you that I don’t envy the super rich. Their children and grandchildren will suffer for their arrogance.

I rewrote this comment because I decided that your sentence only accused “many” of having envy of the rich. Maybe you didn’t intend to include me specifically in that blanket generalization.

Your words seem to ignore the belief that it is money that gives them the power they have.

It is extremely silly for me to worry about the “long run”, when I strongly believe The Club of Rome’s prediction that civilization will (or may) come to an end in about 2050 +/- 20 years. Yet, I think that you are *not* looking at the long run effects that will come from some people 2 to 4 generations then having $10T to spend to undermine the ability of the nation to have “government of the people, by the people and for the people”. It shall have perished form the earth.

This excess wealth does them *zero* good. It will do their grandchildren even less good in a world of reduced living standards due to resource depletion and other limits to excess abuse to the environment. Yet you defend their right to have and keep it. And you don’t see any justice in punishing them for abusing their power to rewrite the economic rules to let them *crush* people as they earned more money & power. Yes, I think that the unemployed (EU) in America are being *crushed* by the super rich who have justified in their minds that the UE deserve what they are getting because they are lazy or something.

So, like most people, your mind is made up and refuses to be ‘confused’ by the facts. In this you are no better than the basic Trump supporter. [Here ‘confused’ relates to my childhood, when my family said this about my Mom who “refused to be confused by the facts.”]

And another thing, Neil, you wrote, “All it does is poke the hornet’s nest.”

So, you are making an analogy and comparing the rich to hornets.

Your analogy fails because hornets are evolved to seem to be smarter than the rich.

Hornets are not smart, but their inborn behavior makes them seem smart.

That is, they have live and let live arrangement with all around them. They do not attack every animal that comes within 100 miles of their nest.

OTOH, the rich do use their power to attack every person in the bottom 70% of earners in the population.

You seem to think that the rich do not know that someday soon (if they let progressives gain political power) the Gov. will begin to tax them more. That they will not know that some progressives will want to increase their taxes, if you can get all progressives to STOP SAYING THAT.

I’ve got news for you. The rich already believe that and we don’t need to tell them that. They know.

Your compulsion to make a big deal out of this is *useless* and makes me at least very mad at you. It seems I’m not the only one either. So, I suggest that you “just stop it”. Just as you suggest “we stop it”. There are more of us in our ‘we’, than the 1 of you in your ‘me’.

Steve, that was quite the rant. I don’t think what Neil wrote was intended as a defense of the ‘rights’ of the wealthy. The hornet thing is an analogy. It is like saying we can’t fix the front steps until we get rid of the hornet nest that is way deep in the back yard. Well we can fix the front steps regardless. And it might be easier to fix the front steps if we leave the stupid hornets alone until after we do that.

Like I said somewhere, I think a solemn promise to definitely *not* on the rest of the top 30% of earners who are not in the top 1% is a better plan. Almost all of the top 1% are going to oppose Progressivism no matter what. Progressives don’t *need* to raise taxes on the rest of the top 30%, so they should promise not to do that, and in this way maybe get most of the top 30% to join them. Their wealth is not excessive, and we don’t need tax revenues to spend. OTOH, the top 1% does have excessive wealth and they often use it to deny the American people gov. of the people, by the people, and FOR THE PEOPLE.

“Progressives don’t *need* to raise taxes on the rest of the top 30%”

But they do need to raise taxes on the bottom 30% to “fund” their UBI and Robin Hood beliefs in real terms.

Do you think the ones with the money don’t know that and aren’t going to point it out? And since you are so obsessed with the super wealthy and taking it off them, they may as well then spend that vast hoard stopping you.

How much PR and propaganda can it buy?

The actual strategy is to point out to the very wealthy that the hoards will eventually overhaul them unless they sort out the bottom end. And that requires more than just throwing a few coins over the wall. It requires a redistribution of jobs and society back to the flyover states.

Look after the unemployment and the black holes of gravity theory will dissipate themselves.

I wrote,

“Progressives don’t *need* to raise taxes on the rest of the top 30%”

Neil Wilson wrote in reply,

“But they do need to raise taxes on the bottom 30% to “fund” their UBI and Robin Hood beliefs in real terms.

This is just wrong. We are not UBIers here. We here are MMTers. That means we intend to spend using so-called deficit spending. We don’t need to raise anyone’s taxes. And we don’t want a UBI.

The last words I quoted just above are “in real terms”. This may mean Neil thinks that deficit spending will cause inflation that will eat into the wages that the workers (= Neil’s the bottom 30%?) will be getting. MMT asserts that this will not happen. Besides which, it is changing the goal posts in the middle of a post. I was talking about raising taxes, he turns it around to talk about inflation as a tax. [If this is what he means, which actually isn’t at all clear.]

I think that this post shows us just how much Neil Wilson doesn’t grok MMT.

“That means we intend to spend using so-called deficit spending. We don’t need to raise anyone’s taxes.”

To do *anything* other than hire the unemployed you need to release the resources from the private sector to do it.

To put solar panels on roofs you need roofers. Not really feasible to use the disabled and unemployed people with no head for heights for that. Only so many people have the skills and aptitude to do the job. It is a scarce resource. Those roofers are currently gainfully employed elsewhere putting roofs on houses.

To redirect them to solar panels you have to stop them putting roofs on houses – which requires taxing with sufficient accuracy to stop people who hire roofers from hiring as many roofers. (Or hiring as many trainers of roofers if you want to go meta).

Otherwise you either end up in a bidding war for roofers – which drives inflation. Or you don’t get any roofers, the grand plans gather dust on the shelf *and no money is injected into the economy*.

This idea that you can go around spending money willy-nilly is precisely the problem with the current progressive narrative.

Once the Job Guarantee is in place and those people are doing jobs they can do (so we are at full employment), everything else is essentially tax and spend.

That is the lesson from MMT.

Neil Wilson.

Trying to create a simple tax on construction that would release enough people to put a lot of solar panels on roofs would not be easy. However, this is just an example, and not that good of one.

The answer is like you said to hire some who are unemployed and train them. Not many trainers would be needed so the inflation impact is small.

In the general case, (I’m no expert but) taxes to free up specific people is as blunt, indirect a tool as using interest rates to fine tune economic growth.

I saw a video yesterday about a “rule” discovered in the 1800s. It says that making a tool more efficient (like burning coal to fire steam engines) does NOT cause a reduction in coal usage. It increases it.because more efficient steam engines can have more applications.

Taxing something may just cause businesses to avoid the tax. That seems to happen a lot now.

I have not seen any core MMTer saying that they intend to raise taxes on the economy to free up **specific** resources. MMTers seem to talk in generalities on this subject.

In WWII the US didn’t tax tires, it rationed them. The UK didn’t tax meat, it rationed meat. I think that i the crisis doesn’t allows us time to train workers then taxing the economy will not free up the needed workers fast enough anyway. Better to just draft them in that crisis.

And if may ask, what the heck did you mean by “taxing the bottom 30% … in real terms”? What good will taxing the bottom 30% do? They don’t have the money, the super rich do. I don’t grok your point.

@ Neil Wilson

It strikes me that you may be becoming too preoccupied with the support which some (many?) self-defined progressives give to a UBI and Robin Hood taxes.

It may be irritatingly misguided but is it really as important as the prominence you give to attacking it suggests you think it is? I don’t know, but I do wonder.

Also, could you perhaps condescend to explain what you mean by the rich’s “black book”. It’s not a self-explanatory expression. Why are we expected to guess?

“I have not seen any core MMTer saying that they intend to raise taxes on the economy to free up **specific** resources.”

Macroeconomics, pp323

“We’ll just train people” and “we’ll tax generally” is an appeal to fungibility – the idea that people are just interchangeable units that can be swapped in and out if you throw enough training at them.

They are not. Wages are only higher than the living wage because, amongst other things, skills are scarce. It’s not just that it is rather more difficult to increase skills in aggregate than some people seem to believe, but that those with the skills won’t want them replicating – since that may drive down wages. There is a guild effect to overcome.

Training is rather more intrusive than you may imagine. It reduces your current capacity to produce output. It’s one of the reasons apprenticeships and youth training gets jettisoned. Spending the seed corn is always easier in the short run.

Reduced output is inflationary and has to be offset. Taxing entities that refuse to train would be one attempt at fixing that.

Taxation is a lousy tool because it has a tendency to be imprecise. It’s more like carpet bombing an area than a surgical strike. More targeted taxation gives greater room for manoeuvre since you can guarantee the correct resources are freed up for use and you’re not going to get into either a bidding war, or end up with an ineffective intervention due to lack of manpower.

” I think that this post shows us just how much Neil Wilson doesn’t grok MMT”

Seriously???

He could eat you, and everyone else here with the exception of Bill, for MMT breakfast!

MrShigemitsu

[q]” I think that this post shows us just how much Neil Wilson doesn’t grok MMT”

Seriously???

He could eat you, and everyone else here with the exception of Bill, for MMT breakfast![/q]

So I’ve been told.

He doesn’t seem like that in his posts.

Like where he talked about taxing “the bottom 30% … in real terms.”

I’m not sure what he meant, so I asked him, and he relied, but didn’t explain that part.

However, this seems to attack the core MMTers for not getting the unintended consequences of what they propose.

He also fails to communicate to those who don’t have degree in econ, like me.

.

Steve, Neil Wilson has helped me learn about MMT. I’m sure he understands it very well. I think he should be commended for attempting to help others learn. He is under no obligation to do so and he has been doing it for a long time.

I don’t have a degree in econ either – which I see as an advantage, frankly – but I manage to keep up.

Neil introduced me to MMT years ago via his indefatigable posts in the Guardian, for which I am extremely grateful.

But he doesn’t suffer fools, and neither does he spend time hand-holding with entry-level issues any more. Although he sometimes cannot resist a provocative tease, he makes you work harder, so you have to think on your feet and engage some mental agility to interpret his often playfully and deliberately opaque references and metaphors.

The challenge is all the more rewarding and exquisite when the penny finally drops.

I’m glad to see him back on billyblog after his hiatus.