In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Japan is different, right? Wrong! Fiscal policy works

Japan is different, right? Japan has a different culture, right? Japan has sustained low unemployment, low inflation, low interest rates, high public deficits and high gross public debt for 25 years, but that is cultural, right? Even the mainstream media is starting to see through the Japan is different narrative as we will see. Yesterday (August 14, 2017), the Cabinet Office in Japan published the preliminary – Quarterly Estimates of GDP – which showed that the Japanese economy is growing strongly and has just posted the 9th quarter of positive annual real GDP growth. Private consumption and investment is strong, the public sector continues to underpin growth with fiscal deficits and real wages are growing. The Eurozone should send a delegation to Tokyo but then all they would learn is that a currency-issuing government that doesn’t fall into the austerity obsession promoted by many economists (including those in the European Commission) can oversee strong growth and low unemployment. Simple really. The Japan experience is interesting because it demonstrates how the reversal in fiscal policy can have significant negative and positive effects in a fairly short time span, whereas monetary policy is much less effective in influencing expenditure.

The UK Guardian article (August 15, 2017) – Japanese economy posts longest expansion in more than a decade – reported that:

Japan’s economy expanded at the fastest pace for more than two years in the three months to June, with domestic spending accelerating as the country prepares for the 2020 Toyko Olympics and low levels of unemployment encouraged businesses to invest …

The overall result was much stronger than expected by the market …

I presume that will mean the UK Guardian will refrain henceforth from publishing articles from economists or their own journalists that suggest that fiscal policy is ineffective, Japan is about to go bankrupt, Japan is about to hyper-inflate, or any other stupid claim that has been rehearsed since the early 1990s by mainstream commentators and which the likes of the Guardian have given oxygen.

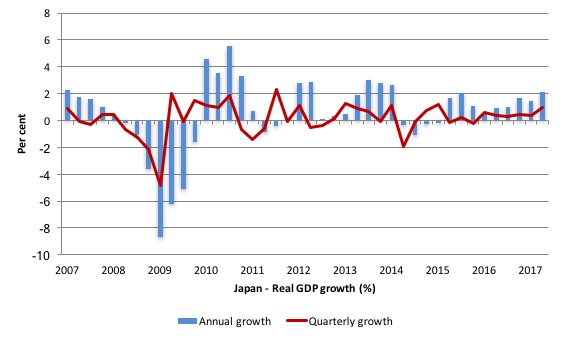

The following graph shows the growth of real GDP from the March-quarter 2007 to the June-quarter 2017. The annual growth (year-on-year) is in blue bars while the red line is the quarterly growth rate.

On an annual basis, Japan recorded an annual growth rate of 2.1 per cent in the June-quarter, the 9th quarter that annual growth has been positive.

The ‘sales tax’ recession of 2014 result, which was the direct outcome of neo-liberal incompetence is now well and truly behind it.

The quarterly growth rate was 1.0 per cent up from 0.4 in the March-quarter.

This is a very strong result and a testament to the on-going effectiveness of fiscal policy.

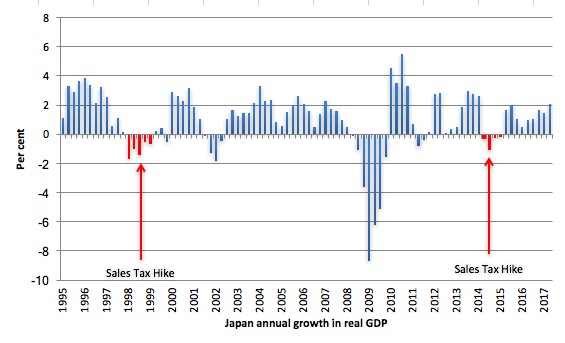

It is worth reminding ourselves of the folly of 2014 in Japan, which replicated the fiscal policy mistakes made in 1997.

In April 2014, the Abe government raised the sales tax from 5 per cent to 8 per cent.

After the sales tax hike, there was a sharp drop in private consumption spending as a direct result of the policy shift. At the time, I predicted it would get worse unless they changed tack.

It certainly did get worse. Consumers stopped spending and the impact of static consumption expenditure was that business investment then lags.

Here is the history of real GDP growth (annualised) since the March-quarter 1994 to the March-quarter 2015. The red areas denote sales tax driven recessions.

In both episodes, these recessions were followed by a renewed bout of fiscal stimulus (monetary policy was ‘loose’ throughout). In both episodes, there was a rapid return to sustained growth as a result of the fiscal boost.

Nothing could be clearer.

I provided detailed analysis of these historical shifts in these blogs:

1. Japan returns to 1997 – idiocy rules!.

2. Japan’s growth slows under tax hikes but the OECD want more.

3. Japan – signs of growth but grey clouds remain.

4. Japan thinks it is Greece but cannot remember 1997.

You might wonder what happened in 2002? The recession that occurred then in Japan was largely driven by an export collapse (remember the US went into recession during this period) and a tightening of net public spending. This then provoked a fall in private investment spending and a rising saving rate. It had nothing to do with the ratings decision.

Once exports recovered and public spending support resumed the economy then grew relatively strongly despite the lower sovereign debt ratings.

And then the 2007 crisis arrived.

Consumption spending growing strongly

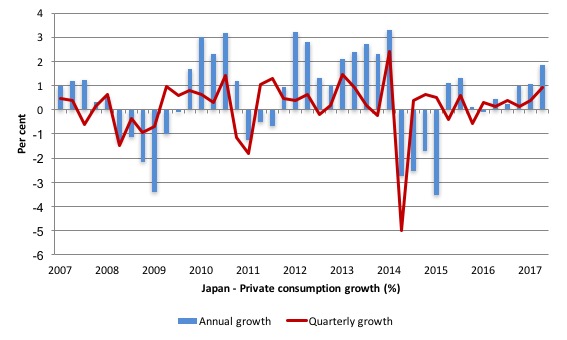

Private consumption spending grew at 0.9 per cent in the June-quarter 2017 and by 1.8 per cent in the previous twelve months.

The following graph shows growth in private consumption spending since the March-quarter 2007 to the June-quarter 2017. The blue bars are the annual (year-on-year) outcome, while the red line is the quarterly result.

This is one of those magnificent graphs that you show students to demonstrate intervention effects of government policy. Private consumption growth was growing fairly strongly on up to the beginning of 2014, after the impacts of the GFC and the Tsunami had been overcome.

The sales tax hike had the predictable negative effect and the quarterly growth of private consumption ever since was rather subdued until confidence returned.

In the last three quarters, that confidence appears to have returned and household consumption growth has been robust.

This has been helped by strong growth in wages.

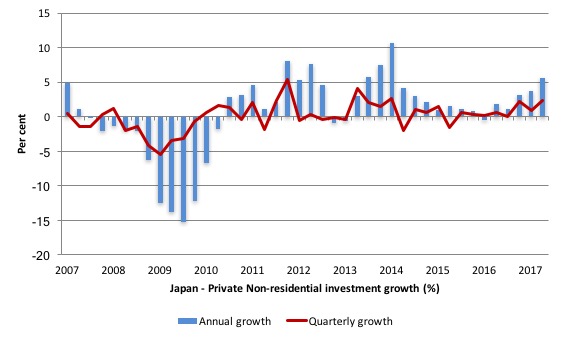

Investment spending growing strongly

With the stronger household consumption spending and the generally better economic outlook for Japan, private capital formation is now also contributing strongly to growth.

That is a message that is often forgotten. Fiscal stimulus boosts confidence, consumers start spending, sales increase, and firms a motivated to expand productive capacity – a virtuous cycle.

These boosts are in contrast to the mainstream macroeconomics, which consistently claims that the non-government sector will cut spending if the fiscal deficit rises. It is total nonsense, of course.

The following graph shows the annual growth in private investment from the March-quarter 2007 to the June-quarter 2017.

The outlook is bright.

Part of this boost in capital formation is due to the infrastructure being built in preparation for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. But the overwhelming influence is the brighter sales environment as consumers spend more freely.

Contributions to growth

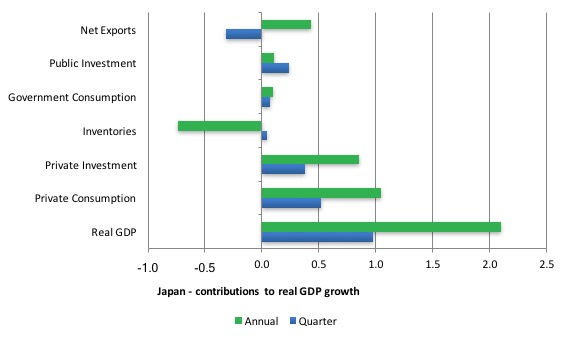

The next graph shows the contributions (in percentage points) to real GDP growth of the major expenditure categories in Japan over the last quarter and over the last 12 months (to the June-quarter 2017).

The annual results capture the impact of the introduction of the sales tax (April 2014) and its aftermath.

The major categories of expenditure that you would expect to be affected, either directly (private consumption) or indirectly (private investment) were negatively impacted.

It is also clear that over the last year, all the expenditure categories (public and private consumption, public and private capital formation, net exports) have contributed strongly to growth.

While net exports subtracted from growth in the June-quarter 2017, it boosted growth by 0.43 percentage points over the 12 month period.

The contribution of private consumption and investment is notable as is the sustained boost to growth from the public sector.

Consumer and Business Confidence

The Japanese Cabinet Office publishes a – Monthly survey of Consumer Confidence. The latest results, released on August 2, 2017 (for a survey conducted in July 2017) tells us:

1. “Consumer Confidence Index (seasonally adjusted series) in July 2017 was 43.8, up 0.5 points from the previous month.”.

2. All components that influence the Consumer Perception Indices were positive:

Overall livelihood: 42.3 (up 1.2 from the previous month)

Income growth: 41.7 (up 0.1 from the previous month)

Employment:48.1 (the same as the previous month)

Willingness to buy durable goods:43.2 (up 1.0 from the previous month)

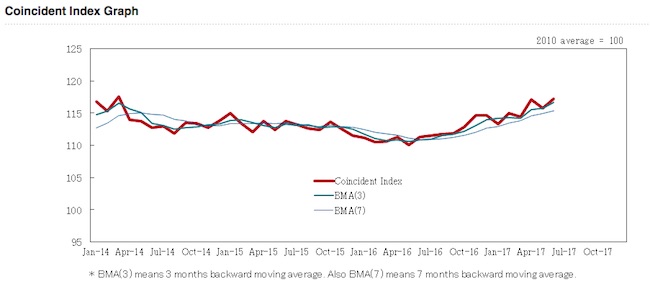

The Cabinet Office also publishes Monthly – Indexes of Business Conditions.

The latest result (August 7, 2017) showed that conditions were “Improving” in June 2017. The following graph is their latest time series (since January 2014).

Things have been looking up since mid 2016.

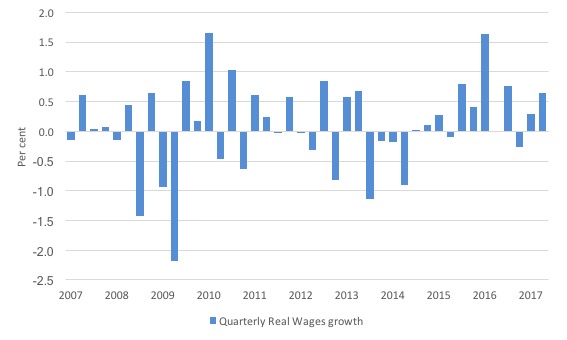

Real Wages growing steadily

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in real compensation for employees from the March-quarter 2007 to the June-quarter 2017.

With some exceptions, real purchasing power has been growing steadily since the sales tax disaster in 2014-15 was resolved with renewed fiscal expansion.

I note that recently more commentators are starting to appreciate that Japan demonstrates, categorically, that mainstream macroeconomic theory is bereft and has no credibility.

A recent Bloomberg article (August 3, 2017) – Japan Buries Our Most-Cherished Economic Ideas – concludes that:

Japan is the graveyard of economic theories. The country has had ultralow interest rates and run huge government deficits for decades, with no sign of the inflation that many economists assume would be the natural result.

The “theories” should, in fact, be singular – mainstream macroeconomic theory (particularly New Keynesian economics).

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has always been able to embrace the evidential base produced by Japan.

There is no surprise to an MMT economist that:

1. Japan has large fiscal deficits relative to other nations.

2. It has relatively large gross public debt.

3. Its bond yields have been low and stable for decades.

4. It has had close to zero interest rates for decades.

5. It has low inflation.

6. It has very low unemployment.

It all comes down to understanding how the monetary system operates and the recognising capacities that a currency-issuing national government has to use fiscal and monetary to advance well-being.

The Bloomberg article notes that:

Some economists think more fiscal deficits could help raise inflation. That’s consistent with a theory called the “fiscal theory of the price level,” or FTPL. But a quick look at Japan’s recent history should make us skeptical of that theory — even as government debt has steadily climbed, inflation has stumbled along at close to 0 percent …

The mainstream theory doesn’t understand that fiscal deficits are no more likely to cause inflation as growth in non-government spending should the capacity of the economy be able to absorb the extra nominal spending.

If it is not capable, then there is no need to expand the deficit because the economy would already be at full employment!

But the Bloomberg journalist (Noah Smith) can see that Japan kills off mainstream economic theory, as an academic economist he still wants to hang on to it.

He claims that:

There’s just one catch — government debt.

With long-term interest rates very low and tax receipts rising due to economic growth, Japan’s mountain of government debt isn’t as bad as it appears. The government can roll over long-term bonds at increasingly low interest rates until interest payments essentially vanish. But as long as that mountain of debt remains, Japan will be forced to keep interest rates low. This situation is known as “fiscal dominance,” and it means the central bank no longer has effective control over its own monetary policy. That’s not catastrophic, but it’s not optimal. Inflation, if it ever materialized, could help erode that debt.

Which tells you that he hasn’t understood much at all.

And the terminology – “mountain of government debt” – is telling.

First, Japan’s central government debt to GDP ratio is in net terms – once you take into account the fact that the Japanese government holds huge stockpiles of financial assets – around 90 per cent.

Second, the Bank of Japan holds a significant amount of government bonds. If these are taken out the debt ratio drops to around 45 per cent

Hardly a mountain. But then who cares if the numbers were higher than this anyway? No-one should.

Japan can always meet its yen-denominated liabilities, irrespective of the interest rates. The only difference is that with low interest rates, the fiscal space is larger for non-interest payment spending.

Conclusion

The latest national accounts data continues to teach us lessons about monetary and fiscal policy.

We learn from the sales tax debacles and the most recent data that:

1. Fiscal policy works in both directions – trying to cut deficits when the economy is below full employment will reduce economic growth (and vice versa).

2. Monetary policy does little to stimulate real spending in a monetary economy and can not offset contractionary movements in fiscal policy. The Bank of Japan has been engaging in more quantitative easing and interest rates remain around zero – but there has so far been very little real GDP impact.

Crowdfunding Request – Economics for a progressive agenda

Only 13 days left and 53 per cent of the target achieved.

I received a request to promote this Crowdfunding effort. I note that I will receive a portion of the funds raised in the form of reimbursement of some travel expenses. I have waived my usual speaking fees and some other expenses to help this group out.

The Crowdfunding Site is for an – Economics for a progressive agenda.

As the site notes:

Professor Bill Mitchell, a leading proponent of Modern Monetary Theory, has agreed to be our speaker at a fringe meeting to be held during Labour Conference Week in Brighton in September 2017.

The meeting is being organised independently by a small group of Labour members whose goal is to start a conversation about reframing our understanding of economics to match a progressive political agenda. Our funds are limited and so we are seeking to raise money to cover the travel and other costs associated with the event. Your donations and support would be really appreciated.

For those interested in joining us the meeting will be held on Monday 25th September between 2 and 5pm and the venue is The Brighthelm Centre, North Road, Brighton, BN1 1YD. All are welcome and you don’t have to be a member of the Labour party to attend.

It will be great to see as many people in Brighton as possible.

Please give generously to ensure the organisers are not out of pocket.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It seems like if the whole world adopted the Japanese solution, we can see the continuation of Capitalism without any problems forever?

Great article as always but I was hoping for and disappointed that Japan’s large current account was not discussed here.

Given the core MMT argument that imports are a benefit – one could certainly apply to the USA and UK, given their large current account deficits – Japan is the opposite.

Now, you just created a post on the negatives on Germany’s current account surplus, the suppression of domestic demand and focused on the growing outcome of the lack of public infrastructure investment there. Of course, a major different between Germany and Japan (apart from the Eurozone ) is that Germany runs a government surplus mostly.

Still what are the negatives of Japan’s current account surplus? What are the negatives of the huge financial injection into private domestic sector? After all if imports are a benfit then export are a cost. Are there any that are specific to Japan?

Without addressing this, it leaves open the possibility that other arguments could be made that “Japan is different” due to its current account surpluses.

Hello,

Great Blog post. Thanks.

In one applies some sectoral flow theory to the Japanese headline numbers one finds some considerable strength.

GDP = Private Sector [P}+ Government Sector[G] + External Sector[X]

When we take our inputs and place them in our formula, we can calculate the following sectoral flow result based as a percentage of GDP. The numbers in absolute terms are growing because GDP is increasing.

2016

P G X P+G+X

2.2%+4.5% +3.7%=10.4%

NOW

3%+4.3% +3.7%=11%

This is the sectoral flow as a percentage of GDP, not GDP for the year.

Bill, I would love to say that you may well be right about the Guardian re macroecon nonsense, but I can’t. They may cease saying these things about Japan, but it probably won’t stop them doing so about the UK. Just today, Aditya Chakrabortty published an article about what is taking place in the UK ten years after the crash. Near the end, he plunges headlong into the gaping jaws of the neoliberal mantra. Here is what he writes:

“According to the Bank for International Settlements [recent Annual Report], the UK is far deeper in the red now than it was when Northern Rock collapsed. Government debt has shot up under the Conservatives, but so too has household borrowing. Were the UK to crash again, its government no longer has the political capital nor the fiscal headroom to save the financial system. And with interest rates scraping along the bottom, the Bank of England has barely any firepower left. Ten years of political fudge and failed austerity has left Britain’s state machinery tapped out.”

This passage is such a mish-mash of fact and fiction, it doesn’t seem to be worth parsing. While I like his political stances, this is an egregious economic error. Polly Toynbee made a similar error just the other day. She has made such errors before and does not seem to be able to learn from them. But then, she isn’t an economics editor like Chakrabortty. Upshot: I am pessimistic about whether the Guardian will be able to either learn from the Japanese experience or, if they are able to, able to transfer that understanding to the UK situation. [I know you didn’t mention the latter, but one would have hoped that if they could do the former, they could do the latter.]

Alan, I am sorry to say that your equation doesn’t make any sense. Have you included all the operators?

Alan, apologies, but I meant this bit:

P G X P+G+X.

It doesn’t make any sense to me.

It must be the hinge around which turns the ignorance of mainstream economic thought, Government debt!

Always it gets mentioned in the mainstream that government debt is a bad thing. This nonsense is simple proof that the writer/s are pretty clueless even about ordinary banking, let alone Macroeconomics. Every time I see it a red flag goes up. Japan must cop most of the “abuse”.

Alan,

I would set out the sectoral balance accounting identities as follows:

(S – I) = (G – T) – (X – M), which should yield

(S- I) – (G – T) + (X – M) = 0, where (S – I) is the private sector, (G – T) is the public sector (including government), and (X – M) the current account balance.

Re GDP, I have left out private expenditure, or consumption, say C. This leads me to define “GDP” as

GDP = C + I + G, where I is private sector investment, or expenditure, and G is government expenditure.

“GDP”, aggregate income, can be defined differently, yielding similar results in terms of the sectoral balances.

This enables me to straightforwardly contend that private sector surplus = government deficit.

I hope this makes sense as I have simplified things and, hopefully, haven’t made any errors.

Hello Larry,

Thanks for your reply.

Yes, you are right my entry contains a type which I cannot fix in the original post.

Should have been as follows:

GDP = P + G + X

The formula

(S – I) = (G – T) – (X – M) is what I used, simplifying it down to P for S-I, G for G-T and X for X-M.

Each one derives a flow number based on the official stats which one can get from trading economics dot com. Once one has done the sum one has one number left and can compute a total flow.

P = Credit creation from banks. – Banks lend more than is repaid in loans.

X = Externally from overseas commerce.- Exports bring in more than imports cost + capital flows.

G = Government spending. – More is spent than taxed.

The info should have looked like this:

“2016

P + G + X = GDP

2.2%+4.5% +3.7%=10.4%

NOW

3%+4.3% +3.7%=11%”

Though to my defense I did write this right at the beginning of my post:

GDP = Private Sector [P}+ Government Sector[G] + External Sector[X]

Thanks

Hi Alan,

I thought it might be a typo. I create them all the time. They are such a pain. Many thanks for your clarification. I thought we agreed but I wasn’t quite sure.

Martin, Bill did mention current accounts in the form of Japanese exports. He wrote the following:

“You might wonder what happened in 2002? The recession that occurred then in Japan was largely driven by an export collapse (remember the US went into recession during this period) and a tightening of net public spending. This then provoked a fall in private investment spending and a rising saving rate. It had nothing to do with the ratings decision.

Once exports recovered and public spending support resumed the economy then grew relatively strongly despite the lower sovereign debt ratings.”

You must have missed it. Easy to do.

Larry, Your criticism of the Guardian’s ability to say anything worthwhile on economics applies just as much to other papers. Simon Wren-Lewis (Oxford economics prof) has coined the term “macromedia” for the nonsense spouted by newspaper economics commentators.

But all is not lost: I saw an article the other day saying that journalists will to an increasing extent be replaced by computers in the future. So that might improve the quality of newspaper articles. Or perhaps that article itself was nonsense….:-)

@larry

I generally like Chakrabortty, and his heart’s in the right place, but I gave up after the first few paragraphs of his article today, when I read this:

“Here’s the stuff of historical bad dreams: at the height of the banking crisis in 2008, every man, woman and child in Britain handed over £19,721 each to bankers.”

Yes, the bankers did a reverse bank-robbery alright, and have taken the piss ever since, but I certainly never gave them £19,721!

The bank bailouts were paid with the Government’s money, not with ours.

If he doesn’t know the difference then he’ll never understand how the economy works.

Bill,

Do you have any plans to write any articles on the Chinese economy? I would be most interested, especially in light of the recent warning from the IMF about the level of debt China currently has.

Many thanks.

C

“Simon Wren-Lewis (Oxford economics prof) has coined the term “macromedia” for the nonsense spouted by newspaper economics commentators.”

And let’s face it, when it comes to emitting nonsense Simon is definitely an expert.

I’m afraid that is all part of Simon’s “Everybody other than me and my mates is talking nonsense” framing trick.

And Neil, we mustn’t forget that W-R and his mates train the leaders of the nation. He told us so.

Great blog post.

The only worrisome thing is that when I was in Japan this summer, newspapers wrote about Abe’s intention to increase the sales tax to 10 percent, and “reduce public debt”, so we’ll see whether the Japanese government itself has learned their lesson.

And of course he’s trying to use the positive economic climate to get rid of pacifism in the constitution.

@Dave Kelley: well, we’d still have a resource-overconsumption problem, as well as one of overpollution.