Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – August 23, 2014 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

A nation can run a government sector surplus, which is larger as a proportion to GDP than the external deficit, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

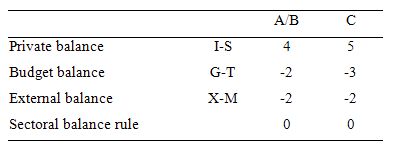

The following Table represents two options in percent of GDP terms. To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

The first set of possibilities (A/B) show that the external deficit is exactly offset by the government sector surplus and under those circumstances the domestic sector is spending less than they are earn (that is, net saving (overall) is negative).

You can see that the private sector balance is positive (that is, the sector is spending more than they are earning – Investment is greater than Saving – and has to be equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

Option C – the scenario in the question – shows that the nation is running an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) but the government sector surplus is larger (3 per cent of GDP). Under these circumstances, the private domestic deficit rises to 5 per cent of GDP to satisfy the accounting rule that the balances sum to zero.

So what is the economic rationale for this result?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real costs and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 2:

The automatic stabilisers built into national government fiscal policy always operate in a counter-cyclical manner.

The answer is True.

The automatic stabilisers do always operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is slowing they provide stimulus that would otherwise not be there. The declining tax revenue and rising welfare payments force the fiscal balance into a more expansionary phase (even if discretionary government policy is unchanged).

The automatic stabilisers push the fiscal balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit when GDP growth declines and vice versa when GDP growth increases. These movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

We also measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the fiscal balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

This decomposition provides (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical fiscal balances. The fiscal components are adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal balance is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal balance into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

In some of the blogs listed below I go into the measurement issues involved in this decomposition in more detail. However for this question it these issues are less important to discuss.

The point is that structural fiscal balance has to be sufficient to ensure there is full employment. The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose.

In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

Given the non-government sector will typically desire to net save (accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue) over the course of a business cycle this means that there will be, on average, a spending gap over the course of the same cycle that can only be filled by the national government. There is no escaping that.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap. However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a fiscal surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the fiscal outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs). But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The fiscal balance will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment – which I define as 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

So while the automatic stabilisers act to provide some floor in the collapse in aggregate demand they may still leave a structural deficit that is insufficient to finance the saving desire of the non-government sector at an output level consistent with full utilisation of resources.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 3:

Sovereign government spending becomes more costly when the bond markets push yields on new public bond issues up.

The answer is False.

For a sovereign government that issues its own currency there is no binding revenue constraint on government spending. The interest servicing payments come from the same source as all government spending – its infinite (minus one cent!) capacity to issue fiat currency. There is no “cost” – in real terms to the government doing this.

The concept of more or less expensive is therefore inapplicable to government spending.

The cost of government spending is the real resources that are deployed in the production of the goods and services being purchased rather than the fiscal entry in the Treasury books.

Rising bond yields do not measure these opportunity costs.

In macroeconomics, we summarise the plethora of public debt instruments with the concept of a bond. The standard bond has a face value – say $A1000 and a coupon rate – say 5 per cent and a maturity – say 10 years. This means that the bond holder will will get $50 dollar per annum (interest) for 10 years and when the maturity is reached they would get $1000 back.

Bonds are issued by government into the primary market, which is simply the institutional machinery via which the government sells debt to “raise funds”. In a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates it is clear the government does not have to finance its spending so the the institutional machinery is voluntary and reflects the prevailing neo-liberal ideology – which emphasises a fear of fiscal excesses rather than any intrinsic need.

Once bonds are issued they are traded in the secondary market between interested parties. Clearly secondary market trading has no impact at all on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders. In the context of public debt issuance – the transactions in the primary market are vertical (net financial assets are created or destroyed) and the secondary market transactions are all horizontal (no new financial assets are created). Please read my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

Further, most primary market issuance is now done via auction. Accordingly, the government would determine the maturity of the bond (how long the bond would exist for), the coupon rate (the interest return on the bond) and the volume (how many bonds) being specified.

The issue would then be put out for tender and the market then would determine the final price of the bonds issued. Imagine a $1000 bond had a coupon of 5 per cent, meaning that you would get $50 dollar per annum until the bond matured at which time you would get $1000 back.

Imagine that the market wanted a yield of 6 per cent to accommodate risk expectations (inflation or something else). So for them the bond is unattractive and they would avoid it under the tap system. But under the tender or auction system they would put in a purchase bid lower than the $1000 to ensure they get the 6 per cent return they sought.

The mathematical formulae to compute the desired (lower) price is quite tricky and you can look it up in a finance book.

The general rule for fixed-income bonds is that when the prices rise, the yield falls and vice versa. Thus, the price of a bond can change in the market place according to interest rate fluctuations.

When interest rates rise, the price of previously issued bonds fall because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering a higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increase, becoming more attractive as newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

Further, rising yields may indicate a rising sense of risk (mostly from future inflation although sovereign credit ratings will influence this). But they may also indicated a recovering economy where people are more confidence investing in commercial paper (for higher returns) and so they demand less of the “risk free” government paper.

So you see how an event (yield rises) that signifies growing confidence in the real economy is reinterpreted (and trumpeted) by the conservatives to signal something bad (crowding out). In this case, the reason long-term yields would be rising is because investors were diversifying their portfolios and moving back into private financial assets.

The yield reflects the last auction bid in the bond issue. So if diversification is occurring reflecting confidence and the demand for public debt weakens and yields rise this has nothing at all to do with a declining pool of funds being soaked up by the binging government!

But all of that has nothing to do with the real resource costs embodied in goods and services that governments purchase.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

With respect to question number 2. In some places (Canada as an example) there is employment insurance (EI) and then there is welfare which can be applied for after a relatively short period when EI ends. While EI is federally funded welfare is funded 80% by the provinces and 20% by the municipality in which the applicant lives. Neither source creates the currency issued so it must all come from taxes. Can this form of welfare still be considered part of the automatic stabilization (especially in the case of more prolonged downturns)?

I should add to my comment above, that workers ‘contribute’ to EI through payroll deduction when they are working even though it is a federal program.