Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

An MMT-Green New Deal and the financial markets – Part 1

Next week, I am attending a meeting which I hope will finalise discussions I have been having with some key prospective partners in putting together a major MMT-Green New Deal initiative in Australia which will have global ramifications. It will bring together MMT with climate action and indigenous rights interests. We propose to begin a ‘roadshow’ in November to start our campaign. Our discussions to date have been very productive and we will issue a ‘White Paper’ in the coming months to articulate what we conceive as a jobs-first, equity-first MMT-Green New Deal might look like. This work will also form the basis of talks I am giving in the coming month throughout Europe and the UK. I have already started sketching elements of my thinking on this topic under the category – Green New Deal – which also contains a long history (now) of relevant commentary. Today, I am focusing on another element that I consider to be a core part of a progressive MMT-Green New Deal campaign – dealing with unproductive financial markets. I am not for one minute thinking any of the analysis today (or any of the GND stuff) is likely to be implemented without a massive and lengthy struggle. I think I understand vested interests. So a valid retort to the ideas is not to accuse me of being politically naive. My role, as an academic, is to work through things and lay out blueprints to guide directions of activity based on that thinking. It is not to assess the likelihood of success of the blueprints being implemented. I sort of see these blueprints as being benchmarks – to assess where we are at and how far it is to go. And as debating vehicles which define what opponents have to address. But, moreover, I do see them as being guides for campaigning strategies, which can then be implemented by those who know more about those things than I ever will. This is a two-part series.

Keynes and ‘long-term expectation’

In John Maynard Keynes’ – The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money – we learned (long ago) in his discussion in Chapter 12. The State of Long-Term Expectation, that capitalist investment decisions depend on “the prospective yield of an asset”.

That return takes into account “future events which can only be forecasted with more or less confidence”.

These future events include “the strength of effective demand from time to time during the life of the investment under consideration” and other facts such as possible cost fluctuations.

He termed these guesses the “state of long-term expectation”.

Keynes noted that the problem is that the “development of organised investment markets … which facilitate investment but sometimes adds greatly to the instability of the system.”

He wrote:

In the absence of security markets, there is no object in frequently attempting to revalue an investment to which we are committed. But the Stock Exchange revalues many investments every day and the revaluations give a frequent opportunity to the individual (though not to the community as a whole) to revise his commitments. It is as though a farmer, having tapped his barometer after breakfast, could decide to remove his capital from the farming business between 10 and II in the morning and reconsider whether he should return to it later in the week. But the daily revaluations of the Stock Exchange, though they are primarily made to facilitate transfers of old investments between one individual and another, inevitably exert a decisive influence on the rate of current investment.

He was clear that there was a lot of daily ‘wealth shuffling’ going on in the financial markets which distorts the choice between long term productive investments and shorter-term speculative investments.

He noted that “organised investment markets” generated a sense of security among investors because ” the only risk he runs is that of a genuine change in the news over the near future” rather than committing to a “old-fashioned type … decisions largely irrevocable, not only for the community as a whole, but also for the individual” – by which he was meaning investments in large productive infrastructure (factories, plant etc).

In other words, the short-term fluctuations in the financial markets are “unlikely to be very large” and are thus “reasonably ‘safe'” as long as “convention” is maintained (habits and behaviours).

The investor “need not lose his sleep merely because he has not any notion what his investment will be worth ten years hence”.

He believed that these properties of financial markets undermined the possibility of “securing sufficient investment” (in productive ventures).

Why?

1. The growth of financial products meant that “real knowledge in the valuation of investments by whose who own them or contemplate purchasing them has seriously declined”.

2. “Day-to-day fluctuations in the profits of existing investments, which are obviously of an ephemeral and non-significant character, tend to have an altogether excessive, and even an absurd, influence on the market.”

3. “the mass psychology of a large number of ignorant individuals is liable to change violently as the result of a sudden fluctuation of opinion due to factors which do not really make much difference to the prospective yield” – the lemmings charging over the cliff mentality.

4. “the energies and skill of the professional investor and speculator … are, in fact, largely concerned, not with making superior long-term forecasts of the probable yield of an investment over its whole life, but with foreseeing changes in the conventional basis of valuation a short time ahead of the general public.”

That is, the financial markets have emerged not to provide for general public well-being, which historically required broadening the scope and quality of long-term productive capital, but, rather to extract as much as possible financially in the shortest period of time for specific interests.

He noted that it was rational (“not the outcome of a wrong-headed propensity”) for people to behave in this way – “an inevitable result of an investment market organised along the lines described”.

But while it was rational to pursue short-term ‘liquidity’ gains – none of the “maxims of orthodox finance … is more anti-social than the fetish of liquidity, the doctrine that it is a positive virtue on the part of investment institutions to concentrate their resources upon the holding of ‘liquid’ securities.”

This ‘fetish’ ignores the well-being of the “community as a whole”.

It has engendered a culture where the:

… actual, private object of the most skilled investment to-day is ‘to beat the gun’ … to outwit the crowd, and to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow.

He considered that conceps such as long-term value disappear in these markets:

For it is, so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs – a pastime in which he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late, who passed the Old Maid to his neighbour before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops. These games can be played with zest and enjoyment, though all the players know that it is the Old Maid which is circulating, or that when the music stops some of the players will find themselves unseated.

These markets are like casinos – eventually losses are incurred.

They also undermine the probability of long-term productive investment, which:

… needs more intelligence to defeat the forces of time and our ignorance of the future than to beat the gun.

Less intelligence … and anyone “who is entirely exempt from the gambling instinct” finds the “game of professional investment” to be “intolerably boring”.

Taken together, these factors lead to markets being organised which create a dominance of “speculation … forecasting the psychology of the market” over “enterprise … forecasting the prospective yield of assets over their whole life”.

Not only is there a misallocation of investment resources to short-term speculative ventures, but, also, the increased risk of speculative “bubbles” harming “a steady stream of enterprise”:

When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done. The measure of success attained by Wall Street … regarded as an institution of which the proper social purpose is to direct new investment into the most profitable channels in terms of future yield, cannot be claimed as one of the outstanding triumphs of laissez- faire capitalism – which is not surprising, if I am right in thinking that the best brains of Wall Street have been in fact directed towards a different object.

Keynes provided some suggestions for “mitigating the predominance of speculation over enterprise”.

1. the financial market “casinos should, in the public interest, be inaccessible and expensive”.

2. “introduction of a substantial government transfer tax on all transactions might prove the most serviceable reform available”.

3. “make the purchase of an investment permanent and indissoluble, like marriage”.

4. “The only radical cure for the crises of confidence which afflict the economic life of the modern world would be to allow the individual no choice between consuming his income and ordering the production of the specific capital-asset …”

He also considered that in the case of productive investments in say buildings – “the risk can be frequently transferred from the investor to the occupier, or at least shared between them, by means of long-term contracts”.

Further:

In the case of another important class of long-term investments, namely public utilities, a substantial proportion of the prospective yield is practically guaranteed by monopoly privileges coupled with the right to charge such rates as will provide a certain stipulated margin. Finally there is a growing class of investments entered upon by, or at the risk of; public authorities, which are frankly influenced in making the investment by a general presumption of there being prospective social advantages from the investment, whatever its commercial yield may prove to be within a wide range, and without seeking to be satisfied that the mathematical expectation of the yield is at least equal to the current rate of interest,-though the rate which the public authority has to pay may still play a decisive part in determining the scale of investment operations which it can afford.

In other words, when assessing public infrastructure investment “commercial yield” should not come into it.

I have written about that in the past, for example – Public infrastructure does not have to earn commercial returns (December 20, 2010).

The “general presumption of there being prospective social advantages” should always guide public infrastructure spending.

The neoliberal period has marked the shift away from that logic towards user-pays, commercial returns, private BOOT arrangements, all of which skew the type and scope of investments.

Coupled with the austerity bias and the downplaying of fiscal policy and we end up with diminished investments in essential infrastructure, while trillions get poured in the financial market speculation.

Keynes preferred solution – yes, published in 1936, is apposite today:

I expect to see the State, which is in a position to calculate the marginal efficiency of capital-goods on long views and on the basis of the general social advantage, taking an ever greater responsibility for directly organising investment …

He didn’t trust the ‘markets’ to correctly price in these long-term advantages and that “fluctuations in the market estimation ” of the returns on capital … will be too great to be offset by any practicable changes in the rate of interest.”

Which meant that he was “somewhat sceptical of the success of a merely monetary policy directed towards influencing the rate of interest” in influencing sensible investment behaviour.

These insights are, of course, at the centre of the debate now – the growing acceptance of the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position that reliance on monetary policy has not been a success and that a period of fiscal dominance is emerging.

Part of that shift in policy focus should be to frame the challenges of the Green New Deal in a much more sensible way – avoiding ridiculous questions such as ‘how are we going to pay for it’ and statements such as ‘we cannot afford it’ when the proponents are constructing those questions purely in terms of not having ‘enough currency’ to facilitate the required real resource shifts.

Growth of financial markets

Clearly, Keynes would have been astounded by what has happened over the last several decades in the proliferation of financial markets and the increasingly unproductive nature of their activities.

On February 4, 2019, the Basel-based Financial Stability Board, which says it “is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system”, published its latest – Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2018 – which is also accompanied by the supporting datasets.

In assessing the likelihood of “bank-like financial stability risks” arising (what they term a “narrow-measure of non-bank financial intermediation”) the, latest report (the 8th in its series since the GFC) shows that:

1. “The narrow measure of non-bank financial intermediation grew by 8.5% to $51.6 trillion in 2017, a slightly slower pace than from 2011-16.”

2. “The narrow measure represents 14% of total global financial assets.”

3. “Collective investment vehicles (CIVs) with features that make them susceptible to runs continued to drive the overall growth of the narrow measure in 2017.”

4. “In 2017, the wider “Other Financial Intermediaries” (OFIs) aggregate, which includes all financial institutions that are not central banks, banks, insurance corporations, pension funds, public financial institutions or financial auxiliaries, grew by 7.6% to $116.6 trillion in 21 jurisdictions and the euro area, growing faster than the assets of banks, insurance corporations and pension funds. OFI assets represent 30.5% of the total global financial assets, the largest share on record.”

The terminology has shifted to “non-bank financial intermediation” from “shadow banking” to massage favourable public perception. But the reality remains.

And increasing number of banks are reliant on “loan provision that is dependent on short-term funding” (speculative) and the proportion is growing.

The FSB introduced what they called ‘macro-mapping’, which uses aggregate data to compile financial risk indicators for the so-called Shadow banking system.

The broad measure includes all institutions in the financial sector except banks, insurance companies and pension funds.

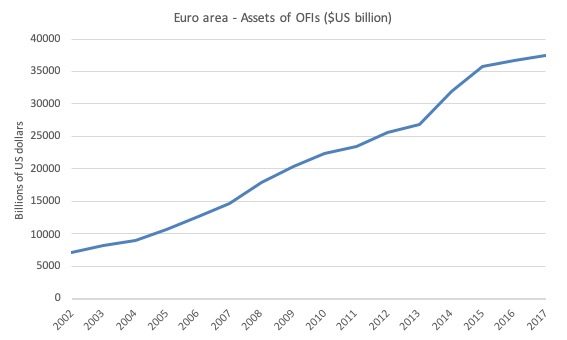

I used the FSB data to compile the following graphs for the Eurozone.

The first graph shows the growth of assets held by the OFIs from 2002 to 2017.

By 2017, total assets held by OFIs were $US37,423.1 billion having grown by 430 per cent since 2002. Similar graphs can be compiled for any number of companies.

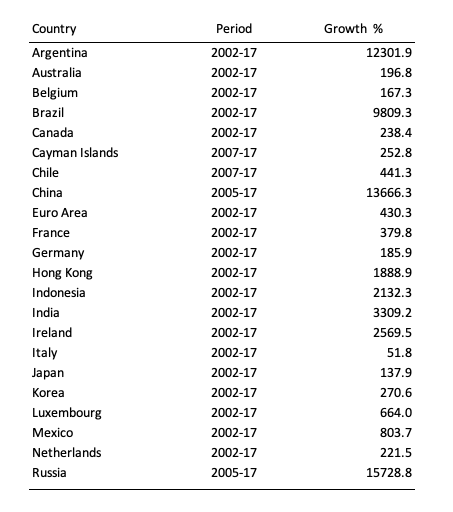

The following table shows the overall growth rates in OFI assets for the nations (groups) and periods that the FSB publishes data:

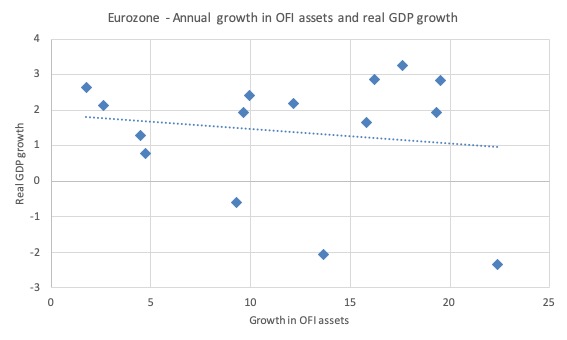

And just in case you might think otherwise, the next graph shows the cross-plot with the growth in OFI assets on the horizontal axis and the real GDP growth rate between 2002 and 2017 for the Eurozone.

The dotted line is a simple linear regression. While simplistic it would be hard to get a positive relationship out of this data between these variables using more sophisticated techniques.

You can see that when real GDP growth was negative (2008 and 2009 and 2012) the OFI assets growth was strong.

The relationships shown in these graphs are common across most jurisdictions.

The focus of regulators has been on trying to come up with risk assessment frameworks.

They obviously avoid the deeper question as to why we should tolerate the growth of this sector, when the outputs are as Keynes knew full well – not conducive to long-term well-being.

And it is clear to date that regulators have not been able to contain the risks that meltdowns in these markets cause damage to the real economy – output, employment, workers’ incomes and job security.

Conclusion

In Part 2, I will discuss what I see as the way forward if we are to integrate financial market reform within a MMT-Green New Deal framework.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“It will bring together MMT with climate action and indigenous rights interests.”

Good luck with persuading Australians to recognise indigenous rights.

New Zealand could be a beacon for you regarding indigenous rights, but I don’t think Australians would ever accept that particular resolution.

Richard Murphy has published his ideas for a Scottish Green new deal. All the while wanting to be at the heart of Europe and their growth and stability rules. It is hilarious that they think they would be able to do anything with 3% deficits. Of course rather than admit that they journey down a rabbit hole and say being half in and half out by joining up with Norway and Iceland etc. That Norway and Iceland will allow Scotland to introduce the large deficits it needs. They are delusional and live in a parallel universe to most MMT’rs.

It is quite a thing watching them trying to find as many rabbit holes as they can performing back flips and triple toe loops. Rather than just say there is no point to being a member of these so called free trade clubs that are packed with neoliberals. Just so you can hoard foreign currency at a central bank.

It is only a matter of time before these ballet dancers decide Scotland should use most of what skills and resources we have to make stuff for other countries to consume and pick an export to growth model. Pat themselves on the back for hoarding foreign currency they’ll never need.

Mike the editor of Bella Caledonia uses MMT economists however he sees fit. Like most of the Scottish think tanks.

He splashes MMT economists names across his website when it comes to the currency. When you challenge the fact of what you can do with 3% deficits and some fancy debt to GDP ratio number they bury their head in the sand and stick their arses in the air because of their love for Europe.

Why because Bella has no idea how Europe works apart from learning 15 Minute sound bites they hear from their TV sets.

A green new deal with 3% deficits makes the green parties in the UK sound more crazy then the raging liberals. That takes some doing. The green party must be infested with liberals just as much as the other parties are.

Bill,

I think you are overstating the relevance of equity speculation to long term investment.

A clear distinction has to be made between investors and the companies which actually do the investing.

Most companies take the long term view. They cannot make massive investment decisions otherwise. Their only concern is how best to raise the equity and debt finance to fund their investments. To some extent they have to be cognizant of stock market cycles and moods. However, any sound investment will find the finance, the only issue is how it will be priced and whether the investing company can tolerate the price of finance offered.

It seems to me private investment can proceed irrespective of how the mood of the stock market is at any point. Although, if the mood is particularly dark, raising capital may have to be deferred to a more propitious period.

Speculation is what it is. The main problem with speculation is how it is financed and what the stability implications might be.

Whilst there is a cohort of fast moving speculators there is also a larger cohort of long term investors.

Good start, using Keynes’ insights regarding the imperfections embedded in financial markets. As a former stockbroker I understood I was dealing with client savings. Continuous buying and selling savings assets was what I called ‘swapping spit.’ Keynes ‘Essays in Persuasion,’ has been called one of the best examples of applied economics.

“My role, as an academic, is to work through things and lay out blueprints to guide directions of activity based on that thinking. …But, moreover, I do see them as being guides for campaigning strategies, which can then be implemented by those who know more about those things than I ever will.” I understand Bill’s distinction between those who analyze and envision and those who work to turn those analyses and visions into reality. Repeatedly in this era of hyper-specialization, such distinctions are made by academics and by journalists, who choose to define their roles, for a variety of reasons, good and bad, as observers rather than actors. But I think that Bill sells himself short here, as do many other “observers,” because there is, at least for me, an inherent impulse to action in works such as “Reclaiming the State,” as much of an impulse to action as can be found, for example, in the parables of Jesus about the coming of the Kingdom of God, or in the Enlightenment rhetoric of Thomas Paine, or in the Communist Manifesto. As Bill implies, without such “blueprints” there can be no common direction for social action, and their value lies not only in instruction but equally in inspiration. Bill hates to blow his own horn, but there is a definite sound, loud and clear, which emanates from his continual meetings with politicians, public figures, and public-minded citizens, a sound which also comes through, often in more muted tones, on this blog. And that sound is indeed a call, an impetus, even a demand, for action. What was said of Paine could be said of Bill and others who promote MMT in conjunction with an admittedly meta-economic set of values. “Had Paine not drawn his pen, Washington would not have drawn his sword.” Thus the distinction between envisioning and acting can turn out to be vanishingly thin, they being, in situations like this, essentially, inescapably, of one piece.

I want to complain about the unproductive financial markets also. But then I start to think that maybe I am writing this comment on a device that might not have been produced without them. And that while I write, I am sitting in a house that wouldn’t have been built without them. A house that I definitely wouldn’t ‘own’ without finance. And so it becomes difficult to complain because it can be difficult to separate the parts that are unproductive from those that are somewhat productive.

Totally unrelated question- where did the anti-spam question that I had to answer before commenting go? I kind of miss it since it was really boosting my weekend quiz answer ‘correctness’ percentage. At least the way I was figuring them…

Hank. “Most companies take the long term view. They cannot make massive investment decisions otherwise.” Yea, right. That’s what Wall Street, Credit Raters, developers, were doing in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007. And Greenspan to boot. Prudent investing and sober judgement stood strong against greedy speculation! Why do you spew out nonsense like this when so recent a history proves it a lie.

Bill plays an exemplary role in what an academic should be, that is connecting with people and groups in society to effect progressive social change. There are very few that do this. Most are content pursuing their hobby in academia, or far worse, especially in economics, justifying the interests and greed of our elites. He is also an excellent and important public educator.

His writings have been very helpful for me in determining the positions to take regarding funding and taxation in the campaign I have been involved in to add drug coverage to publicly funded doctor and hospital services in Canada. It is often difficult to see one’s way when all political parties are neoliberal to a considerable extent. The clear strong positions the organisation I work with has taken have helped important allies to see where to go as well. Sadly full-on functional finance has not been possible but we have been able to call for funding with no new taxes.

The spectre of tax increases is the tactic used by opponents who say taxes will need to increase and we already pay too much tax. They ignore the huge cost savings that will occur via single payer negotiations and evaluation of the effectiveness of drugs. With respect to taxation levels I in fact agree our taxes are too high for the services we receive. This reality lends credence to the conservative ”taxes are too high” argument but good luck trying to convince ”social democratic” allies that we need more deficit spending. For many it seems taxation is the moral thing to do regardless of whether it is needed or not.

Great article.

Learned a lot today.

I have always wondered about winners and losers — some people will lose out because i win. I have always felt somewhat bad about the game of musical chairs. Its great to see that I have been thinking like Keynes for many years since i was a child.

Of course, the job is to lift everyone up.

” But then I start to think that maybe I am writing this comment on a device that might not have been produced without them. And that while I write, I am sitting in a house that wouldn’t have been built without them. A house that I definitely wouldn’t ‘own’ without finance. And so it becomes difficult to complain because it can be difficult to separate the parts that are unproductive from those that are somewhat productive.” Jerry Brown

Surely it’s a fallacy to think that ethical finance would produce less sustainable prosperity than our current system of government-privileged usury cartels?

But what is ethical finance? Surely not a return to needlessly expensive fiat (the Gold Standard) nor to increase privileges (See Warren Mosler’s proposals) for the banks in an attempt to make a corrupt system more stable.

Instead, for instance, if interest rates become too high why not lower them via equal fiat distributions to all citizens? Financed in part with negative interest on large and non-individual-citizen accounts at the Central Bank and on other inherently risk-free sovereign debt?

Yok,

“Wall Street, Credit Raters, developers,” are not the sort of organizations I am referring to.

You obviously didn’t get the distinction I am making between investors and business – they are entirely different animals. I suggest you think about this some more. And not all investors are of the ilk that were at the centre of the 2008 collapse.

I would suggest your vehement prejudice gets in the way of being rational.

I understand why you feel the way you do about the egregious behaviour of certain groups in the lead up to the 2008 financial disaster – I feel the same way.

Come on Andrew- stop calling me Shirley.

Yeah, I know it was a stupid movie and the joke doesn’t work well in writing.

Personally, I am all in favor of the central bank (or anyone else) giving me money.

@ Henry Rech:-

“Whilst there is a cohort of fast moving speculators there is also a larger cohort of long term investors” SEEMS plausible enough as a generalisation. What makes it dubious, however, is that it completely leaves out of account fluctuation in the relative sizes of the two cohorts over time.

I don’t know the figures (perhaps you do?) but surely the most significant change over the last several decades *must* be that the former cohort has grown – dramatically – whilst the latter has shrunk commensurately?

Or are you implying that that has no relevance?

Jerry Brown wrote:-

“And so it becomes difficult to complain because it can be difficult to separate the parts that are unproductive from those that are somewhat productive”.

I couldn’t disagree more.

I think it’s childishly easy to distinguish between betting in a casino in the hope of getting personally as rich as possible whilst adding precisely zero to the wealth or wellbeing of the community, and investing one’s savings in activities which give one a reasonable return whilst also not being societally destructive.

I’m surprised you say you can’t. Perhaps you lamented the demise of Lehmann Brothers…? Or are an admirer of the depredations of Goldman Sachs…?

If Wall Street and the City of London fell into gigantic sink-holes tomorrow, never to be seen again, the world would be a better place IMO. And there would still be plenty of willing investors in productive enterprises the following day.

Do you read Michael Hudson?

Ultimately, total markets deliver the winner-takes-all system that the misanthropic fathers of neoliberalism wanted all along. Hyperfinancialization in a fiat currency system only accelerates the process of wealth concentration at the expense of its stability due to the overblown speculative element. As Bill’s graphs show, the “real” economy (real gdp growth) remains largely unaffected by the gambling. That is until it is forced to pay the gamblers debts. Any “trickle-down” and “rising tides for all boats” talk is mere propaganda (amplified by the mass of clueless “classic” liberals) so the many tolerate the rule by the few.

I find the famous phrase attributed to Thucydides best describes the neoliberal (and imperial) mindset:

“For ourselves, we shall not trouble you with specious pretences … since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

The only difference being the reluctance to stop “troubling us with specious pretences” of the likes I mentioned before.

Hi Robert. Yes I have read some of what Michael Hudson has written and am somewhat familiar with his arguments. But am not an expert on that.

No- I am not an admirer of Goldman Sachs. As for Lehman… well I lament the deep recession that occurred around the time of that company’s demise. Affected my life and work and income significantly. But also led to me learning about MMT.

I would note that the world did not seem to change for the better after September 11, 2001 and therefore am not optimistic about your sink-holes ideas for the rest of Wall Street and London.

“and investing one’s savings in activities which give one a reasonable return whilst also not being societally destructive.” robertH

That’s the “loan-able funds” model and if only it were true!

Instead, “Bank loans create bank deposits” and, due to government privilege such as deposit insurance, banks are able to “safely” create vastly more deposits than they otherwise could.

So while we could and should have a largely loan-able funds finance model, government privileges for depository institutions, aka “the banks”, preclude this.

@ Andrew Anderson wrote:-

“That’s the “loan-able funds” model …”

It’s nothing of the kind!

Whatever causes you to make such a bizarre association?

The loanable funds model postulates that banks can only loan out what they take in in deposits/investments – ie no fractional reserve banking.

@robertH,

My point is that the honest saving and lending of EXISTING funds cannot compete with the ability of a government-privileged usury cartel to CREATE deposits as they lend (“Bank loans create bank deposits”).

Of course, even entirely private banks with entirely voluntary depositors might safely create SOME deposits but it’s government privilege such as deposit insurance that enables banks to create vastly more deposits than they otherwise could and expect to get away with it.

robertH,

“I don’t know the figures (perhaps you do?) but surely the most significant change over the last several decades *must* be that the former cohort has grown – dramatically – whilst the latter has shrunk commensurately?”

I don’t have figures but what you say is probably partly correct. I would not say that the cohort of long term investors has shrunk. If it had, the capitalist system would be in deep crisis. I don’t see it that way.

The shenanigans on Wall St., I would argue, are pretty much irrelevant to capital formation. Business gets to raise the capital it needs.

The problem with the shenanigans on Wall St emerge from how speculative activity is financed and the implications that has for the stability of the financial system.

Henry Rech wrote:-

“I would not say that the cohort of long term investors has shrunk. If it had, the capitalist system would be in deep crisis. I don’t see it that way”.

So what this boils-down to is a question of individual perception.

Many people, I would suggest, do precisely see it that way. Whose perception is right – yours or theirs (I would count myself among them BTW)?

I don’t of course aspire to change yours. The way I see it is that the trajectory of the modern capitalist system as it has developed over the past three centuries or so has been the normal one of most systems:- from inception – successful (largely) transition away from the former dispensation (perceived as “improvement”); throughout its mature phase – unstoppable hegemony, but punctuated by wars and severe crises each followed by restoration of “normality”, but at an increasingly frenetic tempo; in decline – its earlier virtues and values perverted, corrupted and despised, power suborned and captured by oligarchy/plutocracy, resorting increasingly to military adventurism to shore itself up against the inevitable. oncoming, collapse of the whole edifice – to be supplanted in its turn by the next dispensation (whatever that turns out to be).

I would say we are most definitely (and demonstrably) well into the final phase. But I appreciate that the death of capitalism has been predicted many times before, and each time the prophecy has turned out to be wrong – so far.

robertH,

Capitalism might be in crisis in the way you explain, but I would say it is not in crisis specifically because of stock market speculation.

I also believe that we would all be much better off if Wall Street and ‘The City’ fell into a hole.

They are not just a casino but are indeed blood sucking squids latched onto the face of humanity. They build speculative bubbles that misallocate capital and seriously harm entire nations when the markets crash. The more devious ones like Goldman Sachs profit from the crash as well as when the bubble inflates. They have made one of life’s necessities a dwelling, unaffordable to buy and even to rent for much of the general population in many of the world’s major cities. They have been the main drivers of the whole neoliberal disaster and all the misery that has caused. They are the main drivers of extreme wealth inequality. Their money and power has hijacked our governments, political parties, the civil service and parts of academia and are leading us all to Armageddon. Militarised police, kangaroo courts initially just for the poor but now for the average citizen and horrible jails for profit have been created by a co-opted state to make the greedy feel more secure from the 98 or 99%.

The financial elites even harm the world’s geopolitical balance as the old democracies are driven into decay and a mercantilist, predatory and more competent China gains the ascendency. The serious business of national defence has also become in the main a crony capitalist financial scam for unearned profit. Wars are even initiated for profit.

Predatory or vulture capitalism, crony capitalism, speculation, price gouging, massive hidden fees, fraud, tax evasion, excessively open markets, rampant environmental destruction and the rest have been driven largely by the parasites of the world of finance – and we don’t need them.

As previously mentioned, if there is a good productive investment proposal with acceptable risk then an investor will, or should, be found.

May the commercial banks return to the boring traditional core functions. May each nation have a large state owned bank to provide some more ethical competition and as a safe haven for customers of failed commercial banks. Insolvent commercial banks must not be rescued by the state and must be left to face the consequences of their actions. Proper regulatory oversight is mandatory. Social support must only be for citizens.

May our governments and parliaments fulfil their democratic mandate and act to create a better world for the general population as well as for the often abused creatures and natural environments we share our planet with.

The top 1% are dangerous and must be constrained by whatever means necessary to not harming the general population or our environmental sustainability. Dig a deeper hole if necessary.

I am familiar with comment sections on internet blogs and am not unused to the criticisms I often receive. I imagine pretty much every MMT advocate encounters these often if they comment on ‘mainstream’ economic forums.

But I am really kind of more upset with the criticisms I got here for my earlier comment that basically said that sometimes it might be difficult to distinguish the productive aspects of finance from the unproductive. Now Bill Mitchell, as he has done quite a few times before, explained some of how to distinguish these in a subsequent post. And I thank him for that.

But some of the rest of you really need to up your game, or take a chill pill, or really just figure something else out. And definitely find some other way than advocating the destruction of cities, or parts of them, if what you really want to do is regulate aspects of finance.