I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

Employment guarantees should be unconditional and demand-driven

There was an interesting paper published by the World Bank (March 1, 2012) – Does India’s employment guarantee scheme guarantee employment? – which offers some insights into how the Indian employment guarantee works. I thought it was an odd title because by definition the NREGA scheme is an employment guarantee. The relevant issue is a guarantee to whom. The World Bank research confirms the outcomes of my own work on the Indian scheme that it’s conditionality reduces its effectiveness. Those who gain jobs benefit but there is a shortage of jobs on offer relative to the demand for them. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) shows that an unconditional, demand-driven employment guarantee, run as an automatic stabiliser, is the most superior buffer stock approach to price stability. Conditional (supply-driven) approaches not only undermine the job creating potential but also reduce the capacity of the scheme to act as a nominal anchor.

I discuss the concept of a Job Guarantee in considerable detail in this blog – When is a job guarantee a Job Guarantee? . Essentially, as developed within Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), the Job Guarantee comprises an unconditional and universal job offer at the minimum wage (calibrated to be an inclusive living wage) to anyone who wants a job. It would mostly eliminate unemployment (except frictional) and probably eliminate underemployment.

The reality is the Job Guarantee approach is the only guaranteed way that the national government can ensure there are enough jobs available at all times without activating an inflationary spiral. It is a very modest approach given those aims – choosing to work via the automatic stabilisers.

The NREGA was considered by the Economist article (November 5, 2009)- Faring well – where they noted that “India’s grand experiment with public works enjoys a moment in the sun”.

The experiment they were referring to is the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), which was re-named the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) in 2009.

The Scheme guarantees 100 days of minimum-wage employment on public works to every rural household that asks for it. The adults must be willing to undertake unskilled manual labour a the legal minimum wage. Once an adult applies for work, the scheme must employ them within 15 days or pay unemployment benefits.

Local communities have input into the selection and design of the jobs and local government plans and implements the work activities.

The Indian Government maintains a wonderful NREGA Home Page with a wealth of information available.

The Economist article noted some administrative issues associated with the NREGA scheme but concluded that:

Despite such flaws, the NREGA is winning praise from unexpected quarters. One reason India weathered the financial crisis of the past year was the strength of rural demand, many economists argue, and one reason for that strength was the expansion of the act to every rural district in April 2008. Once dismissed as a reckless fiscal sop, the scheme is now lauded as a timely fiscal stimulus. Because it must accommodate anyone who demands work, it can expand naturally as the need arises.

Poverty reduction

The World Bank article says that in introducing this MGNREGS “India embarked on an ambitious attempt to fight rural poverty.” They consider the ways in which the scheme fights poverty:

1. Direct employment and income guarantee to poor rural areas.

2. Poor people will leave the scheme only when something better arises and non-poor will not seek to access it.

3. The minimum wage becomes binding for all casual work whether in the scheme or not. It thus “can radically alter the bargaining power of poor men and women in the labor market”.

4. It “can help underpin otherwise risky investments” because “(e)ven those who do not normally need such work can benefit from knowing it is available”.

In my 2008 book with Joan Muysken Full employment abandoned we wrote (p.255) that the NREGA was designed “to bridge the vast rural-urban income disparities inequality that have emerged as India’s information technology service sector has boomed”.

Was it an anti-poverty scheme as the World Bank Report suggests? Answer: Yes but it was designed to accomplish other aims.

The problem faced by the Indian government was that there was too much migration from the poor rural areas into the burgeoning urban areas. They decided, sensibly, to reduce the incentive for the migration by creating work and lifting standards of living in the rural areas.

The scheme, despite its shortcomings (see below) has been very successful and millions of jobs have been created and a noticeable dent in poverty has occurred.

Wages paid sometimes exceed the going private sector wage and this has led to complaints from employers who want to pay below what effectively becomes the minimum wage.

In my work I did for the ILO in 2008-09, evaluating the South African Expanded Public Works Programme and designing a minimum wage framework for the scheme (and hence the economy as a whole), the same issue was continually raised by those opposed to the Scheme.

I noted in my Report:

First, the aim of the South African government is to significantly reduce unemployment and to eliminate absolute poverty and also provide for an improved personal capacity to manage risk via savings (that is, reducing relative poverty). The proposal to increase the minimum EPWP wage is consistent with that overriding objective. However, maintaining sectors in the private labour market that pay “poverty wages” is not consistent with that policy. It in the interests of the South African economy that higher productivity employment is fostered rather than relying on low-wage, working poor jobs to absorb the unskilled labour force.

Second, the EPWP can serve an industry policy to promote a quickening of this move to a high-wage, high productivity economy by placing pressure on market economy employers through the wage floor it establishes

At the time, I argued that if the EPWP wage became the national minimum then both demand and supply effects would be present. Employers currently paying below the wage would be confronted with the decision of operating that new legal minimum or closing down. What happened to the workers who lost their jobs depends on how many EPWP jobs were created and the impact of the higher wages on spending and overall job creation. There would also be a dynamic present to restructure existing employment.

If the EPWP was scaled up into an unconditional wage offer to anyone who wants a jobs (which we recommend) then the supply effects are likely to be significant.

In this latter context, employers paying below the proposed minimum would start to find it difficult to attract labour as the EPWP jobs (being always available, local and better paid) would become far better alternatives to the available labour. The employers would then be forced to invest in productive capital to increase the productivity of labour and pay at least proposed minimum per month to retain labour.

There may be some cases where a worker would agree to working below that if the job provided them with other non-pecuniary rewards that compensated. It is unlikely that all the workers who are currently earning below proposed minumum per month would be attracted to the EPWP.

If the EPWP minimum wage became the statutory minimum in South Africa, it is clear that this is the most desirable way in which to introduce and sustain a national employment guarantee system, then the private sector employers would face an immediate need to restructure their workplaces (invest in higher quality capital) to meet the new legal minimum wage levels but more importantly to stop the migration of their labour forces to more attractive EPWP employment.

Some employers would close their operations because they would not be able to operate at the higher costs. Economic development always involves a movement from lower productivity-higher cost production to higher productivity-lower cost production.

The ability of the EPWP to absorb this displaced labour would depend, in turn, on its scale. If there was a true EPWP safety net operating then these closures would shift workers into higher income areas and represent an improvement. That is the rationale of using the EPWP as a quasi-industry policy which can stimulate the South African economy towards the desirable high-wage, high productivity growth path.

The World Bank article examines the concerns expressed by opponents of the Scheme that the “the wage rate on MGNREGS is being set too high, relative to actual casual labor market wages” are unfounded.

In fact, “for India as a whole the two wages are quite close”.

Jobs versus cash handouts

The Economist article then makes an interesting point:

Policy wonks argue that cash handouts to the poor would be easier to administer, and would leave the recipients free to work the fields or roll beedis for private employers. But the poor themselves seem surprisingly sceptical of such an idea. “If money comes for free, it will never stay with us,” one elderly farmer says. “The men will drink it.” To wring anything out of India’s calcified bureaucracy takes a fight. If people feel they have earned their money from the government, they become more determined to claim it, even if that means waiting all day outside the village bank.

Mainstream economists always think cash handouts are better way of solving income insecurity because it allows the recipient to choose and it is always assumed that the individual knows best. The problems with this conception are manifest. The most obvious one noted in the quotation above is that individuals do not hunt alone. They tend to have families and have to assume wider responsibilities.

So often more enlightened policy advocates will argue that “in-kind” transfers are better – because at least the children will be fed! The NREGA is a twist on that theme and raises another very important point.

The “in-kind” component is the job. And it works to get “food on the table” instead of “grog down the throat” because people intrinsically value their involvement in productive work. There is a sense of achievement in earning one’s living.

Mainstream economics textbooks have labour-leisure choice models to determine labour supply. Labour is a bad and hence undesirable, leisure is a good. The only way you will engage in a bad is if you are paid. But this extremely blinkered view of the world that mainstream economists have reflects their ignorance of work in other social sciences. Economists have one of the worst records as a discipline in cross-citations of other disciplines. They just think they know everything – and end up knowing nothing much at all.

Other disciplines (sociology and psychology, for example) reveal that work is seen as desirable (rather than a bad) and the value of it extends far beyond the wage earned. That is one the reasons I always advocate creating jobs rather than paying basic income guarantees or other forms of income support.

Conditionality

The NREGA is a cut-down partial Job Guarantee, in the sense, that the latter is unconditional and demand-driven (that is, the government employs at a fixed price up to the last person who seeks work) whereas the NREGA is conditional and supply-driven (that is, the government rations the scheme according to some rules – number of jobs, hours of work or some other rationing device).

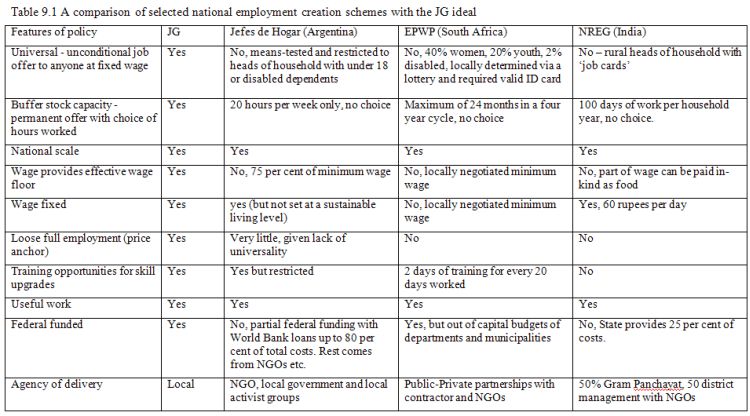

The following Table is taken from Full employment abandoned (Table 9.1, p.257) and compares the ideal Job Guarantee with the partial schemes introduced in South Africa (EPWP), Argentina (Jefes) and the NREGA in India. You can readily appreciate that the underlying modern monetary theory (MMT) which drives the JG conception is missing from the other schemes.

For example, in the NREGA sub-national governments, which are revenue-constrained, contribute to the investment outlays of the scheme. Further, the scheme is not universal nor unconditional. Nor does it provide a permanent job offer which means there is no “buffer stocks” capacity available in India.

Also, given the wage arrangements (some of the wage can be paid in food) the NREGA does not provide a comprehensive nominal price anchor. By paying a minimum wage to all workers, the JG creates what we call “loose full employment” – in the sense it places no pressures on the price level in its own right. It can also be used to discipline the inflation process by redistributing workers to the fixed price sector. There is no such capacity in NREGA.

Finally, NREGA provides no training capacity. The ideal JG would integrate skills development into the unconditional job offer and thus build dynamic efficiencies into the economy and provide the least-advantaged workers income security but a ladder to move to higher productivity jobs in the future.

The World Bank article considers this issue in some detail. The authors say:

The idea of an ―employment guarantee‖ is clearly important to realizing the full benefits of such a scheme. The gains depend heavily on the scheme’s ability to accommodate the supply of work to the demand. That is not going to be easy, given that it requires an open-ended public spending commitment; similarly to an insurance company, the government must pay up when shocks hit. This kind of uncertainty about disbursements in risky environments would be a challenge for any government at any level of economic development.

If the maximum level of spending on the scheme by the center is exogenously fixed for budget planning purposes then rationing may well be unavoidable at any socially acceptable wage rate. Or, to put the point slightly differently, the implied wage rate-given the supply of labor to the scheme and the budget-may be too low to be socially acceptable, with rationing deemed (implicitly) to be the preferred outcome.

They consider a simple model aimed at assessing the performance of MGNREGS “in meeting the demand for work across states”. They note that the adminstrative data available from the Scheme (available from the link I provided above) shows that “52.865 million households in India demanded work in 2009/10, and 99.4% (52.53 million) were provided work”.

They say the such a claim “demand”” is unlikely to reflect true demand for work because there were administrative disincentives for states to provide a full reckoning of “excess demand” and other processes were likely to reduce the demand for work (ignorance, officials discouraging certain cohorts).

These are well-known problems with the Scheme but do not detract from the fact that in one financial year 52.8 million people were provided work.

To get a better estimate of “demand”, the World Bank authors used household survey data (“66th Round of the NSS for 2009/10 which included questions on participation and demand for work in MGNREGS”).

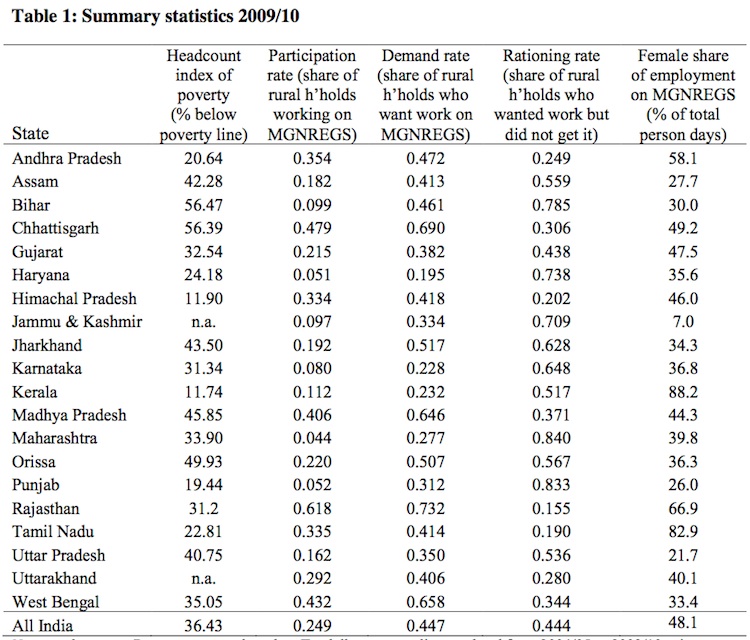

The following Table (taken from their Table 1) shows summary statistics for 2009-10 by Indian State. The Participation rate (%) is compared to the Demand rate (%) derived from the NSS data) to derive a so-called “Rationing Rate (%)” which is the extent to which unmet demand within the MGNREGS exists.

You can see that there are significant spatial disparities in the unmet demand (and the rationing rates). For the nation as a whole, PR = 0.249 while DR = 0447, given a RR of 0.444.

This means that 45 per cent of rural households in India desired a job under the scheme but only 56 per cent of them obtained work (100*PR/DR) which gives the rationing rate of 44 per cent (100-56).

The other point that the World Bank makes is that:

Participation rates in MGNREGS are only weakly correlated with the incidence of poverty across the states of India.

You can see that by assessing the first two columns of data in the Table. Relatedly, the “correlation between MGNREGS spending per capita and the poverty rate is -0.02 using spending in 2009/10 and 0.04 for 2010/11.”

The question then is “Why is MGNREGS not more active in poorer states?”. Note, first that the scheme wasn’t all about poverty targetting. It wanted to stop migration flows and the only way it could do that was to provide work in the rural areas.

But the question remains and we dealt with it in our 2008 book mentioned above. The World Bank article rehearses similar arguments which bear on the way the scheme is designed.

First, by forcing the states to share in the “budget” of the Scheme, the implementation is biased against poor states who are not as well endowed with available resources – given they are not currency issuers.

Second, the poorer states have less developed administrative capacity

Third, the poorest workers are “less empowered in poorer states”.

Conclusion

The overall conclusion is that the demand for the work in the Scheme is highest in poorer states, which is what we would expect.

But the World Bank research finds that:

… actual participation rates in the scheme are not (as a rule) any higher in poorer states where it is needed the most. The reason for this paradox lies in the differences in the extent to which the employment guarantee is honored. The answer to the question posed in our title is clearly ―no.

The problem with the MGNREGS is that is not an unconditional employment guarantee. Unless the government stands ready to offer work at the stated wage rate to all-comers then by definition it is not offering an employment guarantee.

By forcing non-currency issuing units within the nation (state and local governments) to share in the outlays required to render the Scheme operational, the Indian government is ensuring that rationing will occur. Under these circumstances, job creation becomes constrained by budget outlays.

Interestingly, the World Bank says that “despite the pervasive rationing we find, it is plain that the scheme is still reaching poor people and also reaching the scheduled tribes and backward castes.”

But once the “allocation of work through the local-level rationing” becomes a feature of the system it is obvious that there will be “many poor people who are not getting help because the employment guarantee is not in operation almost anywhere”.

The World Bank authors thus conclude that:

The first-order problem for MGNREGS is the level of un-met demand.

An open-ended guarantee is only viable if it is funded by the currency-issuer. It should be administered and operationalised locally but funded nationally.

Local communities, in liaison with their governments are best able to assess unmet community need which then defines productive avenues of work in the employment guarantee. But sub-national governmental units are always budget-constrained because, like households, they use the currency issued by the national government.

An effective employment guarantee has to be open-ended and unconditional. Governments think that large deficits are bad spend on a quantity rule – that is, allocate $x billiion – which they think is politically acceptable. It may not bear any relation to what is required to address the existing spending gap.

MMT shows you how it is far better to implement an employment guarantee by spending on a price rule. That is, the government just has to fix the price and “buy” whatever is available at that price (the employment guarantee wage) to ensure price stability.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

My thoughts on this are to separate out the ‘income provision’ from the ‘job provision’.

So the currency issuer purchases the spare labour at the determined rate using its issuing capacity. You then treat that as though you’ve bought a load of gold, or wheat or other commodity.

That ‘labour commodity’ is then given to the Executive to deploy as it sees fit.

It can then throw it away (effectively creating an Income Guarantee), or it can tax sufficiently to provide the infrastructure of the Job Guarantee and make sure there are sufficient jobs available to absorb the spare labour (on a structural basis), or the parliament can decide that provision of Jobs is a cyclical component the currency issuer element of government should be tasked with providing as well.

So the Guarantee of Income bit is cyclical spending, but the guarantee of Jobs has a cyclical and structural component for which there are political alternatives.

I thought Indian farmers are suiciding at record rates. Maybe that’s no longer the case. I wonder if a full JG would bring this horror to an end…

I am enjoying your blog but have a problem with the mmt analysis

absolutely agree European govts “balancing the books” is driving our continent into recession

and vital role of govt leverage (Q.U great idea) but cannot understand the analysis of horizontal transactions

a repeat of neo classical “netting out” of private loans

if the asset is created instantly and the liabilities destroyed over time this is not netting out

it is time dependent a dynamic model must be used

have more assets been created than liabilities destroyed over a period of time

it is possible for netting out over a time period but unlikely

leveraging is the norm until a debt fueled asset bubble pops

let’s try to step out of time let’s go till the end of time for our financial system

even if it lasts until the moon falls there would be a vast pool of liabilities waiting to be destroyed

even at the end of time there would be no netting out

the point is surely what effect in income and expenditure the loan has

take my own modest mortgage taken out 18 years ago luckily in a down time

I was instantly paying less mortgage than the rent I had been paying

now my repayments are 30% of comparable rent I will save over 8000 pounds this year

about 900000 over the 18 years I have not experianced a netting out of my loan in the round

There is rampant corruption in rural job guarantee scheme. Providing direct cash transfers to the people in need would reduce the oppurtunity for middle men/government servants from pocketing the money. For example see, http://www.indianexpress.com/news/corruption-in-nrega-cannot-be-ignored-sonia-gandhi/907023/

and

http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-03-22/jaipur/31224438_1_mgnrega-workers-social-audit-mazdoor-kishan-shakti-sangathan

Anybody interested in knowing the kind of exploitation that takes place in Indian villages should read the book by P. Sainath titled “Everybody loves a good draught”.

Regarding farmer suicides – Five States did manage a significant decline in the average number of farm suicides between 2003 and 2010. However, more States have reported increases over the same period. For details see – http://www.indiatogether.org/2011/dec/psa-suidata.htm

cheers,

Sriram

“…have more assets been created than liabilities destroyed over a period of time…”

No more net financial assets have been created.

Real asset creation must be a function of leverage.

What happens when the leverage loses it’s lever?

Paul we can measure over a period of time if more private assets have been created (with their future obligations for sure) which is leverage compared to past obligations being destroyed by paying back loans -deleveraging

surely as income increases over “most” time periods there is measurable private leverage

the netting out is an atemporal model

it is a bit like saying central bank printing money causes inflation because you can ignore the dynamic change in the amount of goods and services in the system

If new money is needed in the economy (and it is) then a universal bailout is justified on moral grounds alone because credit creation cheats both debtors and non-debtors and ultimately even the banks themselves though they are responsible.

Let the private sector provide jobs except for generous spending on legitimate infrastructure needs.

What is needed is government MONEY, not government jobs.

Dear Sriram (at 2012/06/25 at 21:21)

Thanks for your comment and information.

1. The rampant corruption is endemic to the community/society and not intrinsic to the policy per se

2. Are you suggesting that the millions that have been employed in the MGNREGS are not better off?

3. There is a dignity in work that cash transfers do not bestow.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

About this bit:

“Some employers would close their operations because they would not be able to operate at the higher costs. Economic development always involves a movement from lower productivity-higher cost production to higher productivity-lower cost production.”

Isn’t there a chance that this could potentially result in less private sector investment, at least in the short to medium term, rather than more?

Wouldn’t this also exacerbate inflationary pressures, due to a reduction in productive capacity?

After all, JG jobs tend not to add much to productive capacity themselves (as far as I can tell). If the higher minimum wage leads to businesses closing, this could mean a reduction in aggregate supply at a time when aggregate demand is increasing through the JG spending – leading to higher inflation. Could this be a problem?

Thanks.

F. Beard, but the private sector likes to employ people who are already at jobs. Employment scheme would provide those workers.

Employment scheme would provide those workers. PZ

Sounds fascist to me. Let the private sector provide its own job training programs.

Our problem is a fascist money system and the ill-distribution of money resulting therefrom.

Let’s keep our eyes on the true problem.

@y

If private businesses are forced to close because of JG it is because they are marginal businesses relying on low paid workers. In most cases these businesses would have local competitors providing alternative goods at higher prices. The competitors may have slack capacity or they may invest in additional capacity.

The workers laid off would either join a competitor or the JG, so there would be little change in net demand for goods and services. Any decreases in productive capacity would be soon be made up by the “market”.

@F Beard

The private sector prefers to rely on schools and colleges to train their workforce at the public expense. I can’t comprehend miserable life would get if we dropped universal education for private sector employment training.

@y

I also asked myself the question…What if goods and services provided by displaced marginal businesses are replaced by foreign products?

In that case there would be downward pressure on the nations currency making imports more expensive and exports more competitive. No doubt there would be some short to mid term inflationary pressures as Mr Market does his magic re-pricing work and the structure of the economy adapts.

So I guess there will be some inflationary pressure during the intitial process of change, but this will not spiral out of control and will reach stable equilibrium in due course.

There’s no getting away from the problem of lower cost labour in other countries, while global free trade is the prevailing policy. A country can either directly lower labour costs or let the floating exchange rate rebalance exports and imports. It seems far more sensible to let exchange rates do the heavy lifting. Keep everyone employed and maintain social cohesion as the structural changes in different countries play out. At least that way workers don’t get priced out of good produced in their own country thus destroying even more productive capacity.

I can’t comprehend miserable life would get if we dropped universal education for private sector employment training. Andrew

What about when robots are doing all the non-creative work? Will it not be obvious then that the true problem is unjust distribution of capital and not uneducated workers?

MMT does not yet grasp the fundamental injustice of credit creation – the means by which the so-called “credit worthy” loot everyone else.

@F Beard

My basic belief is in equality of opportunity and a more cooperative society. Fair reward for reasonable effort. I do not support an economic system where a small minority can own all the productive assets. Be it land, intellectual property or robots. At birth, we should have an equal opportunity to compete fairly and reasonably for an adequate share. Greed, monopoly and excess should be disincentivised. Honest but weak stragglers should helped along and encouraged by the strong. Sluggards need the boot. I also strongly support a healthy degree of diversity in lifetstyle, arts, sport, religion, sexual preference and the environment.

I recommend you drop in at Mike Norman economics to read what Roger Erickson says about modern money. I still think you have this obsessive notion money MUST be a irrefutable store of wealth. Nothing will disabuse you of this notion. It’s not that MMTers do not understand what money is.

In the current paradigm I would recommend to invest in assets if anyone desires to preserve the purchasing parity of their money. Then again, I would rather see a JG and healthy public pension scheme to promote income security and obviate the need for excessive saving.

Please read……10 points every citizen must understand about modern money.

“2) How currency is utilized.

Like all public services, currency use changes with context. In small populations with slowly adapting economies, commodity currencies may be a stable store of value. For large, dynamic economies, modern “fiat” currency is primarily a bookkeeping unit for denominating constantly changing transaction chains. The static value of dynamic modern currency must float, and is therefore negligible as a stable store of value. (note:b)”

oops….got carried away and drifted a bit off your point.

“MMT does not yet grasp the fundamental injustice of credit creation – the means by which the so-called “credit worthy” loot everyone else.”

I think MMT does get that. In fact, you have to believe in a false notion of banking operations not to get it. Warren is clear that banks are granted the privilege of a banking licence by the public and are abusing the privilege. Bill supports nationalising banks and putting credit creation to public purpose. Go read Michael Hudson and get a more in depth understanding of rent seeking behaviour. He follows MMT too.

Any decreases in productive capacity would be soon be made up by the “market”.

Now that’s wishful thinking.

Bill,

No, I am not suggesting that millions are not better off. In spite of many flaws in the way it is implemented, I support this program.

Cheers,

Sriram

I still think you have this obsessive notion money MUST be a irrefutable store of wealth. Andrew

Not at all. Where do you get that from? I advocate that common stock be used for private money. As for government money, fiat is the ONLY ethical money form. And fiat should simply be spent into existence and never borrowed by the issuing government.

Also, if the MMT folks grasp the injustice of credit creation, then where, besides Steve Keen, is their call for a universal bailout? Shall the victims be forced to earn their restitution via a JG? Isn’t that a bit lame, to say the least?

MamMoTh says:

Tuesday, June 26, 2012 at 11:02

Any decreases in productive capacity would be soon be made up by the “market”.

Now that’s wishful thinking.

It was partly a tounge in cheek comment, but not wrong within the context. Is it not a bit conceited to dismiss a basic premise of neo-classical micro-economic with the carefree whoosh of a hairy trunk?

Not at all. Where do you get that from?

Because you are constantly banging on about common stock as currency, full reserve banking and theft by creditors. From which I (perhaps erroneously) deduced was you being paranoid about the purchasing value of cash holdings. It is so similar to the kind of views being expressed very vocally on many comment threads by fearful pensioners on a fixed income.

Also, if the MMT folks grasp the injustice of credit creation, then where, besides Steve Keen, is their call for a universal bailout? Shall the victims be forced to earn their restitution via a JG? Isn’t that a bit lame, to say the least?

I can’t speak for any other MMT advocate. Calling for a universal bailout of debtors is fine for me. Far better than bailing out banks. For the MMT community to advocate it as part of a general macro economic theory might be a bit difficult though. MMT shows the same macro-economic objective could be achieved in a number of different ways. If I was trying to get MMT mainstream I would try to steer clear of specific economic prescriptions, even if I believed in the social justice of it.

i see the JG is a different case, as I see it the only viable policy in line with the stated macro objectives of maintaining price stability AND full employment.

I do not agree with your view on lots of issues. Not at all.

If you look at Europe the most noticeable thing is the massive inflow of capital. Capital? Yes, Humans through immigration. Yes, humans are the most valuable capital. Not worthless currency paper bills.

I would base my analysis on the presence of labour force instead of money supply as a force. If there is labour there is demand. If there is labour there is wealth being created.

To print money is to move around resources between people, it is much better to tax to reach that goal. But I know that higher taxes are not so popular (because it is to obvious what is going on) and it is more realistic for a politically and ideologically motivated economist to use the printing machine as the major solution to every identified problem.

Keep the money supply intact, import more labour and increase the velocity of money through increased production.

“Also, if the MMT folks grasp the injustice of credit creation, then where, besides Steve Keen, is their call for a universal bailout? ”

There are several ways to deal with the issue. The other is to ensure that people have enough money to pare down the debt *and* spend on goods and services.

Credit is not evil. It is the engine by which we get iPads and all the other good things in modern life. It’s when it is allowed to go Ponzi, funding non-productive investment, that you have a problem.

Correct regulation is the key, which may require a debt jubilee to reset the system. But after that you still need a Job Guarantee to deal with the fundamental paradox of productivity.

Credit is not evil. Neil Wilson

Sorry, but credit creation (as currently practised) is evil. “Loans create deposits” and the purchasing power of the new deposits comes from all other money holders without their permission and without adequate compensation (negative real interest rates). That’s theft.

It is the engine by which we get iPads and all the other good things in modern life. Neil Wilson

That’s a utilitarian argument. Credit creation also generates vast wealth and income disparity, enormous private debt and the boom-bust cycle (which is wasteful and dangerous in itself).

Moreover, credit creation is not the only means to consolidate real capital for economies of scale. Common stock as private money allows the same thing in an ethical, democratic (at least per share), decentralized, stable manner without usury, without the risk of deflation and without fractional reserves or a central bank.

You probably could finance the development of the iPad in the stock market, but you need credit to fund consumption

but you need credit to fund consumption MamMoTh

Or savings. Or borrowing of existing money. A universal bailout would enable debtors to pay down their debts and provide plenty of new money to non-debtors to use for consumption or honest lending. And if the bailout was combined with a ban on further credit creation then the bailout could be metered out to just replace existing credit debt as it is repaid for no net change to the total money supply (reserves + credit).

“That’s theft.”

I think we’ve had enough of ideologues over the last thirty years. There is no desire to replace them with another set of extreme beliefs.

Much better to address the evidence soberly and design systems based on that.

Well, if “Thou shalt not steal” sounds too extreme for you, the least we can do is eliminate all government support for credit creation such as deposit insurance, borrowing by government, a lender of last resort, legal tender laws for private debts, etc. The government itself, as the monopoly issuer of its own fiat, is the ideal institution to offer a risk-free storage and transaction service for that fiat that makes no loans and pays no interest. That service should be free up to certain limits. People could still use banks and credit unions but with the full knowledge that they were putting their money at risk.

While I certainly support some level of jubilee, mainly because I feel that without it we will NEVER mover forward, I certainly have some sympathy with the view that past obligations should be met. Most people who borrowed did so out of their own volition and saw the situation as workable in their current income to debt conditions. The insanity of the our current system is that once enough peoples income conditions changed (usually form no fault of their own…. they didnt “become” less productive) we dont provide adequate access to ways for people to work off their debts. I imagine that well over 90% of people would want to work off their debts as originally promised but too many cant find work!!

This is why I support a JG

F.Beard

I don’t think I understand your argument correctly. Credit is theft? Do you mean banks become a currency issuer of sorts by credit creation? Could you elaborate?

Lee Wang,

Yes, that’s the logic of “loans create deposits”. The new deposits dilute the value of old deposits. Purchasing power from the old deposits is thus stolen. Now some will argue that the “theft” is only temporary since the “repayment of loans destroys deposits” is also true. But how “temporary” is a 30 year mortgage? Also, Steve Keen points out that even a decline in credit creation will trigger a recession. There is thus a societal incentive to keep the total amount of credit ever increasing.

I do think you may have point here. But I can’t imagine it being that deposits get diluted. Money never dilutes, why would credit?

Any money creation (including temporary money – “credit”) dilutes the purchasing power of that money, at least temporarily and in the case of non-consumer goods it is more likely to be a permanent dilution. But of course, we must have money creation so the question then is “How can money be created ethically?” The solution is to separate government from banking and private money creation and to separate the private sector from government money creation. A monetarily sovereign government has no need for banks or private money since it can simply spend its fiat into existence and tax some of it out of existence. As for the private sector, it can surely come up with money solutions for the payment of private debts only without government privileges. Common stock is an example of a private money form.

As I said money doesn’t dilute. It’s a basic mistake to blame inflation on dilution of money. Well you could, but it only adds in the confusement, it’s easier to just consider aggregate demand and the production capacity. However I think you’re on to something. The government derives its power from its monopoly status as single issuer of currency. As long as it is accepted the government can spend all its likes(it could also do without acceptation, but you know what I mean). To keep money in demand, taxes are imposed as well as to regulate aggregate demand.

What you mean with dilution is that the government partially loses its monopoly power due to the creation of credit. It partially loses seignorage. However credit isn’t stable like money is(since their is no credit tax), so it leads to credit bubbles and instability. This would explain the completely ridiculous profits banks make, and the 2008 crisis.

The spending power (not spending, which is not limited) of a sovereign government is only limited by the productive capacity of everyone who uses their currency. Credit creation in effect would be the introduction of a new instable currency (because it is not taxed away). It would mean all credit is counterfeiting and yes that would mean it equals theft.

Fascinating stuff. I have to think a little more about this. Are you sure common stock would help though? And you support some kind of private debt? This seems counter to this point.

P.S. This also means countries outside of the US that accept dollars, actually materially support the US.

Are you sure common stock would help though? Lee Wang

I’m pretty sure it would for quite a few reasons:

1) Common stock as money requires no borrowing or lending. Assets and labor would simply be bought with new stock issue. Thus no PMs*, usury, or fractional reserves are required. This is a huge benefit since PMs, usury (see Deuteronomy 23:19-20) and fractional reserves are all problematic.

2) All price inflation is born by the owners of the issuing company since every receiver of the new common stock money is by definition a part owner of the issuing company. This is an important moral consideration.

3) Since all money holders are part owners of the issuing company then they could vote on how much new money is issued and for what purposes. Thus price inflation is under the control of only those affected by it.

4) The assets of the issuing company would typically be performing assets though PMs could easily be accommodated too.

5) Common stock as money shares wealth at the same times as it consolidates it for purposes of economies of scale. Labor problems should be non-existent since the workers would be paid in common stock and thus be part owners. The number of those with a stake in capitalism would increase. The need and desire for socialism should decrease.

Note*: PMs = precious metals. I know that it is silly to even mention PMs wrt money at this intelligent site but I used to deal with gold bugs a lot and the above points were written a few years ago.

And you support some kind of private debt? Lee Wang

I have no policy problem with the lending of existing money for interest since that is an actual (and voluntary) transfer of purchasing power, not the creation of new purchasing power at the expense of all other money holders as credit is.

Another benefit of common stock as money is that the amount of it would normally only increase so deflation would not be a problem. So there should be no boom-bust cycle caused by debt and its repayment. Of course, the common stock money should be redeemable for the goods and services of the issuing company but it is to be expected that the issuing company would recycle the common stock money into the economy in the form of wages and asset purchases.

What you mean with dilution is that the government partially loses its monopoly power due to the creation of credit. It partially loses seignorage. Lee Wang

That’s true too. For better or worse, credit is an alternative to fiat for the payment of private debts. And like you say, credit complicates the economy with boom-bust cycles.

As for “dilution”, I understand what you mean by aggregate demand and productive capacity but from an ETHICAL viewpoint dilution is the correct term.

“Any money creation (including temporary money – “credit”) dilutes the purchasing power of that money, at least temporarily and in the case of non-consumer goods it is more likely to be a permanent dilution”

Does it heck.

If I go to the barbers and have my hair cut paying with a credit card, then the expansion in output is instant and as a direct result of my credit use. That output *would not have happened* had I not used credit and would have been lost forever.

We have a service economy and flexible high response manufacturing systems. Credit is more likely to induce instant or near instant expanded output than it ever has in the history of man.

Yes but Neil that money doesn’t stay in the barber shop. It circulates and eventually reaches a bottleneck. The main bottleneck recently was the housing market. Most of the other potential consumer products/services bottlenecks were opened up by cheap foreign labour and global trade.

Regarding common stock. I see three problems, first the lack of sound information on business dynamics for most citizens, secondly the lack of division of management and labour. Sometimes it may be economically most efficient to employ more workers, this surely would have a downward pressure on the existing salaries of workers who are incentivized to vote against an expansion of the labour force. Third common stock seems to undermine the government monopoly on the currency.

Thank you for the clarification on dilution. Again regarding other countries using U.S. currency, would you agree they are effectively materially supporting the American state and undermining their own?

This has been an absolutely enlightening discussion. It’s all very complex though, I’ll need to think it over some more.

@Neil Wilson. It seems to me that it is not a case of dilution per se, but a highly complex distributional issue. In this viewpoint, as I understand it, credit undermines the government currency, chiefly by gaining seigniorage. However since they have no reliable way to destroy the currency (ie taxes) it can also lead to monetary instability.

Empirically this viewpoint would explain a lot of issues: Bank runs and the need for a deposit guarantee. Boom and bust cycle being heavily associated with credit increases and decreases. And most importantly in my mind, the huge profits banks and other financial institutions are making, while their social value is often hard to ascertain. The bonuses of CEO’s of “normal”banks often far outstrips that of the most profitable businesses in non-financial sectors. There doesn’t seem to be a good reason why. Yes they bear huge responsibilities, but so does an underground operator. Economic value has nothing to do with responsibilities but demand. However scientific studies investigating the relative competence of CEO’s of financial institutions show very little differentiation; it matters very little for the profit whether you have a good CEO or a merely average one.

“We have a service economy and flexible high response manufacturing systems. Credit is more likely to induce instant or near instant expanded output than it ever has in the history of man.”

You argue that the modern service economy necessitates financial intermediation. I agree. However it is not clear credit is actually needed for financial intermediation. The recent gains in financial intermediation have little to do

To put it another way. The point of money is to serve as a storage of value. If we assume an economy at full demand, then someone needs to defer consumption to allow you to use that credit. However in the current system that doesn’t happen. The bank doesn’t defer consumption, nor do her shareholders, or depositors (since credit creation is not liquidity constrained), so this would lead to inflation. (or atleast a redistribution of wealth) In this view the huge profits that banks are making are a result of market distortion not financial competence. Note also the preferred position banks have being able to take loans at the Fed for near zero interest rates.

Then again I might be wrong. I need to think a little more about it before I can make an informed judgement on the issue.

Regards

Lee Wang

“It circulates and eventually reaches a bottleneck.”

Does it. Or does it get absorbed into excess savings of the non-government sector, or taxed out of existence?

When you have millions of people out of work it is very difficult to argue that there is a ‘bottleneck’ on the supply side.

Regarding common stock. I see three problems, first the lack of sound information on business dynamics for most citizens, Lee Wang

Private ratings agencies could keep up with such things.

secondly the lack of division of management and labour. Lee Wang

That’s not a bad thing. Japan has a “promote from the factory floor” philosophy and it has worked well for them.

Sometimes it may be economically most efficient to employ more workers, this surely would have a downward pressure on the existing salaries of workers who are incentivized to vote against an expansion of the labour force. Lee Wang

OTOH, since they are share holders, they are incentiveized to vote in the interest of the company since they are part owners of it.

Third common stock seems to undermine the government monopoly on the currency. Lee Wang

Fiat is the ONLY means to extinguish tax liabilities. That is quite enough backing.

Again regarding other countries using U.S. currency, would you agree they are effectively materially supporting the American state and undermining their own? Lee Wang

Yes, they are. OTOH, they are “buying” a historically well managed currency, at least compared to other nations.

When you have millions of people out of work it is very difficult to argue that there is a ‘bottleneck’ on the supply side. Neil Wilson

I am for a universal bailout of the entire population, including non-debtors, with new fiat till ALL credit debt is paid off. Think that might help aggregate demand? And without increasing debt? And no, new fiat spent into existence without borrowing is not “debt” in any meaningful way.

Credit is more likely to induce instant or near instant expanded output than it ever has in the history of man. Neil Wilson

Then let the individual businesses extend credit in THEIR OWN goods and services, not everyone elses like the banks do. That would be honest. Or at least remove ALL government privileges for the banks so their ability to extend credit is not artificially enhanced by government.

If I go to the barbers and have my hair cut paying with a credit card, then the expansion in output is instant and as a direct result of my credit use. Neil Wilson

I go to the same barber with my hard earned savings and now I have to wait till he/she finishes with you! My savings have been diluted!

That output *would not have happened* had I not used credit and would have been lost forever. Neil Wilson

Or the barber would have realized his prices were too high and lowered them EXCEPT maybe that is futile because he can’t lower his debt to the bank! And why is the barber in debt to the bank? Because if he didn’t borrow then he might never be able to save enough to open his own business because of negative real interest rates caused by his competitors’ use of bank credit.

Come on. Banking stinks. You must know that. Why defend it? Can’t the private sector ethically create money or credit?

Because we all know private rating agencies properly evaluate the market. 😀

Joking aside, there is one major issue we disagree on. To me it appears that it is in the public interest that the government keeps its currency monopoly as as such to ward all means of exchange (bonds, foreign currencies, credit etc) other than its own from the economic sphere.

You name taxing as backing, while true it is only a tool. Let me elaborate Taxing has three functions:

1. To place deincentives on bad behaviour. Ie: smoking, pollution, wealth disparity

2. To control aggregate demand

3. To create demand for the government currency, in the long run.

Those last words are important. If the government would stop taxing tomorrow, its spending power isn’t immediately reduced(it would lead to an explosion of aggregate demand though). If not otherwise incentivized citizens would gradually use other means of exchange, but only in the long run would it hurt the government. Taxing is a tool to keep the currency in circulation, but it doesn’t directly fuel it. The government could alternatively outlaw other means of exchange and force her citizens to use the currency by force. (taxes do this indirectly)

Any form of currency that is not directly tied to the government currency undermines the government monopoly and produces huge market distortions.

Regards

Lee Wang

Any form of currency that is not directly tied to the government currency undermines the government monopoly Lee Wang

Taxes could only be paid with fiat so that monopoly would remain absolute.

and produces huge market distortions. Lee Wang

I disagree. Coexisting government and private money supplies would insulate the government from private sector money mismanagement (e.g. the banking crisis) and vice versa (e.g. the “stealth inflation tax”). They would PREVENT market distortions primarily because government is force and the private sector should be voluntary cooperation.

Does it. Or does it get absorbed into excess savings of the non-government sector, or taxed out of existence?

Yes some goes to excess savings. In countries that run deficits all money taxed is then spent (redistributed).

The barber uses his money to buy goods. He might buy petrol for his car for example. If there is a supply bottleneck in oil, i.e. supply fails to meet demand, prices rise. This leads to price rises across the economy, and eventually the barber puts up the price of a haircut. The credit which paid for the original haircut added to that demand which, when it hit that oil supply bottleneck, helped to push up the price level.

Lee Wang et al: However since they have no reliable way to destroy the currency (ie taxes) it can also lead to monetary instability. The reliable way to destroy the currency ( bank credit money, not currency = government money is meant here), is the repayment of the credit. For you, the original barbershop customer, your credit card payment for the haircut. For the receiver of the funds, the barber, the gas station he paid with credit etc, it might be the use of these funds -liabilities owed BY the banking sector – to pay his credit card bill, liabilities owed TO the banking sector. Rather than circulating indefinitely until it hits an inflationary bottleneck, if things work well, it will hit one of these debts to a bank & be destroyed, or be saved. But the real immediate problem right now everywhere is the constraint on production due to insufficient money of any useful type, government money or bank credit money, not inflationary bottlenecks. This, the money destruction / redemption / leakage system, is working too well, is too reliable.

The two basic means of money creation “efflux” are government spending & bank loans, while the two basic means of of destruction “reflux” are taxation & loan repayment. The money the government creates is “better” money of course. Bank money is money because the government backs it.

One way of thinking of things is to glom together the gubmint & the banking sector. So you are getting all your lending directly from the gubmint (which is really what it works out to anyway; the banks are just intermediaries who take a vig). Then you can think of the loan repayment as a kind of taxation. Banks today are just mayors of the palace who are largely succeeding in usurping the sovereign’s power, to become the government.

If we assume an economy at full demand, We all wish (the non-bankster billyblogians). Not been seen in the USA since the 40s, or the late 60s if you are generous.

then someone needs to defer consumption to allow you to use that credit. However in the current system that doesn’t happen.

It, the consumption deferral, happens when people need to pay their debts or their taxes. In the current system, as it operates now, rather than not happening, it happens too much – it is THE problem nowadays, not the opposite problem of inflation, bottlenecks etc. The power of the money destruction / reflux system ain’t fundamentally broke, so it doesn’t need essential fixes. The money creation system IS broken – in particular, hardly anywhere is the minimal sanity represented by an effective JG, full employment present.

My apologies to all if I belabor the obvious.

(which is really what it works out to anyway; the banks are just intermediaries who take a vig). some guy

Wrong. “Loans create deposits (and liabilities).” Government created money (fiat) serves as reserves to net out liabilities between banks. And inter-bank lending greatly reduces even the need for those reserves since banks can normally “borrow back” the liabilities they create by making loans.

So banks can create many times the amount of fiat in existence.

F Beard: I was “glomming together” – thinking of the government plus banks as one entity, intentionally making no distinction between government money & bank money, thus thinking only of horizontal money (just looked it up, can never tell my left from my right, or vertical from horizontal 🙂 ), or only vertical money, or equating the two. Of course most money is bank money, not government “fiat” money, nowadays. The “fiat money” reserves – debts owed by the core government to the banks – are then what one pocket owes to another pocket of the same entity – not too meaningful. It’s the same as if the only bank were the government, the only money its “fiat” money, which it lends out/issues & redeems/taxes/gets repaid. Then you can think of the banks(ters) as government employees who take a cut of the money they are playing with, that’s all. Like employees of the Bureau of Engraving & Printing who are allowed to take out some money from the presses and invest it, as long as they promise to put it back (bank regulation) with a bit of interest. They may have capital constraints (they’re constrained to peculate in proportion to how much they stole already 🙂 ) Forget that paragraph if you don’t like it, it’s an aside, just a way I like to think of things sometimes.

“I go to the same barber with my hard earned savings and now I have to wait till he/she finishes with you! My savings have been diluted!”

An assumption there that there is a queue, always a queue, and no spare capacity. How many millions unemployed again?

“Or the barber would have realized his prices were too high and lowered them”

Nobody ever does that in real life. Prices are sticky and always will be. People need to earn enough to live.

“Come on. Banking stinks.”

No it doesn’t. That is as much a religious belief as deficit mania. The current version of banking stinks and it needs to be rectified.

Distributed lending is responsive to the needs of entrepreneurs as long as it is limited to Schumpterian investments and with a stable over time private debt to GDP ratio.

On the other hand centralised lending requires the Wisdom of Solomon, and we already tried that with the quantity Monetarist experiments of the early 1980s. It doesn’t work.

The ‘positive money’ people always strike me as closet monetarists who still believe that we shouldn’t have abandoned Friedmanism in the 1980s. They see this crisis as a way of putting their religious icon back on the top of the hill.

There is nothing wrong with bank lending. It’s a good system if properly controlled – much as a nuclear power station is a good system if properly controlled.

F. Beard

These posts are arduous and indirect. Is there any way we can communicate directly?

Prices are sticky and always will be. People need to earn enough to live. Neil Wilson

Because debt is sticky. Your “solution” – “credit” – is the cause of the problem!

Not that I am for falling prices; I am for ethical money creation which bank credit isn’t.

On the other hand centralised lending requires the Wisdom of Solomon, and we already tried that with the quantity Monetarist experiments of the early 1980s. It doesn’t work. Neil Wilson

And that has to do with what? I have NEVER advocated centralized lending. I advocate DECENTRALIZED private money creation.

How many millions unemployed again? Neil Wilson

Again, your “solution” is the cause. People’s jobs have been automated away with their own stolen purchasing power via credit creation for the so-called “credit-worthy.”

Nor am I against automation but it should be ethically financed.

No it doesn’t. That is as much a religious belief as deficit mania. Neil Wilson

It’s based on the belief that private money creation, like all other business, should be ETHICAL. Instead, the so-called “credit-worthy” are allowed (via numerous government privileges) to steal the entire population’s purchasing power – supposedly for the good of all. How’s that working lately?

But if you want truly private, decentralized credit creation then why the heck should the government backstop the banks with deposit insurance, a lender of last resort, sovereign debt, and legal tender laws for private debt?

“But if you want truly private, decentralized credit creation then why the heck should the government backstop the banks with deposit insurance, a lender of last resort, sovereign debt, and legal tender laws for private debt?”

It can never be truly private. Leaping from one extreme to another doesn’t advance the argument.

It can never be truly private. Neil Wilson

Why not? Monetarily sovereign governments certainly do not need need banks as MMT has pointed out; monetarily sovereign governments can simply spend their fiat into existence and tax SOME of it out of existence as needed to prevent price inflation.

And as for the private sector, why should some, the so-called “creditworthy” and the banks be allowed to steal the purchasing power of everyone else? Especially when common stock as a private money form allows the necessary consolidation of capital for economies of scale but in an ethical manner?

“And as for the private sector, why should some, the so-called “creditworthy” and the banks be allowed to steal the purchasing power of everyone else? Especially when common stock as a private money form allows the necessary consolidation of capital for economies of scale but in an ethical manner?”

Yes so you keep saying. That unfortunately doesn’t make it so.

That unfortunately doesn’t make it so. Neil Wilson

Negative real interest rates in housing is all the proof needed. Some cheaper consumer goods are not enough to compensate for that stolen purchasing power.

Come on, the game’s up. Credit creation is a sneaky way for the rich to exploit the poor. And to the extent it is privileged by government, it is fascist. And besides that, lending money into existence creates an unstable, dangerous and most likely non-optimal economy.

Would have have defended slavery, I wonder?

Pardon that last crack, please.

I notice I stuttered too.

Sorry.