Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Fundamental lack of leadership vision in Australia’s response to the pandemic

Today, the Prime Minister of Australia indicated that the ‘effective’ unemployment rate in Australia is heading to 13 per cent as a result of the harsh lockdowns that have just begun in Victoria as it reels under a second wave of coronavirus (Source). The effective rate incorporates the official estimate (based on activity tests – search and willingness), the number of workers who have dropped out of the labour force due to a lack of opportunities, and those on wage subsidies who are not working at all. The Stage 4 Melbourne lockdown for the next six weeks will cut GDP by a further 2.5 per cent. While economists fuss about microeconomic losses, the daily output and income losses from the unemployment and underemployment are massive, not to mention the huge personal, family and community losses. A responsible government, which issues its own currency and can procure any productive resources that are idle, would be doing everything it could to ensure these losses do not occur. It is not rocket science. The Federal government could ensure those who are unable to work due to the lockdown maintain their current incomes. The overwhelming impression I am getting as we enter the fourth month of this crisis is that the federal polity in Australia is lost. The scale of the disaster has so confronted the neoliberal DNA of the major parties that they are failing to articulate a coherent and viable short- and medium-term plan to deal with the crisis. The challenge is for the government to abandon its inclination to see a ‘return to surplus’ as a benchmark it aspires to. That mentality is making this disaster a catastrophe. We can do much better.

The prelude

It is also clear that Australia was ill-prepared for a crisis of this dimension and that the way in which we have adjusted to the crisis has ensured it has been worse than it might have been.

What does that mean?

There is evidence from the current Victorian difficulty in dealing with the second wave that many workers are still evading the restrictions because they do not have the economic means to ‘stay at home’, in the same way a higher income worker in professional occupations have.

Prior to the crisis, the Federal government (in various periods) has clearly encouraged and abetted the flattening of wages growth, the cutting of penalty rates for low income workers in service sectors, the profiteering of banks via excessive user charges and lax credit behaviour, the increased casualisation of the workforce, and the rise of the gig economy.

And its obsession with achieving a fiscal surplus, saw the Australian economic growth decline to around half its previous trend rate, and labour underutilisation rise to around 13.5 per cent as we headed into the pandemic.

So already, the economy was wasting at least 13.5 per cent of its available and willing labour supply because the government refused to spend enough to support output and income growth.

The obsession with surpluses has also caused degradation across our society in key areas:

1. Education – particularly vocational and higher education – the quality is declining, research funding is being squeezed, and there has been a bias pushed towards private, commercially-exploitable STEM outcomes rather than basic research across all areas of human society.

2. Public infrastructure – development handed over the private, profit-seeking developers under Public-Private Partnership agreements, which have reduced the quality of services arising from such capacity. Cutbacks to fire services etc ensured the bushfire disaster that preceded the pandemic caused more destruction than was necessary.

3. Telecommunications – the NBN disaster is directly the result of trying to make the agency responsible cover ‘costs’ via user pays and then scale down the quality of the technological innovations to ‘save’ federal outlays.

4. Utilities – for example, water and electricity supply. Excessive charges, declining quality of service and environmental disasters.

5. Public housing – Australia faces a shortage of 400,000 low-income houses as a result of refusing to invest.

6. Training and skills development – the obsession with creating a ‘competitive’ private training market has been a disaster.

7. The ‘unemployment industry’ – the privatisation of the public Commonwealth Employment Service and handing over the tasks to profit-seeking private operators has just created ‘rents’ for these operators, who rort the system and deliver no productive outcomes for the unemployed or society in general.

8. The climate crisis – neither political party will commit to carbon targets that will address the climate crisis in any effective way.

9. Household debt is at record levels and has maintained consumption expenditure growth in the face of flat wages growth. It is now so high that consumers are cutting spending in order to reduce the risk of insolvency.

On February 9, 2017, our Prime Minister who was then Treasurer demonstrated his concept of leadership when he brought a lump of coal into the national parliament as a statement of support for the fossil fuel industry and a indication that he rejected any climate change narratives.

That is the standard of leadership we are dealing with.

All these points taken together mean that we entered this crisis in a fragile state.

They also give a clue as to how a fiscal package might be best designed to deal with the economic damage of the crisis and position the nation in better shape in the future if we can get beyond the health issues.

The stark reality is that the Federal government’s response so far has not reflected any recognition of these structural weaknesses that their own past policies have helped create.

Effective leadership will require a fundamental shift in the past policy approach – away from the obsession with surpluses towards a major new period of nation building of the sort we saw in the immediate post WW2 period as the government took responsibility for putting the nation on the path to prosperity.

That sort of leadership was exemplified by the – 1945 White Paper on Full Employment.

Both major political parties have so far failed to articulate such a leadership plan.

Stop recession at all costs

In this blog post – Governments should do everything possible to avoid recessions – yet they don’t (June 29, 2020) – I made the case for governments taking a highly risk averse approach to dealing with crises.

It is better to err on the side of ‘too much’ net government spending, given the inflation risk is biased downwards, than to worry about the rising fiscal deficits.

Remember that government should never target a particular fiscal outcome.

How it should assess its performance is not in terms of any particular number is posted each year about the fiscal balance.

There is nothing you can say about a 10 per cent of GDP fiscal deficit relative to a 2 per cent deficit or a 1 per cent surplus, other than, the 10 per cent is a larger public contribution to GDP than a 1 per cent surplus.

But nothing qualitative can be said about that.

Which fiscal position is the appropriate one?

The answer is that is always depends on the context.

Australia runs a consistent external deficit, which means overall private domestic saving requires government deficits to support growth.

The only question now is how large the support from fiscal deficits should be.

Private debt levels have to fall and employment has to be supported.

My estimate is that the government might be at least $A100 billion short of where it should be.

The point is that capitalism is now on state life support. The only game in town that will maintain that fiscal policy.

The Government’s response has been inadequate

While the Federal government has provided a substantial fiscal stimulus of around $A164 billion (around 8.6 per cent of GDP) through to the financial year 2023-24 (Source).

The JobKeeper wage subsidy amounts to 4.5 per cent of GDP.

Other measures include loans to businesses, a HomeBuilder program to support the construction sector (but biased towards private, higher-income home building), some fast-tracked infrastructure projects, some modest support to the arts sector, free childcare for a time (see below), some skills investment (JobTrainer) and a temporary increase in the unemployment benefit (JobSeeker).

The State and Territory government stimulus packages on top of that federal support amounted to around 1.7 per cent of GDP.

Is that enough?

Clearly, if the effective unemployment rate is now 13 per cent (as above) then the conclusion that the fiscal intervention is way short of where it should be.

Part of the lack of leadership is in the on-going uncertainty that is crippling the confidence of consumers and firms.

The government was so unwilling to abandon its obsession with surpluses that is fiscal responses all had relatively short sunset clauses built into them. The JobKeeper program was initially for 6 months only.

It also was mean-spirited in the sense that it excluded more than 1 million casual workers – who were not in a position to manage the loss of income they faced with the lockdowns.

It also excluded the university sector, which has 70 per cent of its staff as casual workers. Many of these casual workers are also postgraduate students pursuing research careers and the evidence is mounting that they are abandoning their studies because they can no longer cope with the lack of income.

The size and scope of the schemes aside, the lack of willingness to provide certainty about the continuation of these schemes plagued the public debate in the months following the pandemic.

Everyday, there were pleas expressed in the media from businesses etc for the Government to provide more certainty about extending these programs.

The Government lagged those concerns. And when it finally agreed to extend the schemes for some time as the crisis became deeper, they also announced they were scaling the fiscal support back in a number of ways.

The abandoned free child care. They will cut the unemployment benefit supplement and the JobKeeper wage subsidy.

That is their version of leadership – cut fiscal support as the scale of the pandemic disaster intensifies and the socio-economic costs increase!

And the other dimension of this is that they are being dragged along by the disaster rather than showing a confident and well articulated path out of it.

They announce x dollars support, driven by their overall bias towards not expanding the deficit. Then the socio-economic crisis gets worse, in part, because the government has penny-pinched.

This creates incentives for exposed workers to avoid the health restrictions and the second wave of the pandemic intensifies.

Then the government responds – not leads – but cannot get beyond its neoliberal DNA.

This is where we are at.

The Opposition Labor position is no better.

They harangue the Government about jobs and other matters but they also have no clear path to follow.

They will not commit to major public sector job creation.

They will not commit to a Job Guarantee.

They will not commit to fast tracking green technologies and closing coal down.

They will not commit to major funding to education.

And so it goes.

What should it be doing?

The former Federal secretary was in the media yesterday extolling the virtues of productivity growth as the way to meet the challenges posed by the pandemic.

I agree that future material prosperity in an ageing population requires productivity growth to accelerate.

But I disagree that we need more deregulation (to stop “gumming up the system”) and more corporate tax cuts to achieve that.

The former Treasury secretary told the media that we need “to drive investment faster”, cut taxes and improve the skills of the workforce.

Basically more of the neoliberal agenda that has ruled since the 1980s.

Question: Has this agenda delivered faster productivity growth?

Answer: Definitely not.

Question: Has it delivered higher investment growth rates?

Answer: Definitely not.

Consider the following table which shows the decade average results for annual GDP growth, Labour Productivity growth per persons, and per hour worked, and private capital formation.

The 1960s were a superior decade relative to what followed.

Ask yourself why?

| Decade | Average annual GDP growth | Average LP persons growth | Average LP hour growth | Private Investment |

| 1960s | 4.9 | 2.3 | n/a | 6.2 |

| 1970s | 3.3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| 1980s | 3.4 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 6.6 |

| 1990s | 3.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 4.0 |

| 2000s | 3.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 5.6 |

| 2010s | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.23 |

| March 2020 | 1.4 | -0.81 | 1.4 | -3.6 |

The 1960s was the last decade of true full employment (unemployment below 2 per cent, no underemployment, no hidden unemployment) with high participation rates (for men), no youth unemployment, strong investment in public infrastructure, including state-owned utilities, strong investment in all levels of education, expanding public health, strong real wages growth, a widespread public sector apprenticeship system combined with occupational planning, and more.

Fiscal policy was most always in deficit supporting a household saving ratio up around 16 per cent of disposable income through the strong real GDP growth.

Household debt was low.

Housing affordability was high.

This was a nation building decade.

As the neoliberal deregulation agenda unfolded, all in the name of productivity growth, real wages started to lag badly behind productivity growth and national income was redistributed to profits as a result (a wage share in the high 59 per cent about to the lowest share now in history around 51 per cent).

The redistributed national income – achieved through deregulation of the wages system and other industrial relations legislation that weakened the position of unions – went to profits but not to capital formation.

It formed the basis of excessive executive salary increases (obscene is the word) and speculation in financial markets as the government deregulation went further.

Elevated levels of labour underutilisation became the norm as growth rates fell on average and labour productivity slumped.

Public investment was also cut and major shortages of social housing emerged.

The utilities were largely sold off to private buyers and service slumped and prices rose.

No wonder productivity growth was inferior.

Which should disabuse you of the idea that more of the same will provide the solution.

Productivity growth requires the government invest strongly in new public infrastructure to allow the private firms to leverage their own productive capacity growth.

We need cheaper power by nationalising the privatised utilities.

We need cheaper health care by eliminating the private insurance companies that can only survive because government allows them to hike charges in excess of CPI growth.

We need to stop cutting the training and higher education capacity – and stop pumping billions into fly-by-night private training providers.

In that vein the government might increase its current stimulus by:

1. Expanding public employment and improving service delivery across the range of government departments by offering well-paid, career positions.

2. Renew investment in large-scale public infrastructure to improve transport systems, bike transport capacity (which will become more important as we deal with the pandemic and beyond).

3. Nationalise water and power to stop the price gouging and lack of private investment.

4. Announce a major social housing construction phase and require all contractors to employ apprentice tradespersons as part of the deal. We need about 400,000 new homes, which will take some years to complete and will provide thousands of job opportunities for young people desiring to learn a trade.

5. Abandon plans to make the NBN pay for itself via excessive pricing. Make the broadband free and ensure it is fibre throughout rather than the cost-cutting hybrid of technologies that is already out of date.

6. Make child care free for all families below a certain income level to increase real wages and participation.

7. Investment heavily in research capacity development within the university system.

8. Invest heavily in apprenticeship positions via the TAFE sector.

9. Introduce a Job Guarantee for those workers than still are unable to get a job.

10. In the short-run, while the pandemic is wreaking havoc, pay all workers forced to isolate or to lose work due to lockdowns, their full wages to maintain incomes.

11. Pay all small business income for the same period.

12. Invest in renewable energy infrastructure – batteries etc to accelerate the closure of carbon-based electricity generation.

13. Eliminate tax incentives to invest in real estate (negative gearing etc).

14. Re-regulate the labour market to eliminate the gig economy – force employers to pay annual leave, sick pay, contribute to superannuation etc.

15. Restore all penalty rates to low-income workers.

16. Fund the states to ensure public transport becomes free to all users.

17. Create a public bank to reduce fees in the sector and channel investment funds into productive ventures. This will erode the 4-private bank cartel.

That set of initiatives is guaranteed to increase GDP growth rates, provide massive incentives for private savers to channel investment funds into productive capacity generation rather than financial speculation and real estate, and increase productivity growth.

Investing in people, in particular, is the best returning expenditure a government can actually engage in.

Gauging the extent of the collapse in work

One of the problems in working out how bad the labour market is relates to the impact of the JobKeeper wage subsidy program, which is distorting the Australian Bureau of Statistics figures.

Many workers are being counted among those officially employed even though they are not actually working.

In a recession, firms have two means of adjusting their employment numbers:

(a) Adjust hours worked.

(b) Adjust numbers employed.

We typically see hours worked adjusted first because it allows the firm to avoid expensive layoff and subsequent hiring costs when the recession is abating.

As a recession deepens, firms are forced to then layoff workers, as their sales do not recover and they encounter liquidity constraints.

The following table shows how these adjustments have played out relative to the peak in March 2020:

| Month | Employment Change (%) | Hours Worked Change (%) |

| April 2020 | -3.7 | -9.5 |

| May 2020 | 6.7 | -10.4 |

| June 2020 | 5.1 | -6.8 |

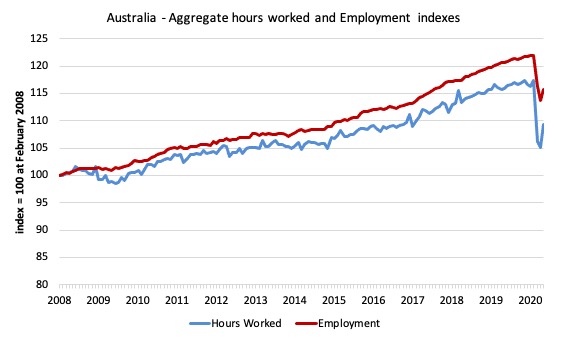

The following graph compares the Total Hours Worked and Total Employment indexed at 100 in February 2008 (the peak before the GFC).

You see that the GFC was mostly handled through hours being cut and employment outstripped hours ever since.

That is because there has been a bias towards part-time work over this period.

Increased government spending causes deflation

As an aside, we had a wonderful demonstration yesterday in Australia of how an increase in government spending can ’cause’ deflation, a falling price level.

Most economists consider that inflation is the process by which the growth in spending outpaces the capacity of the economy to match it with production of real goods and services, which on the face of it, is a reasonable proposition.

MMT economists do not contest that understanding – it is obvious that when the supply capacity is stretched beyond potential that increasing nominal spending, from whatever source, government and non-government, has to be rationed.

That rationing might take the form of increased order queues without any price movements.

But firms will also likely start pushing up prices to gain higher profits.

But MMT economists also stress that inflation can be driven by administrative processes – governments pushing up ‘user pays’ prices, over-100 per cent indexation rules, etc.

The latter is a particular issue in Australia with respect to health insurance premiums in Australia.

Yesterday, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released its quarterly – 6467.0 – Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia, June 2020 – which is a very useful perspective on the way in which prices impact on different types of households.

This release follows last week’s – 6401.0 – Consumer Price Index, Australia, June 2020 – which reported a substantial deflation for the June-quarter.

The All Groups CPI fell by 1.9 per cent for the quarter and 0.3 per cent for the year to June 2020.

The ABS said that:

The most significant price falls in the June quarter were child care (-95.0%), automotive fuel (-19.3%), preschool and primary education (-16.2%) and rents (-1.3%).

Which gives you a hint as to what was going on.

Yesterday’s release provided more detailed information for the study groups the ABS has articulated for its Selected Living Cost Indexes (LCIs):

For the June-quarter, the following summary was provided:

- Pensioner and Beneficiary -1.4 per cent

- Employee -2.6 per cent

- Age pensioner -0.8 per cent

- Other Government Transfer Recipient -1.9 per cent

- Self-funded Retiree -0.4 per cent

The main reason for these results is that the Australian government introduced free child care in early April, which impacted on “three of the five household types”.

They were initially intended to remain in place until June 28, 2020, but were extended until July 12.

The Government has now reinstated the ‘Child Care Subsidy and Additional Child Care Subsidy’ scheme, which will see significant increases in private outlays and a rise in inflation in the September-quarter.

The free child care should have been continued as part of a broader stimulus package. Cutting government spending, and, effectively cutting private sector real wages (as a result of the inflationary impacts of cutting that spending) during a massive economic crisis was not responsible government and will exacerbate any recovery.

But this clearly demonstrates that fiscal stimulus can, when ‘administrative pricing’ is involved, cause deflation.

Conclusion

Overall, we need leadership from government.

Neither major party is currently demonstrating that and the negative consequences will be long-lived.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The leadership know exactly what they are doing.

That’s putting foreign policy first instead of domestic policy like they have done for the last 50 years. Aka neoliberalism.

Was watching the flagship BBC news programme Newsnight last night regarding the bombing in Lebanon. So what were they saying ?

Let’s play buzzword bingo..

IMF, loans, structural reforms, privatisations and deregulate the banks.

That was it in a nutshell.

Yes, they will get help but they have to do the Chile blueprint rolled into the EU narrative. Everything we consider to be neoliberalism. In order to become a captive state like all the rest in the new geopolitical order.

So how far have we really come ?

The introduction of the ZW$ in Zimbabwe is a text book neoliberal central bank rollout – with 35% policy rates and a pegged currency to the USD.

And they have inflation at 700%, and a black market value for the ZW$ way out of line with the official peg. In other words they have recreated Venezuela in six months.

When all they really needed to do was follow the Buckaroo blueprint – so the government can provision itself. Actually having the banking system in a foreign currency is great when you’re starting up the new currency. Fewer dynamics to generate feedback harmonics.

Something Scotland should note. But probably won’t…

Bill you seem to have cut and paste the section “the government’s response has been inadequate” twice.

Yup, stack em high with $ debt. Keep raising rates and cause the crises that they can then do whatever they like with afterwards.

The Americans just treat every country they come across like they did with the native indians. Would China or Russia be any different ? I doubt it.

It’s all going to come to a head at some point, probably in the Pacific that Clinton wanted to rename the American sea. Long before Trump got there the yanks were bat shit crazy. Only now they have added paranoia to the mix.

MMT is terrible foreign policy – is the viewpoint of the war mongers. I’m glad to be nearer 60 than 20 and very lucky to be part of a generation that has never been ” called up”. There hasn’t been many generations who can say that.

Tik Tok the clock is ticking.

We do need leadership and leadership willing to engage with the science and the evidence.

Post-modernist politics where the truth does not matter is an existential threat to us all. Put it in bin.

The health science, climate science and modern monetary theory are not matters for opinion, they’re the basis for action.

Bill when do we get to vote you into the Senate?

Governments in the western world had months forewarning of the magnitude of the impending crisis and clearly a few hundred ceo’s may have as well, since that many seem to taken an early retirement in the weeks immediately prior to any emergency measures being taken.

The “planning” appears to have been for a scenario reminiscent of the sinking of the Titanic, first class first to the, less than adequate number of lifeboats.

What’s needed right now, to sound like a broken record, is something along the lines of a ten-point MMT plan, signed off on by the majority (if not all) of MMT economists, which sets forth the economic measures that should be taken by currency-sovereign nations–as well as those that can be taken by EU and other non-currency sovereign nations–to weather the coming Covid depression and emerge on the other side with healthier, more humane, more environmentally-sensitive societies. I’m talking about SPECIFICS fundamental enough to be understood by both government officials and the citizens they are supposed to serve. I believe the time will soon be upon us when it becomes evident to the vast majority that the current economic measures being taken are failing and failing miserably to meet a civilizational crisis. I expect that massive and relentless civil protest, resistance, and disorder–dwarfing the repercussions of the George Floyd murder–will erupt in many if not most nations (and especially in the U.S.) when some unforeseeable incident triggers the pent-up outrage of economic immiseration piled on top of a lingering lethal threat to personal and public health. So the time to draw up that MMT plan is NOW, in this period of relative calm, before the impending tsunami explodes into the streets. Bill can help to lead this, but he cannot do it alone. MMT economists must come together, work together, speak together ASAP as one clear and unified voice of sanity in a world on the verge of breakdown/meltdown/collapse.

Humanity’s terminal disease as a species: letting money take control rather than taking control of money.

After debating a fellow scientist on economics, i realize that mainstream economics is the yoke that enslaves people.

“I expect that massive and relentless civil protest, resistance, and disorder-dwarfing the repercussions of the George Floyd murder-will erupt in many if not most nations (and especially in the U.S.) when some unforeseeable incident triggers the pent-up outrage of economic immiseration piled on top of a lingering lethal threat to personal and public health.”

And combined with the virus, we may lose enough people that any discussion about economics may be rendered redundant for many generations. Sadly, I fear most people haven’t yet realised – or refuse to acknowledge – the magnitude of what we face.

What are our weaknesses and strengths?

Knowing what we now know – what would you have done on 31 December 2019 had you been in a position of influence?

You Australians might be lucky your leadership lacks vision. The US has a leader with plenty of visions about the course of this pandemic. It will soon be seen that the whole thing is just about to go away any day now. Those who lack vision just can’t see this and just can’t appreciate that the US response has been visionary from the outset and that we are first or last or whatever depending which way you hold up the charts our leader gets in between visions.

Militias’ Warning of Excessive Federal Power Comes True – But Where Are They?

An article by Amy Cooter Vanderbilt University

Shows just how mental America has become. How backward thinking nations have become since the rise of neoliberal globalism in the 80’s.

Militias and Second Amendment fox news believers who set up their own armies in the first place to protect themselves from government. Support Trump in suppressing peaceful protests. The majority being raving racists and right wing death squads. Who wouldn’t hesitate to be on the streets with their guns if the left were marching on Washington.

I come from a family of scholars, academics and writers, but regrettably have little of their talents, however I am reminded of an essay given to me a very long time ago be a cousin, whose father was the author.

Whilst being raised in a working class mining village a stone’s throw from the birthplace of Adam Smith and indoctrinated by a Calvinistic work ethic, I can well appreciate the good intentions of full employment and a job guarantee, can I just introduce a different notion to consider.

I appreciate it was written a long time ago, but I suspect it’s as relevant today as it ever was.

In Praise of Idleness

Bertrand Russell

LIKE most of my generation, I was brought up on the saying “Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do.” Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached. Every one knows the story of the traveler in Naples who saw twelve beggars lying in the sun (it was before the days of Mussolini), and offered a lira to the laziest of them. Eleven of them jumped up to claim it, so he gave it to the twelfth. This traveler was on the right lines. But in countries which do not enjoy Mediterranean sunshine idleness is more difficult, and a great public propaganda will be required to inaugurate it. I hope that after reading the following pages the leaders of the Y. M. C. A. will start a campaign to induce good young men to do nothing. If so, I shall not have lived in vain.

Before advancing my own arguments for laziness, I must dispose of one which I cannot accept. Whenever a person who already has enough to live on proposes to engage in some everyday kind of job, such as school-teaching or typing, he or she is told that such conduct takes the bread out of other people’s mouths, and is, therefore, wicked. If this argument were valid, it would only be necessary for us all to be idle in order that we should all have our mouths full of bread. What people who say such things forget is that what a man earns he usually spends, and in spending he gives employment. As long as a man spends his income he puts just as much bread into people’s mouths in spending as he takes out of other people’s mouths in earning. The real villain, from this point of view, is the man who saves. If he merely puts his savings in a stocking, like the proverbial French peasant, it is obvious that they do not give employment. If he invests his savings the matter is less obvious, and different cases arise.

One of the commonest things to do with savings is to lend them to some government. In view of the fact that the bulk of the expenditure of most civilized governments consists in payments for past wars and preparation for future wars, the man who lends his money to a government is in the same position as the bad men in Shakespeare who hire murderers. The net result of the man’s economical habits is to increase the armed forces of the State to which he lends his savings. Obviously it would be better if he spent the money, even if he spent it on drink or gambling.

But, I shall be told, the case is quite different when savings are invested in industrial enterprises. When such enterprises succeed and produce something useful this may be conceded. In these days, however, no one will deny that most enterprises fail. That means that a large amount of human labor, which might have been devoted to producing something which could be enjoyed, was expended on producing machines which, when produced, lay idle and did no good to anyone. The man who invests his savings in a concern that goes bankrupt is, therefore, injuring others as well as himself. If he spent his money, say, in giving parties for his friends, they (we may hope) would get pleasure, and so would all those on whom he spent money, such as the butcher, the baker, and the bootlegger. But if he spends it (let us say) upon laying down rails for surface cars in some place where surface cars turn out to be not wanted, he has diverted a mass of labor into channels where it gives pleasure to no one. Nevertheless, when he becomes poor through the failure of his investment he will be regarded as a victim of undeserved misfortune, whereas the gay spendthrift, who has spent his money philanthropically, will be despised as a fool and a frivolous person.

All this is only preliminary. I want to say, in all seriousness, that a great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by the belief in the virtuousness of work, and that the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.

First of all: what is work? Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid. The second kind is capable of indefinite extension: there are not only those who give orders but those who give advice as to what orders should be given. Usually two opposite kinds of advice are given simultaneously by two different bodies of men; this is called politics. The skill required for this kind of work is not knowledge of the subjects as to which advice is given, but knowledge of the art of persuasive speaking and writing, i.e. of advertising.

Throughout Europe, though not in America, there is a third class of men, more respected than either of the classes of workers. These are men who, through ownership of land, are able to make others pay for the privilege of being allowed to exist and to work. These landowners are idle, and I might, therefore, be expected to praise them. Unfortunately, their idleness is rendered possible only by the industry of others; indeed their desire for comfortable idleness is historically the source of the whole gospel of work. The last thing they have ever wished is that others should follow their example.

From the beginning of civilization until the industrial revolution a man could, as a rule, produce by hard work little more than was required for the subsistence of himself and his family, although his wife worked at least as hard and his children added their labor as soon as they were old enough to do so. The small surplus above bare necessaries was not left to those who produced it, but was appropriated by priests and warriors. In times of famine there was no surplus; the warriors and priests, however, still secured as much as at other times, with the result that many of the workers died of hunger. This system persisted in Russia until 1917, and still persists in the East; in England, in spite of the Industrial Revolution, it remained in full force throughout the Napoleonic wars, and until a hundred years ago, when the new class of manufacturers acquired power. In America the system came to an end with the Revolution, except in the South, where it persisted until the Civil War. A system which lasted so long and ended so recently has naturally left a profound impression upon men’s thoughts and opinions. Much that we take for granted about the desirability of work is derived from this system and, being pre-industrial, is not adapted to the modern world. Modern technic has made it possible for leisure, within limits, to be not the prerogative of small privileged classes, but a right evenly distributed throughout the community. The morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery.

It is obvious that, in primitive communities, peasants, left to themselves, would not have parted with the slender surplus upon which the warriors and priests subsisted, but would have either produced less or consumed more. At first sheer force compelled them to produce and part with the surplus. Gradually, however, it was found possible to induce many of them to accept an ethic according to which it was their duty to work hard, although part of their work went to support others in idleness. By this means the amount of compulsion required was lessened, and the expenses were diminished. To this day ninety-nine per cent of British wage-earners would be genuinely shocked if it were proposed that the King should not have a larger income than a working man. The conception of duty, speaking historically, has been a means used by the holders of power to induce others to live for the interests of their masters rather than their own. Of course the holders of power conceal this fact from themselves by managing to believe that their interests are identical with the larger interests of humanity. Sometimes this is true; Athenian slave-owners, for instance, employed part of their leisure in making a permanent contribution to civilization which would have been impossible under a just economic system. Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was rendered possible only by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technic it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization.

Modern technic has made it possible to diminish enormously the amount of labor necessary to produce the necessaries of life for every one. This was made obvious during the War. At that time all the men in the armed forces, all the men and women engaged in the production of munitions, all the men and women engaged in spying, war propaganda, or government offices connected with the War were withdrawn from productive occupations. In spite of this, the general level of physical well-being among wage-earners on the side of the Allies was higher than before or since. The significance of this fact was concealed by finance; borrowing made it appear as if the future was nourishing the present. But that, of course, would have been impossible; a man cannot eat a loaf of bread that does not yet exist. The War showed conclusively that by the scientific organization of production it is possible to keep modern populations in fair comfort on a small part of the working capacity of the modern world. If at the end of the War the scientific organization which had been created in order to liberate men for fighting and munition work had been preserved, and the hours of work had been cut down to four, all would have been well. Instead of that, the old chaos was restored, those whose work was demanded were made to work long hours, and the rest were left to starve as unemployed. Why? Because work is a duty, and a man should not receive wages in proportion to what he has produced, but in proportion to his virtue as exemplified by his industry.

This is the morality of the Slave State, applied in circumstances totally unlike those in which it arose. No wonder the result has been disastrous. Let us take an illustration. Suppose that at a given moment a certain number of people are engaged in the manufacture of pins. They make as many pins as the world needs, working (say) eight hours a day. Someone makes an invention by which the same number of men can make twice as many pins as before. But the world does not need twice as many pins: pins are already so cheap that hardly any more will be bought at a lower price. In a sensible world everybody concerned in the manufacture of pins would take to working four hours instead of eight, and everything else would go on as before. But in the actual world this would be thought demoralizing. The men still work eight hours, there are too many pins, some employers go bankrupt, and half the men previously concerned in making pins are thrown out of work. There is, in the end, just as much leisure as on the other plan, but half the men are totally idle while half are still overworked. In this way it is insured that the unavoidable leisure shall cause misery all round instead of being a universal source of happiness. Can anything more insane be imagined?

The idea that the poor should have leisure has always been shocking to the rich. In England in the early nineteenth century fifteen hours was the ordinary day’s work for a man; children sometimes did as much, and very commonly did twelve hours a day. When meddlesome busy-bodies suggested that perhaps these hours were rather long, they were told that work kept adults from drink and children from mischief. When I was a child, shortly after urban working men had acquired the vote, certain public holidays were established by law, to the great indignation of the upper classes. I remember hearing an old Duchess say, “What do the poor want with holidays? they ought to work.” People nowadays are less frank, but the sentiment persists, and is the source of much economic confusion.

II

Let us, for a moment, consider the ethics of work frankly, without superstition. Every human being, of necessity, consumes in the course of his life a certain amount of produce of human labor. Assuming, as we may, that labor is on the whole disagreeable, it is unjust that a man should consume more than he produces. Of course he may provide services rather than commodities, like a medical man, for example; but he should provide something in return for his board and lodging. To this extent, the duty of work must be admitted, but to this extent only.

I shall not develop the fact that in all modern societies outside the U. S. S. R. many people escape even this minimum of work, namely all those who inherit money and all those who marry money. I do not think the fact that these people are allowed to be idle is nearly so harmful as the fact that wage-earners are expected to overwork or starve. If the ordinary wage-earner worked four hours a day there would be enough for everybody, and no unemployment – assuming a certain very moderate amount of sensible organization. This idea shocks the well-to-do, because they are convinced that the poor would not know how to use so much leisure. In America men often work long hours even when they are already well-off; such men, naturally, are indignant at the idea of leisure for wage-earners except as the grim punishment of unemployment, in fact, they dislike leisure even for their sons. Oddly enough, while they wish their sons to work so hard as to have no time to be civilized, they do not mind their wives and daughters having no work at all. The snobbish admiration of uselessness, which, in an aristocratic society, extends to both sexes, is under a plutocracy confined to women; this, however, does not make it any more in agreement with common sense.

The wise use of leisure, it must be conceded, is a product of civilization and education. A man who has worked long hours all his life will be bored if he becomes suddenly idle. But without a considerable amount of leisure a man is cut off from many of the best things. There is no longer any reason why the bulk of the population should suffer this deprivation; only a foolish asceticism, usually vicarious, makes us insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no longer exists.

In the new creed which controls the government of Russia, while there is much that is very different from the traditional teaching of the West, there are some things that are quite unchanged. The attitude of the governing classes, and especially of those who control educational propaganda, on the subject of the dignity of labor is almost exactly that which the governing classes of the world have always preached to what were called the “honest poor.” Industry, sobriety, willingness to work long hours for distant advantages, even submissiveness to authority, all these reappear; moreover, authority still represents the will of the Ruler of the Universe, Who, however, is now called by a new name, Dialectical Materialism.

The victory of the proletariat in Russia has some points in common with the victory of the feminists in some other countries. For ages men had conceded the superior saintliness of women and had consoled women for their inferiority by maintaining that saintliness is more desirable than power. At last the feminists decided that they would have both, since the pioneers among them believed all that the men had told them about the desirability of virtue but not what they had told them about the worthlessness of political power. A similar thing has happened in Russia as regards manual work. For ages the rich and their sycophants have written in praise of “honest toil,” have praised the simple life, have professed a religion which teaches that the poor are much more likely to go to heaven than the rich, and in general have tried to make manual workers believe that there is some special nobility about altering the position of matter in space, just as men tried to make women believe that they derived some special nobility from their sexual enslavement. In Russia all this teaching about the excellence of manual work has been taken seriously, with the result that the manual worker is more honored than anyone else. What are, in essence, revivalist appeals are made to secure shock workers for special tasks. Manual work is the ideal which is held before the young, and is the basis of all ethical teaching.

For the present this is all to the good. A large country, full of natural resources, awaits development and has to be developed with very little use of credit. In these circumstances hard work is necessary and is likely to bring a great reward. But what will happen when the point has been reached where everybody could be comfortable without working long hours?

In the West we have various ways of dealing with this problem. We have no attempt at economic justice, so that a large proportion of the total produce goes to a small minority of the population, many of whom do no work at all. Owing to the absence of any central control over production, we produce hosts of things that are not wanted. We keep a large percentage of the working population idle because we can dispense with their labor by making others overwork. When all these methods prove inadequate we have a war: we cause a number of people to manufacture high explosives, and a number of others to explode them, as if we were children who had just discovered fireworks. By a combination of all these devices we manage, though with difficulty, to keep alive the notion that a great deal of manual work must be the lot of the average man.

In Russia, owing to economic justice and central control over production, the problem will have to be differently solved. The rational solution would be as soon as the necessaries and elementary comforts can be provided for all to reduce the hours of labor gradually, allowing a popular vote to decide, at each stage, whether more leisure or more goods were to be preferred. But, having taught the supreme virtue of hard work, it is difficult to see how the authorities can aim at a paradise in which there will be much leisure and little work. It seems more likely that they will find continually fresh schemes by which present leisure is to be sacrificed to future productivity. I read recently of an ingenious scheme put forward by Russian engineers for making the White Sea and the northern coasts of Siberia warm by putting a dam across the Kara Straits. An admirable plan, but liable to postpone proletarian comfort for a generation, while the nobility of toil is being displayed amid the ice-fields and snowstorms of the Arctic Ocean. This sort of thing, if it happens, will be the result of regarding the virtue of hard work as an end in itself, rather than as a means to a state of affairs in which it is no longer needed.

III

The fact is that moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary to our existence, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life. If it were, we should have to consider every navvy superior to Shakespeare. We have been misled in this matter by two causes. One is the necessity of keeping the poor contented, which has led the rich for thousands of years to preach the dignity of labor, while taking care themselves to remain undignified in this respect. The other is the new pleasure in mechanism, which makes us delight in the astonishingly clever changes that we can produce on the earth’s surface. Neither of these motives makes any great appeal to the actual worker. If you ask him what he thinks the best part of his life, he is not likely to say, “I enjoy manual work because it makes me feel that I am fulfilling man’s noblest task, and because I like to think how much man can transform his planet. It is true that my body demands periods of rest, which I have to fill in as best I may, but I am never so happy as when the morning comes and I can return to the toil from which my contentment springs.” I have never heard working men say this sort of thing. They consider work, as it should be considered, as a necessary means to a livelihood, and it is from their leisure hours that they derive whatever happiness they may enjoy.

It will be said that while a little leisure is pleasant, men would not know how to fill their days if they had only four hours’ work out of the twenty-four. In so far as this is true in the modern world it is a condemnation of our civilization; it would not have been true at any earlier period. There was formerly a capacity for light-heartedness and play which has been to some extent inhibited by the cult of efficiency. The modern man thinks that everything ought to be done for the sake of something else, and never for its own sake. Serious-minded persons, for example, are continually condemning the habit of going to the cinema, and telling us that it leads the young into crime. But all the work that goes to producing a cinema is respectable, because it is work, and because it brings a money profit. The notion that the desirable activities are those that bring a profit has made everything topsy-turvy. The butcher who provides you with meat and the baker who provides you with bread are praiseworthy because they are making money but when you enjoy the food they have provided you are merely frivolous, unless you eat only to get strength for your work. Broadly speaking, it is held that getting money is good and spending money is bad. Seeing that they are two sides of one transaction, this is absurd; one might as well maintain that keys are good but keyholes are bad. The individual, in our society, works for profit; but the social purpose of his work lies in the consumption of what he produces. It is this divorce between the individual and the social purpose of production that makes it so difficult for men to think clearly in a world in which profitmaking is the incentive to industry. We think too much of production and too little of consumption. One result is that we attach too little importance to enjoyment and simple happiness, and that we do not judge production by the pleasure that it gives to the consumer.

When I suggest that working hours should be reduced to four, I am not meaning to imply that all the remaining time should necessarily be spent in pure frivolity. I mean that four hours’ work a day should entitle a man to the necessities and elementary comforts of life, and that the rest of his time should be his to use as he might see fit. It is an essential part of any such social system that education should be carried farther than it usually is at present, and should aim, in part, at providing tastes which would enable a man to use leisure intelligently. I am not thinking mainly of the sort of things that would be considered “high-brow.” Peasant dances have died out except in remote rural areas, but the impulses which caused them to be cultivated must still exist in human nature. The pleasures of urban populations have become mainly passive: seeing cinemas, watching football matches, listening to the radio, and so on. This results from the fact that their active energies are fully taken up with work; if they had more leisure they would again enjoy pleasures in which they took an active part.

In the past there was a small leisure class and a large working class. The leisure class enjoyed advantages for which there was no basis in social justice; this necessarily made it oppressive, limited its sympathies, and caused it to invent theories by which to justify its privileges. These facts greatly diminished its excellence, but in spite of this drawback it contributed nearly the whole of what we call civilization. It cultivated the arts and discovered the sciences; it wrote the books, invented the philosophies, and refined social relations. Even the liberation of the oppressed has usually been inaugurated from above. Without the leisure class mankind would never have emerged from barbarism.

The method of a hereditary leisure class without duties was, however, extraordinarily wasteful. None of the members of the class had been taught to be industrious, and the class as a whole was not exceptionally intelligent. It might produce one Darwin, but against him had to be set tens of thousands of country gentlemen who never thought of anything more intelligent than fox-hunting and punishing poachers. At present, the universities are supposed to provide, in a more systematic way, what the leisure class provided accidentally and as a byproduct. This is a great improvement, but it has certain drawbacks. University life is so different from life in the world at large that men who live in an academic milieu tend to be unaware of the pre-occupations of ordinary men and women; moreover, their ways of expressing themselves are usually such as to rob their opinions of the influence that they ought to have upon the general public. Another disadvantage is that in universities studies are organized, and the man who thinks of some original line of research is likely to be discouraged. Academic institutions, therefore, useful as they are, are not adequate guardians of the interests of civilization in a world where every one outside their walls is too busy for unutilitarian pursuits.

In a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving, however excellent his pictures may be. Young writers will not be obliged to draw attention to themselves by sensational pot-boilers, with a view to acquiring the economic independence needed for monumental works, for which, when the time at last comes, they will have lost the taste and the capacity. Men who in their professional work have become interested in some phase of economics or government will be able to develop their ideas without the academic detachment that makes the work of university economists lacking in reality. Medical men will have time to learn about the progress of medicine. Teachers will not be exasperatedly struggling to teach by routine things which they learned in their youth, which may, in the interval, have been proved to be untrue.

Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia. The work exacted will be enough to make leisure delightful, but not enough to produce exhaustion. Since men will not be tired in their spare time, they will not demand only such amusements as are passive and vapid. At least one per cent will probably devote the time not spent in professional work to pursuits of some public importance, and, since they will not depend upon these pursuits for their livelihood, their originality will be unhampered, and there will be no need to conform to the standards set by elderly pundits. But it is not only in these exceptional cases that the advantages of leisure will appear. Ordinary men and women, having the opportunity of a happy life, will become more kindly and less persecuting and less inclined to view others with suspicion. The taste for war will die out, partly for this reason, and partly because it will involve long and severe work for all. Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen instead to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines. In this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish for ever.

I do apologise for posting the essay in full. I have a pdf version of the original text but it’s mostly ineligible, but there are various versions online and I think there is still a current print version.

The message I took away from this is that we really don’t have to do very much. Perhaps it’s best that we don’t try to change the world – just sit back and enjoy the place. Leave a shallow footprint as possible and just do enough to get by, whilst helping others to do the same.

I’m well aware that some are more capable than others. They carry the greatest burden – and gift, should they choose to use it wisely. Time moves much slower than our ambition. We have to temper our pace, organise ourselves in harmony with our environment and realise we are only a very small part in a much greater picture.

We can eliminate coronavirus if we cease all travel – air and sea passenger services especially. And if we all remain quiet for a while. Never before has idleness been more essential.

Good luck.

Mark, thanks for posting the entire Bertrand Russell essay, which is overflowing with humane commonsense wisdom that stands a pole apart from the neoliberal capitalist worldview. I suspect that the JG, if it is ever put into place, would soon become a popular option for employment in general, one obviously preferable to most lower level work in the private sector. Similarly, the public option in American health insurance would likely have provided an attractive alternative to private health insurance, which explains why Obama took it off the table at the outset of the health coverage debate. If there were public jobs available to all that provided minimally decent wages and minimally sufficient benefits coupled with JOB SECURITY, I suspect that many would take refuge in them, learn to live within their economic constraints, find ways to help each other in doing so, etc., to the point where private employment, except at much higher levels, would largely be unattractive. It would then be but a small next step to reduce work hours and make other humane adjustments to the JG, all of which would serve to further enhance its desirability over anything other than top tier private sector work. This possibility–PROBABILITY–is what I believe the neoliberals sense and fear about the JG–it being a foot in the door to compare (by actual experience) work life in the public sector to that in the private.

I think the majority of people want to do something productive with their life so that it provides some meaning and contentment, we’ve just imposed a measurement on that process that has no place there – money and wealth.

The most content person I’ve ever met was a 90 year old spinster who lived in a remote cottage in the west highlands of Scotland. In 1996, she had only recently been connected to the National Grid – but her water supply was still from the nearby burn and she still cut peat for the fire and stove. To do a house call would take me the four or five hours. She always had a pot of soup waiting – and incredible stories.

Jessie MacKinnon was one of the evacuees from St Kilda in 1930 – when she was just 12 years old. She was the only surviving child in her family – her mother had given birth to nine other children who died in infancy from tetanus.

You can search St Kilda on google if you haven’t heard of it before. The only city she’s visited was Glasgow – for a funeral and just one day. But she was far from parochial in her outlook. She had an old Robert’s radio and was extremely well read and had an incredible knowledge of world events.

But crucially, she was able to see them from a perspective long lost. I’m sure you know what I mean.

I am equally fortunate. I’ve had a productive, satisfying job helping people with foot problems, which served me very well. It has provided me with the time to develop my other interests – climbing, music and writing – and with the insight of others who have had different lives and experiences.

At the end of the day, all we have is our memories. Our secondary objective is to be able to recount those memories for the next generation, for they are important for them too. Living memory.

We have much to do, but we should also be able to enjoy and marvel at this miracle of a place all the same. I like the idea of a Job Guarantee – and I admire Bill’s ethics and motivation. We have much to do. But we can share the workload and not exhaust ourselves in the process. With MMT principles, all kinds of incentives are possible – 4-day weeks, a one year paid vacation/sabbatical every five years – material encouragement to self-fulfilment and creativity.

We don’t have to do very much. Just enough. There is another momentum that will enthral. If we are lucky – like Jessie – it will become second nature.

“Enough” is arguably the wisest, most beautiful word in the English language, and no doubt other languages have their equivalents. I would love to see MMT become the first school of economic thought to be more focused on the value of enough than on the value of efficiency. If it learns to do that, IMHO, its future is as bright as a blessing from on high.

Indeed. And an examination of “value” and “quality” would be equally beneficial, even if motorcycle maintenance became a thing of the past.

I do hope all of the MMT contributors take the time to read the essay. Bertrand’s outlook in 1935 was confined as much by the Gold Standard than anything else – had he known about fiscal capacity and fiat currency macroeconomics, then that essay would have been incredibly important, especially given global events at the time.

I still think it extremely relevant today. We have to change the way people think, what they can be motivated to do for the good of themselves and their community. If you combine the essay with your knowledge of economics and money, you have part of the blueprint.

Have a lovely weekend.

I think there is a direct series of cause and effects that led the world to where it is now. At least, pre-pandemic.

1] The US pegged gold at $32/oz. after WWII. Other nations pegged to the US$. The world was back on the gold standard.

2] The US promised to buy more of other nations’ stuff than they bought. So, the US had the largest trade deficit the world had ever seen.

3] Over time the US went for the greatest ever creditor nation (as a result of loans made in WWII) to being the world’s greatest ever debtor nation.

4] Other people and nations began to worry about how the US could pay its national debt and foreign trade debt.

5] Some of them caused a run on the US gold supply in 1971.

6] Nixon took the world off of the gold standard.

7] As a direct result many economists and leaders expected there to be high inflation n the US.

8] With the Vietnam War coupled with the Great Society programs, there was sort of high inflation.

9] The leaders of OPEC were a bunch of believers in the gold standard as the Only true basis of money.

10] They were, therefore, the strongest believers in the group that expected high inflation in the US$. They raised the price of oil in 1973 and embargoed the West over the war with Israel, or at least so they said.

11] The increased oil prices shot thought the US economy and caused inflation that *nobody* could stop. Businesses had to raise their prices because oil was part of the price of everything. So, seeing the inflation, OPEC raised prices more.

12] The US Fed. raised interest rates to reduce inflation. When this didn’t stop it (nothing could stop it), they raised rates more, then more, etc.

13] This resulted in Stagflation.

14] The stagflation was used as the reason to throw out the old economic theory and adopt Neo-liberalism as the new standard economic theory.

So, without that chain of events it is likely that neo-liberalism would NOT have been the standard model for the last 40 years.

.

Mark Russell, “it is unjust that a man should consume more than he produces”

Just wondering how this “unjustness” fits in with the remains of Shanidar I, a Neanderthal who during his lifetime clearly did consume more than he “produced” and still his kin cared for him during his earlier injuries and provided for him for him for years after he was clearly not able to provide for himself?

Sure this was in the context of a subsistence economy but still applicable to human economic systems generally. Even with in the subsistence economies of hunter gatherers, lore and social custom made sure everyone with in the band got fed out of what was gathered and hunted. In these sorts of societies and economies leaders were judged by how much they gave away rather than how much they acquired or penny pinched.

The premise is a bit too close to the premise of “unnütze Esser” in any case.

_______________________________________________________________

By the way bloody good article Bill.