Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

The rise of non-standard work undermines growth and increases inequality

One of the on-going themes that emerges from the neo-liberal commentariat is that fiscal deficits undermine the future of our children and their children because of the alleged higher implied tax burdens. The theme is without foundation given that each generation can choose its own tax structure, deficits are never paid back, and public spending can build essential long-lived infrastructure, which provides benefits that span many generations. The provision of a first-class public education system feeding into stable, skilled job structures is the best thing that a government can do for the future generations. Sadly, government policy is undermining the future generations but not in the way the neo-liberals would have us believe. One of my on-going themes is the the impact of entrenched youth unemployment, precarious work and degraded public infrastructure on the well-being and future prospects of society as neo-liberal austerity becomes the norm. This theme was reflected (if unintentionally) in a new report, release last week by the OECD – In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. The Report brings together a number of research findings and empirical facts that we all knew about but are stark when presented in one document.

The full document can be read on-line (link above) and the OECD provided – Chapter 1 Overview of inequality trends, key findings and policy directions – for free download.

What we learn is that:

Over the past three decades, income inequality has risen in most OECD countries, reaching in some cases historical highs …

There are two concepts of – income distribution – that economists consider.

First, the so-called size distribution of income or personal income distribution, which focuses on distribution of income across households or individuals. Often the data is expressed in percentiles (each 1 per cent from bottom to top), deciles (ten groups each representing 10 per cent of the total income), quintiles (five groups each representing 20 per cent of the total income) or quartiles (self-explanatory).

Various summary measures are used to demonstrate the income inequality. For example, the share of the top 10 per cent to the bottom 10 per cent.

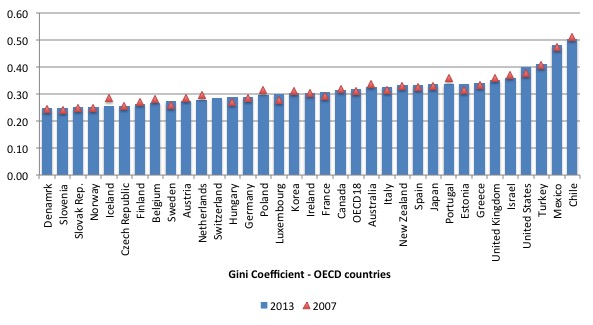

The Gini coefficient is another summary measure used in this type of analysis. The Gini Coefficient takes the value of zero when everyone in the income distribution has the same income and at the other extreme a value of 1 where one person has all the income. So rising values indicate increased inequality.

Second, the functional distribution of income or the factor shares approach, which divides national income up by what economists call the broad claimants on production – the so-called “factors of production” – labour, capital, and rent. Other classifications also include government given it stakes a claim on production when it taxes and provides subsidies (a negative claim).

As I have recently noted, the shift in most nations has been towards profits gaining a greater share of national income at the expense of wages. Please read my blog – Neo-liberal dynamics restored after the shock of the GFC – for more discussion on this point.

This academic article (from 1954) – Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning – is a good starting point for understanding the two concepts in more detail, although you need a JSTOR library subscription to access it.

[Full Reference: G. Garvy (1954) ‘Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning’, The American Economic Review, 44(2), Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1954), 236-253].

The OECD Report is about rising income inequality in the distribution of personal income rather than how national income is divided between the broad classes (for example, wages and profits).

The first graph taken from the OECD’s – Latest data on inequality and poverty – shows the Gini coefficient for 2013 or the most recent value (blue bars) and the value in 2007 (red triangles).

In most cases, inequality has risen over the period since the GFC and its aftermath.

The other measures focus on the percentile distribution (bottom 10 per cent, top 1 per cent etc) get of total distributed income. The OECD say that:

In the United States and other advanced economies … the richest 1% and, increasingly, the 0.1%, the groups that have enjoyed the lion’s share of income growth in recent decades … The rise of “the super-rich” has led to warnings about the risks of rent-seeking and political and economic “capture” by the economic elite.

But … focusing on them exclusively risks obscuring another area of growing concern in inequality – namely the declining situation of low-income households. This is not a small group. In recent decades, as much as 40% of the population at the lower end of the distribution has benefited little from economic growth in many countries. In some cases, low earners have even seen their incomes fall in real terms … When such a large group in the population gains so little from economic growth, the social fabric frays and trust in institutions is weakened.

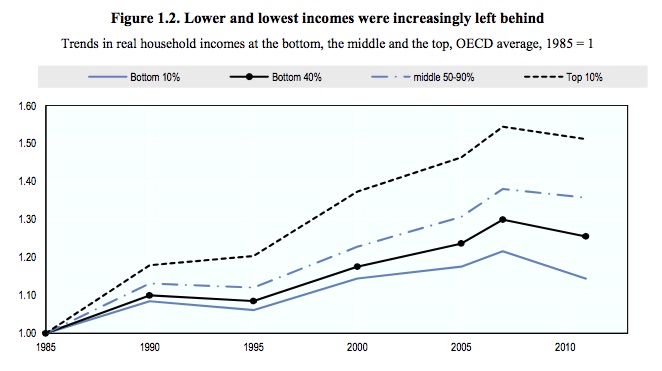

The OECD produced the following graph (their Figure 1.2) which traces the real household income across various percentile groups for the average OECD outcome.

You can see that income inequality was rising before the GFC and has worsened over the last several years.

The OECD claim that inequality:

… is so deeply embedded in our economic structures, it will be hard to reverse it.

They fail to acknowledge that these trends in our “economic structures” have been in some cases, deliberately created by government policy aimed at satisfying the demands of the elites for a greater share of national income.

The sort of things I emphasise are the maintenance of entrenched unemployment, the casualisation of the labour market via the retrenchment of job protection rules and other legislative changes, the related rise of underemployment as firms have rationed the shortage of total spending in the economy into shorter hour jobs.

The OECD likes to emphasise technological change and globalisation as if they are too big for policy to confront and beyond the scope of any one nation to deal with.

But any government that issues its own currency can guarantee full employment and decent pay irrespective of what the global forces of capital deem to be in their best interests.

The OECD bias is seen in their claim that:

One of the messages of this report is that structural policies are needed now more than ever to put our economies back on a path of strong and sustainable growth, but have to be carefully designed and complemented by measures that promote a better distribution of the growth dividends.

If you recall my recent blog – Demand and supply interdependence – stimulus wins, austerity fails – you will have learned that one has to tread very carefully when talking about structural policies independent of the state of the economic cycle.

More reasonable economists understand that the division between so-called structural and cyclical outcomes is fraught because the state of the cycle can introduce structural imbalances, which are reversible once the cycle turns back again.

The example often given is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved.

A number of non-wage labour market adjustments accompany a low-pressure economy – training opportunities provided with entry-level jobs decline as vacancies fall; redundant workers face skill obsolescence.

In a recession, many firms disappear all together, particularly those who were using very dated capital equipment that was less productive and hence subject to higher unit costs than the best practice technology.

But just as the downturn generates skill losses, a growing economy stimulates the provision of training opportunities as the unemployment queue diminishes. This is one of the reasons that economists believe it is important for the government to stimulate economic growth when a recession is looming to ensure that the skill transitions can occur more easily.

By stimulating output growth now, governments also help relieve longer-term constraints on growth – investment is encouraged and workers become more mobile.

The OECD is a major neo-liberal institution and maintains the myth that growth can occur in times of austerity if so-called structural reforms are introduced. We only have to examine the way the Greek economy is performing to invalidate that proposition.

Structural adjustments do result in lower production costs as high cost firms exit and new capital is introduced. That sort of process occurs in the growth spurt after a recession if the government is supporting spending while private spending remains fragile.

It doesn’t easily happen when an economy is mired in recession for years on end.

An interesting aspect of the Report is that the OECD has joined the IMF in finally admitting that “higher inequality drags down economic growth”. No more trickle down from them.

Please read my recent blog – Trickle down economics – the evidence is damning – for more discussion on this point.

They present “new evidence”:

… that the long-term rise in inequality of disposable incomes observed in most OECD countries has indeed put a significant brake on long- term growth. Further, it shows that efforts to reduce inequality through redistribution – typically, certain forms of taxes and benefits – do not lead to slower growth … This suggests that redistribution can be part of the solution, but requires a serious discussion on how to promote effective and well-targeted measures that promote a better sharing of the growth outcomes not only for social but also for economic considerations.

The IMF came to a similar view in a 2011 paper. Please read my blog – Rising inequality demonstrates we haven’t learned much – for more discussion on this point.

We conclude from their paper that a prerequisite for resolving the unsustainable imbalances that led to the financial crisis will be to dramatically redistribute income back to workers – so that real wages growth closely tracks productivity growth and workers in sectors with little union representation are able to similarly participate in national productivity gains.

The OECD note that some of the poorer nations have been able to combine growth stimulus with “well-targeted social and employment programmes” that reduce income inequality. One example they provide is the Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados in Argentina or the Head of Households job guarantee.

I discussed the Jefes program in these 2012 blogs – A Greek exit would not cause havoc and Employment guarantees should be unconditional and demand-driven.

At the time of the 2001 crisis, the Argentinean government realised it had to adopt a domestically-oriented growth strategy. One of the first policy initiatives taken by newly elected President Kirchner was a massive job creation program that guaranteed employment for poor heads of households.

Within four months, the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar (Head of Households Plan) had created jobs for 2 million participants which was around 13 per cent of the labour force. This not only helped to quell social unrest by providing income to Argentina’s poorest families, but it also put the economy on the road to recovery.

A key Argentine government official (advising the Minister of Employment) who was instrumental in the implementation of the Head of Households Plan had earlier attended a Conference in Chicago in 1998 and attended a session where Randy Wray and myself presented papers outlining the way in which a Job Guarantee would operate and provide macroeconomic stability. We have stayed in touch ever since.

Conservative estimates of the multiplier effect of the increased spending by Jefes workers are that it added a boost of more than 2.5 per cent of GDP. In addition, the program provided needed services and new public infrastructure that encouraged additional private sector spending. Without the flexibility provided by a sovereign, floating, currency, the government would not have been able to promise such a job guarantee.

Argentina demonstrated something that the World’s financial masters didn’t want anyone to know about. That a country with huge foreign debt obligations can default successfully and enjoy renewed fortune based on domestic employment growth strategies and more inclusive welfare policies without an IMF austerity program being needed.

The clear lesson is that sovereign governments are not necessarily at the hostage of global financial markets. They can steer a strong recovery path based on domestically-orientated policies – such as the introduction of a Job Guarantee, which directly benefit the population by insulating the most disadvantaged workers from the devastation that recession brings.

And you should note – the Jefes was a cyclical rather than a structural policy. The Job Guarantee I advocate would be an embedded automatic stabiliser that dampened the impacts of a collapse in private spending.

So a reasonable reader would ask as they trawled through this latest OECD report – why do they continue to claim that sustainable growth will require ‘structural reform’, by which they mean microeconomic policy changes (typically abandonment of job protections, wage cuts, income support cuts for pensioners, deregulation of markets etc), when they point to the benefits of well-crafted public job creation programs, which are macroeconomic policy interventions.

How does inequality hinder growth?

The OECD consider that:

… the biggest factor for the impact of inequality on growth is the growing gap between lower income households and the rest of the population. This is true not just for the very lowest earners – the bottom 10% – but for a much broader swathe of low earners – the bottom 40%. Countering the negative effect of inequality on growth is thus not just about tackling poverty but about addressing low incomes more broadly.

They note that the problem emerges by “curbing opportunities for the poor and middle classses”. These opportunities include “investment in education … skills and employment”.

All of which have become more restricted by the sort of neo-liberal policies that the OECD itself championed under its 1994 Jobs Study reform agenda.

So it has been common for mainstream economists and policy makers to postulate that there is a formal link between unemployment persistence, on one hand and so-called “negative dependence duration” and long-term unemployment, on the other hand. Although negative dependence duration (which suggests that the long-term unemployed exhibit a lower re-employment probability than short-term jobless) is frequently asserted as an explanation for persistently high levels of unemployment, no formal link that is credible has ever been established.

However, despite the lack of evidence, the entire logic of the 1994 OECD Jobs Study which marked the beginning of the so-called supply-side agenda defined by active labour market programs was based on this idea.

The emphasis was on so-called ‘supply-side activation’ – a fancy word for blaming the victims of a spending (demand) failure and threatening them with penury should they not agree to submit to the pernicious management regime with so-called ‘case managers’. In Australia, this amounted to the unemployed being required to keep “dole diaries” to account for their time, record meetings with prospective employers etc. It also includes working for free.

Unemployment was conceived of being a matter of choice by those who had to allocate time between leisure and work and chose the former. It was claimed that income support payments (dole) subsidised that choice and if cut would force the workers back into work.

The empirical reality didn’t accord with the supply-side policy emphasis that OECD governments adopted in response to the release of the Jobs Study.

While the mainstream economics profession may claim search effectiveness declines and this contributes to rising unemployment rates, the overwhelming evidence is that both are caused by insufficient demand – not enough jobs. The policy response then is entirely different.

The unemployed cannot search for jobs that are not there. Please read my blogs – What causes mass unemployment? and – The unemployed cannot find jobs that are not there! – for more analysis of these issues.

Modern monetary theory (MMT) is clear – mass unemployment arises when the fiscal deficit is too low given the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector.

To reduce unemployment you have to increase aggregate demand (spending). If private spending growth declines then net public spending has to fill the gap. In engaging this debate, we also have to be careful about using experience in one sector to make generalisations about the overall macroeconomic outcomes that might accompany a policy change.

Targetted spending in public education, skills training (proper apprenticeships), public investment in new innovations in personal care services, renewable energy, public transport, etc are all likely to reduce inequality by opening up broader opportunities for those at the back of the unemployment queue.

The problem that arises when entrenched mass unemployment is maintained is that the employers get too much choice and can discriminate against those with less skills. When the labour market is tight (full employment) the employers have to mould their jobs to the available supply and construct appropriate training opportunities to ensure the worker fits the task.

That dynamic efficiency is lost when there is mass unemployment.

The government can force that dynamic to emerge by starving the private sector of workers. It can also adopt employment criteria that are more inclusive to those with disabilities, other difficulties etc and thus open up opportunities for career advancement for those normally cast aside by the private market.

Further, it can target new activity into environmentally friendly activities.

I note some commentators still lump me into the ‘growth at all costs’ school of thought. They are wrong. The point is that with an expanding population if all persons are to participate in the material wealth of the society there has to be economic growth in the way we measure it.

Otherwise, many people are going to live in material deprivation and I don’t see a major groundswell for those not in that state to sacrifice their comfort to lower the average standards of living around the World.

Further, there are many people living in wretched material states of deprivation.

The only solution is economic growth. The point is to be smart about it. There are many growth-inducing activities that have a small environmental footprint and many that actually enhance the healt of our natural systems. All should be targets of public sector job creation and spending – economic growth will result, less inequality will result, more people will be materially better off, and the Greens will be happy!

Back to the OECD Report.

The new element they introduce into their evolving awareness that their past emphasis on the supply side might be missing the point – although they don’t express it in this way – is the problem of temporary and part-time jobs in causing rising inequality.

They note that:

Promoting equality of opportunities is not just about improving access to quality education but also ensuring that the investment in human capital is rewarded through access to productive and rewarding jobs … the potential for this to happen has been undercut by the gradual decline of the traditional, permanent, nine-to-five job in favour of non-standard work – typically part-time and temporary work and self-employment. More (often low-skilled) people have been given access to the labour market but at the same time this has been associated with increased inequalities in wages and, unfortunately even in household income.

Which means that not only does the government need to ensure there are enough jobs but also that the quality of jobs increases.

The OECD trot out the usual ‘technological determinism’ argument that the “development of non-standard work is related to technological changes and the associated evolution of labour demand”.

Sure enough, technology has changed the nature of labour markets – I now type all my own papers etc meaning that the former secretarial function has gone – but that doesn’t mean lead to casualisation, precarious and low-paid work.

It frees workers to engage in other areas of activity.

It is claimed that technology has wiped out low skill jobs and a lack of education and training has then prevented those workers from being reengaged in higher skilled employment (such as IT etc).

But that only applies if we assume there are no lower skills jobs remaining to be done. I could design millions of such jobs which would advance human well-being, protect the environment and allow workers with lower levels of education to fully participate in meaningful work and earn a solid living.

The assembly-line factory jobs might have gone in many nations but there are millions of jobs available in personal care services, creative industries, environmental care, community development – and the list goes on.

The point is that private profit-making calculus won’t create those jobs. Which is why the public sector that has to satisfy different decision-making goals (well-being of society etc) should create them.

Even the OECD is sensible enough to say:

Since nearly all job losses, regardless of the type of task, were associated with regular work, while growth in employment took place mainly in the form of non-standard employment, technological advancement alone cannot be the only explanation for job polarisation. Labour market institutions and policies have also probably played a role …

Probably is the understatement.

The “spread of non-standard work” as the OECD puts it is largely due to the innovations of capital to reduce costs in a period of largely deficient aggregate spending – and I am not just talking about the GFC period here.

Many nations were already in the grip of austerity before the GFC hit – it was a slow-burning type of austerity. For example, the period when the prospective Eurozone nations were trying to meet the so-called convergence criteria (under the Stability and Growth Pact and the broader Euro rules regarding interest and inflation rates) was marked by elevated unemployment rates and tight fiscal positions.

In many advanced nations, full employment was abandoned thirty or more years ago in favour of entrenched mass unemployment and growing underemployment.

In this period, as trend economic growth in nations fell a step below previous trends, the employers took advantage of the slack conditions by fractionalising their employment structures.

The mainstream claim this was a supply-side initiative – married women entering the workforce and desiring part-time work to mix their family responsibilities – and employers just acted virtuously to meet that social preference.

If that was exclusively true then rising underemployment would not have occurred.

The OECD is correct, though, in highlighting the role that non-standard employment has played in rising inequality. They conclude that more than half of all jobs created since 1995 were non-standard jobs”.

While these jobs “are not necessarily bad jobs” they “can also be associated with precariousness and poorer labour conditions where non-standard workers are exempted from the same levels of employment protection, safeguards and fringe benefits enjoyed by colleagues on standard work contracts.”

The evidence is that “many non-standard workers are indeed worse off on a range of aspects of job quality”, which once again militates against the mainstream claim that these job changes were to suit “better work-family life balance, higher life satisfaction … a greater sense of control” for workers.

The OECD notes that:

1. “a non-standard job typically pays less than traditional permanent work”.

2. “temporary workers face substantial wage penalties, earnings instability and slower wage growth compared to permanent workers”.

3. “Non-standard workers suffer other penalties, too … less likely – to receive training … also face higher levels of insecurity in terms of the probability of job loss and unemployment and, in the case of temporary workers, report significantly higher job strain”.

4. “People are more likely to be poor or in the struggling bottom 40% of society if they have non-standard work, especially if they live in a household with other non- standard or non-employed workers”.

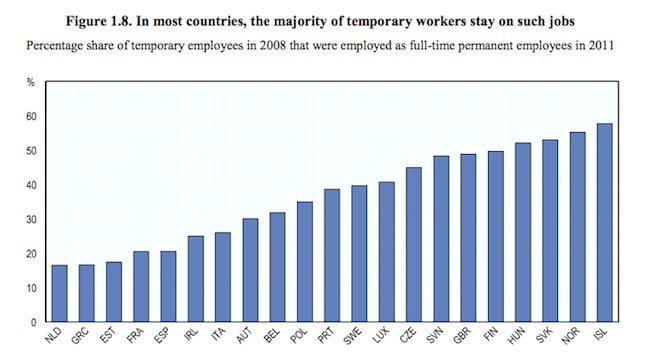

They also (finally) provide evidence to refute the so-called “stepping stone” hypothesis, which claims that casualised, low skill work is good for people because it allows then to transit into better paying jobs as a result of the extra work experience.

Some of the mainstream research used to substantiate the stepping stone argument does not exclude students who combine school/study and casual work. This biases the results in favour of the stepping stone argument. Why? Because students who engage in casual work to support them while studying and then upon graduation enter a professional occupation are not representative examples.

The successful transition from casual work to full-time work has nothing to do with the casual work experience. The casual work has nothing much to do with the skills they subsequently garner in their professional capacity which requires only a university qualification for entry. Further, the casual employment undertaken typically bears no relationship to the industry or occupation that they enter after finishing their studies.

I have written about this in the past. Please read my blog – Casual work traps workers into low-pay and precarious jobs – for more discussion on this point.

The evidence is overwhelming. Casual work traps workers into a life of precarious employment with low-pay.

The OECD is now acknowledging that. They produce this graphic headed “In most countries, the majority of temporary workers stay on such jobs”.

Conclusion

For an earlier analysis of the OECD’s emerging awareness of these issues, please read my blog – Trickle down economics – the evidence is damning.

The OECD correctly point out that:

There is nothing inevitable about growing inequalities. Policy makers have a range of instruments and tools at hand to tackle rising inequality and promote opportunities for all while also promoting growth.

The starting point is that all those who want to work (and can) should have a job which provides a pay level that permits the worker to operate in an inclusive way within society.

The dynamic for that has to come from a renewed committment by governments to act as an employer and a quality-setter which then forces private employers to lift their standards.

The government could wipe out underemployment by offering meaningful Job Guarantee jobs on a full-time (or desired part-time) basis to anyone who wanted them. The private employers would have to match conditions or go out of business. Win-Win.

Governments must ensure that minimum wages are adequate and workers have ample scope for holiday pay, sick pay, etc and are able to access further training and education. Private employers then have to follow suit. Again, the best vehicle is a comprehensive Job Guarantee which sets the benchmark upon which all other jobs are created.

All of which will require (most likely) higher fiscal deficits, a larger public sector involvement in the economy, more regulation and job protection, and that real wages grow in line with productivity growth.

In short, these changes require an abandonment of the neo-liberal policy dominance. That is how large the challenge is.

The OECD, of course, do not recognise that the required changes will not be possible within the current ideological framework that they help to perpetuate.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

On the contrary I do think capitalistic countries can create “bullshit jobs” so as to access purchasing power ( although this process destroys this same purchasing Power)

If we look at the Irish jurisdiction which is the current model pupil of current capitalism this is happening right now.

However Greece is perhaps not “dynamic ” enough yet I.E. It holds on to elements of traditionalism which prevents it accessing purchasing power using whatever absurd rules capitalism cooks up.

Greece is very much preforming as a sort of theatre of the most absurd.

A Peter Breughel painting but now on a much larger canvass. ( the now defunct nation state rather then the destruction of the village and its commons of yesteryear.)

Greeks perhaps continue to shit on a world turned upside down( yet again) for no apparent reason.

The crisis is really a inability of the people to conform to the new capitalistic doctrine.

The source of the problem is therefore the concentrated nature of the money power

We can logically infer that the Greeks are a more adjusted people then the rest of the zoo animals in the European wildlife park.

Capitalism endeavours to make people even more abenormal then they have become since the rise of Dutch like capitalism in northern Europe all those centuries ago.

The problem with the Argentina example is that they have now thrown it away by failing to take on the embedded agricultural oligopolies in the country.

So the usual neo-liberal retort is to link Jefes to the current Argentina problems and say that’s what giving people work causes.

You can never win because it isn’t a scientific argument. It’s entirely political, backed up by a load of impressive sounding mumbo-jumbo with lots of arcane equations to fool the gullible.

Less like science, more like skin cream.

Bills mistake is to think of home help as a job.

No sometimes its a duty. ( only made possible with a closed loop purchasing power system and or legal protection)

We can see the true objective of the liberals in Ireland ( gay marriage law etc)

Marriage at least from medieval times protected people from the worst ravages of the exterior monetary world by creating a internal monetized contract for real family units.

Wage slavery wiki.

“Fascist economic policies were widely accepted in the 1920s and 1930s and foreign (especially US) corporate investment in Italy and Germany increased after the fascist take over.[61][62]

Fascism has been perceived by some notable critics, like Buenaventura Durruti, to be a last resort weapon of the privileged to ensure the maintenance of wage slavery:

No government fights fascism to destroy it. When the bourgeoisie sees that power is slipping out of its hands, it brings up fascism to hold onto their privileges.[63]”

What people did not get about the recent referendum in Ireland.

Its objective was to split up the traditional family unit and monetize it.

I.e. it is a classic fascistic policy.

Indeed it was fully endorsed by the American corporate sector …….funny that.

It is hard to continually ignore evidence.The epiphanies of mainstream economists

will count for little thou.Their own sums do not add up ,cutting taxes ,cutting deficits

and maintaining current public services let alone any targeted state spending on

any kind of job creation.The political right are already abandoning previously treasured policy

commitments to the police and defence.

I suppose one paradoxical policy agreement which could gain traction accross many

flavours of OECD government could be rises in the minimum wage but that seems

to conflict with the international competitiveness narrative.

Follies unleashed are hard to reign in especially as they have further concentrated

wealth and power.Dark times indeed.

Does not the rise of non-standard work alongside mass unemployment constitute

a real pragmatic logistical difficulty to implementing a universal job guarantee?

Closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.Three decades at least of political economic policy

has changed the OECD labour market out of recognition from the era of the post war settlement.

(the hard working ,badly treated working poor were still abundant then although the direction of travel

was very different)

This site was responsible for a personal’ Chartalist conversion’.I would love to embrace your confidence

in a simple proscription and yes I do realise you do not offer a job guarantee as some kind of economic

let alone social panacea.But I remain utterly unconvinced in the ability of employers to compete with

the state in providing a living wage with dignity to enough workers particularly after a decades long race

to the bottom.

I know we don’t want employers who can’t provide a decent job.I have nothing against the

state offering work which would be in effect be at lower wages than the private sector can

offer in a downturn.

What goods and services would job guarentee workers provide for purchase for those

workers themselves when they collect their wages?

I also doubt the vote winning capabilities of aiming proscriptions at the the unemployed section

of society.

KH,

Job guarantee is open to everyone not just unemployed. It eliminates bad jobs.

Tight labor markets create dynamic efficiency to the benefit of the economy. That is so true on so many levels! I have to etch that into memory. Efforts to increase productivity are incentivised as are jobs that fit the existing education, experience and aspirations of the workforce ie the public. Brilliant!

Most businesses are focused on how they can more efficiently gain profits to the shareholders and never consider their own ongoing prosperity depends on workers being employed and able to consume what they produce.

The poor spend all their money.

Only the rich can hoard money.

Capitalism is buy and sell movement of money amongst people.

Is that a fair summary of your entire long winded, with lots of big words, piece?

The other is Gandhi’s observation, People’s Politics Are Their Daily Bread.

At no time in history has leaving the poorest in starvation ever been a good idea.

England could blow.

We have all forgotten the English mobs of old.

Not a happy thought.

Bob,that is exactly my point!

The job guarantee eliminates bad jobs!

It is not just for the millions who are unemployed or people who are in the new

growth area of the employment market the non- standard jobs described in this blog

but also for all those in onerous minimum and low wage jobs .

There are not enough good jobs out there.

This is the huge problem not only have the neoliberals taken over our democracy they have taken over the politcal levers as well. They control everything.

In my view economic policy will have to change in the UK regardless of this control. The sectoral balances of the UK show it must.

The only reason Osbourne managed to do what he did the last time ( make so many low paid jobs during austerity) was because when he took over the non governmental sector was at a surplus of +9%.

In 2010 the UK sectoral balance looked like this..

Non governmental sector +9%

Trade surplus +2%

Government sector -11%

Now it looks like this

Non governmental sector -1%

Trade surplus +6%

Government sector -5%

This shows clearly the effects of austerity on the UK private sector.

Osbourne is never going to be able to carry out the cuts he wants to the defict from a starting point of -1% in the non governmental sector. If he does then the real effects we all expected the last time will happen. This time there will be very real reductions in GDP growth and majot job losses moving into a recession.

When I look at the UK sectoral balance graph for the UK one period jumps out at me and that is Q1 in 2010. I think 2020 will look roughly the same.

It looked like this…..

Non governmental sector was running an incredible -9% defict ( how can that be ? without causing serious problems ?

Government sector was in a 6% surplus !!!

Trade surplus was 3%

Then it all becomes clear during that time real GDP quarter by quarter growth dropped from a high of 8% to 2%

If Osbourne and the EU continue on this path of madness we are all going to be in big trouble. He won’t have a non governmental sector surplus of +9% to save him this time.

Kevin

I’m not sure but I think you’ve missed the point of a job guarentee.

You say

” But I remain utterly unconvinced in the ability of employers to compete with

the state in providing a living wage with dignity to enough workers particularly after a decades long race

to the bottom ”

and

” What goods and services would job guarentee workers provide for purchase for those

workers themselves when they collect their wages?

I also doubt the vote winning capabilities of aiming proscriptions at the the unemployed section

of society.”

Surely the point is the goods and services the job guarentee workers provide are going to benefit everybody as a whole and in the long term including the private sector. Which would advance human well-being, protect the environment and allow workers with lower levels of education to fully participate in meaningful work.

It would also create a pool of workers that the private sector can hire in the future at less cost because traning costs would be lower than taking someone from welfare who have never worked for years.

Also, when they get their wages. The goods and services they buy are also going to help the private sector enormously. The private sector will be able to invest and grow as they supply these workers with what they want. This will also help employers in the long run to compete with the state when they provide a living wage under the job guarentee. Those that don’t die and that’s the way it should work.

It is a win – win circle that feeds itself.

This would not be done to win votes it would be done to

a) Help society as a whole

b) Help those that can’t get work

c) Help the private sector as living standards are raised from £72 a week.

I’m also sure the 40% of people who don’t currently vote and who benefit from this just might vote for whoever puts it in place. Will that have an impact on those parties who win elections with less than 35% of the vote? Damn right it will.

Sorry in my orginal post I Said

“When I look at the UK sectoral balance graph for the UK one period jumps out at me and that is Q1 in 2010”

It should have said Q1 in 2000

Neil Wilson: If you have the time (and inclination), could you expand a little more on the Argentina case? I have yet to see your argument, the general MMT argument regarding Argentina, clearly spelled out. Here or on 3Spoken would be very useful. Bill has talked usefully of the Jeffes program and Randy Wray wrote, a couple of years ago, on the Argentinian case, but for some of my skeptical latino friends, a more complete argument — I mean one identifying actors more precisely and the cause and effect on inflation etc. — would be most helpful. Thanks for the info above.

Anyone who has followed this debate carefully over the last two decades (MMT or even Keynesianism versus monetarism and neoliberalism) will know that heterodox economists like Bill Mitchell have been proved right very often in their predictions. On the other hand, neoliberals and “austeritarians” (like the Troika) have been proved wrong very often. It’s a sign that theory is basically correct when it makes consistently correct predictions and that theory is incorrect when it makes consistently incorrect predictions.

The interesting thing in all this is neoliberalism’s cavalier disregard for both empirical facts and for humane policy toward poor people. Te elites are not interested in truth or humanity. And they don’t play fair or nice. One wonders what will be necessary to change things. My own thinking is that matters will have to come to a crisis point before any real change occurs. The twin crises looming are basically the internal and external contradictions of capitalism. The internal contradiction between labour and capital has been modified by advanced automated machine production. It now becomes the conflict between the masses of people (who may or may not have any work) and the tiny rich elites plus their managerial and security apparatus. The external contradiction is between the capitalist economy and nature (the physical and ecological systems of the biosphere).

Derek I have read all off bills blogs on the job guarantee and am still unconvinced.

Which is strange because I find him very convincing otherwise.It is not that

I have any principled objection too a JG and do not see the advantages of a tight labour market.

It is a pragmatic logistical concern .As bill points out in this specific blog and many others in the

last 35 years under a Neo liberal onslaught labour markets across the OECD have deteriorated

structurally as well as cyclically.

Introduction of a job guarantee in this labour market would prove very popular in the sense

that a lot of people would make themselves available for it.This would provide a challenge

to the state in logistics and resources.It would provide a challenge to the private sector

to raise pay and improve conditions to compete.Currently despite low pay and insecure

conditions the private sector can not provide enough hours of work to those who want them.

It would seem reasonable to suggest that competition from the state in the form of a JG under

these conditions would mean rising prices as firms try to protect their profits and bankruptcies

when they fail.

Moving people from unemployment ,part time work and current onerous low paid employment

onto minimum wage JG jobs would provide some fiscal stimulus but remember those people

already receive benefits and now would produce less goods and services for sale.I think there

are better more effective forms of fiscal stimulus to raise aggregate demand to achieve full

employment and support the low paid eg targeted skilled government jobs in Health ,education,

mass transportation,nonCo2 producing energy ,housing and universal citizens wages.

BY the way I think you are absolutely right on the fantasy land of the Tory economic ‘plans’

just as in the USA with private sector surpluses moving downwards and negative sustainable

growth will be impossible

Inequality – Bill bowls full length balls but the batsmen refuse to play it

Bill’s missive on widening income disparities combines facts, insight and erudition borne of compelling belief.

The closing lines reiterate a persuasive belief in the role of JG; combined with an inference that government could set the pay rate and conditions at a level that would narrow the inequality gap and create an obligatory benchmark .

This proposal is a provocative stance compared with the austere remedies associated with the IMF; who nevertheless apparently acknowledge the MMT standpoint on the harmful effects of inequality. It is surprising therefore (at this time of writing) that a lively intellectual discussion has not erupted.

It is not as though alternative viewpoints don’t exist. There have been many disagreements over the importance of JG. Where are all those voices now; whose foresight presumably visualised the practical outcome of these alternative economic policies (ideologies).

In essence, JG provides a resoundingly beneficial outcome for its implementation. However, there will be practical shortcomings; remember the government is major player in this endeavour – a capricious entity if ever there was one. It will come under opposing influences, not necessarily confined to Capital v Labour, as it is possible to envisage policy repercussions advancing some groups of workers at the expense of others.

Dissenting voices that can identify practical obstacles to overcome need to highlight these outcomes. The alternative is that JG is introduced on an emotional wing and a prayer.

“Moving people from unemployment ,part time work and current onerous low paid employment

onto minimum wage JG jobs would provide some fiscal stimulus but remember those people

already receive benefits and now would produce less goods and services for sale.”

Why the assumption that the JG will produce less goods and services for sale?

Each and every unemployed who choose a JG will produce more than they do as unemployed and for that they’ll get paid more than if they’re on unemployment benefits.

What is it in the JG that will make those now in part time work and current onerous low paid employment less productive if they choose a JG instead of their part time work and current onerous low paid employment?

“It would seem reasonable to suggest that competition from the state in the form of a JG under

these conditions would mean rising prices as firms try to protect their profits and bankruptcies

when they fail”

That is fixed output thinking and is incorrect.

Consider this. If a hairdresser gets a queue, do they

a) work harder and longer to get the queue through the door and bank the extra profit.

b) close the shop and put up their prices until the queue goes down.

What happens of course is a). And if anybody tries to do b) then they get outcompeted by those doing a).

So if you have a market that makes b) stick then you should bring in the competition authorities to investigate the inevitable oligopoly and start breaking it up to increase competition.

So not only does the Job Guarantee increase demand and increase output, it also relieves the state of any consideration of whether a particular business should exist. And that means the state can return to its proper role – ensuring that markets deliver maximum output at best cost for consumers by holding the feet of business to the fire of competition.

@Derek Henry

How Osborne got away with his austerity program was to effectively abandon it for brief periods in order to raise GDP numbers, and them reintroduce it again sub rosa. You can find a good discussion of this deception in William Keegan’s The Economic Experiment of Mr Osborne. Then you have to ask yourself who exactly is benefiting from this rise in GDP. It generally isn’t the 90, or 99, %. To say, as Osborne does, that GDP is up is to say almost nothing.

Neil no I am hoping for growth .I just think there are better and more efficient ways of increasing

demand and output than the JG.I also think in the current labour market battered by 35 years

of neo liberalsm it is not just the unemployed but as this post suggests non standard workers

and low paid full time workers in onerous work which will want a JG position.Its implementation

would be logistically impaired.

I am not against JG in principle and am certainly in favour of the state offering work to those

who the private sector have left behind but as the central proscription of much needed stimulus

measures I find it unconvincing and potentially chaotically wasteful.

“.I just think there are better and more efficient ways of increasing demand and output than the JG”

There isn’t – it’s the anchor that holds the whole things down.

The private system is systemically incapable of providing everybody with a job. It is simply irrational for it to do so in any productive economy based upon mechanisation. In fact we have pushed it so far it is creating pointless jobs of its own – most of the finance sector for example – that is tying up high level human resources that would be better deployed in the University sector inventing freely accessible new stuff that business could then leverage to improve real conditions.

You set the Job Guarantee at the living wage and let the cards fall where they will. The extra demand from that stabilisation process is what drives the rest of the system upwards. You then adjust the other fiscal settings so that the private sector bids away people from the Job Guarantee as much as it is able *without* creating bullshit jobs.

And of course the idea that people on the Job Guarantee are ‘wasted’ is to fall into the fallacy that public provided jobs are somehow inferior to private provided jobs. They are not. They are the same quality.

Neil I am afraid wishing for something does not make it so.

I do agree if we are to have a buffer stock ( at that is not the ideal) to employment

it would be much better for the individuals concerned and society as a whole

for that to be a buffer of JG jobs than unemployment.I do not think it is

a realistic assessment of the economy to think such a transition would be smooth.

Even when there was no buffer stocks when many OECD nations had only

frictional unemployment back in the post war settlement day the working poor were

still with us today as this blog details the working poor are on the rise.

To be a buffer stock to employment the buffer has to be less desirable than what

it is buffering.Set the Job Guarentee at the living wage and the cards will fall with

the state needed to organise work for an incredibly large amount of the population.

As you say such employment will not be wasted but it will not provide the things which

people now consider required for a decent living.As much of the working poor currently

recieve government benefits to be able to live it will not provide that much extra demand

either.

I absolutely share your disbelief in a free market mechanism to deliver a decent living for

most people.We need the power of the state to spend tax and regulate to side with the

majority against the wealthy and powerful . The problem is how we move from where we

are to where we want to be without chaos and shortages .

“In fact we have pushed it so far it is creating pointless jobs of its own – most of the finance sector for example – that is tying up high level human resources that would be better deployed in the University sector inventing freely accessible new stuff that business could then leverage to improve real conditions.”

Employer of last resort policies don’t crowd out the private sector, by design. The public sector should deliberately crowd the private sector out of low wage activity and into high skilled activity. The reason that public sector research achieves measurably better results is because public sector research does not make decisions based primarily on the profit motive.