Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Casual work traps workers into low-pay and precarious jobs

I am giving a presentation tomorrow in Melbourne at a conference on Annual Skilling Australia and Workforce Participation Summit. My topic is Making Australia a “full employment economy” and that topic stands out from the others which are all about the mainstream pre-occupations of participation and training. My view is simple – if you offer someone a job and a training slot you solve the participation problem and provide them with a paid-work environment to develop their skills. The most effective skill acquisition comes from training within a paid-work context. I am also talking about how workers get trapped in a low-skill, low-pay circle of disadvantage and the increasingly casualised Australian labour market is reinforcing that pathology. This proposition, of-course, runs counter to the mainstream view that has justified the growing precariousness of work in Australia (and elsewhere) as being a market response to the desire by workers for more flexibility. They also argue that casual work is a “stepping stone” into better jobs and provides unskilled workers with a transition from low pay to high pay. The evidence does not support the mainstream view – why would we be surprised about that. The evidence is categorical – casual work traps workers into low-pay and precarious jobs.

The Sydney Morning Herald had a story last week (June 24, 2011) – Casual work: a blessing or a curse? – which touches on one of the big debates in labour economics which the mainstream economists have tried to suppress.

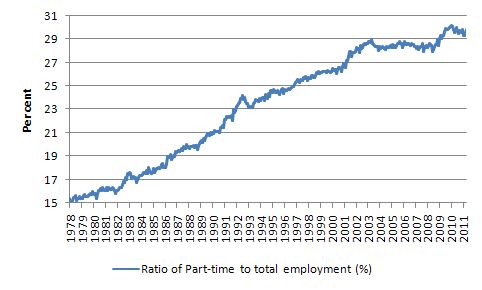

The following graph shows the ratio of part-time employment to total employment for Australia from 1978 to May 2011. While the trend has clearly been upwards there is also clear indication that the recessions (1982, 1991, 2000, 2008) pushed the trend growth upwards. The ratio has doubled over the sample period.

ABS data shows that around 50 per cent of Australia’s part-time workforce are engaged for less than 20 hours per week.

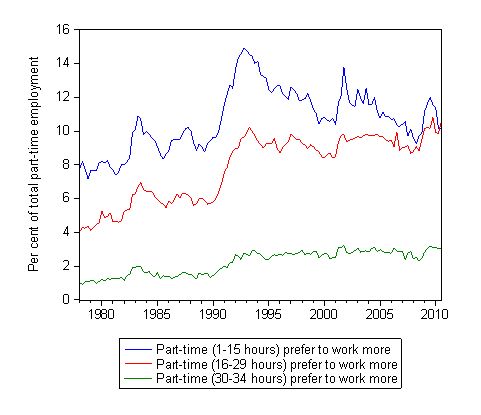

The following graph shows the number part-time workers who preferred more hours of work per week as a percentage of total part-time workers by three hours bands: 1-15, 16-29 and 30-34 (as at end of 2010). It is clear the that the problem of underemployment is usually dominated by the workers who are in the 1-15 hours per week band, although workers in the 16-29 hours per week band are now approaching the level of the 1-15 hours per week group.

We cannot tell if these were new jobs created as full-time work collapsed or further hours rations on existing part-time jobs. The cyclical nature of these series is very striking.

As growth collapsed in early 1991, underemployment rose sharply and this was spread over all the hour-bands shown but concentrated at the lower end (1-15 hours). Once growth resumed the proportion of part-time workers in the higher hour bands (16-29 and 30-34) barely altered but underemployed in the 1-15 fell.

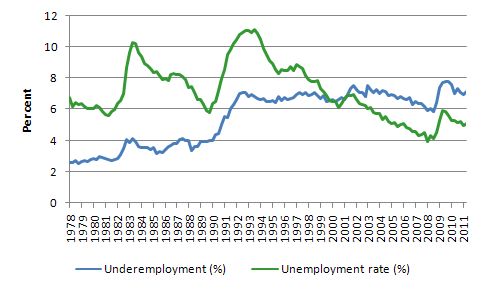

The next graph shows the evolution of unemployment and underemployment in Australia from 1978. The impact of the three major downturns in that sample period (1982, 1991, and 2009) is clearly evident.

The Australian labour market thus increasingly fails to provide enough hours of work to satisfy the preferences of the labour force. While underemployment rose in the 1982 recession, it was the 1991 recession that led to a sharp increase and a new attractor level. The growth period after the 1991 recession led to reductions in the unemployment rate but only very modest reductions in the rate of underemployment. In the current economic downturn, the rise in both measures of labour underutilisation was sharp but smaller than the 1991 recession.

As a result it is now unlikely that a persistent new level will be established in these series. But the striking trend since the 1991 recession has been that underemployment is now a significant issue and that as jobs have been created and absorbing the unemployed, a strong percentage of those jobs have not been providing enough working hours to satisfy the preferences of the labour force.

The rising part-time to total employment ratio and the increased incidence of underemployment has also been accompanied by a rise in the importance of casual employment.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) define casual employment as all employees that do not enjoy access to paid holiday and sick leave. Casual workers tend to be part-time and dominated by female workers in retail trade and in accommodation, cafes and restaurants. The jobs tend to be low-skilled and low-paid.

The rate of casual employment has risen significantly over the last decade. Australia ranks second across the OECD in terms of the proportion of part-time workers in total employment (around 30 per cent in September 2010). The Netherlands has the highest incidence of part-time work (48 per cent). The OECD average in 2006 was just over 20 per cent. In 1982, the proportion of workers who were considered to be casual in 1982 was 13.3 percent and by 2003 this proportion had risen to 28 per cent.

The SMH article (noted above) says that the rate of casual employment in Australia is “among the highest in the OECD and trade unions aren’t happy about it”.

It is clear that the unions have good reason to be concerned – and – it is far past the time that they should now be doing something about it.

Not only do casual workers miss access to paid leave and sick leave they are also excluded from some of the other legislative protections (including unfair dismissal).

A large proportion of casual jobs were precarious with respect to the predictability of earnings, the hours offered, the opportunities for skill development, low union representation, and an increased vulnerability to occupational health and safety hazards.

The ACTU spokesperson noted that:

Casual pay also has many other hazards … such as variances in pay that change week by week. Periods of work can be accompanied by long gaps or really short call-in times, and many casual workers “find it hard to predict their income, to pay the bills and make ends meet, let alone plan for the future or save to buy a house”.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) is currently running a – Working Australia Census – which aims to document:

… the challenges … in today’s workplace … about job security, balancing work and family, cost of living pressures and fairness …

The SMH reports that the preliminary findings suggest that “Twenty-four per cent of employees go to work when they’re sick because they don’t want to miss out on pay, and many find it difficult to object when they’re asked to do unpaid work from home”.

It is also known that casual workers face a higher likelihood of forced dismissal; female casual workers are “less likely to take maternity leave” and job satisfaction is lower than for non-casual workers.

So it seems obvious that casual workers receive reduced entitlements, inferior training opportunities, poor working conditions (diminished quality of occupational health and safety) and become trapped. The idea that poor work conditions are compensated for by higher pay does not accord with the reality of the labour market.

The SMH article also reported the views of a researcher at the conservative (free-market inclined) Melbourne Institute (at the University of Melbourne). They choose to run the line that casualisation is a good trend.

The mainstream argument is that casual work is more flexible – and suits students. They also continually argue that the loss of entitlements is made up by the pay loadings, a point that is categorically rejected by industrial court evidence. While casual rates per hour are higher they go nowhere near making up for the lost holiday pay, sick pay and other entitlements.

The mainstream also argue that casual work provides a stepping stone for unskilled workers to enter the labour market and gain experience which then allows them to progress into more secure, full-time work.

The SMH article quotes the Melbourne Institute researcher as saying:

Employers who hire casuals are overwhelmingly small businesses … The reason employers are reticent to hire people is that they don’t want to face the dismissal costs, so casual workers make it easier to hire.

That is a standard neo-liberal argument that my profession makes every time the topic of casual work comes up. They assume that job- and employer-related characteristics are irrelevant to the determination of the transition rates from casual to non-casual employment.

The mainstream argument posits that:

1. Casual employment provides work experience which enhances human capital formation while unemployment leads to skill atrophy.

2. Casually employed workers signal their ability and willingness to accept work by accepting casual employment.

3. (Casual) employment enlarges the social network of job seekers, which in turn, provides valuable linkages to a wider knowledge of job vacancies.

These so-called advantages are then used to justify the claim that job seekers have a higher probability of gaining a non-casual job if they are first in casual employment rather than from a state of unemployment.

I have done quite a bit of research on this topic with a colleague from James Cook University (Dr Riccardo Welters). Some of this text today is taken from joint work that Riccardo and I have done. We have sought to investigate the proposition that casual work acts as a stepping stone to more secure work.

Some of the mainstream research used to substantiate the stepping stone argument does not exclude students who combine school/study and casual work. This biases the results in favour of the stepping stone argument. Why? Because students who engage in casual work to support them while studying and then upon graduation enter a professional occupation are not representative examples.

The sucessful transition from casual work to full-time work has nothing to do with the casual work experience. The casual work has nothing much to do with the skills they subsequently garner in their professional capacity which requires only a university qualification for entry. Further, the casual employment undertaken typically bears no relationship to the industry or occupation that they enter after finishing their studies.

So in research studies, one must always exclude this cohort.

Some conclusions we have reached:

First, we consider the predictions from Dual Labour Market theory – or Segmented Labour Market theory to be a reasonable description of the structure of labour markets in most countries.

SLM theory argues that the labour market is segmented into two separate labour markets each with different processes for allocation and reward. These segments resist transitions from each other.

The most basic demarcation is between the Primary Labour Market (PLM) and the Secondary Labour Market (SLM). PLM workers are typically employed in a tight internal labour market structure which provides for career advancement and tend to search for jobs within the firm while already employed. The jobs are secure and relatively well-paid.

The SLM is characterised by low-paid, insecure “dead-end” jobs which have high turnover rates. The jobs do not have well-defined career ladders and offer very little training for higher productivity.

While the PLM worker searches for new ways in which to climb the career ladder, the SLM worker usually searches to avoid being sacked.

Given the lack of mobility between the “segments”, a SLM worker will typically not make the transition into the PLM. Workers thus become “trapped” in poor jobs with spells of unemployment intervening periods of low paid work.

Our research shows that casually employed workers find it harder to transit to non-casual employment in Australia if they start their working life in the secondary labour market – that is, if they are working in low skill occupations.

Second, we have found that casually employed workers find it easier to move into non-casual employment if they are employed in large firms rather than small firms. The reason is that the large firms provide exposure to a broader and deeper social network.

Third, the longer a person is in casual employment the harder it gets to exit that state. This is called “duration dependence” in the literature. The evidence suggests that any period beyond three years triggers this constraint and traps the worker into a circle of precarious casual work with intervening periods of joblessness.

An important part of this research is that the transition probabilities are not exclusively defined by the individual characteristics of the worker, which is usually assumed by the mainstream paradigm.

That is, they consider individuals make choices to invest in skills and then their destiny is in their own hands. The evidence clearly rejects that idea and indicates that “environmental” factors – which are beyond a worker’s control are important.

Conclusion

The increasing casualisation of the labour markets around the world, with Australia leading the race with a few other nations, is another defining characteristic of the neo-liberal era. It is another manifestation of how governments have relaxed regulations and actively targetted worker protection by introducing anti-union legislation to favour capital.

Clearly, some casual work is beneficial to those who seek flexibility and have what is called an “instrumental” attachment to the labour market. For example, a student is instrumentally attached to the labour market by using casual work to fund their studies.

But the evidence is indicating that a growing cohort of workers are locked into a circle of disadvantage where low-paid casual work is interspersed with spells of unemployment. The mainstream idea that casual work is a “stepping stone” into better jobs and provides unskilled workers with a transition from low pay to high pay is not supported by well-designed research. The evidence is categorical – casual work traps workers into low-pay and precarious jobs.

Rushing to catch a plane so …

That is enough for today!

Yeah – I checked the agenda: must be like lecturing little owls on sunlight!!

Minor point Bill but, since the new look site, when I print out the blog, I’m not getting all the charts.

In this blog, the middle one doesn’t print.

I’m not sure if the problem is your end or mine but I thought I’d mention it.

Hope you convince Melbourne University of the immorality and evils of exploiting workers through casualised work.

Increasingly casual workers are experienced, skilled and highly educated and they are expected to act professionally when there is no certainty about where their next shift will come from. You read about my experience on The Age / SMH article.

I can remember when frail, elderly mum was hospitalised at the Epworth the only time she perked up, in indignation, was when the nurse, originally from Chile, but educated and trained in Adelaide, explained that he was a casual who could survive in Melbourne because he lived with his brother, who was understanding about intermittent rent payments. He was only hired 30 minutes before he was needed on the ward. From a patients prespective it wasn’t good because he didn’t know the ward procedure or hospital protocols. At that time the Epworth hired a charge nurse to run each ward and hired casuals at the start of each shift as required.

At the RIO AGM in Melbourne in 2010 miners from Mt Thorley Coal Mine in the Hunter Valley asked management a number of questions including, and I paraphrase here

“Why is the company bringing in migrant workers under the 457 skilled migration visas to work in the mine when there are local men working casually who would dearly like a permanent position”

I assume miners, like nurses and teachers are not allowed in the work place unless they have the appropriate tickets, training and clearances as mandated by government fiat.

Sorry I am on a roll, not sure anecdotes help your cause.

I have worked as a casual teacher, and on any given day 10% of the teachers in Victorian classrooms are casuals. These workers have university degrees, teaching qualifications, teacher registration, police working with children clearances. They should earn $265 per day, but agency fees to the teacher are $40, agency fees to the employing school are $40 and these fees come out of the $265. The agency rings the worker up at the start of the shift offering work.

Its as degrading and disgraceful as the bull ring that used to operate to hire casual waterside workers and labourers from the 1920s to 1970s although it’s hidden today behind mobile phone calls

Camp Australia was established by 2 primary teachers to provide outside hours school care. They hire the staff and centrally buy the snacks kids eat – no sugar, no peanut products etc. Each school has a part time supervisor then casual carers are employed so there is always 1 staff member per 10 kids. As kids go home, staff finish their shift. Trainee sports teachers were engaged to supervise the run around games on the oval from 4 to 5. The kids parents paid per session, not per hour. So what! The firms founders live in mansions in Brighton’s Golden mile. The workers all have current working with children checks. Less than 20% of workers are trainee teachers.

I think the lasting Kennett leagacy is that working conditions for casuals in Victoria are harsher than conditions in NSW.

Universities and TAFEs are amongst the largest employers aof casual labour. Universities might be able to get away with hiring casual tutors who are grateful for the status and part time work while they attain higher degrees, it’s not always good for theur students.

TAFEs struggle to find and keep teachers which 2 years industry experience when they offer an hour of paid work on Monday, an hour on Tuesday and 2 hours of Thursday, all for $58 per hour class contact time. How many employees can leave their major employer to slip out to teach at TAFE? These employment practices are having a deleterious effect on the nation’s ability to deliver technical training to our young people. To the extent that I would recommend that kids who want to do apprenticeships should consider joining the army.

About the only good thing I can say about the first graph showing the rise of casualisation, is it looks like it may have peaked at that ~30% level.

Billie, I work for tafe in nsw (admin) and can confirm the vast majority of teachers are employed as casuals, with a slowly shrinking core of greying permanent teaching staff. There is even quite a lot of casualisation amongst the admin staff. At the college where I work I would estimate a good 20% are employed through temp agencies, many for years at a time on decidedly inferior pay and conditions to the permanent staff, with the agencies creaming of a handy profit on each of these staff members.

Those of us in full time jobs that are working poor are fooked as well. After paying rent, groceries and utilities and putting moola aside for running my ailing car there is scant left for self-improvement. Earn to much for rent assistance. No chance of community housing. Hell, I walked almost 4 hours a day to work for 7 weeks whilst saving up to repair my car just after Christmas.

I’m a hard worker. Don’t take sick days. Ensure that I’m the “go to” guy when the boss wants to ensure that a task is done correctly and quickly. Yet I honestly feel like I am a slave. Free range slave but a slave all the same. Can’t quit because then I’d be on the street. Can’t find anything that pays better because employers KNOW that they have you over a barrel.

“I’m a hard worker. Don’t take sick days. Ensure that I’m the “go to” guy when the boss wants to ensure that a task is done correctly and quickly”

You are a slave. A wage slave is still a slave.

“Can’t quit because then I’d be on the street. Can’t find anything that pays better because employers KNOW that they have you over a barrel.”

And that’s the reason we need a Job Guarantee. To give an alternative to wage slavery. Once people have an alternative then the negotiations over what is given in return for payment can become more equal.

Remember that for a market to be ‘free’, walking away from a bad deal has to be an option. Any market that doesn’t offer that option isn’t free.