With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Spending equals income whether it comes from government or non-government

It is now clear that to most observers that the use of monetary policy to stimulate major changes in economic activity in either direction is fraught. Central bankers in many nations have been pulling all sorts of policy ‘rabbits’ out of the hat over the last decade or more and their targets have not moved as much or in many cases in the direction they had hoped. Not only has this shown up the lack of credibility of mainstream macroeconomics but it is now leading to a major shift in policy thinking, which will tear down the neoliberal shibboleths that the use of fiscal policy as a counter-stabilisation tool is undesirable and ineffective. In effect, there is a realignment going on between policy responsibility and democratic accountability, something that the neoliberal forces worked hard to breach by placing primary responsibility onto the decisions of unelected and unaccountable monetary policy committees. And this shift is bringing new players to the fore who are intent on denying that even fiscal policy can stave off major downturns in non-government spending. These sort of attacks from a mainstream are unsurprising given its credibility is in tatters. But they are also coming from the self-proclaimed Left, who seem opposed to a reliance on nation states, and in the British context, this debate is caught up in the Brexit matter, where the Europhile Left are pulling any argument they can write down quickly enough to try to prevent Britain leaving the EU, as it appears it now will (and that couldn’t come quickly enough).

The latest Leftist salvo was published an article – It’s all going pear-shaped (August 24, 2019) – written by one Michael Roberts (who is actually some City of London economist and writes under cover – one of them).

On his blog he refers to himself as marxist economist. Which means what exactly?

I would also say that my career in economics has been inspired by the basic insights about Capitalism provided by Karl Marx (and Friedrich Engels) and the writers that followed in that tradition.

But I would also be sure to disagree with Michael Roberts assertion that “MMTers deny the validity and relevance of Marx’s key contribution to understanding the capitalist system: that is it is a system of production for profit; and profits emerge from the exploitation of labour power – where value and surplus value arises” (Source).

As one of the developers of MMT, I have always made it explicit that Marx’s ideas on class and exploitation lie at the basis of Capitalist dynamics and should be the starting point for a progressive understanding.

So it is hard at times to know what being ‘Marxist’ means, which is especially the case when we consider the post-modern distractions that made ‘Marxism’ appear recondite, to say the least.

So while the pursuit of profits in a class system clearly drives non-government investment behaviour, history shows that a deterministic interpretation and extrapolation of this behaviour independent of government is likely to mislead.

Social democratic movements (political, industrial, social) rose to counter the power of capitalist producers and expressed that counterveiling force in the form of government policy after the Second World War.

Yes, profit expectations drove private business investment, but those expectations became tempered, regulated, conditioned (choose your own word) by government impost.

For sure there was a continual resistance from Capital to the popularism of social democratic governments.

We know from released Australian Cabinet documents that in the 1960s the business lobbies were demanding the then conservative government deliberately create higher unemployment to reduce the capacity of the workers to realise wage demands.

Neoliberalism (as a catch-all term) rose in the 1970s as a political and economic strategy to address what had been summarily termed the ‘profit squeeze’.

And as we explained in detail in our recent book – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, September 2017) – that resistance from Capital was expressed and engendered through the state not by replacing the state.

The state was reconfigured and became an agent for Capital rather than a mediator between capital and labour, as it had been in the ‘full employment’ Post World War 2 period.

That conditions what I think about the role of the state and its capacities in a fiat monetary system.

The basic claim by Michael Roberts in the article cited above is that it is incorrect to think:

… that fiscal stimulus through budget deficits and government spending can stop ‘aggregate demand’ collapsing.

He thinks this idea – which I am calling a move to fiscal dominance – is gaining traction among economists (who mostly have changed their previous views) as it becomes clear that monetary policy “can do little or nothing to sustain capitalist economies in 2019”.

He lumps “Modern Monetary Theory economists” among this group.

Apparently, we “got very excited because Summers seemed to agree with” us about the need for fiscal dominance.

Well, let me say, as one of the original MMT economists I didn’t get excited at all about the attempt by Larry Summers to reinvent himself and cover his past history of myriad failures.

I don’t take anything that Summers says that agrees with what I write as ‘endorsement’ of MMT. He is not qualified to hand out such endorsements.

I just see a man who has a terrible track record in the profession across a number of dimensions (economist, policy advisor, university manager, etc) trying to be relevant when time has passed him by – more pathos really.

But I understand the nature of Michael Robert’s trying a sort-of MMT putdown to condition his readers to accept his argument, which, as you will see, has little substance.

His thesis is that no policy intervention – “nothing will stop the oncoming slump”.

That is categorical.

And his rationale?

That’s because it is not to do with weak ‘aggregate demand’ …

Some basics:

1. Aggregate demand is total spending in the economy.

2. Given the way we measure economic activity (as an aggregate of output and income produced per period), nominal (money) values of spending must equal income as an accounting statement.

3. If inflation is stable, then increased spending equals increased real income.

4. When we talk of ‘slumps’ (or recessions, which would constitute a serious slump) we are talking about a contraction in real spending and income.

5. An “oncoming slump” must therefore be the result of the growth of aggregate spending (‘demand’) falling behind the growth in productive capacity, which leads to cuts to production, unemployment, and, ultimately, recession if not curtailed.

It makes no sense to characterise a recession as being divorced from movements in aggregate spending.

There can be no recession if aggregate spending keeps pace with productive capacity growth and the spending that producers expect, which conditions their production decisions.

Michael Roberts says that “household consumption in most economies is relatively strong as people continue to spend more”, which is questionable – true to a point.

But in the case of Australia, the slowdown in GDP growth is being driven exactly by a slowdown in household consumption in the face of subdued business investment and an austerity obsessed federal government.

Further, in the case of the US, the contribution to real GDP growth from ‘personal consumption expenditures’ has been falling sharply since the middle of last year.

And in the UK, growth in household consumption expenditure has been in trend decline since 2016, with occasional solid quarters.

And in Japan, one could hardly say that household consumption expenditure has been a uniformly strong driver of growth and will slump again if the Government goes ahead with the scheduled increases in sales tax in October 2019.

I could go on.

His next point is curious:

The other part of ‘aggregate demand’, business investment is weak and getting weaker. But that is because of low profitability and now, in the last year or so, falling profits in the US and elsewhere.

Are we to take this to mean that aggregate demand in his analytical framework is the sum of household consumption and business investment?

That is the way it is written – household consumption and the “other part”.

Before we deal with that, it is true that business investment is weak in a number of economies.

This is partly because of in the tepid recoveries after the GFC, firms were uncertain of the continuity and strength of overall spending that they have determined they had enough capacity in place to deal with demand and didn’t want to take the chance in installing extra productive capacity.

Investment spending is asymmetric because it has an irreversibility quality. Once in place it is costly to abandon.

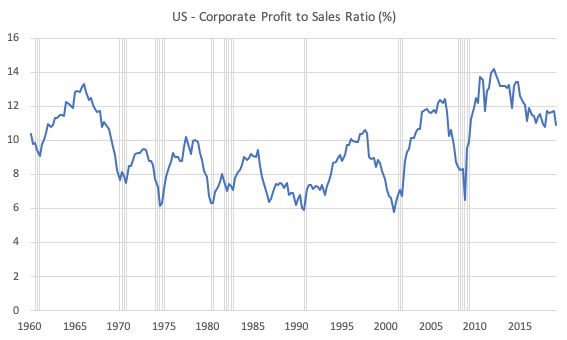

Michael Roberts produces a graph drawn from US national accounts that he says represents “US corporate profit margins” but which is really the “profits as a share of GDP”, which is not really a measure of the margin over sales.

Michael Roberts used GDP as an approximation to corporate final sales which is a fairly rough estimate.

There is some complex definitional issues regarding who gets the corporate profits (resident companies versus foreign subsidiaries) as against the incomes paid to generate them that I won’t go into here.

The point is that using “profits as a share of GDP” to measure profit rates can give some anomalous results.

A better measure for the US is provided within the National Accounts published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), but you have to do some calculations.

Table 1.14 in the Interactive Data app provides detailed data for ‘Gross Value Added of Domestic Corporate Business in Current Dollars and Gross Value Added of Nonfinancial Domestic Corporate Business in Current and Chained Dollars’.

Gross value added of corporate businesses (Line 1 of the Table) is the best measure of final sales of domestic corporations in the US.

This Table also provides data (Line 13) for “Profits after tax with IVA and CCAdj” which is domestic corporate profits after some inventory valuation and Capital Consumption Adjustments.

The following graph shows the more accurate measure of the US corporate profit margins from the March-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 2019.

As in the graph provided by Michael Roberts, I have added the NBER Recession bands (quarterly) in grey.

A close study shows some material differences.

I could also construct similar graphs for other countries including Australia. Any decline in profit margins is much less apparent in Australia (and non-existent in many industries), but I don’t want to digress to discuss that here.

While there has to be some relationship between declining profit margins (the ‘profit squeeze’) and economic downturns, given the importance of business investment, the graphs (mine and his) show that the timing of this relationship is highly variable and not consistent.

The answer to the puzzle lies in adding the other components of total expenditure which Michael Roberts ignores – government spending and net exports.

His aim in the article (and prior work) is to deny that government spending matters as a determinant of aggregate output and income generation.

He writes:

The Keynesians, post-Keynesians (and MMT supporters) see fiscal stimulus through more government spending and increased government budget deficits as the way to end the Long Depression and avoid a new slump. But there has never been any firm evidence that such fiscal spending works, except in the 1940s war economy when the bulk of investment was made by government or directed by government, with business investment decisions taken away from capitalist companies.

This statement is a denial of history.

First, what does “fiscal spending works” actually mean?

Does he want us to believe that if the government adds to its net spending when there is idle capacity that there is zero impact on total demand and income?

Second, there are many examples of the use of discretionary fiscal policy stimulus being used outside of the 1940s, to offset declines in non-government spending (particularly business investment spending).

Sometimes, that fiscal intervention is not sufficient – usually because governments are bullied into taking more conservative lines.

In other cases, the fiscal intervention clearly prevents recession even when business investment collapses and/or export revenue declines sharply.

Three cases are within our recent historical grasp.

First, consider China.

Regardless of its political system, China operates a fiat monetary system where the Chinese government is the currency issuer and they demonstrated during the early stages of the GFC that they know exactly what they are doing with respect to using that monetary supremacy to maintain growth as one component of spending collapses.

They sailed through the global crisis even though exports fell dramatically. In this blog – Where the crisis means death! (May 8, 2009) – I discussed the response of the Chinese government to the onset of the crisis and the sharp decline in their export revenue as spending in the advanced nations collapsed.

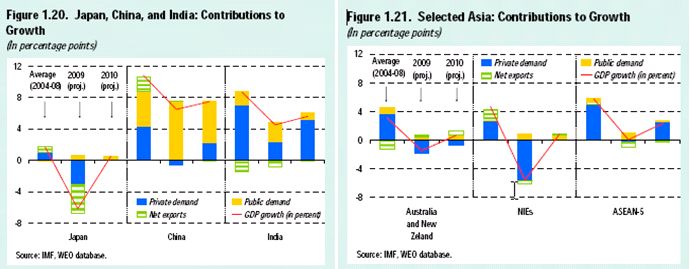

The IMFs Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific Report produced the following graph. It split the contribution to growth of public demand (net government spending), private demand and net exports for some selected Asian nations.

China stands out. Most people think of China’s growth coming from its burgeoning export sector. But it has a very strong domestic economy and a large public spending program.

In the text accompanying that graph, the IMF said that:

In China, GDP growth will also slow down notably from the average pace of the recent past. Still, the aggressive policy response is expected to support domestic demand and maintain growth at rates close to the level authorities consider necessary to generate jobs consistent with social stability. In particular, the massive program of public investment initiated late last year is expected to compensate for the decline in private investment and absorb productive resources no longer utilized in the tradable sector.

So the graph highlighted in the early stages of the crisis the importance of very large fiscal interventions.

No economy that trades is immune to the developments of their trading partners and certainly export revenue can fall sharply which creates some possible dislocation for the domestic economic activity.

But when the global financial crisis hit, the Chinese government redirected demand quickly into domestic expansion.

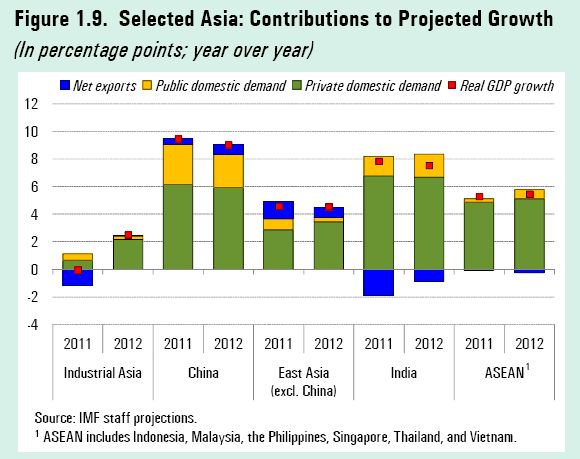

The following graph reproduces Figure 1.9 in the IMF publication and shows the contributions to real GDP growth (2011 and projected) by spending component – that is, next exports, public demand, private domestic spending (consumption and investment).

The IMF note in relation to this graph that:

The fundamentals for domestic demand in the region remain strong and are expected to cushion the impact of weaker external demand on overall growth for the rest of 2011 and in 2012

It is clear that the main driver of real GDP growth is as it was in the early years of the crisis (see graph above) – domestic demand. Net exports contribute a small component of real GDP growth which puts the popular conception that China is an export-led economy into an entirely different light.

Now, Michael Roberts might say that China is an exception because of its state-directed economy. And there is truth in that. Its fiscal interventions were much less open to domestic criticism.

But it doesn’t get away from the fact that fiscal policy worked!

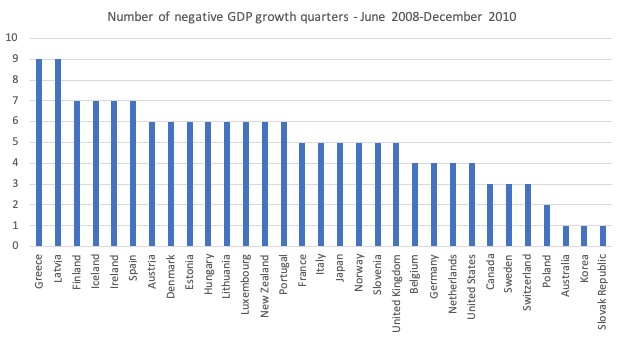

Second, consider Australia next, which was one of few advanced nations to avoid a recession during the GFC.

It produced a large and very early fiscal stimulus package which included cash payments to households and large infrastructure projects.

The Treasury provided the following – Briefing Paper which estimated that in 2008-09 the “contribution of the stimulus to GDP growth” was 1 per cent and in 2009-10 1.6 per cent.

The wrote that:

This translates into a level of GDP that is 23/4 per cent higher in 2009-10 than without the stimulus. The design of the stimulus package involves a staged withdrawal of stimulus, which subtracts 1.2 per cent from GDP growth in 2010-11.

On employment:

The peak impact of the stimulus packages … was the addition of 210,000 jobs and the level of employment remains higher through to the end of the forecast period.

The following graph shows the number of negative quarters of real GDP growth between June 2008 and December 2010, ranked by number. A recession is considered to be two-consecutive quarters of negative growth.

It is hard to get a coherent view of all the fiscal shifts in that time (given the time I have to write this today). The IMF publication – The Size of the Fiscal Expansion: An Analysis for the Largest Countries – estimated (in 2009) that:

… fiscal policy may have contributed 2-21⁄2 percentage points to PPP-weighted growth of the nine countries in 2008 and may provide 2-21⁄4 percentage points in 2009

The nine countries were Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, U.K., and the U.S.

My own analysis at the time suggested that the stimulus packages were delayed for too long and were not of a sufficient size to offset the cyclical shifts in non-government spending.

And when the stimulus packages were prematurely withdrawn growth slowed or went backwards as in the case of the Eurozone and the UK.

There is no doubt that even though the fiscal stimulus initiatives were usually too small and withdrawn too soon that they ‘worked’ to attenuate the decline in non-government spending.

In the case of Australia, they allowed our nation to avoid recession altogether.

Michael Roberts concludes by citing the example of Japan:

The irony is that the biggest fiscal spenders globally have been Japan, which has run budget deficits for 20 years with little success in getting economic growth much above 1% a year since the end of the Great Recession …

No irony here at all.

Japan experienced arguably the biggest property collapse in history in the early 1990s. It introduced a rather significant fiscal stimulus response and only experienced one-negative quarter of GDP growth.

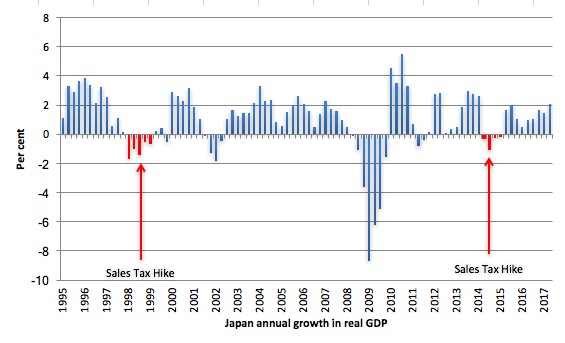

As I have explained previously – in this blog post for example – () – political forces panicked the Government and they introduced a sales tax hike in 1997.

I have written about the Japanese experience with sales tax rises before:

1. Japan is different, right? Wrong! Fiscal policy works (August 15, 2017).

2. Japan returns to 1997 – idiocy rules! (November 18, 2014).

3. Japan’s growth slows under tax hikes but the OECD want more (September 16, 2014).

4. Japan – signs of growth but grey clouds remain (May 21, 2015).

5. Japan thinks it is Greece but cannot remember 1997 (August 13, 2012).

Everytime they hike sales taxes, it ends in misery – spending falls and economic activity comes to a crashing halt.

They saw that in 1997. And again in 2014.

In April 2014, the Abe government raised the sales tax from 5 per cent to 8 per cent.

After the sales tax hike, there was a sharp drop in private consumption spending as a direct result of the policy shift. At the time, I predicted it would get worse unless they changed tack.

It certainly did get worse. Consumers stopped spending and the impact of static consumption expenditure was that business investment then lags.

Here is the history of real GDP growth (annualised) since the March-quarter 1994 to the March-quarter 2015. The red areas denote sales tax driven recessions.

In both episodes, these recessions were followed by a renewed bout of fiscal stimulus (monetary policy was ‘loose’ throughout).

In both episodes, there was a rapid return to sustained growth as a result of the fiscal boost.

Nothing could be clearer.

Fiscal policy has been very effective in Japan.

Trying to equate low growth rates in a nation with an ageing population and very high saving ratios with a lack of effectiveness is invalid.

For another view, examine the evolution of the Japanese unemployment rate. In the years after the property crash, the rate rose modestly to around 3.5 per cent, which given the scale of the crash was an incredible testament to the effectiveness of fiscal policy.

And then, later, during the GFC, it only peaked at 5.4 per cent (August 2009) and then fell relatively quickly to its current (low) level of 2.4 per cent.

I could continue to offer countless examples of historical episodes where fiscal intervention works in both directions. But time is out today.

Conclusion

Michael Roberts claims that any renewed fiscal stimulus “won’t work”.

The problem that he ignores history and basic logic.

Spending equals income.

When I go to the shop after work the checkout operator doesn’t ask me whether I work for a public wage or a private wage.

What do you think would happen if, say, the UK government announced it was going to upgrade infrastructure (say school or hospital buildings) throughout the north of England and were calling for tenders? Do you think it is realistic to assume there would be no tenders received at all?

Or that there would be no private leverage off that activity as a result of the renewed construction and procurement?

What do you think would happen if the UK government announced a Job Guarantee – an unconditional job offer to anyone at a socially-inclusive minimum wage? Do you think no one would turn up for a job?

Some of the newly created income would go into imports. Some into increased savings. But there would be growth – undoubted.

In a later post I will consider the import and saving leakages, which are, in themselves, interesting.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I have been following Michael Roberts blog for some time now and I have even “defended” MMT in the comments sections there. I find his insights interesting and I would like to make some comments.

– Michael doesn’t believe that, already operating businesses, make additional investments in prevision of future sales, but that they invest (or not-invest) as an answer to the previous profits with a margin of, more or less, a year. So, profits come first, and investment later. He has done some studies (even one book) showing it. Personally, in my limited experience working in corporations, I have the feeling that he’s right.

– From my readings of his blog, and one interaction with him there, my interpretation is that he thinks that fiscal policy can’t be enough to offset the fall in businesses investment. I could be wrong, but I think that the reasoning is that, if enough fall in investment was offset by the government, profitability would not recover and the government should keep investing indefinitely in bigger and bigger percentages of the economy until, at some point, it would not make sense talking about a capitalist economy anymore.

-That leave us with the question “why profitability would not recover?”. My understanding of Michael position is that the final cause of profitability (in his Marxist interpretation) is the exploitation of workers. An aggressive fiscal policy would benefit workers (reducing unemployment, reducing household debt and in general making life easier) would delay the recovery of exploitation, ergo, of profitability.

I hope I have not misinterpreted Michael positions too much. I really would enjoy, and, I’m sure, would learn a lot, if you two (Bill and Michael) have some kind of debate on those issues.

I have also engaged Michael in comment section debate.

He does not use data carefully and does not understand some macroeconomic details that are very important (as Bill explains above), and when flaws in his presentation of data are pointed out, he digs in.

He has misrepresented Bill’s own words on multiple occasions. When I pointed out that he had an incorrect interpretation of the JG, he digs in.

Roberto, it is true that firms want to make profits before they invest in further sales. But a firm cannot make any profits if it does not first commit resources (i.e. investment). There is no axiomatic truth to saying profits precede investment – it is a dynamic interaction. It is not some sort of fundamental truth, unlike the accounting identities which MMT takes as its starting point. But what he says sounds good and seems to have hooked alot of people, and if it grows too much then an MMTer may some day have to read his book and debunk it.

The idea that profitability will not recover from government spending sounds clever but makes no sense. If the government spends enough to cover what needs to be done and including provision for savings/profit, then someone is going to do the work and someone (either workers or capitalists) will get that profit money. What is the logical mechanism that prevents this? Roberts does not engage with simple logic like this: he goes back to his worldview and then says you are missing the point.

In any event, if the sort of infinite spiral that Roberts talks about actually existed, then surely he would be able to point to one detailed concrete example of it in the real world.

But apparently (based on my interaction with him) you will only find out all the answers if you read his book. What a crock.

Could we get some links to those “Australian Cabinet documents” from the 1960s which show business lobbies demanding higher unemployment?

In a couple of weeks I have to teach the Phillips Curve and its alleged “menu of policy choices.” These documents would support the idea that these “policy choices” are not mere technocratic options.

Thank you very much.

“Michael doesn’t believe that, already operating businesses, make additional investments in prevision of future sales, but that they invest (or not-invest) as an answer to the previous profits with a margin of, more or less, a year. ”

How would he explain the case of startups – take Amazon, for instance – that do MASSIVE investments while recording losses, and take years to become profitable?

More likely the ongoing business assumes that current trends will continue, and if sales are rising, it invests. It would be hard for a profitable business which takes its fiduciary duty seriously to take any different view. The case of the startup shows that businesses – all of them – do indeed invest based on their view of the future. It’s just that some use a different analysis to decide their view of the future.

Anthony (Thursday, August 29, 2019 at 21:08), unfortunately I’m not qualified to defend Roberts arguments, but, In my opinion, it’s very easy to see where he is coming from.

He’s a Marxist and he believes that the most important economic law in the current system is the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. He see this as a trend in capitalism that produce its periodic crisis and that finally will bring its demise. If someone say that have solved the business cycle (and in a way MMT does) that would be an attack to the core of his believes of how the economy works. I don’t think that makes him a “crok” and it’s hardly constructive to call him so.

You say that “a firm cannot make any profits if it does not first commit resources” but I could ask you where those resources come in the first place if not from profits. It seems to me, that the only way to solve this question is to look at the data, which Roberts claims have done. Again, I’m not qualified to argue about that.

Anyway, an important criticism of MMT that I really have not answer for (maybe the only one) is “where crisis come from?”. They come from a fall in aggregate demand, but what produces that fall? The “animal spirits” thing doesn’t work for me, neither does the “desires saving of the private sector”. Roberts answer: a fall in profits.

Incidentally, another question that have been in my mind lately is: why a so strong resistance to Keynesian stimulus (and by extension to MMT) from the business interest?. It can’t be just ignorance. If those policies recover the economy, shouldn’t business interest to be asking for them instead of bitterly opposing it?

Well, there go the two cents of a dilettante. Again, I hope I’m not misrepresenting Roberts opinions (or anyone else).

Great article. Very educational.

As for Japan, if they have always pushed the economy in recession with sales hike and then had to attenuate it later with deficit spending.

Why don’t they do away with sales hike in the first place?

Nevermind, I got my answer from a linked article here. Great articles.

Some people differentiate between “Marxian” and “Marxist”, as in “Marxian Economics”. From what he has written from time to time (including here), I would venture to call Bill a “Marxian economist”, or at least one strongly influenced by Marxian economics. I would not venture to call him a Marxist. Partly because I too do not really know what that means, but also because I think that Bill accepts Marx’s analysis of capitalism and what’s wrong with it, but does not necessarily accept Marx’s prescriptions for what to do about it. Because Bill has told us very precisely where he stands politically,

( https://billmitchell.org/blog/?page_id=2 )

I would guess that he supports a mixed economy but with a strong (and controlling) public sector. In this vision, capitalism exists side by side with publicly-owned entities, and capitalists are free within certain restrictions to do what they like, but the government can always step in (and capitalists need to know that) if they seem to be getting out of control. Government will always act for the greater good of the greatest number, in contrast to capitalism working for the enrichment of a relatively small number of elites.

This is something like the system that we had in the UK in the second world war, with the government being in complete control of the economy (as well as of the military), but with capitalist firms (large and small) being allowed to continue, and even get rich (although subject to extra taxation).

Because the war had been such a shattering experience, affecting probably every single family in the country to some extent, this war economy footing continued for many years, with rationing only ending in 1954 (i.e. 3 years into the first post-war Conservative government). One would not be surprised that “war socialism” (to use AJP Taylor’s phrase) would have continued under the 1945-1951 socialist government of Clement Attlee. But the post 1951 Conservative governments left much of what Attlee had done intact. The NHS remained in public hands. So did the railways, and most of the energy industry. Council houses continued to be built in large numbers.The expression “we are all socialists now” (surprisingly) dates from the late 19th century (and was probably meant ironically by its originator), but it could have been used literally in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, and even later. Leading conservatives such as Harold Macmillan, Rab Butler, and Ian MacLeod were probably to the left of Tony Blair.

I do know know anything about Michael Roberts. I’m more familiar with Richard Wolff, who speaks prolifically and entertainingly on Youtube from a Marxist perspective. Since he has appeared on one YT video with Stephanie Kelton, he must know (and presumably understand) the basic premises of MMT. But I get the impression he doesn’t accept them. e.g. he still uses the language of taxation funding government spending. Whether that is true of Marxists generally, I don’t know. Perhaps Marxists’ problem with MMT is that MMTers seem content to allow capitalists to carry on (although not carry on without limitations), whereas Marxists supposedly want to eliminate capitalism.

Dear Roberto,

Marx was not a prophet and he tried to analyse the system existing around 1850-1860 in England, Germany and France. The idea of “the tendency of the rate of profit to fall” was not even invented by him. I would see an element of “wishful thinking” in assuming that capitalism will destroy itself. It hasn’t yet. But the main issue is that instead of understanding the (dialectical) logic of Marx and Engels and trying to apply it to the economy and society in 2019, some people treat Marx precisely as a prophet. It did not end up well in the Eastern Europe.

In regards to understanding what profits come from I suggest reading Kalecki. In a closed economy without a government sector, profits are equal to capitalists spending and investment. The work of Kalecki has been incorporated into MMT. What we need to do is to build a stock-flow consistent model of the whole economy. We can easily get a system in a stable state, reproducing itself, with a constant rate of profits. One of the earliest models has been built by Kalecki himself (in “Theory of Economic Dynamics”). If you re-read the main blog post you will see that it doesn’t matter who spends, what matters is how much and on what. If we understand that money is endogenous and reject the loanable funds theory (I am afraid that some Marxist still believe in it), we will see that people may spend what they haven’t earned yet, that governments can create spending power out of nowhere and that some earnings will leak from the circuit of money-capital in the form of liquid savings (Marx would refer to that form of capital as either “monetary capital” or “fictious capital”, if we apply the Labour Theory of Value here, these are still claims mostly on someone’s labour). Basically all we need is to model the closed circuit “as is” not just philosophise what would happen if all the profits were re-invested. All of this has been incorporated into models developed by Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie (in “Monetary Economic”), but SFC models do not properly incorporate multiple social classes – yet (this is going to be fixed). In the “real world”, the capitalists will usually not overinvest, the last episode of global overinvestment was the dot com bubble which burst around 2001 (please graph Tobin’s Q rate to see this). Yet the GFC was much worse. The GFC was caused by the rise and then fall of autonomous investment in housing stock, financed by mortgage loans underpinned by the ever rising valuation of land (until it collapsed).

The real issue facing modern capitalism is different to the problem of falling profit rate, stunting the investment (as in the Goodwin model). The system is demand driven (see the “value realisation problem” in Marx). The capitalist class is winning the class struggle and national income distribution has shifted towards the rich. This has it turn shifted the bias point of the whole economic system towards a “secular stagnation”, the trajectory of the economy is below the “potential” growth determined by the progress in technology. Because of a different spending propensity of the social classes. As a consequence the rate of technological progress in the West (which is difficult to measure, but there is some anecdotal evidence) is also slowing down.

It is true that government spending can always stimulate the economy with spare productive capacities. The rich will then keep accumulating even more monetary claims of someone’s labour, until the working class realises that the parasites are actually not needed for anything if they just hoard money and don’t efficiently allocate resources by investing in fixed capital – what would lead to increasing the taxes to remove the redundant monetary savings, destabilising the financial system.

The rich don’t like this idea because this would upset the system based on the prevalent social inequality and may even lower the rate of profits. So they won’t fix the underlying problem of deficient aggregate demand because they don’t like the solution (described above by Bill in the main blog post). Here lies the true dialectical contradiction. The capitalist West will therefore further stagnate and wither, not being able to address the global environmental issues until it’s too late for all of us, while half-socialist China is overtaking the US in terms of technology and overall social development. (I mentioned a few years ago the article written by late Andy Grove in 2010, predicting this outcome).

The reaction of the American oligarchy is obvious, they are furiously pressing the “destroy and obliterate the competitor” button. But regardless of desperate attempts of people like Trump and Pompeo to “wriggle free” by seeding more conflicts around the world and throwing more money onto the military-industrial complex, the trajectory of stagnation of the West won’t change without addressing the fundamental income inequality issue, just by applying tariffs and reducing taxes. The money spent on the so-called defence leaks from the circuit, the same is true about tax cuts for the richest. The imports have shifted from China to Vietnam – how good is this?

The capitalist West is like an impotent pervert who overdosed on Viagra. His problem can’t be fixed by snorting more cocaine.

Also by blindly following the loanable funds doctrine, spreading the musings about the falling rate of profit and promoting the Goodwin model of the business cycle, the so-called Marxists (and to an extent, despite all the denials, SK), perpetuate the myth that pre-existing monetary capital belonging to capitalists is socially necessary to sustain the economy. Without the capitalists’s capital (generated through the accumulation of profits) the working class will also die. Also the state can only spend that pre-existing monetary capital which has to be borrowed from the rich (as increasing the taxes would upset the investors). But our grandchildren will have to repay that debt. So we are all screwed up because the revolution is coming late.

The most hated part of the MMT is the observation that the state can create monetary capital and spend it for the benefits of the whole society, creating public goods (as in China). There will be no hyperinflation, just severe hyperventilation of so-called financial commentators from the City.

Adam K. Quite a Post!

Roberto asks:

“where those resources come in the first place if not from profits”.

This morning I was thinking about Iran as it was in the 1950’s, with its vast newly discovered oil reserves…and its first ever (!) democratically elected government. We all know the story – a coup engineered by the CIA and MI5.

Obviously the resources belonged to Iran, but Iran needed oversees development capital; hence the coup, to ensure all the profits went to US and British interests.

Australia has experienced a similar style of exploitation of its huge gas reserves: Australian gas is now more expensive for local consumers than for consumers in Japan.

Many other examples: eg, the world’s biggest goldmine in Papua – the locals wear an environmental disaster, and the profits go to overseas company shareholders. The Niger delta etc etc.

So that’s where the resources are, the question is: how much value should accrue to owners of the development capital (technology)?

Roberto:

” “where crisis come from?”. They come from a fall in aggregate demand, but what produces that fall?”

Short answer: the private sector banking casino…..ie, speculative asset value increases (Ponzi schemes)., without sufficient government oversight.

Note: there is no actual reduction in *real* available resources, or real “effective demand* at the beginning of a recession, so the recession must be caused by speculators withdrawing funds from overheated (falsely valued) asset markets, resulting in a large number of counterparties with failed derivative trades ie instability in the entire baking system (eg Lehman’s bankruptcy).

Hi Roberto,

It’s quite clear to me that you have not read enough of Bill’s blog. Bill has plenty of articles discussing why crises originate. The simple answer is: it depends on the crisis and it is ridiculous for anyone to claim to have a single theory for each crisis. But Bill has alot of data showing that many crises come after a fall in aggregate demand usually starting with austerity-type behaviour by the government.

You have suggested that resources “come from” profits and asked where else they come from. I’m not sure this makes sense.

Let’s be clear here. Profits are excess financial claims that private entities have, which in our system can be traded for real resources. Profits are *not* the resources themselves. The real resources exist independently of the monetary system, and we use the monetary system to decide how to employ the real resources. Real resources, when employed productively, produce more real resources. That is nature. Money and profits do not produce things themselves, but they set the direction for what and how and for who we produce things.

I think Roberts *believes* that you cannot distinguish between the real resources and the money in analysis, which is what leads to you thinking that profits = resources. But this is simply wrong: money is not a real resource, it is a creation of government/law, and modern monetary theory seeks to understand how modern money interacts with the real resources.

If you cannot come up with a compelling response from Roberts’ work, I suggest you start to question Roberts and explore MMT more, rather than questioning MMT and exploring Roberts.

To expand on Adam K.’s excellent post and strictly speaking, “Marxism” is the philosophy of “dialectical materialism” (Marx is considered the first materialist philosopher, not the first macro-economist). As for the dialectic part Marx & Engels held that one could not, as Hegel tried, deduce the actual course of events from any “principles “. It is the principles that must be inferred from the events. In applying their philosophy to the study of the history of mankind, they came up with their class theory or “historical materialism” and in looking through this lens at the economy of their time, they came up with their excellent and prescient criticism of the capitalistic system of their time.

Having said this, I find no fault in an approach that “infers principles from events” instead of assuming universal rules that defy reality. In fact, we have often criticized the dogmatism and refusal to abandon ideology in modern macro. On the other hand, as Adam pointed out, Marxist dogmatists refuse to acknowledge that Karl was a man of his time and that they should have moved on from his era. For example, I read somewhere that, in an exchange with Liebknecht, Marx expressed his elation about the dawn of electrification because he thought it would shake the coal-based production establishment so hard, that the revolution would be brought about even faster than it would have either way. He thought the burden of production would fall off the back of the working class and socialist utopia would come one step closer. Well, consumerism and globalisation said otherwise. Nevermind the fact that in a world with today’s incredible productive capacity but dwindling ressources it would be sensible to talk about the limits of “growth” and not only about the property of the means of production and the distribution of the wealth they generate.

“The capitalist West is like an impotent pervert who overdosed on Viagra. His problem can’t be fixed by snorting more cocaine.”

This is genius, Adam. However, I’m thinking “cocaine” in this case is more war and that a “Tony Montana’esque” amount is about to be snorted.

Cheers

i thought marx thought that falling rates of profit was a consequence of capital appreciation.

Not rising and falling with the trade cycle .

Very sympathetic to the materialist and power analysis of marx but over the long

period of capitalism is their evidence of a general fall in profitability.

Wishful thinking lurks on left right and centre of politics. It is the stuff of dreams.

A pedant writes: That would more likely to have been MI6 – you know, the crowd of cowboys that employed the (fictional) James Bond, and whose existence was never owned up to until comparatively recent times.

MI5’s job is a bit different: They look for reds under the bed here at home, and spy on protest groups, trade unionists, and anyone else who might disturb the status quo even ever so slightly.

Not that it makes much difference: to use a phrase of my father-in-law’s: “They all p** in the same pot” – or more politely, they all went to the same (elite) schools and they all have the same establishment prejudices.