Regular readers will know that I hate the term NAIRU - or Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment - which…

A Greek exit would not cause havoc

I am in Seoul (South Korea) today and tomorrow working on a project I have with the Asian Development Bank. It is a mega city that is for sure – more than 10 million in the city itself and 25 million in the nearby areas linking Seoul to the airport. Quite a place where you see massive public sector involvement in planning and infrastructure developing aiding mega capitalist firms. But I will report on the work I am doing here in due course, once government clearances are available. Today, I am focusing on the Eurozone after I read a report sent to me that was written by a German consulting firm of some note predicting havoc if the Greeks exit the Eurozone. The European press gave the report oxygen that it does not deserve. It is another example of a highly selective and “fixed” study, which is influencing the debate because of its scare value. It substance is largely zero. The reality is that a Greek exit would not cause havoc and is to be recommended (about 3 years ago)!

There was an article in the EU Observer (October 18, 2012) – Study: Greek euro-exit could start €17tn ‘wildfire’ – which chose to publicise a “study” from a German “consultancy” that was predicting, should Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain leave the Eurozone:

… a lengthy worldwide recession … [stretching from the US to China and] … major strains on the social fabric and political stability …. [in the euro-departing countries] …

With riots in the street in Spain and Greece already becoming a regular phenomenon one wonders how bad the alternative will be.

And there is worse to come over the next decade. The costs of having 55 per cent of a nation’s 15-24 year olds unemployed will start to come hometo roost in the years ahead – a harvest of sorts for staying in the Eurozone.

The report mentioned by the EU Observer – Economic impact of Southern European member states exiting the eurozone is, in fact, a crafty piece of deception, hiding behind simulations produced but “macroeconomic world model”

In papers from the same organisation they keep quoting this VIEW model and by way of explanation write “see box” which on inspection says the following:

The VIEW model is a macroeconomic model that is used to make projections and simulate economic scenarios. The simulations in our study encompassed the world’s 42 states that account for more than 90 percent of the world economy and were based on the following parameters: supply and demand; labour markets; government finances; as well as exports, imports, currency rates and so on. Thus, the model also factors in the interrelationships between the various states as regards these parameters.

Which tells a person like myself, who is an expert (as far as they go) in macroeconomic models (stochastic or otherwise), about zip!

I have searched the organisation’s site for technical papers, which would describe the structure of the VIEW model, and nothing was revealed. I am always deeply suspicious of organisations that claim to use a large macroeconomic model to justify the statements they make about economic policy and such, but who refuse to make public the structure of the model for scrutiny.

I once was recruited by an organisation (but never started with them – a better alternative came up at the same time), which had long trumpeted its “model”. The impression one had of the “model” from public speeches given by senior officials in that organisation and the breadth of the forecasts they produced on a quarterly basis (derived from the “model”) was that this was a very significant structure.

At the interview, once it was obvious I was going to be offered the job, they asked me if I had any questions. I asked the “senior modeller” who was present if he could provide me with a paper outlining the equations and structures that made up the model and the estimation techniques used etc, so I could come up to speed very quickly if I was to start work with them.

There was a pause, some looks between the members of the selection panel, some sniggers and then he said – “well it is sort of like this – we have a Phillips curve … [Bill notes: that is, one simple estimated equation] … and then we get out the envelope and write down on the back of it whatever we think is going to happen over the next quarter” – at which point there was laughter all round.

I was young and felt a bit duped but soon learned about a lesson about duplicity. I have also learned along the way about model structures and how one can get results from specific structures. So when an organisation keeps producing very selective results claiming that their model simulations produced them I get a feel for the underlying structure that must be in place.

In that sense, I consider the VIEW model to be an inappropriate vehicle to rely on for helping us understand what would happen if Greece and/or other nations exited the Eurozone.

The EU Observer article uncritically parrots the conclusions of the Report – never once wondering what was driving the conclusions or whether they would stand up to scrutiny from an expert in the field.

The tenor is set from the start:

The nightmare scenario of Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain leaving the euro could cost the world economy €17 trillion …

That seems a very specific number – 17 trillion euros. But then you see that that amidst all the “Modelling Talk” in the Report, the authors are forced (on page 6) to admit:

While Greece defaulting on its sovereign debt and leaving the European Monetary Union would in and of itself have a relatively minor effect on the world economy, the consequences of this event are to all intents and purpose shrouded in mystery.

A mystery means that they haven’t a clue.

But that doesn’t stop them producing horror-story numbers of currency collapses, real GDP growth reductions of massive proportions sening “ripples around the world economy”, which would cause the US to fall by “€365 billion and the Chinese economy would lose €275 billion.”

The Report claimed that a “wildfire” would result from the exit of Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. Poor Ireland doesn’t get a gig in the Report but presumably its exit would add to the “inferno”.

Apparently, Greece’s real GDP will experience a cumulative decline of the order of 94 per cent in 2013 should it exit. That is, Greece’s economy would largely disappear next year if they chose to abandon the Euro.

None of which is remotely true.

If you read the Report (and I wouldn’t waste my time if you trust my judgement) you will come across statements like this:

They only assume a 60 per cent default by Greece if it reintroduced its own currency. They claim the “remaining 40 percent of Greece’s debt would continue to be denominated in euros”. Why would they assume that? I would advise the Greek government to follow the lead of the Argentinean government and default on all euro-denominated debt and offer a drachma-conversion rate.

They also assume that the credit defaults would force other Euro-member states to absorb the losses within their own budgets and this:

would force the governments affected to consolidate elsewhere by either cutting their expenditures or raising taxes. Such measures reduce demand for goods and services, which in turn reduces economic output and increases unemployment.

Of-course, the ECB could just internalise all defaulted debts – that is, write them off. But this also brings into relief the absurdity of the fiscal consolidation process in the Eurozone, where governments are forced by rules, that were made up off the top of their heads (the 3 per cent rule) without any reference to economic realities or contingencies, to pursue pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

At the heart of the problem is the structure of the Eurozone – its lack of fiscal capacity at the member state level; the reluctance of the ECB, as the only real fiscal unit to act as such; and the rules that restrict what fiscal capacity the member states actually have.

The ECB has recently shown – with its long-term loans and Securities Markets programs – that is can provide funds to both governments and private banks at whatever level is required to keep the system functioning. Thus, any debt write-offs from the GPSI’s should have a very small impact on government net spending elsewhere in Europe.

The Report claims that “Greece’s public and private sector debtors would also need to write off 60 percent of their outstanding loans”. which:

According to our calculations, these losses would presumably have a direct negative wealth effect on household income for the relevant year; and this in turn would reduce housing start-ups and consumer spending

While the Greek creditors lose, the debtors gain. Further, this assumes that the Greek government does nothing with its newly found fiscal capacity.

They then make the following statements about the budget in Greece after predicting a 50 per cent nominal depreciation of the drachma:

This devaluation would drive up the government-debt ratio as expressed in the new Greek currency, because this debt would have previously been denominated in euros. Hence introduction of a national currency would reduce Greece’s government debt ratio by a mere 20 percent; and what’s worse, capital-market confidence in Greece’s credit-worthiness would evaporate. Hence the Greek government’s sole source of revenue would be tax revenue, which in turn means that the Greek budget balance would be virtually zero in the lead-up to 2020.

Which really tells you a lot about the structure of their VIEW model.

Capital market confidence in Greece is already zero. Hence the bailouts in the first place. So Greece’s credit-worthiness is irrelevant and should not be included in any assessment.

What Greece would get back would be its own central bank and its currency issuing capacity. It would then move from using a foreign currency and having to fund all its public spending via taxes and then borrowings (now bailouts) to a situation where it issued its own currency and became free of any financial constraints.

Its Euro-denominated debt would fall to zero.

Its capacity to spend would not be constrained by tax revenue and it would be in a position to pursue whatever growth strategies it thought suitable for its citizens and industry structure.

The Report seems to misunderstand that being in the Euro imposes constraints that would not persist if Greece was out of the Eurozone. That is the whole point of exiting – to restore currency sovereignty and create possibilities that are non-existent within the Euro.

I will come back to the devaluation argument later.

The Report also claims that:

Greece switching to a new currency would also put a major dent in consumer and investor confidence … the aforementioned declines in demand for goods and services would not be limited to the state affected. In a world where individual state economies maintain highly symbiotic relationships with each other through foreign trade, falls in consumer demand in one state would soon spread to its trading partners. The result would be a worldwide decline in economic activity.

First, reflect on their earlier conclusion that “Greece defaulting on its sovereign debt and leaving the European Monetary Union would in and of itself have a relatively minor effect on the world economy.”

A few pages later they are predicting substantial inter-country spending multipliers. My prediction is that Greece’s default would have very little real economic impact elsewhere – perhaps a slight negative impact on German activity especially because it would reduce their capacity to export military equipment to Greece on its current terms and it would see its imports rising (as Germans rushed to bathe in the sunny Greek islands given how cheap Greek holidays will become for foreigners).

Second, consumer and investor confidence is tightly bound to the state of domestic demand and the labour market. An economy that is bleeding jobs and has 25 per cent of available workers without jobs and 55 per cent of its youth without work is hardly likely to invoke strong consumer and investor confidence.

But it is highly likely if the drachma depreciates and promotes growth in tourism and export sectors and the government ensures it promotes domestic demand by increasing its deficit and ensuring job creation is a priority – that consumer and investor confidence will rise rather quickly following a default.

I think the reality is more likely to be something like this.

It is clear that the Greek government would have to default on its Euro-denominated obligations which in the language being used in financial markets would prompt a “credit event”. There is a fear that there are very large CDS payouts linked to such an event but they would not be Greece’s problems and central banks in other nations including the ECB could deal with those. If they chose not to insulate the remaining economies from the consequences that would just tell you that they are incompetent.

It is often claimed that there would be drawn out contract litigation as a result of the default on euro-denominated contracts. But this ould be overcome by the Greek government passing “a currency law” which would define conversion rates between the Euro and the Drachma.

The Greek currency law would also specify that the new currency is legal tender for payment and settlement of debt in Greece, including all payments of public and private debt obligations.

That is what currency sovereignty means.

Short of a military takeover of the country, a sovereign Greek nation could defy all claims against it outside of the conditions that it sets in terms of its own currency.

The Greek government could defy the rest of the world completely (as in the early days of the Argentinean default) or offer re-denomination in terms of the new currency. Once re-domination was accepted then its so-called “sovereign debt” problem vanishes. It becomes a sovereign currency-issuing nation with debts only denominated in its own currency – which means it could always service those debts.

Should the bond markets decide that they do not want to invest in Greek currency financial assets then the Greek central bank – newly legislated to support the national interest could provide funding to the Greek treasury without any fundamental financial problems.

The German Report and their VIEW model completely disregards these obvious facts regarding the opportunities available to a sovereign nation with its own currency. The Greek government doesn’t have to lie down and die and pretend it is still bound to the SGP rules as if it was still in the Eurozone.

It would quickly learn it had new options and capacities and under political pressure from its people it would start using them.

Its new currency would depreciate – by how much is anyone’s guess. The likelihood is that the depreciation would be sharp and large. But its downward spiral would be finite and reversed as trade flows turned in favour of exports and the real cost of imports rose.

The German Report cites Argentina as an example of what would happen should Greece exit. So lets think about what happened in Argentina about a decade ago. Argentina, in part, provides a model for all nations that have surrendered their currency sovereignty courtesy – either via a peg of some sort of outright use of foreign currencies (as in the Euro case).

In April 1991, Argentina adopted a rigid peg of the peso to the dollar and guaranteed convertibility under this arrangement. That is, the central bank stood by to convert pesos into dollars at the hard peg.

The choice was nonsensical from the outset and totally unsuited to the nation’s trade and production structure. In the same way that most of the EMU countries do not share anything like the characteristics that would suggest an optimal currency area, Argentina never looked like a member of an optimal US-dollar area.

For a start the type of external shocks its economy faced were different to those that the US had to deal with. The US predominantly traded with countries whose own currencies fluctuated in line with the US dollar. Given its relative closedness and a large non-traded goods sector, the US economy could thus benefit from nominal exchange rate swings and use them to balance the relative price of tradables and non-tradables.

Argentina was a very open economy with a small non-tradables domestic sector. So it took the brunt of terms of trade swings that made domestic policy management very difficult.

Convertibility was also the idea of the major international organisations such as the IMF as a way of disciplining domestic policy. While Argentina had suffered from high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s, the correct solution was not to impose a currency board.

The currency board arrangement effectively hamstrung monetary and fiscal policy. The central bank could only issue pesos if they were backed by US dollars (with a tiny, meaningless tolerance range allowed). So dollars had to be earned through net exports which would then allow the domestic policy to expand.

After they introduced the currency board, the conservatives followed it up with wide scale privatisation, cuts to social security, and deregulation of the financial sector. All the usual suspects that accompany loss of currency sovereignty and handing over the riches of the nation to foreigners.

The Mexican (Tequila) crisis of 1995 first tested the veracity of the system. Bank deposits fell by 20 per cent in a matter of weeks and the government responded with even further financial market deregulation (sale of state banks etc).

These reforms loaded more foreign-currency denominated debt onto the Argentine economy and meant it had to keep expanding net exports to pay for it. However, things started to come unstuck in the late 1990s as export markets started to decline and the peso became seriously over-valued (as

the US dollar strengthened) with subsequent loss of competitiveness in the export markets.

Lumbered with so much foreign-currency sovereign debt the decline in the real exchange rate (competitiveness) was lethal.

The domestic economy by the late 1990s was mired in recession and high unemployment.

And then the “Greek scenario” unfolded. Yields on sovereign debt rose as bond markets started to panic – a vicious cycle quickly became embedded.

In 2000, under direct orders from the IMF (with the threat of refusal to maintain financial assistance – ring a bell?), the government tried to implement a fiscal austerity plan (tax increases) to appease the bond markets – imposing this on an already decimated domestic economy.

The government believed the rhetoric from the IMF and others that this would reinvigorate capital inflow and ease the external imbalance. But at the time it was obvious that it was only a matter of time before the convertibility system would collapse. They couldn’t hold back the flood waters.

Why would anyone want to invest in a place mired in recession and unlikely to be able to pay back loans in US dollars anyway?

In December 2000, an IMF bailout package was negotiated but further austerity was imposed. No capital inflow increase was observed. That was also an obvious prediction apparently not in the IMF forecasting model’s capacity to provide.

The government was also pushed into announcing that it would peg against both the US dollar and the Euro once the two achieved parity – that is, they would guarantee convertibility in both currencies. This was total madness.

Economic growth continued to decline and the foreign debts piled up. The government (April 2001) forced local banks to buy bonds (they changed prudential regulation rules to allow them to use the bonds to satisfy liquidity rules). This further exposed the local banks to the foreign-debt problem.

The bank run started in late 2001 – with the oil bank deposits being the first which led to the freeze on cash withdrawals in December 2001 and the collapse of the payments system.

The riots in December 2001 brought home to the Government the folly of their strategy. In early 2002, they defaulted on government debt and trashed the currency board. US dollar-denominated financial contracts were forceably converted in into peso-denominated contracts and terms renegotiated with respect to maturities etc.

This default has been largely successful. Initially, FDI dried up completely when the default was announced. However, the Argentine government could not service the debt as its foreign currency reserves were gone and realised, to their credit, that borrowing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would have required an austerity package that would have precipitated revolution. As it was riots broke out as citizens struggled to feed their children.

Despite stringent criticism from the World’s financial power brokers (including the International Monetary Fund), the Argentine government refused to back down and in 2005 completed a deal whereby around 75 per cent of the defaulted bonds were swapped for others of much lower value with longer maturities.

The crisis was engendered by faulty (neo-liberal policy) in the 1990s – the currency board and convertibility. This faulty policy decision ultimately led to a social and economic crisis that could not be resolved while it maintained the currency board.

However, as soon as Argentina abandoned the currency board, it met the first conditions for gaining policy independence: its exchange rate was no longer tied to the dollar’s performance; its fiscal policy was no longer held hostage to the quantity of dollars the government could accumulate; and its domestic interest rate came under control of its central bank.

At the time of the 2001 crisis, the government realised it had to adopt a domestically-oriented growth strategy. One of the first policy initiatives taken by newly elected President Kirchner was a massive job creation program that guaranteed employment for poor heads of households. Within four months, the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar (Head of Households Plan) had created jobs for 2 million participants which was around 13 per cent of the labour force. This not only helped to quell social unrest by providing income to Argentina’s poorest families, but it also put the economy on the road to recovery.

A key Argentine government official (advising the Minister of Employment) who was instrumental in the implementation of the Head of Households Plan had earlier attended a Conference in Chicago in 1998 and attended a session where Randy and myself presented papers outlining the way in which a Job Guarantee would operate and provide macroeconomic stability. We have stayed in touch ever since.

Conservative estimates of the multiplier effect of the increased spending by Jefes workers are that it added a boost of more than 2.5 per cent of GDP. In addition, the program provided needed services and new public infrastructure that encouraged additional private sector spending. Without the flexibility provided by a sovereign, floating, currency, the government would not have been able to promise such a job guarantee.

Argentina demonstrated something that the World’s financial masters didn’t want anyone to know about. That a country with huge foreign debt obligations can default successfully and enjoy renewed fortune based on domestic employment growth strategies and more inclusive welfare policies without an IMF austerity program being needed.

The clear lesson is that sovereign governments are not necessarily at the hostage of global financial markets. They can steer a strong recovery path based on domestically-orientated policies – such as the introduction of a Job Guarantee, which directly benefit the population by insulating the most disadvantaged workers from the devastation that recession brings.

In February 2012, the Greek government bowed to Troika pressure and agreed to cut the adult minimum wage of 751 euros per month by 22 per cent. If they increased the minimum wage a bit as well as reversing the 22 per cent cuts and then offered employment to anyone who wanted a job at that rate, then the boost to aggregate demand would be significant.

By pegging a currency to another, guaranteeing convertibility and then allowing the financial sector to “dollarise” your economy (drown it in foreign currency-denominated debt) – is a sure way to force a country into financial ruin or more or less permanent austerity.

Please read my blog – Why pander to financial markets – for more discussion on this point.

As noted above, prior to the crisis in the early 2000s, the Argentinean Peso was pegged to the US Dollar (1:1), in January 2002, the government finally realised that they could no longer maintain that peg and the currency began to depreciate and rose to nearly 4:1 by mid-2002. It stabilised at that rate and then slowly appreciated again until it reached a value of around 3:1 which was sustained for the next 6 or so years. More recently it has depreciated somewhat

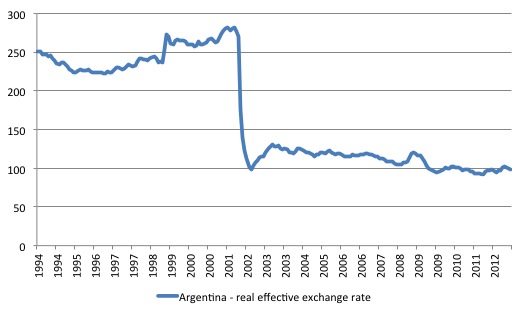

The Bank of International Settlements publish monthly Effective exchange rate indices – for 61 countries from January 1994.

You can learn about this data from their publication – The new BIS effective exchange rate indices – which appeared in the BIS Quarterly Review, March 2006.

There was an earlier publication – Measuring international price and cost competitiveness – which appeared in the BIS Economic Papers, No 39, November 1993.

Real effective exchange rates provide a measure on international competitiveness and are based on information pertaining movements in relative prices and costs, expressed in a common currency. Economists started computing effective exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because that ended the “simple bilateral dollar rate” (Source).

The BIS say that:

An effective exchange rate (EER) provides a better indicator of the macroeconomic effects of exchange rates than any single bilateral rate. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is an index of some weighted average of bilateral exchange rates. A real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted by some measure of relative prices or costs; changes in the REER thus take into account both nominal exchange rate developments and the inflation differential vis-à-vis trading partners. In both policy and market analysis, EERs serve various purposes: as a measure of international competitiveness, as components of monetary/financial conditions indices, as a gauge of the transmission of external shocks, as an intermediate target for monetary policy or as an operational target.2 Therefore, accurate measures of EERs are essential for both policymakers and market participants.

If the REER rises, then we conclude that the nation is less internationally competitive and vice-versa.

The following graph shows the REER from January 1994 to October 2012.

It peaked in October 2001, just before the crisis really began and by January 2002 it had fallen to 62.1 (Indexed at 100 as at October 2001). The low point came in June 2002 (index number was 34.8), after which it rose and stabilised around 45. It certainly depreciated but with it came a massive boost to international competitiveness.

The depreciation created a major change in the trade sector. Argentine exports became much cheaper and demand grew rapidly at the same time as import demand fell because of the rise in prices in the newly restored local currency.

It also turned out that the rise in China helped Argentina via soya bean exports which helped stabilise the currency. In general agriculture started booming.

The Government also sought to take advantage of the massive shift in relative prices (terms of trade) by providing incentives for import substitution. The tourism industry also grew rapidly as a result of the currency depreciation.

Before too long, the peso started appreciating again but by then the economy was on a solid growth footing with strong social welfare spending to maintain domestically-sourced growth and a booming export sector.

In the mid-2000s the Government actually had to take measures to stop the peso appreciating further given the size of its trade surplus. The central bank acquired huge stockpiles of foreign reserves (USDs mainly) by selling pesos in the foreign exchange market. The exchange rate is now relative stable at the higher value.

The foreign exchange intervention of the central bank (selling pesos) is sterilised by issuing government debt which is a quite different operation to the current ECB claims that it is sterilising its SMP. But that is another issue again.

While the Greeks do not have large quantities of natural resources like Argentina did when it defaulted and floated in 2001-02 it still has very desirable assets that are exchange rate sensitive – its tourism capacity (and its ship-building industry). I predict that there would be a boom in tourism virtually immediately and investment funds would flow into it.

The change in the current account would put a floor into the currency fall.

But in the meantime there would be a risk of inflation coming through the current account – as import prices rose in domestic-currency terms. As the currency appreciated again (as the Germans flooded into the sunny Greek islands to escape the Berlin winter) the inflation risk would be attenuated.

The Greek government would be advised to “discount” cost of living adjustments in their pension and wages system in this context. The exchange rate will not fall for very long – it would be a sharp, once-off adjustment spread out over a few months before stabilising.

This means that there is a real income loss to the nation (via the higher import prices) and that must be borne. Attempting to adjust nominal returns within the nation for these losses would create the danger of an inflationary spiral.

But as long as real productive capacity can be brought into use via public spending the danger of hyperinflation is low in these circumstances.

Would Greece need to impose capital controls? It is likely that the Greek government would require some strict capital controls. Malaysia gained major benefits from adopting this strategy in 1997. The IMF has now demonstrated the conditions under which capital controls, previously eschewed by free market ideologues, can be highly beneficial to a nation making large currency adjustments. Greece would fall into this sample.

Please read my blog – Are capital controls the answer? – for more discussion on this point and the reference to the IMF report that argued in favour of capital controls in selected circumstances.

None of these adjustments would be easy and costless. But once the nation has its currency sovereignty restored the national government would be able to spend, in a strategic way, to increase domestic production and employment and kick-start the growth process.

It will still have to ensure that its nominal pension system (which is relatively generous by world standards) is capable of being maintained in real terms. That is, it is likely that some structural changes to entitlements will be needed (read: cuts) to ensure that the productive capacity of the economy is in line with the nominal demands on it.

Greece’s inflation history in the past indicates that this sort of policy change will be required. But it would be far better to pursue that course of action within a growth environment supported by its own currency.

Trying to impose harsh structural adjustments when there is a major cyclical event (recession) occurring is very difficult (politically) and highly damaging (economically and socially).

Argentina grew very strongly within two years of its crisis.

The economy dived into a deep recession from December 1998 and then endured 17 successive quarters of negative growth culminating in the real output free fall in the year starting with the December 2001 quarter (-10.5 per cent), March 2002 (-16.3 per cent), June 2002 (-13.5 per cent), and September 2002 (-9.8 per cent).

Once they abandoned the peg and concentrated on domestic policy (and job creation) they began growing again robustly in the first quarter 2003 and continued that pattern for several years until they became caught up in the current global crisis.

During the current world crisis Argentina endured a very modest recession (contracting -0.8 per cent in the June quarter 2009 and -0.3 per cent in the September quarter 2009 – before bouncing back to fairly robust growth.

After the default and float, the economy grew at an average growth rate of 8.4 per cent through to the current period. Argentina’s experience tells us that Greece could resume growth next year if it defaulted and re-introduced its own currency.

Conclusion

I have to run now to my workshops and meetings.

No-one is denying that the Greek economy has structural issues which predicate it to imported inflation. Even with the harsh fiscal austerity which has seen its unemployment rate rise to above 25per cent with no ceiling in sight, the current account deficit has risen.

Its export base is narrow and it imports a wide variety of consumer goods including food.

But those problems are not going to be solved more quickly by impoverishing the nation. A freely floating exchange rate will be a more effective way of attenuating the imbalances that have emerged between northern and southern Europe with respect to trade.

However, the real bonus that an exit would bring is that the Greek government could unambiguously concentrate on a domestic growth strategy and put an end to its recession.

The last four years have brought the need for some reforms – to the taxation and pension system – into relief. Within a growth context, the Greek government would probably have a better change of brokering these changes with its population than under the current conditions which are fermenting total social breakdown and open rebellion.

Argentina does provide some guidance to what happens in these situations and the message, while complex and structured, is overall that Greece would be better off defaulting and reintroducing a floating currency.

The crisis in Argentina was very damaging and the poverty rates rose alarmingly. But the predictions of the mainstream economists (especially from the IMF) at the time did not come to fruition and an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) can help us understand why.

The nation was able to kick start growth very quickly by abandoning the peg and concentrating social spending in the domestic economy.

It had to default on its foreign debt (in US dollars) to achieve that change of policy focus. It also made the most of the increased competitiveness as a result of the massive depreciation by providing incentives for import substitution and renewed export performance. There was a burst of inflation but that fell rapidly and has stabilised as the currency appreciated again.

My advice to any government (when I am asked) is the same advice that applied in the Argentine case.

First, restore currency sovereignty by using a local currency that the elected national government issues under monopoly conditions.

Second, abandon any currency pegs.

Third, re-negotiate all foreign-currency debts into local currency units. If that is not acceptable to the counter-parties then default.

Fourth, concentrate the new-found fiscal freedom on domestic job creation to stabilise incomes and provide the jumping board for growth.

Fifth, take advantage of the currency depreciation to provide incentives for import-competing and exporting industries.

The road is a rocky one for sure but better than years of suffering from austerity. There is no real way out of that path.

I might struggle to write a blog tomorrow – although I have some data I am looking at which is interesting. I have a full day of workshops and meetings to attend to and then an overnight flight back to Sydney, then another 4 hour flight back to Darwin. I also want to go for a long run around Namsan Park in Seoul before work tomorrow morning. The Park provides beautiful views of this massive city (and I get my fitness fix). But we will see.

This morning I was confined to the “Executive Fitness Room” at the hotel running the treadmill for an hour. So I need some fresh (albeit damp and cold) air tomorrow morning.

I’ve started humming the Beach Boys’ song – I Get Around – to myself lately!

At any rate – that is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Extract from, (footnote) Global European Anticipation Bulletin

“15 As we had anticipated and contrary to the prevailing discussions on the end of the Euro, the exit of Greece… and other madness

which proves, if it were still needed, that the economists and other experts of this craft, should really develop their multidisciplinary

knowledge in particular in politics, geopolitics, forecasting and the working of networks and complex systems. They could also

usefully stop “barking” for more or less concealed financial economic interests. It’s not only in the sphere of health and drug testing

that conflicts of interests are frequent. Last remark on this subject: to continue to give the Nobel Prize for economics to American

specialists, as has just been done again, is frankly proof that the whole discipline is blind. The current crisis marks the complete

failure of prevailing economic thinking since 1945 and nevertheless one continues to validate the work from universities and experts

who have not stopped being wrong for over 60 years. Can one imagine such a situation in physics, in chemistry, …? Rewarding

scientists who never produce results? That illustrates at what point it’s really a Nobel Prize for ideology like that for peace (Obama,

EU,…).”

Bill is as always completely ignoring how deeply integrated Greece is in the European Union .

The yearly fiscal transfers from the EU budget are measured in percentage points of its GDP, and those funds go into highly sensible sectors of the Greek economy, like for instance infrastructure investment through the regional cohesion funds or the agricultural subventions through the common agricultural policy. On top of that, Greece few exports are concentrated in the European Union, where they do benefit from no trade barriers, protected trademarks in traditional products and so on and so forth.

Ah, but I hear you say – exiting the Eurozone is not the same as exiting the European Union! Why can’t Greece have its cake and eat it too? They could, of course, but then again, why should the rest of the EU countries accept a unilateral and complete default on Greece’s Euro-denominated debt, while at the same time maintaining all its privileges? The fact of the matter is that the European Union in general and the Eurozone countries in particular can exert a far larger pressure on Greece than the rest of the world could on Argentina – and this is why a sovereign currency Greece won’t be able to do whatever it wants with its current debts.

Also, I wouldn’t put all too much hope in German tourists escaping “Berlin winter” for the “sunny Greek islands” right away – Greece has suffered from heavy competition from Turkey in the last decade, so much so that people interested in cheap tours (and the giant tourism agencies that serve them) have already switched in huge numbers to going there, because not only it is cheaper, the overall quality is nowadays better too. A return to drachma might make the prices fall again to a competitive level, but repairing their image and quality problem will be a multi-year struggle, and besides that Turkey will be able to counter-act most of Greece’s maneuvers too – they don’t want to lose the tourists they gained.

Not to mention the fact that the mass protests and strikes which have wreaked so much havoc in the Greek tourism in the last couple of years will not abate after the Euro-exit. In fact, I am willing to bet they will be even worse for the first months, maybe even years, once the greeks begin to feel what it means for a country which imports more than 60% of its energy consumption to have a falling currency with double digit inflation.

It must be nice to be a German and so sure of absolutely EVERYTHING !!

“For 2007-13, Greece has been allocated €20.4 billion in total Cohesion Policy funding”

source: “European Cohesion Policy in Greece” downloaded from “ec.europa.eu”

According to Eurostat cited by Wikipedia, nominal GDP was in 2011 €215.088 billion

It is obvious that cohesion funding is less than 2% of the GDP (about 1.6%). I would doubt whether they will get more during the next EU “пятилетка” (I meant an equivalent of the 5 years Soviet economic plan) and whether they still can rely on these funds when Golden Dawn finally seizes power. There is a plenty of strings attached…

It is highly debatable whether other countries belonging to EU would impose trade bariers in Greece after the default or make any serious attempts to seize assets belonging to Greek state. This is all dirty politics. Greece can always exit NATO and then rent a naval base or two to Russia in exchange for cheaper energy and security guarantees against a possible Turkish invasion (just like Armenia). Considering the likely evacuation of the Russian base in Tartus this would be a very valuable asset and could lead to the restoration of Russian influence in the Balcans. That’s why nobody would allow for this scenario to unfold, just like with Iceland, when they mentioned asking Russia for help, everything suddenly changed…

(“When Iceland announced it was seeking a $6bn (£4bn) loan from Russia to help rescue its crisis-ravaged economy, some in the NATO alliance, of which Iceland is a member, took fright.” – BBC Thursday, 13 November 2008)

I don’t know, poor Greeks will most likely stay in the EU and suffer because the reasoning presented by Andrei prevails and because all the relevant Greek officers have been trained in Moscow (sorry, I keep mixing up, in West Point) but let’s wait and see…

“They could, of course, but then again, why should the rest of the EU countries accept a unilateral and complete default on Greece’s Euro-denominated debt, while at the same time maintaining all its privileges?”

Because the EU has export led policies and export led economics.

The EU could of course turn around and put up trade barriers to Greek exports in a fit of spite, but to do that would invite a similar response from the Greeks. Not to mention putting the EU in the dock at the World Trade Organisation.

And if the Greeks have the Drachma they can deal with that. The Eurozone cannot because it does not have fiscal flexibility.

The European Union is essentially neutral to its members in trade terms. It neither benefits them not disadvantages them. The so called benefits are much over trumped in an era of much easier global trade.

A nimble smaller country could very easily punch above its own weight. The problem the Greeks have is that they have historically had poor government.

You may say that the Greek economy is not that important to the EU. In that case it is small enough to be able to work with other Global players. I’m pretty certain that if the EU takes its ball home, then the Chinese and Russians will be very happy to help out.

Dear Bill

In addition to converting its debt to drachma’s, the Greek government should impose a moratorium on debt servicing for 3 years. After that, they can negotiate with their creditors. Since the Greek government would not be able to borrow anything but has a large primary deficit, which will grow as a result of expansionary fiscal policy, inflation is quite likely. However, better to have inflation than 25% unemployment.

Regards. James

IRELAND “doesn’t get a gig in the Report” because it’s what’s called the teachers’ pet. Or, as Bill calls her, the “poster child” of the Eurozone. No badmouthing IRELAND, if we can help it.

Vassilis,

The teacher’s pet isn’t supposed to get treated badly! It’d be more accurate to say that Ireland is in an abusive relationship with the IMF/ECB. We just know they’ll change some day……

Bill’s description of the intellectual poverty of the economic “modelling” company he interviewed with sounds right. There is a lot of duplicty in business and managerial economics. A lot of cowboys just make stuff up to suit themselves. Their laughter showed they knew it was a joke but they didn’t care. The joke was on the public and the modelling company was being paid (presumably) by its neocon backers. The whole thing was snake oil and a confidence trick; a very common phenomenon in “high finance”.

I would like to see you debating with Yanis Varoufakis – I don’t buy his argument that Greece is toast outside the Euro.

Its toast withen its cage for sure with massive capital destruction such as the Greek railways “debacle ? / shutdown when it has a major oil balance of trade problem.

Its a force feed them BMWs medicine although to be fair countries like Ireland & Greece do not buy too many BMWs anymore.

Our function it seems is to keep the cost of German capital down so that they can continue to supply the Anglos with BMWs…….

The UK / German trade is getting very weird.

Adam (ak) wrote:

No it isn’t, because the structural and cohesion funds are not the only funds that member countries receive from the European Union. For instance, there are the common agricultural policy funds, which make an even larger part of the EU Budget.

The simplest way to get a picture of the net contribution of EU funds to the economy of a specific member country is to look at the EU Budget reports, like the Financial Report 2011, and see the operational balance between expenditure and revenue to and from the EU Budget, specifically described in that document under Annex 2C (Page 102).

Greece receives constantly a surpluss of anywhere from 3 to more than 5 Billion € every year, which is procentually between 1.6% and up to 3.3% of the GNI (2.2% in 2011), with the long term average for the 2000-2011 period of well over 2%.

On the other hand, if it ends up a matter of geopolitical maneuvering, the European Union has far more pressure means on Greece than the other way around – a growing Russian influence in Greece would be annoying to be sure, but on the other hand the European Union might begin to stop taking Greece’s side in the matter of the name of the Republic of Macedonia. In fact, it might take a fast track of EU Membership for the entirety of the former Yugoslavian countries, making sure that whatever russian influence that would be growing in Greece would be well contained all around by much more EU friendly new member states.

If this is not enough, Turkey’s accession process to the European Union might suddenly find itself moved from being frozen to a fast track as well – and Greece would be the small, and comparatively insignificant country that moves away from the EU, while its traditional enemy would become the big, important country that is the EU new poster child. And the EU might find itself suddenly siding with Turkey on the matter of Cyprus as well, cause, hey, we are new best friends then, right? All that would have much more devastating consequences to Greece than the “advantages” that come from becoming a banana republic for Russia. In fact, I would argue that Russia will probably have no interest to help Greece significantly while at the same time going above and beyond political posturing against the EU – after all, the EU is Russia’s main trade partner, with more than 50% of its trade volume.

But this is all pretty offtopic, and far-fetched to boot. I for one think it would not have to reach anywhere near this escalation – it would be sufficient for the rest of the European Union to just suspend the EU Budget payments and if need be exclude Greece from being part of the free trade union and/or to restrict freedom of movement in order to control what an non-Euro Greece would do with its debt. Mind you, not that I think we would actually do that – for humanitarian reasons and for the sake of being able to sing kumbaya together, the other member states would probably in the end cave in and not impose any particularly tough sanctions , for the sake of the

childreninnocents. Though of course innocence is a matter of perspective isn’t it – how many innocents are there left, if everybody keeps electing the same incompetent cliques to govern them into ruin and at the same time keeps taking advantage and part of the pervasive corruption that permeates every level of the Greek economy & society?Neil Wilson says:

Yet the EU17 hovers historically around a more or less neutral balance of trade (slightly negative in the long term average) while the EU27 has a pretty clear negative trade balances with the rest of the world, with the intra-EU trade making up in both cases a far larger part of their economies. So what exactly are you talking about? In fact, if we were to exclude the one or two outliers – Germany with its indeed export led economy, maybe Ireland with its tax haven economy- the extra-EU trade Balance would be pretty severly in the minus.

Given the balance of trade between the EU and Greece, the effect of re-introducing custom duties between them would mean from the perspective of EU a negligble if at all measurable effect, while from the perspective of Greece would mean losing a free trade agreement with their by far main trade Export market.

Also, there would be no need for “trade barriers” per se above and beyond normal custom duties applied to imports from outside the EU, so there would be absolutely no reason for the WTO to get involved in anything. Normal custom duties, combined with the suspension of special protection rights for historical trademarks and the stopping of subventions from the EU Budget to Greece would be more than enough to heavily damage their economy, especially the few export-oriented branches that still exist.

You might say this will be compensated by re-calibrating their export to other trade zones outside of the EU, but if that were so simple, the question becomes why Greece has not managed to do so up till now – there is a very interesting recent working paper from the IMF about how a significant part of why the southern economies are doing so badly today is not (just) because of the evils of the Euro, rather also because they completely missed expanding their trade (specifically their exports) in the emerging markets, like the BRIC.

Sure, a overvalued currency compared to their productivity hurt them, but this is in many sectors more than compensated currently by receiving heavy subventions from the EU (like the agricultural sector) – with a heavily devalued drachma they will be able to lower prices, but they might also lose the subventions, making it a pretty null sum game.

Bill puts his hopes in tourism, but even ignoring the immediate difficulties in terms of image and competition that Greece has, it would be enough for the EU to restrict the participation of Greece to the free movement zone as well, i.e. reintroduce visas, which will probably end up escalating to all EU citizens requiring visas for going to Greece, which, no matter how much of a small formality that would be, would be enough to make Greece that much less interesting as a destination.

Again, not that I believe it would end up anywhere near this conflict level or such drastic measures, but it is naive to think that the deep integration of the Greek economy within the EU would not be a obstacle in the way of Greece doing whatever it wants in regards to its Euro-denominated debts.

In a country that has to import two thirds of the energy it consumes, “dealing with that” through currency devaluation will have enormous direct and immediate negative consequences on their own economy and standard of living. Not to mention that of course high energy costs will make in turn energy-intensive industries, like for instance cement and other building materials, one of the main exports of Greece, that much more expensive in real terms on the Export market as well, severly limiting the positive effects of a devaluating currency.

Perhaps, but I doubt becoming a dependant on Russia or China is a desirable outcome for any sane country currently.