I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Where the crisis means death!

Today I have been working on a project for the Asian Development Bank concerning regional development and macroeconomic risk management in the Central Asian countries (all the “stans” plus a few others). I have also been reading a lot of the development economics literature lately, which is generally a place that the neo-liberal troglodytes really run amok. It certainly focuses one’s attention. In the advanced countries the media focuses on our own losses. In Australia, a lot is written about superannuation losses. And journalists, who largely ignored the fact that during the boom we still had around 10 per cent of our willing workers without enough work – wasted and excluded, are once again talking about unemployment. But overall, the public debate is not at all focused on how the current economic crisis is damaging the weakest of the weak in far off lands and killing people.

While the current economic crisis started as a financial problem it has now become a “real” crisis in that it is affecting production and employment. It is a misnomer to keep calling it the GFC given its huge spillovers into the labour market now. But the acronym has caught on and its saves typing!

In the advanced world, we tend to get obsessed with our own problems which are real enough. Clearly, the recession will worsen the lot of our own disadvantaged citizens significantly and reinforce the disadvantage that the neo-liberal policy regimes have inflicted on them. But when you consider the data more generally and understand what is happening in Africa and Asia you get a broader insight into how unhinged the global economy has become during the neo-liberal years. In fact, you quickly start to understand that the global economic meltdown it hitting the poorer regions of the world more quickly and more strongly than the advanced world might ever care to contemplate.

Tim Colebatch, the Melbourne Age opinion writer in his recent article – The hidden pandemic, argued that “the real victims of the global financial crisis are the poorest of the poor”. He asks:

How did a crisis that began in plush, carpeted offices on Wall Street spread to the remotest villages of Africa, the mountains of Latin America and the farms of Asia? … Those most brutally affected by the global financial crisis … will be people who had nothing to do with it. They will be poor people all over the world who are forced back into hunger and extreme poverty because the flow of money into their countries has been cut off.

These economies did not have direct exposure to the financial problems that have battered the banking sector in the first-world economies. The crisis has been transmitted to these economies by the way that they have become dependent on the advanced nations via trade and migrant workers. This dependence is one the worst aspects of this neo-liberal era.

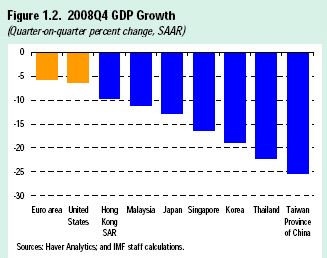

The IMFs Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific Report, shows that Asia excluding China and India has seen the size of their economies (measured by GDP) shrink by 15 per cent in the December 2008 quarter (annualised). The IMF is forecasting a further deterioration this year.

This graph is taken from the IMF Asia Outlook Report and shows the December quarter GDP growth figures for various Asian countries against the Euro Zone and the US.

Remember Australia recorded a -0.1 per cent growth in GDP for December, so we would barely be on the bar chart!

The loss of income in the poorer nations is staggering.

The IMF also conclude that the reason that the Asian economies are now being hit so hard lies in their “exceptional integration with the global economy.

Much of Asia relies heavily on technologically sophisticated manufacturing exports, products for which demand has collapsed”. I will come back to this later.

In terms of the scale of suffering, the World Bank noted that:

The recent food crisis threw millions into extreme poverty, and the prospect of much slower growth in developing countries is now likely, in turn, to slow the pace of poverty reduction. Estimates of the additional number of people trapped in extreme poverty in 2009 as a result of the financial crisis range from 50 to 90 million … The number of chronically hungry people in the world, which rose in 2008 because of the food crisis, is set to exceed 1 billion in 2009, reversing gains in fighting malnutrition and making investment in agriculture all the more important.

So the GFC is now interacting in a deadly way with the aftermath of the recent escalation in food prices sent more people into starvation. We should also recall that the food crisis has been driven by the advanced nations insatiable desire for energy to drive their cars and other contraptions and the so-called “greening of energy sources” via bio fuels which just turned food into fuel so that the advanced world could get fatter while the poorer nations buried their starving citizens.

It is also interesting to note that the IMF Regional Economic Outlook Report claim that “this severe impact was unexpected … [because] … before the crisis the region was in sound macroeconomic shape, and thus in a strong position to resist the pressures emanating from advanced economies”. Which tells you something about their assessment of what constitutes a “sound macroeconomic shape”. They define it along neo-liberal lines where the governments have privatised public wealth; deregulated markets; toughened welfare provision and pursued budget surpluses. You will probably have worked out by now that I have no sympathy at all with this position.

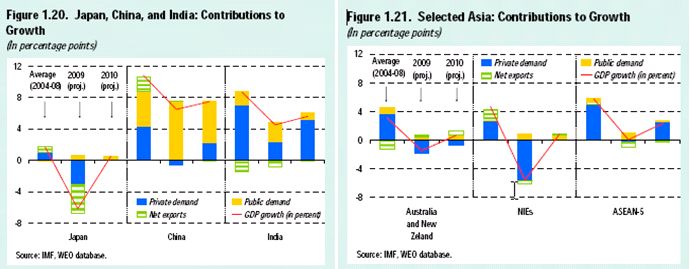

The next graph is taken from the IMF Report noted above. I thought it presented an interesting picture by splitting the contribution to growth of public demand (net government spending), private demand and net exports. China stands out. Most people think of China’s growth coming from its burgeoing export sector. But it has a very strong domestic economy and a large public spending program – its called “nation building”.

Nations need to be continually built and the comparison between China’s performance with Japan (with virtually no public sector) and the performance of Australia and New Zealand, which have only miniscule growth originated from public spending, is compelling.

The IMF Report notes in that:

In China, GDP growth will also slow down notably from the average pace of the recent past. Still, the aggressive policy response is expected to support domestic demand and maintain growth at rates close to the level authorities consider necessary to generate jobs consistent with social stability. In particular, the massive program of public investment initiated late last year is expected to compensate for the decline in private investment and absorb productive resources no longer utilized in the tradable sector.

So the graph highlights, in my view, the importance of very large fiscal interventions. My Chinese friends tell me there is no discussion over there about the country drowning in debt and all of that nonsense. They know full well that they are sovereign in their own currency and can deficit spend to further their sense of public purpose. I am not advocating that all the policies of the Chinese government are sound. Clearly not! But they do have a much more sophisticated understanding of the opportunities that they have as a monopoly supplier of their currency than our Government has. And they are taking those opportunities more than other nations around them that are caught in and are being choked by the neo-liberal web imposed on them by the advanced nations.

One problem facing the poorer nations is that commodity export prices have fallen significantly. This will bite us quite badly next year as the new prices start to reflect in the new export contracts. But for the dirt-poor nations, they have become reliant on primary commodity exports to earn foreign exchange to service the massive debts that they have to organisations such as the IMF. They don’t have much else to sell.

The so-called development push engineered by the big world organisations such as the IMF, the OECD and the World Bank has taken a very nasty tack over the last 20 years or so. The recently fashionable “new monetary consensus” (that underlies monetary policy formulation in most of the major countries) has claimed that high inflation undermines economic growth and this has been thrust down the throats of all nations by these internation organisations. The upshot has been that monetary policy has become the dominant macroeconomic policy tool focused almost exclusively on maintaining a low inflation environment.

Relatedly, fiscal policy has been eschewed by the funding contracts that the IMF, for example, has forced onto the poorest nations. The conditions attached to any developmental funding have concentrated on privatisation, deregulation, and fiscal consolidation, which has severely limited the capacity of these nations to conduct nation building of the type that Australia enjoyed in the early Post-World War II period.

While the members of neo-liberal governments in Australia in recent times have sought to undermine the Welfare State that they themselves enjoyed as kids growing up in the 1950s and 1960s (full employment, adequate income support etc), the advanced countries have funded these international institutions (like the IMF and the World Bank) to impose regimes on the poorest countries which would have prevented us from developing if they had have been imposed on us way back then. It is a cruel spite that accompanies the neo-liberal rhetoric.

The research evidence (references available on request) shows that inflation and growth are unrelated when inflation is below 40 per cent. Even the World Bank has acknowledged that truly damaging inflation does not start until about 40 per cent. Other research findings show that: (a) low inflation is not associated in general with high growth; (b) hyperinflation is, in general, associated with low growth; and (c) moderate rates of inflation, 20-30 per cent per year, have been associated with rapid growth quite often.

I am not saying that high inflation is desirable. But there is little evidence that inflation at the moderate rates that have prevailed in recent times in most countries around the world has any significant harmful effects on output, employment, growth, or the distribution of income. The evidence certainly does not justify the types of policy frameworks that have been imposed on the poorest nations by the bullying international institutions.

The other aspect of this new approach to development has been the export-led growth movement. The aim is to stabilise the exchange rate (or better still take the currency sovereignty off the nation by forcing dollarisation onto them – that is, forcing them to use the USD as their currency). The typical method used in many nations is to target inflation, reduce budget deficits, and encourage exports. This is exactly what the IMF has thrust on the poorest nations around the world and why they are now suffering so badly as export volumes and prices collapse.

This has all been dressed up within a changing development economics debate. Early approaches were based on the view that a nation had to accumulate productive capital to underpin economic growth by some osmotic process of technology transfer and “trickle down effects”. These approaches failed to solve world poverty and gave way to perspectives linking structural trade impediments (the structuralists) and the more powerful dependency theories (called international dependence theories). The latter emerged as a powerful force in development thinking in the 1960s and 1970s and emphasised the fact that poor countries were roped into dependent relationships with the developed world who used their raw materials and labour for their own profit. I am simplifying a complex literature here. The idea was that poor countries were never going to develop as long as they were in these dependence relationships with the advanced world.

However, it is hard to keep the conservative free market lobby down and by the 1980s the neo-liberal experiment started to dominate policy making throughout the advanced world. The so-called third world debt crises in the early 1980s which really showed how dependent the poorer nations had become on the aspirations of capital in the advanced nations provided the entree for the neo-liberals to take over development policy as well.

The claims were that the poor countries were being hamstrung by government intervention which prevented private markets from functioning efficiently. The emphasis shifted to privatising government enterprises and eliminating trade barriers (which were put up to protect the infant local industries). The neo-liberals also forced a freeing up of global investment which allowed the capital from advanced countries to flow around the world with minimal regulations and a diminished sense of social responsibility.

Growth strategies then focused on moving significant parts of the subsistence economies into the “market sector”. Subsistance agriculture gave way to cash crops which then flooded the world and drove down prices. We enjoyed the cheap food but the reduced income forced these nations to then go the IMF for further loans to help service the development assistance loans. The conditions on the so-called Structural Adjustment Packages were onerous. Countries like Mali lost all their forests (as cash crop exports) and now suffer terrible land degeneration and have nothing left to sell.

The traditional sectors in these economies were devastated as the advanced world forced “modernisation” onto them. Indigenous populations have seen their livelihoods expropriated by these processes. For example, their lands taken over by firms from the advanced countries who are pursuing carbon credits under emission trading schemes so they can continue to pollute in their own countries.

And when the advanced countries fail the shocks to the poorest nations are huge and they have very little structure in place to deal with them. Tragically their citizens starve and die.

Not a happy story at all.

Saturday Quiz

The next edition will be available sometime tomorrow afternoon. Put your thinking caps on!

Dear Bill,

I am not a professional economist so please forgive the mistakes which I may make in this post.

I only managed to read the last 2 post so the answers I am seeking might be in what had been written earlier.

You have mentioned that “printing” money in Australia would not result in any serious adverse consequences. You also mentioned that balancing government spending by selling bonds doesn’t serve any real purpose.

Wouldn’t it lead to inflation at a certain time in the future? Not because of the excessive amount of the money on the internal market as I understand that the deflationary debt deleveraging process is taking place. But because of the foreign currency markets. The currency will become less attractive to foreign investors and instead of paying 1.77 AUD/EUR the exchange rate might be for example 4 AUD/EUR. (Well EUR may one day adjust as well) This would instantly lead to inflation as petrol and other imported goods will go up. However over time manufacturing of goods may actually become profitable in Australia again.

I lived in a country where there was a bout of hyperinflation after the collapse of the centrally planned economy and the experience wasn’t good at all. The capitalist system was introduced with largely positive effects. The medicine administered by IMF and prof Sachs didn’t kill the economy, we had really strong stomachs. The social consequences were serious (endemic poverty is affecting some social groups there even now) but there was no alternative as the communist economy had already disintegrated before 1989. What happened in Russia (and Central Asian countries) at that time was another story and I would call it a real disaster.

So from my own experience I couldn’t say that hyperinflation was good. You mentioned that inflation < 40% shouldn’t be a problem, what if it spins out of control like in Germany in early 1920-ies? You may argue that this won’t happen and I will argue that this may not be bad at all in our context.

Wouldn’t it be actually beneficial to at least some groups of people in Australia from a very long time perspective? It would kill the “middle class” for sure and remove the false “wealth”. (Disclamer: I am not middle class as I am a stupid migrant with limited assets). In my opinion it depends how we define what is good for people. I think that he mission of official economics has been defined as maximising the consumption at any cost (environmental or human). That’s why the US government supported exporting US Treasuries and importing everything else. By the way – they (and us) have exported our jobs as well. I think that Poland in 1989-1991 isn’t a good model of what may happen. Argentina could be: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argentine_economic_crisis They had run a massive fiscal deficit and they had had a trade deficit. After the devaluation they started exporting goods and the economy powered ahead. So it wasn’t bad for everyone – it was good for the working class.

What really worries me is not a transitional drop in the consumption level (obviously I am not talking about crossing the poverty threshold but not buying more plasma TVs). What worries me is the permanent collapse in manufacturing in Australia. An economist may say – this is good, we are post industrial. So we have to accept the fact that cars can be made only if countries where wages are below $1000/month (you know what country I am talking about, where Fiat cars are made). I would argue that artificially strong Western currencies encourage wasting resources like oil which are irreplaceable. I cannot comprehend what is good in driving a 4WD car to work in the city or flying 10000 km every year to enjoy holidays . It looks cool but our children will live in the world without many of the nice toys we are enjoying no longer exist.

When I read your “10 points” from the previous post I was terrified as “printing money is no problem” may be an unusual statement from an economist. (I read it in the context of my experience with hyperinflation). Today I think that you are right – but for different reasons. There is inflation that we have to have and there is no other way of forcing people to waste (“consume”) less. There is no other way of forcing businesses and people to actually invest in energy-efficient technologies which do exist now. Petrol must cost $6/litre . Also – there is no other way of removing the post-colonial exploitation of third world countries as the commodities and products they make are under priced. (Yes the adjustment process will be more painful for them not for us but I don’t believe in redistribution).

I think that the process is inevitable because we cannot live forever in the the world where the US only exports financial services, we have mines, Arabs produce oil and China makes everything else. What may happen is probably a depression (the “middle class” will not give up in the short term) followed by the adjustment of Western currencies (a bout of hyperinflation) which will happen anyway because of the imbalance I mentioned above. The massive global exchange rate adjustment. Then and only then the new economical order may be established (if everything doesn’t melt down in a war).

Does it make sense or am I wrong?

Dear Adam

Thanks for your detailed comment. There is a lot in it.

First, if you read my work carefully you will see that I never use terms like “printing money” – government’s do not spend by printing money. They spend by crediting bank accounts (or issuing cheques that end up in bank accounts) – that is they add to bank reserves. Whatever else happens that is how the government spends every day (whether it is running a surplus or deficit). You might like to read – Quantitative Easing 101 for further discussion.

Second, why would the AUD become less attractive to overseas investors if the country was highly profitable, had great public infrastructure, had full employment, had stable prices, had good public health and education systems, etc? Sounds like the perfect currency that you would want to hold financial assets in or better still undertake investment in productive capacity to get in on the “profit train”.

Third, I cannot comment on the country that the IMF saved without knowing which country it is.

Fourth, hyperinflation is bad! I also didn’t say that inflation < 40 per cent shouldn’t be a problem. I noted that the researchers that have tried to find a relationship between inflation and real growth have only found it to be negative (that is, high inflation hurts real GDP growth) once it gets above 40 per cent. There are many reasons why you would want to maintain low and stable inflation.

Fifth, we could argue about Argentina. There problems largely originated in the early 2000s because they ran a currency board linked to the $US, which meant they voluntary lost their currency sovereignty. Once the crisis hit and they abandoned that arrangement and re-empowered fiscal policy then strong growth occurred. It isn’t how you represent it.

Sixth, I have no disagreement with you about our dependency on cars ( I ride a bike a lot).

Seventh, my ten points never mentioned that “printing money is no problem”. Governments do not spend by printing money – repeat after me, Governments do not spend by printing money! There is no reason we need any inflation right now. We can attain full employment and rebuild our public spaces without inflation and by running permanent deficits as long as the nominal injection of net government spending is equal to the leakage from the spending system brought about by non-government saving. That level of net spending (deficit) will not be inflationary but will support output and jobs. That is what we have to get into the heads of the politicians who have been conditioned by the neo-liberals to associate any deficits with inflation. That is categorically an untrue association. Hyperinflation will occur if any nominal spending (public or private) continuously outstrips the real capacity of the economy to absorb it. We are not where near that situation at present.

Finally, I think you are correct in thinking that there will be a major structural alignment in the world order over the next 20 years or more. China will get bigger and dominate the world economy like the US has done up until now. India will also continue to grow. The shift in energy demand will be profound and will impoverish the middle classes in many countries who have prospered through access to relatively cheap oil because China and other emerging countries have been so poor. Fundamental re-thinking will have to be made to accommodate these shifts. We are being let down by our governments (in advanced countries) who are not leading us into this new future. The best thing that we can do is to build our human capital capacity. Large investments in research and other capacities to build leadership in the new green world that will emerge out of all of this and beyond. That will need a massive public presence (therefore, significant budget deficits) and it is time we got over the idea that the private market has the strategic intelligence to provide the path into the future. The Chinese Government certainly knows what its role is in all of this and it is doing a much better job of looking after the future “economic” concerns of its citizens than we are.

best wishes

bill

Its good to see a post on developing countries, but I was wondering if you could expand on the role (if any) a job guarantee could play in developing countries as this post seems to be more about what the neoliberals did wrong rather than alternatives. I accept your arguments for the job guarantee being suitable in Australia or other developed nations but was wondering if it would work in cases where:

*the government has a limited ability to collect taxes and thus is constrained in creating demand for its currency.

*there is a high rate of corruption and thus the funding for a job guarantee gets stolen before it reaches the unemployed.

*the economy is a small economy dependent on trade for its food supplies and thus is more exposed to currency shocks which limits its ability to guarantee employment above a subsistence level of income.

Also I’ve read some work on Argentina’s ‘jefes’ limited job guarantee program but all the stuff I’ve found is at least a few years old so if you know of any more recent literature any links would be appreciated.

Dear Stuart

I will write a separate blog about the applicability of employment guarantees to developing countries. As mentioned I am doing work for the ADB at present in Central Asia on this topic although I am unable to really talk about it in any detail as yet. But in general, I have done work for the International Labour Office last year in South Africa on public works programs and I can talk about that. I am also giving a talk in New York next month to a big gathering of UNDP and related officials about the role of employment guarantees in developing countries.

Your points are the ones commonly raised and I will respond to them separately sometime soon. But you might want to read up about the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) which is provides millions of Indians with guaranteed work to reduce poverty. It faces all the problems you mention and many more but still is delivering benefit. These schemes are not perfect but are better than not implementing them.

best wishes

bill

Bill

Is there a link for the UNDP conference? I hadn’t heard about it.

Dear Bill,

Yesterday there was a very interesting yet brief discussion about fairness on Radio National by two economists. One of these people brought up the point that employees also take a risk (as human capital) and not only employers.

Ian McCauley

Department Of Business And Government, University Of Canberra

Mark Crosby

Associate Professor, Melbourne Business School

http://www.abc.net.au/rn/saturdayextra/stories/2009/2563325.htm

This reminded me of comments you have made (also in your response above) along the lines that a more equitable society (economy) would be a more productive (in the broader sense) one. I guess that if there was also more equity between countries then something similar would apply, eg if there was fair trade rather than just free trade.

It would be nice to have a post on this topic.

Cheers

Graham

Bill, you promised to provide references on request showing that any inflation below 40% is irrelevant for growth. I am curious 🙂 Could you please provide them either here or to my email. Thank you